Sabah namazını Hələf özündə.

Günorta namazını Qarsın düzündə.

Axşam namazını yar Tiflisində.

Mövlam qanad verdi uçdum da gəldim.

Morning Prayer in the heart of Aleppo

Midday Prayer in the plains of Kars

Evening Prayer in beloved Tbilisi

My Master gave me wings, I flew, and I came.

The music and poetry of ashiq bards extend across a wide geography which cannot be confined to the borders of modern nation states. The above stanza from the dastan epic “Aşıq Qərib” demonstrates the inherently translocal nature of this tradition. The protagonist, after being estranged from his lover for seven years, miraculously travels, with the help of the Prophet Khidr, from Aleppo to Kars and on to his lover’s home in Tbilisi—three cities today situated in three different countries, Syria, Turkey, and Georgia. Ashiqs, in both their literary imagination and in actual practice, have long traversed this geography. Historically, these singer-poets filled the role of both entertainers and bearers of news travelling far and wide, often performing for different audiences in multiple languages. Even in recent history, during the period of hard political borders between Turkey, the Soviet Union, and Iran, the sounds of these bards crossed frontiers on radio waves and cassette tapes.

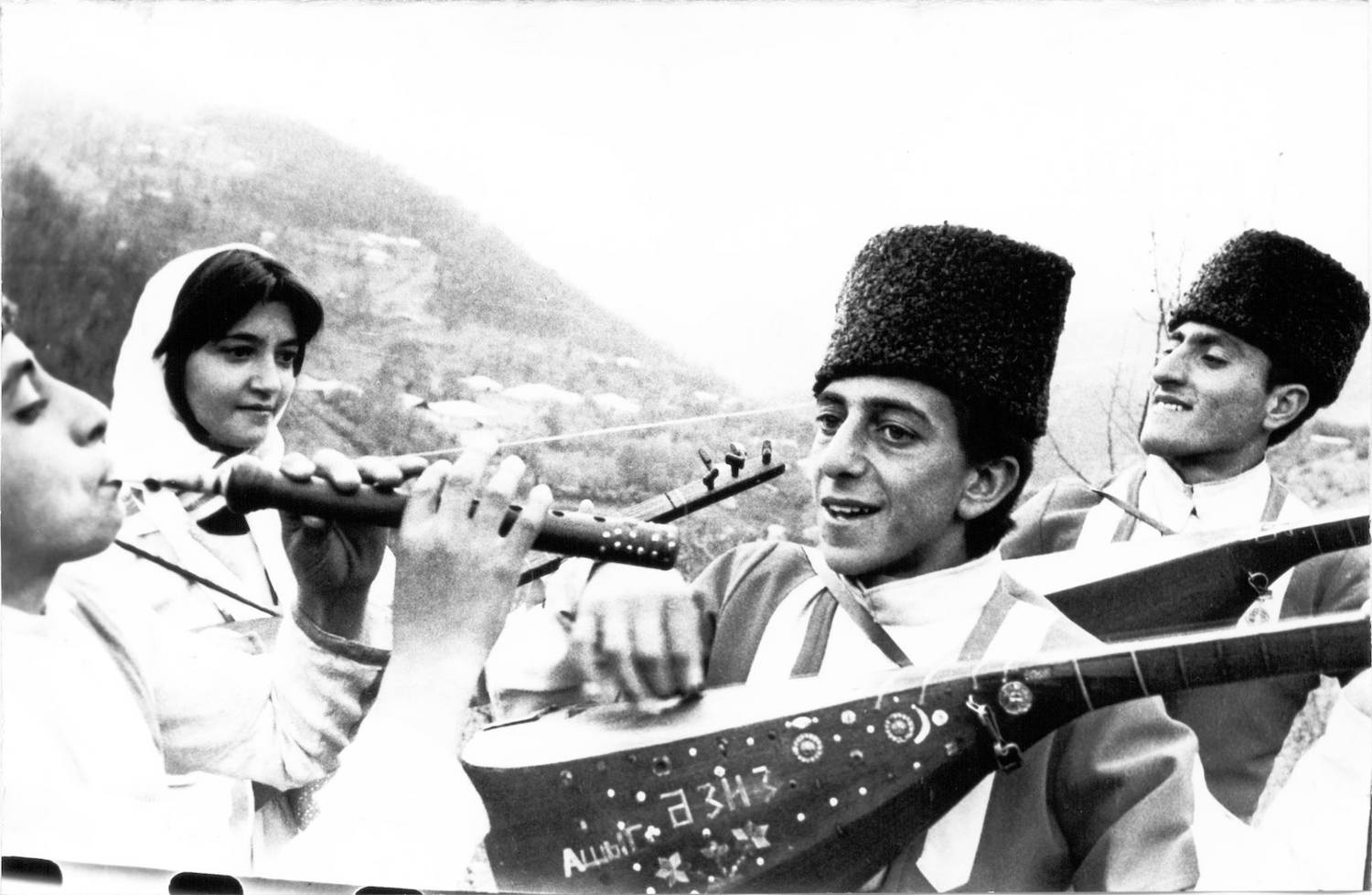

The tradition of poet-bards spreads from the eastern edges of Central Asia to the Balkans and is not limited by ethnicity, language, or religion. The Caucasus, Anatolia, and Northwest Iran have long been an important centre for the development of bardic poetry and music. The Turkic name for bards in this area, ashiq, and its cognate ashough in Armenian or ashoughi in Georgian, comes from the Arabic word عاشق, meaning lover or enamoured. Some say that the bard as lover refers to the idea that the musician must be inspired to write poetry and perform music. In some cases, this inspiration is said to have a metaphysical or divine origin, with some bards claiming to receive the skills and title of ashiq in their dreams. More commonly, the tradition is passed down generationally with new musicians learning from a young age in a family setting or through an apprenticeship similar to master-pupil relationships in other musical cultures. Throughout this region ashiqs are typically solo performers, accompanying themselves on the long-necked stringed instrument made of mulberry wood called the saz, chongur, or qopuz, although some ashiqs may use bowed instruments and, in other areas, ensembles are also popular.

In the past, teahouses and weddings served as the main performance venues for these musicians. In urban centres like Tabriz in Iran and Kars in Turkey, the teahouses close to the bus terminals and bazaars were well known as venues for ashiq performances, as villagers coming to these towns could stop off to listen to the ashiqs before returning home. These performances to this day are fairly informal affairs with people giving the musician tips for special requests; the ashiq will walk between the tables and chairs stopping to sing before friends, special guests, or for those making requests. Performances at weddings, though seasonal, are much more lucrative for musicians particularly since the disappearance of traditional teahouses. During the Soviet period, ashiq performance became more formalized and institutionalized across the Caucasus with concerts being staged at theatres and recorded on TV and radio. The new political context not only led to changes in musical aesthetics but also to an increased number of female ashiqs as performance spaces became less segregated.

kalbajar.com

Although instrumental virtuosity is important amongst ashiqs, knowledge of poetry is what really matters. Traditionally, ashiqs were judged on their ability to remember poetry and their charisma in interpreting epic stories, known as dastan or hikâye. These epic poems were mostly transmitted orally and have countless variations across geography and language. In the past these epic tales were performed over several days with the ashiq interpreting a section each day at a teahouse or wedding. The recitation of a full dastan combines several different elements—spoken narration, including interpreting and providing historical context, and the singing of poetry accompanied by the saz. The themes of dastans vary. Some are heroic adventure stories, such as that of the Koroğlu warrior of superhuman strength who defended the poor against the rich and powerful. Others, like Ashiq Qerib, tells the stories of ill-fated lovers. Dastans originating in the ashiq repertoire have provided inspiration beyond the tradition. In 1837, Lermontov collected and published the story of Ashiq Qerib which was later adopted into a film by Parajanov in 1988. Today it is rare to hear performances of whole dastans by ashiqs. Instead, short well-known verses or melodies from a dastan are performed independently together with other relatively shorter melodic pieces known by the more generic name hava and which tend to be about unrequited love or the beauty of nature.

Another entertaining performance genre amongst ashiqs is the song duel, known as karşılaşma, “to encounter,” in Turkey or deyişmə in the Caucasus and Iran. This involves two or more ashiqs facing each other in an event in which they have to improvise poetry. According to Yildiray Erdener, an academic who studied the song duels of ashiqs in the eastern Turkish town of Kars in the 1980s, the length of a song duel depends on the mood of the competing bards. It can have from five to seven sections and, traditionally, one of the final sections will always include personal attacks and insults. In each section, the bards sing their improvised verse to a different tune. Since a song duel is a social event, other aspects of the performance—such as spontaneity, competition, interaction, and the sharing of traditional knowledge through music and poetry—are sometimes more important than the poetic content or the number of syllables in a line. Bards often entertain the audience with a further challenge called “lab değmez” or “dudak değmez”, literally “lips don't touch.” Here, they must improvise poetry but omit five consonants (b, f, m, p, and v) which cannot be pronounced without closing the lips. Before the performance begins, each of the competing bards places a pin in his mouth so that if he inadvertently uses one of the prohibited letters, the pin will prick him as his lips close.

In some contexts, the role of the ashiq is more of a teacher or wise figure than an entertainer. The boundaries between the secular and sacred are often blurred in ashiq music as mystical, moral, and religious themes are commonly adopted. This is particularly the case amongst Alevi ashiqs in Anatolia. As a religious tradition and belief system with no central texts, Alevism has relied heavily on the oral transmission of knowledge through the poetry of ashiqs. In the cem ceremony, the central Alevi ritual, the ashiq recites a range of poetry which touches upon moral issues, accounts of early Islamic figures and events, and themes of mystical love. With the growth of the recording industry in Turkey, many of these songs have left the ritual context of the cem and gained widespread popularity. While ashiqs in Iran still often begin performances with invocations to God, the Prophet Muhammad, and his Family, these more overtly religious references have faded in the Caucasus.

Union of Ashiqs of Azerbaijan / Azərbaycan Aşıqlar Birliyinin

Over the last century as the tradition of ashiqs has become increasingly “nationalized,” it has seen a corresponding decline in popularity, particularly in some areas and amongst certain ethno-linguistic groups. Since 2009 “Art of Azerbaijani Ashiq” has been inscribed in UNESCO’s “List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity” under the Republic of Azerbaijan, despite its transnational and multi-ethnic nature. Whilst several initiatives have aimed to promote the “national” tradition within that Republic, the art form in other areas, such as Georgia or Iran, receives little or no state-support and performance contexts are extremely limited. Over the last ten years, professional musicians from other countries have had to travel between Turkey and Azerbaijan to make a living, performing at festivals across these countries. Despite the decline of radio and state-supported recording industry, the two main sources of distribution during the 20th century, new media and online platforms, allow recordings of these musicians to circulate across a large region—between Kars, Tabriz, Baku, and Tbilisi.

These contemporary videos can be found alongside hours of archival footage on YouTube as well as several features including this documentary by Armin Ardi on the Assyrian Ashiq Yusuf Ohanes from Urmia in Iran and this short film by Kiarim Gumbatov about Ashiq Ziaddin from Georgia.

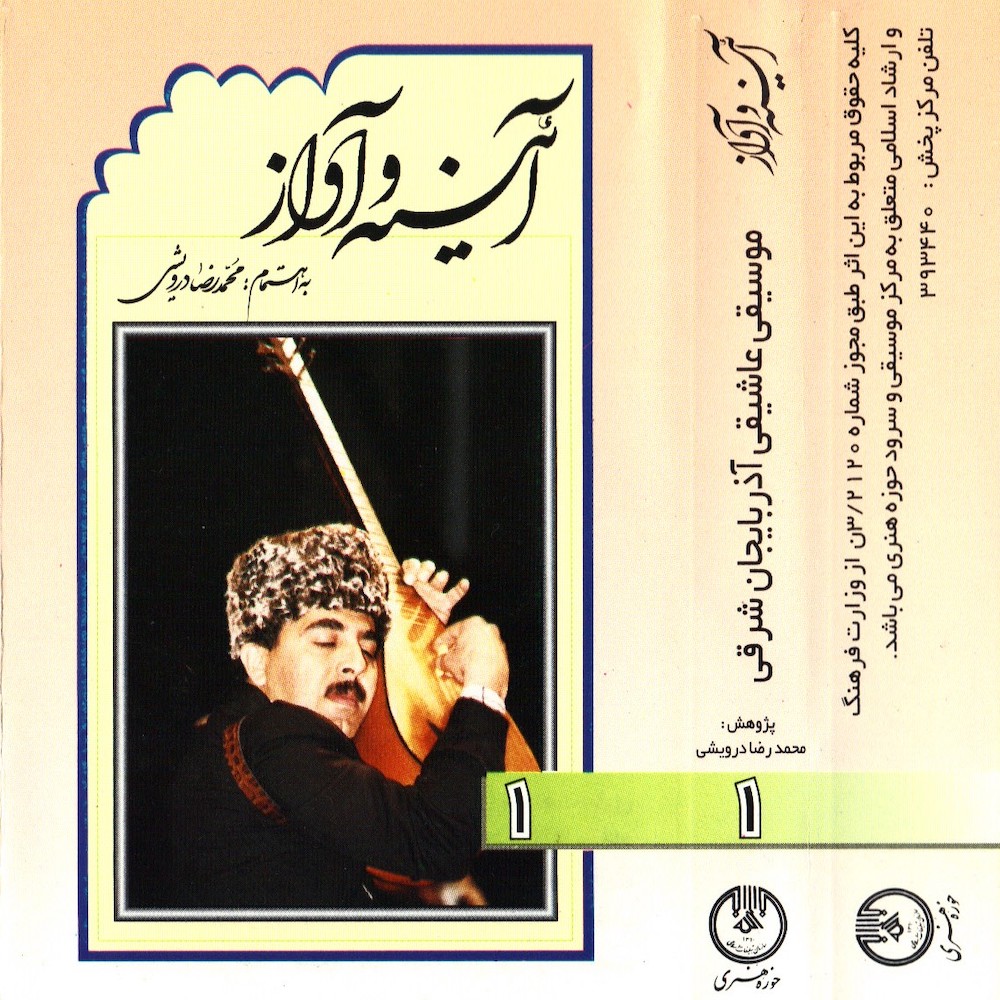

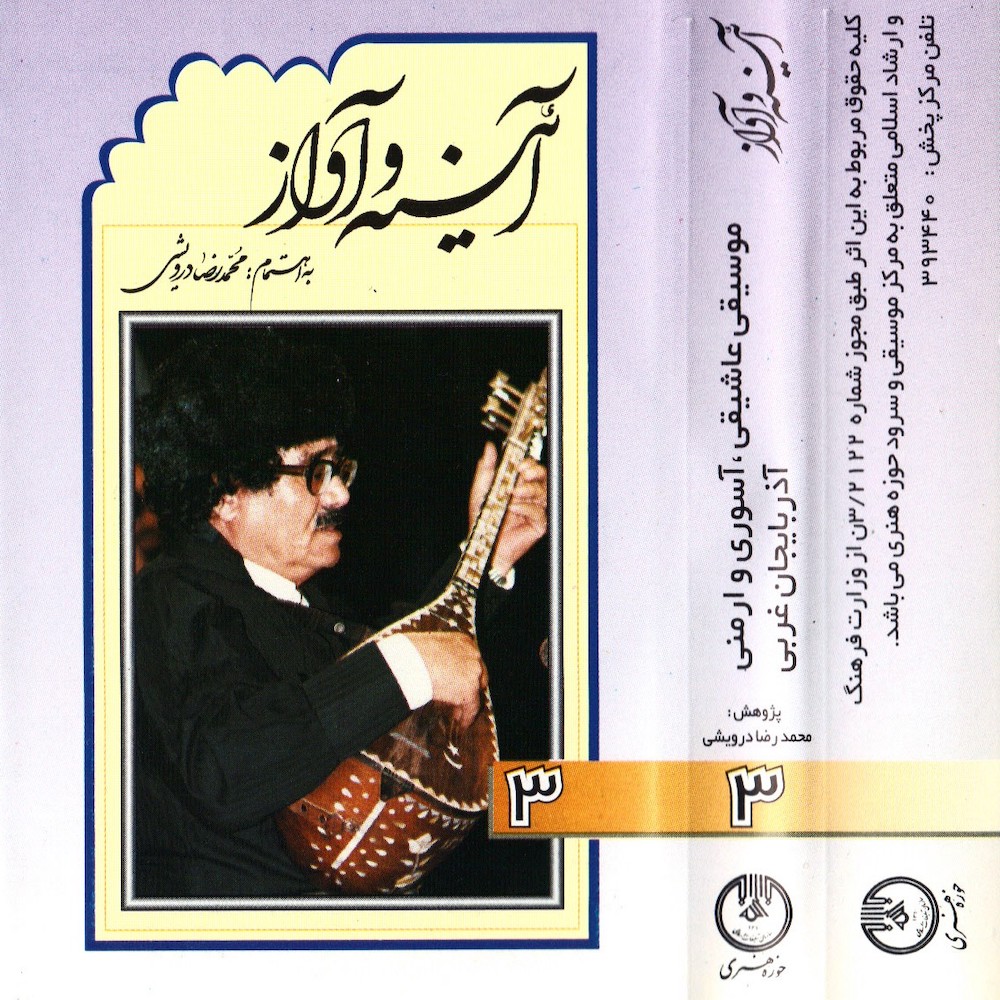

Cover. Cassette № 1 of Mirror and Songs Collection: "Ashiq Music of Eastern Azerbaijan," recorded in 1994 Cover. Cassette № 3 of Mirror and Songs Collection: "Ashiqi, Asuri & Armeni Music of Western Azerbaijan," recorded in 1994 Cover. Cassette №4 of Mirror and Songs Collection: "Ashiqi and other Music of Western Azerbaijan," recorded in 1994

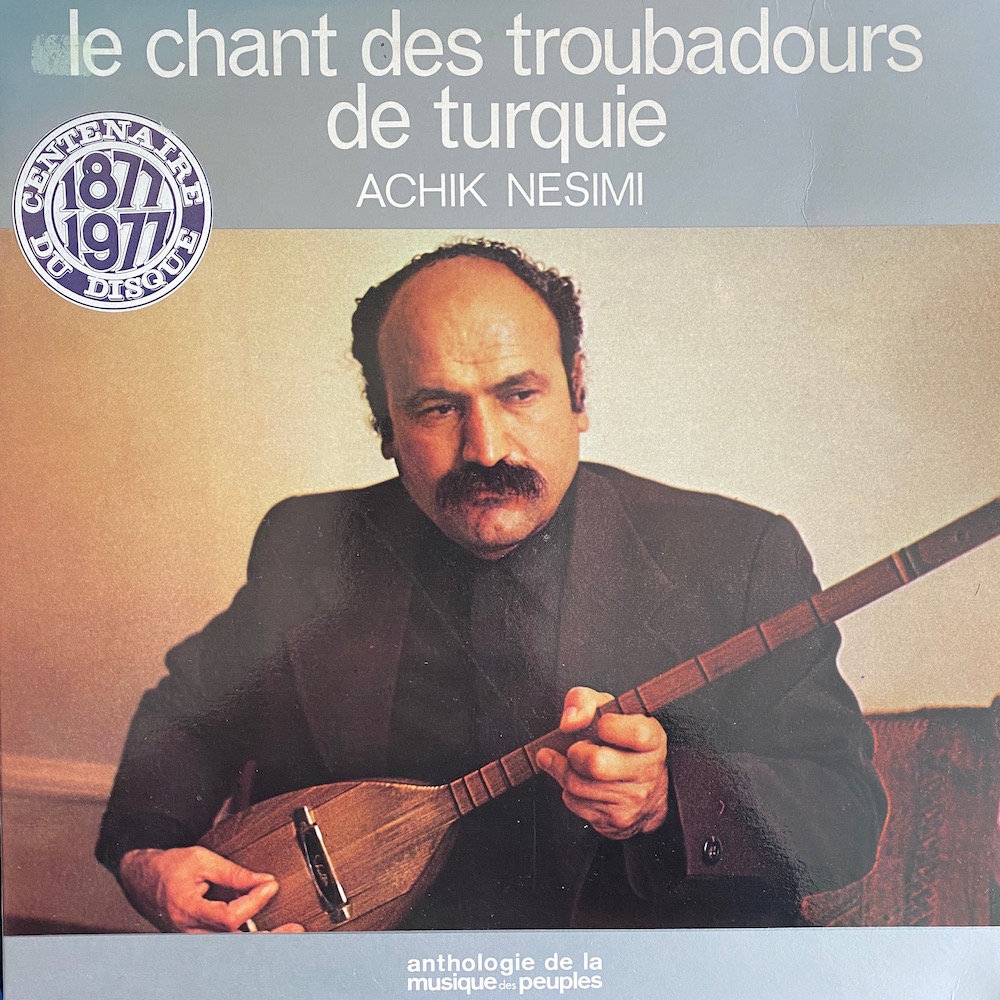

Cover. Nesimi Çimen. Anthology Le chant des Troubadours de Turquie, 1979

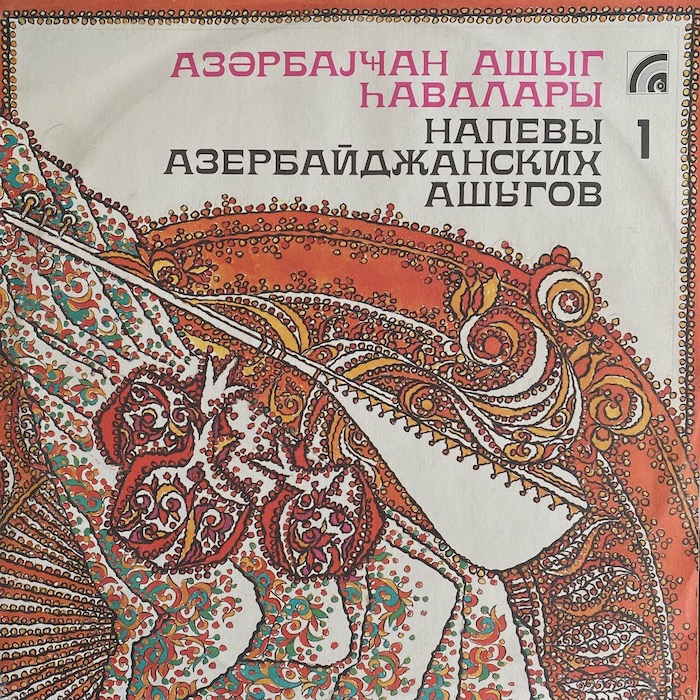

Cover. Various. Melodies of the Azerbaijan Ashiqs, 1993

Back Side. Various. Melodies of the Azerbaijan Ashiqs, 1993