Photographed by Jacquie Manning

Cosmin Costinas and Inti Guerrero, the artistic directors of the 24th Biennale of Sydney, introduce their project Ten Thousand Suns, focused on the role of sound experiences, historical elements, and experimentation in the exhibition. As part of our collaboration, EastEast’s current Music Issue will highlight selected artworks and engage with artists featured in the Biennale.

“Ten Thousand Suns” conveys divergent images. The singular life-giving body that is the sun, like the world it shines light upon, has otherwise been known under thousands of different words in as many languages. Each name carries with it a different cultural viewpoint, many of which do not rely on a vision of a single sun. The image of many suns evokes projections of a scorching world, both in several cosmological visions and in our moment of climate emergency and of a world ablaze.

And yet the sun doesn’t stop shining. It doesn’t stop when empires wither and want to take down the light of day with them. It didn’t even stop in horror when places and continents were broken by these empires, invaded and settled. It did not stop when the HIV/AIDS pandemic was left to run through bodies, communities, and dreams. The suns shone on. They shed light below where broken pieces were being put together. Remembering what was forgotten, forbidden, and creating anew. Mourning and returning to life. In strength and exuberance. In carnivals of rays and radiance. In lineages of resistance and collective power. In Mardi Gras. Under ten thousand suns dancing gently like a morning; the joy of cultural multiplicities affirmed, and of carnivals as forms of resistance rallying against colonial oppression and dehumanization.

The 24th Biennale of Sydney worked within these different layers, acknowledging the deep crises derived from colonial and capitalist exploitation while refusing to concede to an apocalyptic vision of the future. This politics of doom can be seen as attempts by the same forces to render impossible the overcoming of the multiple crises that they themselves have produced. The Biennale of Sydney proposed instead the radiance and warmth of ten thousand suns, illuminating a collective future that is not only possible, but necessary to be lived in irrepressible joy and plenitude, in common humanity.

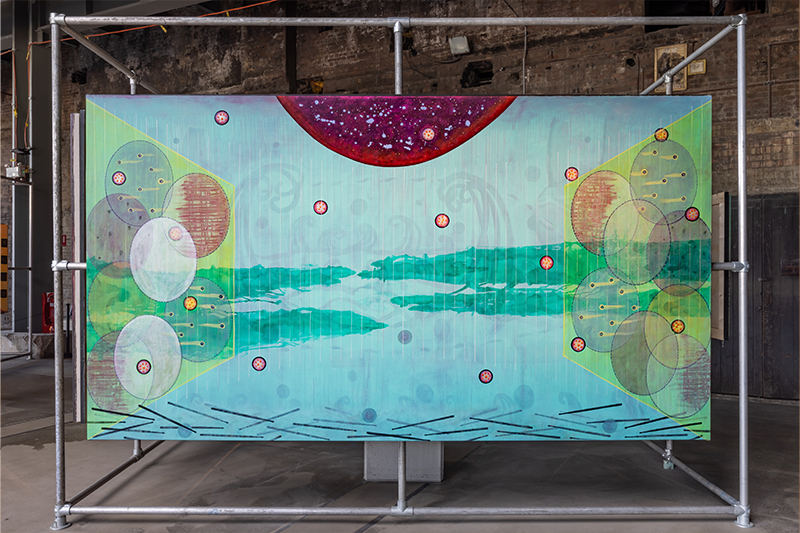

Photograph: Document Photography

Front to back: Satch Hoyt, Ice Pick, 2002; I Contemplate My Dharmic Journey, 2019; On Galactic Paths of More Tomorrows, 2017. Courtesy the artist. © Satch Hoyt. Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, 2024, White Bay Power Station.

Left to right: Satch Hoyt, The Calling in of the Silent Codes, 2019; Tangled Migrations-Calvary-3 (for Prince), 2016. Courtesy the artist © Satch Hoyt. Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, 2024, White Bay Power Station.

Satch Hoyt, Feel Their Breath Vibrate in 6/8, 2019. Courtesy the artist © Satch Hoyt. Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, 2024, White Bay Power Station.

Satch Hoyt, The Dream is Serial not Token, 2017. Courtesy the artist © Satch Hoyt. Installation view, 24th Biennale of Sydney, Ten Thousand Suns, 2024, White Bay Power Station.

For the Biennale, we were interested in presenting sound through its histories as part of different collective forms of resistance. Works by Satch Hoyt, for instance, presented a series of pictorial sonic mappings—canvases composed as musical scores holding the flux of sonic inheritance that came through the Middle Passage, the enslavement and kidnapping of people from the African continent to the Americas. Some of these paintings are also informed by the artist's research into colonial recordings of African music, where he “un-mutes” sound or instrument collections captured during the European colonial period, linking anthropological recordings to the sounds of contemporary Black culture. Aside from these powerful images, Satch also presented musical cases showcasing precious sculptures melding an afro-comb with the Black Power fist. Used as instruments, the artist recorded the sound of the comb brushing out Black afros, crafting rich compositions loaded with ideas of resistance, empowerment, and liberation.

Photograph: Document Photography

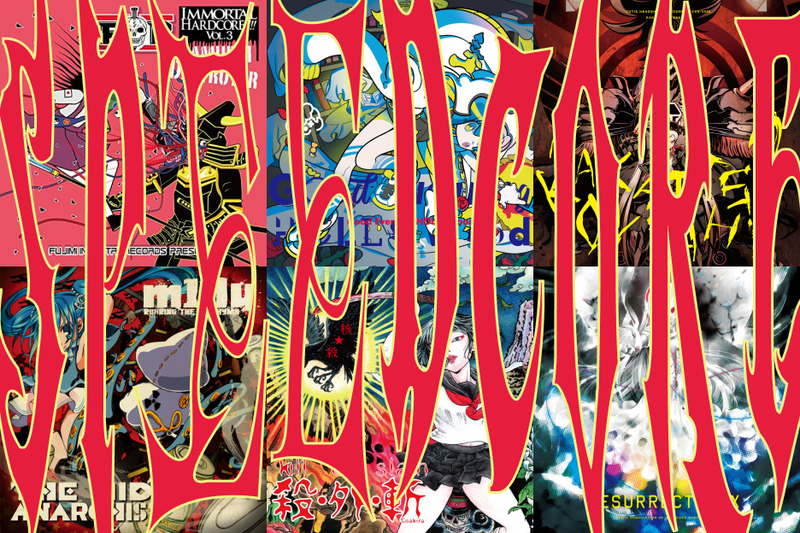

Afrosonic reincarnations that took place in the Americas also contributed to the music genres played in the Picó sound systems in the Caribbean region of Colombia: cumbia, champeta, Congolese rumba, or Afro pop, amongst others. Picós are beautiful examples of how technology (in this case, the electromagnetic technology that makes up the inner construction of the sound system) has created new forms of collectivity. The beats gather crowds around these humongous sound systems, bringing to life a new tradition since the 1970s, which opens up another way for us to think of connections between tradition and technology.

Photograph: David James

The biennale also included artistic experiments with recording music, such as those by Niño del Elche and Pedro G. Romero. The artists have been looking at histories of flamenco as a genre of resistance and at its iconography that has deep connections with the colonial history of the Pacific and the presence of the Spanish Empire in the Philippines, Guam, Marianas, Palau, and the FS of Micronesia. Their work O sea, antípodas, puesto del revés y boca abajo (And just like that, antipodes, turned upside down) creates a cartography of sound, where flamenco singer Niño de Elche performs nine songs linking several musical traditions. Following antipodean connections and old Galleon Trade routes, the songs travel between Mexico, Thailand, the Philippines, Japan, Indonesia, Aotearoa, and Samoa. In the Biennale, these songs were played in large-scale speakers with stretched flamenco shawls as speaker cover mesh. Known as Manila shawls, these colorful silk fabrics worn by flamenco dancers are a hybrid commodity linked to Spanish colonial presence in the Philippines, where Chinese businessmen in Manila added fringes to floral silk fabrics embroidered not too far away in Canton, specifically for the Spanish market.

The joy of cultural multiplicities affirmed, and of carnivals as forms of resistance rallying against colonial oppression and dehumanization.

Photograph: David James

Indonesian vernacular forms of music and their post-war history are shown in the work of Choy Ka Fai who, amongst the vast areas of music and performativity (amongst other things) he has been researching, looked at IndoRock for the Biennale. This is the rock’n’roll played in the Netherlands, and later also in West Germany, by mixed-race or Dutch-speaking Indonesians referred to as “Indos.” The musicians who were later to become part of groups like the Tielman Brothers, came from “Indo” families forced to leave for the Netherlands in the new context of the Republic of Indonesia. Many of the exiled men who had guitar-playing skills ended up being part of bands in their new life as immigrants. Choy Ka Fai created an impossible meeting of history where the lyrics of popular 1960’s IndoRock songs are performed and interpreted by Tik Tok stars Dewi Arum Girls—women-led music and dance groups in Indonesia cosplaying Dutch soldiers, which is a tradition known as Dolalak that exists since the 1930s. Here, parody (which has a venerable tradition in the Indonesian context as a cultural form of speaking truth to power) becomes a form of resistance manifested in music, collective dance, and social theater. In each of the examples above, genealogy, tradition, antiquity, and particular cultural lineages are fundamental to the process of resistance. Likewise the creolization of these traditions that occurred in all these contexts are also decisive for the politics around them.

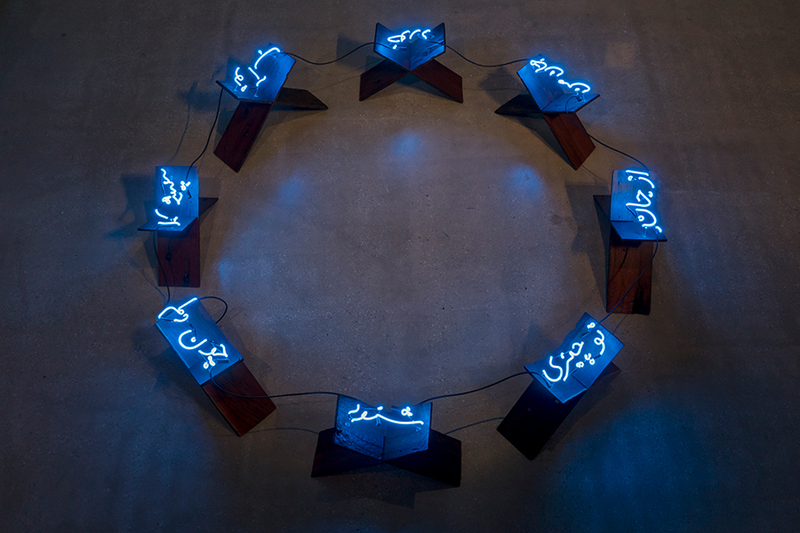

Photographed by Jacquie Manning

In another work, Elyas Alavi looks at very particular histories of the so-called Afghan cameleers in Australia, who had been brought in the 19th century by the English colonial authorities to take care of camels that were needed to conquer the central and western parts of the Australian continent. The cameleers came with their own knowledge, Sufi philosophy, and cultural rituals, largely manifested in musical practices, in particular through the introduction of the rubab instrument to the dessert of central Australia. Between 1860 and 1920, Australia relied upon mostly Muslim cameleers primarily from South Asia, as well as Southwest Asia and North Africa, generically and mostly erroneously known as “Afghans.” These men were relocated to Australia to transport supplies, communication infrastructure, and settlers between regional outposts. It was these men who built the Overland Telegraph Line, linking Adelaide in the South to Darwin in the North (and from there with the grid of the British Empire), and the Trans-Australian Railway. Yet the cameleers were vilified by the media of the time, and suffered discrimination in government policy, being granted only temporary visas and refused naturalization. As they traversed the nation’s interior, their tracks intersected with those that had already been established by First Nations peoples and so formed an intercultural bond. Alavi, an Afghani immigrant living in Melbourne who arrived in the country at a much later date and in different circumstances, connects to and memorializes the wisdom and philosophy the cameleers carried in their music.

The Australian context is a continental and polyphonic one. Sydney itself has its own choruses of communities, while its cultural institutions have been going through processes of decolonization in the past decades. The Biennial engaged with this multiplicity of cultural lineages that different parts of society identify with, inviting different worlds to come together. Music has often been the best suited medium to facilitate that.