For three years, photographer and anthropologist Makar Tereshin has been traveling to the Arkhangelsk region and documenting the life of those who hunt for space metal debris around the area of the Plesetsk Cosmodrome. We are publishing Makar’s short story about the unexpected consequences of space exploration, as well as his photographs from the expeditions followed by fragments of conversations with local residents.

Seven years ago, due to my interest in the temple architecture of the Russian North, I traveled around the Arkhangelsk region. It was while visiting the villages along the Onega river that I first heard about the Plesetsk Cosmodrome—my interlocutors complained about the space vehicle launches and connected them with the deterioration of the health of local people. However, according to them, in other villages in the region’s northeast which were in the fallout zones of the first stages of step rocketsstep rocketsSuch rockets usually have several sets of staging, each of then equipped with its own engine. As soon as the fuel in the engine is exhausted, the staging is jettisoned and falls down under the influence of gravity. launched from Plesetsk, people faced even more spaceport-related concerns. This is how I first heard about the Mezensky District, where the debris of step rockets serve as a reminder of the earth's periphery to space infrastructure and the ways in which it directly impacts the lives of people affected by the process of space exploration.

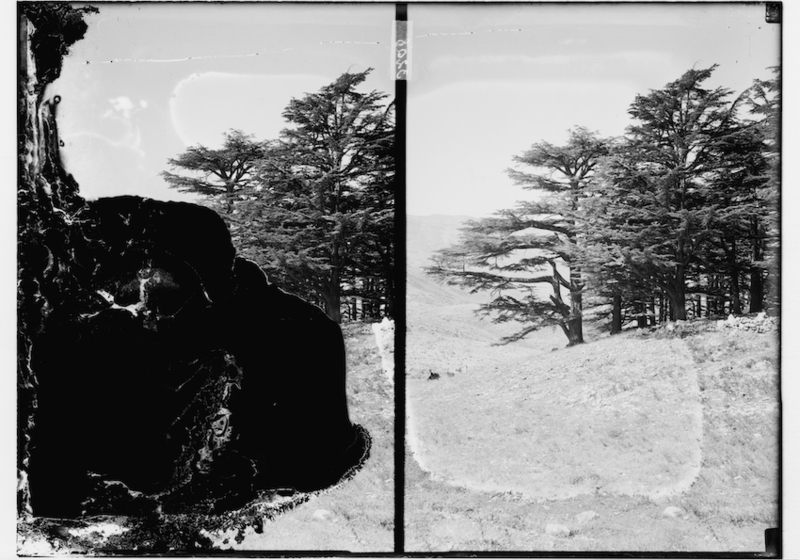

A couple of years later, on an early morning in January, I stood in a snow-covered pine forest bordering a swamp stretching between two rivers in the Mezen basin. Below, there was a large cone-shaped barrel—a “Soyuz” rocket stage, which my companion and I were slowly cleaning the snow from. When we finished, Nikolay opened the rocket body with a chainsaw and showed me the stamp on one of the engine parts, explaining that the stage had been there since 1989—it was then that the Mezen village dwellers became more frequent visitors to the fallout zonesfallout zonesFallout fields are part of the ground-based space infrastructure, a place where separating parts of launch vehicles land. for the purpose of collecting rocket stages . Working at the cosmodrome or forming their own brigades, experienced entrepreneurs began space metal hunting to partly provide for their families by submitting them for recycling or to use the material themselves: for example, for the manufacturing of boats, furnaces, and grave fences.

Pyotr Evgenievich, 67 years old, an interview fragment (2018):

I wanted to explain why I had actually headed off. We filed an application, the first rocket was found in a swamp, where the fuel was already draining into the river. Somehow, we finished with all the formalities and applied to the village council from there, and then—to the district administration, the administration contacted Plesetsk, informing them that the rockets were really very close. We found it about thirty seven kilometers [from the village] and it was draining straight into the river. The military provided a helicopter. We showed exactly where it was, the spot where it was lying. We flew over the area and saw that there were lots of rockets. D. showed no interest in it, but I did. The next winter I had already headed off to look for them on my own. I left for three or four days. There were cases when they lost me, well, different things happened. I got out on autopilot, found myself drowning in a swamp, and came across bears. Well, it was good that I had dogs there with me, so it ended up well, I came out alive . . . I was already familiar with those places and used a map and a compass for navigation. GPS was not available then, there was nothing. A map, a compass—and that’s it. And the sun. Here I am, alone, the numbers were not impressive . . . I was hunting for contacts then. They bought radio parts at the stalls.

Tracing the trajectories of rocket stages and the local residents’ sudden encounters with them, I focused on the experience of hunters whose lands overlapped with fallout zones. Faced with a radical transformation of life and uncertainty during the years of the (post) Soviet crisis, they began to develop new territories for procurement of rocket stages . At the same time, brigades had to establish new orders for their extraction and form networks of interactions in a landscape that was just beginning to become familiar to them. Long weeks spent in the taiga allowed them to study rocket “behavior”—the trajectories of their fall and the places where they could look for new rocket stages after the next launch. The construction of wilderness huts and ice roads, as well as the preparation of new lands for the procurement of missiles, made settling in these territories possible.

Sergey Gennadievich, 57 years old, an interview fragment (2018):

— If you drive up, and it [the rocket] is already prepared, sawed into pieces ready to be taken away, do not try to saw it. If you find “reserved” written on the rocket, you should not saw it, either.

— Why?

— Because it’s not a good idea. The place is not busy, we will still find one another. Once there was an incident: we prepared a stage and were planning to get back by an ATV to pick and pull it away . . . But as soon as we arrived, we found the back part left with nozzles and [someone else’s] saw left. All the rest was missing [stolen]. We took the saw and wrote our location on the iron, the place where our hut was situated. They did show up, we had a talk and reached a compromise . . .We took their weapons and cash, “When you load everything onto the car, you will get your weapons back.” And that's it, no scandals, and now we get on well with them. Well, if you see the stuff has been prepared by someone, why should you touch it?

Pyotr Veniaminovich, 63 years old, an interview fragment (2018):

So here you go, you bump into something and leave your mark—well, just cut something out there. So, if someone else sees it, they will know who it belongs to. Our foreman leaves his own mark. And you know at once if it belongs to Sergey or Misha. We have never touched other people’s stuff. You put a mark, mine says “PV” and that’s it. I do not touch theirs and they do not touch mine.

While working on this project, I found it important to problematize the extra/terrestrial material, environmental and technological connections that ensure the possibility of a human presence in space. Attention to step rocket stages allows us to see how the development of new frontiers beyond Earth links some people’s lives to ruined landscapes. Thus, the territorial distribution of space infrastructure in the Mezen Basin recontextualizes the “wild” spaces of the North as the most suitable places for reaching Earth’s orbit.

Ivan Fedorovich, 58 years old, an interview fragment (2019):

— How did you get there? How did you used to travel to the hut?

— On foot. It took me two weeks to reach it on foot. I brought some food along and walked for one week, as soon as I was starting to run out of food, I turned around and headed back. I also had a tent.

— And how long did it take you to reach the hut?

— The hut is thirty kilometers away, and I do ten hours of walking. I carry a load, it should not take long if you run, but [when carrying heavy stuff] you keep on walking anyway, still you have enough food. As you consume it, the load gets lighter and then, at a certain point, it's time to turn back. Sometimes you drop in somewhere, things might slow you down, you get interested in stuff. You might think of reaching out for a hut to find more food there. Or you can just eat berries. You get tired. It’s in summer when you look for stages. During one summer you might walk one thousand kilometers. The rocket falls, stages are discarded and land in the area of no more than four kilometers. They may fall at a two kilometer distance from one another. At a seventy meter distance you no longer see the rocket, at fifty meters you could still do, it’s impossible to pass it by at a seventy meter distance. If you find [a stage] within this square, look for three more. Here they [other hunters looking for stages] work, then they go broke and lose everything. If all can be easily carried away from the swamps, spotting things in the forest is a hard task! And, as for me, I always do my own calculations. What is more, they [stages] usually fall like a hare running. Almost like a principle. And also, I don’t know why, they are kind of attracted by the lowlands—if there is a stream and some sort of vortex, the flow pulls them in. So, you need to check all the lowlands first. If you spot one [stage], keep on searching. That's it, and carry it in mind that this thing flies from the height of thirty kilometers and somehow it still has its air flow, but the lowland pulls it in. Pretty interesting, isn’t it? And it does not do it on purpose, it’s uncontrollable. The lowlands attract it, that's for sure!

By addressing the fallout zones, I associate space exploration not only with popular images of modernity, extraterrestrial research, or human mobility, but also with consistent pollution, and political and ecological alienation. This allows the rethinking of the exploration of space and its attendant littering of ever larger spaces as an enterprise that extends human aspirations devastating life on Earth beyond our planet. Fallout zones blur the boundaries, revealing mundane interdependencies in space exploration that do not fit the ordinary planetary (both global and local) scales. While contaminating and destabilizing life in the radius of the space infrastructure, discarded rocket stages provide new opportunities to sustain the lives of those affected by space launches.

The project features photographs that I took during field work in the Mezen River Basin and Plesetsk Region in 2017-2020. Archival images and video documentation were provided by my interlocutors who worked in rocket stages procurement teams in the 2000s. I also used photographs from the hunter V. Lokachev’s private archive. My interlocutors’ names have been altered.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich