Wikimedia Commons

What attracted Russian wanderers to the distant East? What benefits did travel hold in store for them? And to what degree did borders prevent ordinary Russian merchants from becoming pioneers of global geographical discoveries? Historian Alexander Radaev speaks about Russian travelers who reached West Asia in the early Middle Ages and discusses historical documents that kept the memory of their wanderings.

We know well that at the time of the birth of Christ, any reasonably well-educated and not necessarily wealthy person could get from, for example, the Arabian deserts to somewhere in the depths of contemporary Nepal. Here he could eagerly become acquainted with the basic tenets of Buddhism, and within a couple of months, would have been able to mull their viability back on his native desert earth, surrounded by familiar goatherds. Travelling between distant countries in antiquity took a long time, though it was complicated not so much by cartographic factors as by the quality of the equipment of the expedition itself, high costs, and a lack of language skills, as well as natural and climatic reasons—in short, it wasn’t so different from today.

So if somebody tells you that a person could only gain a profound knowledge of the world from the Age of Discovery onwards—don’t believe them. Let us take a look back at the most famous travellers of antiquity—my fellow Russian countrymen who had already travelled half the world at the turn of the second millennium.

The road to the Middle East was already familiar to my “compatriots” in the sixth and seventh centuries. At this time, the Slavs were either fighting in the ranks of the armies of Byzantium or attacking Byzantium themselves. The links between the Slavs and the peoples of the East have endured ever since. Russian soldiers were in Amastrida, in the south of the Black Sea region, in 842. Russians fought in Macedonia, Syria, and Armenia in the tenth and eleventh centuries, and written sources tell us of Russians trading with the countries of the East in the 840s.

The twelfth-century Primary Chronicle is the earliest written document of the history of Kievan Rus’, the Russian proto-state. It mentions not only the countries of Western Europe and the Balkan Peninsula, the Crimean ports of Surozh (Sudak) and Chersonesus, but almost all the states of the Mediterranean, the Caspian Sea, the Middle East, and along the Nile. Among these places are the river Tigris, “between the Medes and Babylon,” Armenia and Media; Lycia, Cilicia, Caria, Phrygia, Libya, Egypt, the “river Gihon, called the Nile”; Arabia, Babylon, Phoenicia, Mesopotamia, and Syria, from “Media to the Euphrates River.” This is an incomplete geographical list, mentioned in connection with the story of the inheritance of Noah’s sons Japheth, Ham, and Shem.

For an early medieval author and reader in Russia, however, it was not only biblical legends that served as a source of information about the geography of the East, but also contemporary documents, treaties, chronicles, and descriptions of daily life. And acquaintance with the numerous countries of the East was far from theoretical: it relied on the accounts of people whose own eyes had seen these distant lands and who had preserved their descriptions for retelling in their homeland.

So it is, therefore, no accident when a chronicle states that from Russia,it is possible to reach the tribes of Ham and Shem by water. The water route from the north separated into two directions: the first—from the Varangians (Vikings) to the Greeks–led to the Mediterranean Sea, skirting southern Europe; the second led to the Black Sea via rivers. Water transport was the quickest, but any route consisted of overland stretches between navigable water bodies. It seems that over the past millennia little has changed here. Border control included the collection of duties, which were usually taken from the cargo being transported—depending on the quantity—seven, nine, ten, or forty units of each kind of goods. In addition, the traveller could fall victim to all the same dangers as now: the loss of a landmark or provisions, gales and storms, illness, attacks by bandits or enemy soldiers.

Right: The Byzantine fleet repels the attack of Rus’ on Constantinople in 941. Miniature from the Synopsis of Histories (Σύνοψις Ἱστοριῶν) by John Skylitzes, 13th century

Madrid National Library

The city mentioned most frequently in Russian chronicles, and in great detail at that, is Tsargrad (Constantinople), so beloved of Russian “travellers.” Admittedly they were soldiers, to begin with, as a rule. Kyi, the founder of Kiev, headed for the lands of Constantinople for battle in 854; the Kievan rulers Askold and Dir also went there to fight in 866; in 907, Oleg attacked Byzantium; in 911, the embassy of Prince Oleg went to Byzantium to seek agreement between Russia and the Greek state; in 941, Igor led an expedition to Constantinople and beyond to Paphlagonia and Bithynia on the southern shores of the Black Sea; in 944, Prince Igor made a pact with the Greeks; in 957, Olga of Kiev was baptised in Constantinople.

Olga’s stay in Constantinople would periodically reappear in later sources. In the 1200s, one Russian traveller would say that in the cathedral of Hagia Sophia, he had seen a golden dish given by the princess to the church in which she had been christened. By the fourteenth century, the Russian diaspora in the East had formed actual Russian colonies here and there.

After the Christianisation of Rus’, such military expeditions—like, for example, the unsuccessful one by Prince Vladimir of Novgorod in 1043—became more seldom, unlike journeys to Arab countries with commercial aims, which became more frequent. Yet productive trade had also existed at an earlier time; a fact confirmed—apart from in foreign texts—also by archaeological discoveries. Primarily, these are hoards of Arab coins from the eighth and ninth centuries, brought to Rus’ by merchants returning from their travels. In epic texts, you can encounter mentions of gold transported out of Arab countries, yarovitskaya (that is, Arabic) copper and white-crushed kamka, as well as an old-fashioned type of silk tissue—the very same foreign cloth that the fairytale character Solovei the Brigand presents Princess Apraxia (the wife of Kievan ruler Vladimir the Great). “Kamka is not expensive–but the pattern is complex. The cunning of Tsargrad is imprinted on it, the wisdom of Jerusalem, the scheming of Solovei Budimirovich himself.”

In the writings of the Arab geographer Ibn Khordadbeh, meanwhile, we find these details: “Russians from the Slavic tribes export the furs of beavers and black foxes from the very furthest reaches of the Slavic lands and sell them on the shores of the Russian Sea; here the Russian king takes tithes from them. When they are of the mind, they go to the Slavic River and arrive at the bay of the city of Khozar; here, they give tithes to the ruler of this country.”

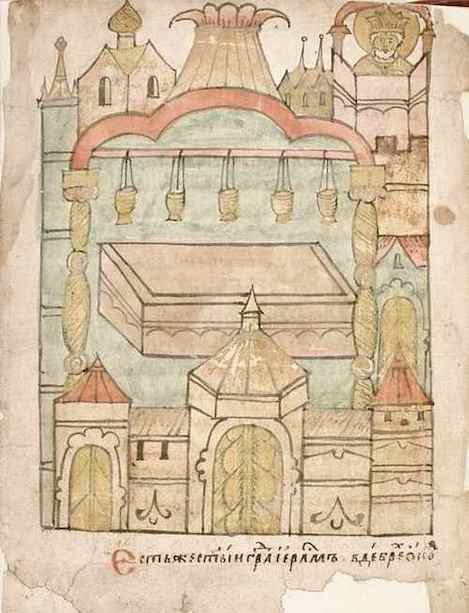

The State Historical Museum of Russia / Wikimedia Commons

From 988 onwards, it was not only Russian merchants and men-at-arms who could boast of travels in Turkey, Palestine, or Egypt but also ministers of the newly founded church. The Russian clergy became frequent guests in the countries of the East, mainly because the Kiev metropolitans were appointed in Byzantium. Private journeys with no economic, military, government, or political goal were also becoming possible.

In the late tenth and early eleventh century, the first pilgrim “tours” left Rus’, documented by the chronicles and other written sources of the time. In the Russian chronicles from the eleventh century, we find records of journeys not only to Byzantium but also to Mount Athos and Palestine.

We can judge the popularity of such “tours” by the sheer number of them. In particular, pilgrimages to the river Jordan and to the Holy Sepulchre, which began in the late tenth century, were made by groups of forty or more people, which for the time was substantial.

In the twelfth century, the first Russian travelogues began to appear. The travel genre became an extremely popular literary product. To become a celebrated author, it was enough to head for distant lands, be observant—and of course, to be literate, in order to put down in detail everything seen. The oldest written description of visits by Russians to the East is probably The Life and Pilgrimage of Daniel, Hegumen from the Land of the Rus. It contains accounts of the acquaintance of the people of Rus’ with the economic geography, ethnography, economics, and other information about life in eastern countries in the early 1100s. Hegumen Daniil (an abbot, probably from a monastery in Chernigov), who travelled in the time of Sviatopolk II of Kiev, left a remarkably comprehensive description of Syria, Palestine, and the eastern Mediterranean region. Not only this, but the traveller carefully recorded the distance between cities and geographical sites, which has been of considerable help to modern archaeologists.

This work has benefitted not only writers but also historians. The abbot from southern Rus’ came to the East in the period between 1109 and 1113, at the very time when Jerusalem had just been taken by the Christians, and the beautiful buildings of the city and its surroundings had not yet been destroyed. Besides excursions into biblical topics, Daniil gave in-depth economic, geographical, and everyday characteristics to all the destinations on his long journey. In this way, we learn what was grown, mined, produced, traded, and in demand, and in which region. There are other—very engaging—details. For example, he recounts the technologies for collecting rainwater in Middle Eastern cities that were not located near bodies of water and other water sources.

The Israeli miracle of the twentieth century—a flowering oasis amid the desert—was nothing unusual by the standards of the twelfth century. Hegumen Daniil notices flowering gardens at the walls of Jerusalem, figs, olives, berries, grapes, “vegetable” (fruit) trees, generous wheat, and barley, “which will be born in stone without rain.”

The hospitality of the local population did not escape the keen gaze of the “tourist” from Rus’. He writes that both Christians and Arabs paid him special attention. Additionally, Daniil mentions meetings with the local Russian community, which had already formed by that time in the Holy Land. Many Russians truly did not want to return to their homeland from warmer climes: some had chosen to stay from the time of the embassy of Roman the Great of Kiev (1203), others became permanent scribes and translators of books, joined a foreign militia or, realizing the benefits of local trade representations, moved their families and settled there.

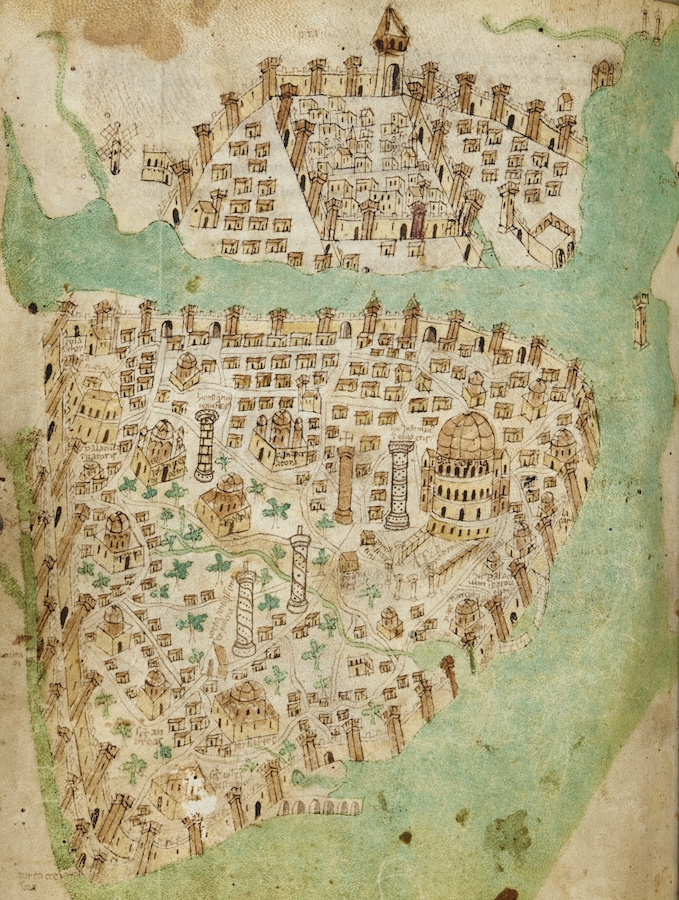

Cotton MS Vespasian a.XIII.art.1, f.36v / The British Library

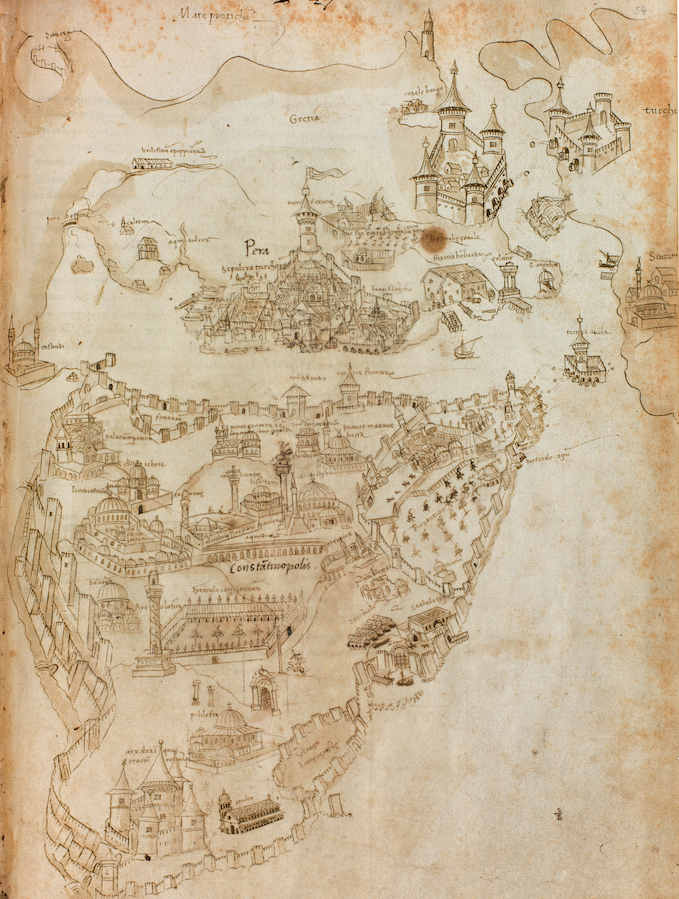

Right: Map of Constantinople by Cristoforo Buondelmonti from Liber insularum Archipelagi, 1485–1490 год

Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek, Düsseldorf

These peregrinations, or khozhdeniya, won recognition due to the colorfulness, liveliness, and most importantly, the authenticity of their stories. Two important texts on the subject of the East appeared at the beginning of the thirteenth century: a description of the journey by archimandrite Dositheus to Mount Athos and the travels of Dobrynya Yadreikovich, a future archbishop of Novgorod, to Constantinople. Dobrynya named his book Pilgrim and included a description of the city’s attractions and sites that had made a particularly strong impression on him: for example, that “water is brought up through pipes,” and that horses were traded at the huge forum of Constantine.

Even during the times of the crusades to Byzantium and Mongol-Tatar dominance in Russia, Russians continued to travel to the East, though few of these journeys appear in written sources. And future archbishops of no little means, and ordinary laymen, whose life was especially weighed down by the vicissitudes of a time of significant changes, continued to journey to Zion, Turkey, Greece, and distant Egypt. In the 1300s, 1350s, 1370s, and 1400s, they appear in Asia Minor and the Eastern Taurus, in Sinop and the Bosphorus and Penderaclea, despite the logical and political difficulties.

The way of life and very configuration of Eastern cities continued to be of vivid interest to tourists: they paid attention to important events like coronations, at sites of significance such as the patriarchal baths, monuments of art, the harbors of the Mediterranean, filled with ships, the lifeless environment of the Dead Sea, the glass factories of Hebron, ships with 200-300 oars, the “birth” of sugar in Cyprus, the melons and heavenly apples of Jordan, trading in Ramla, “high mountains resting against the clouds,” copper pillars with snake heads, equestrian statues of rulers, the hippodromes of Constantinople, and the hospitable Sinopians.

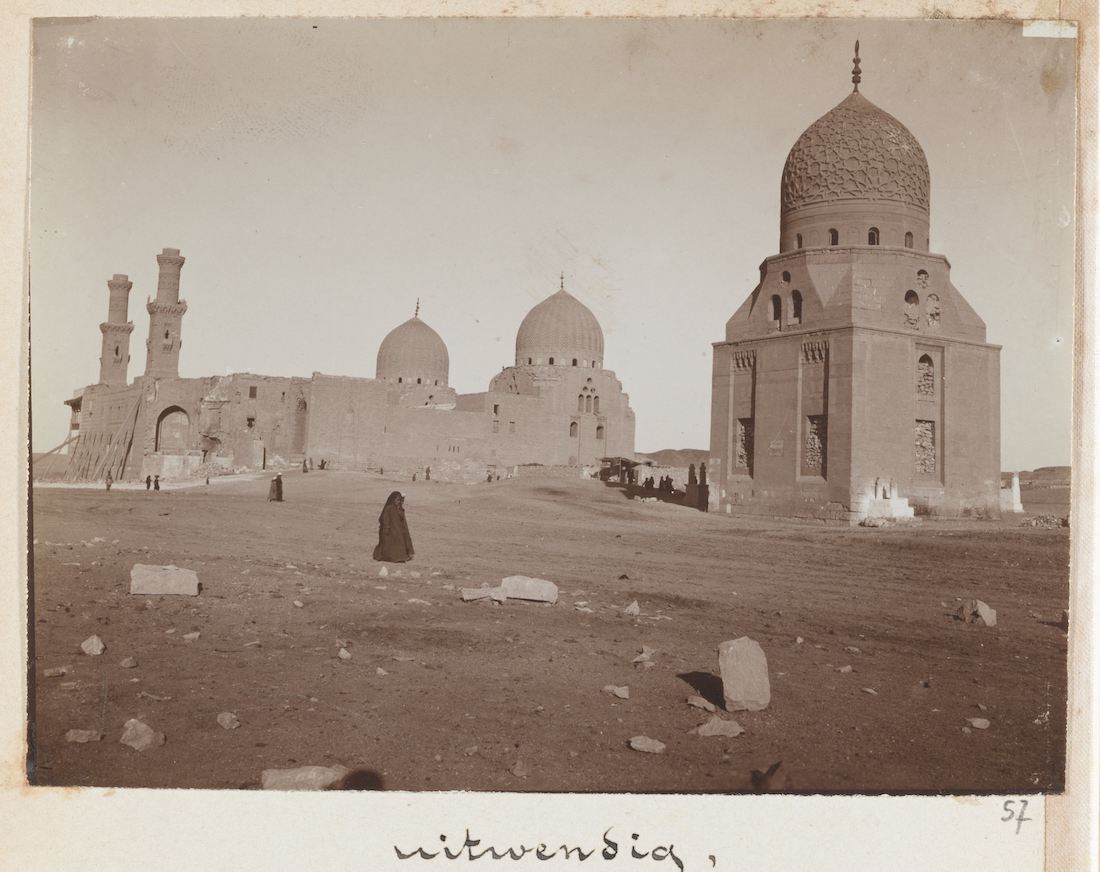

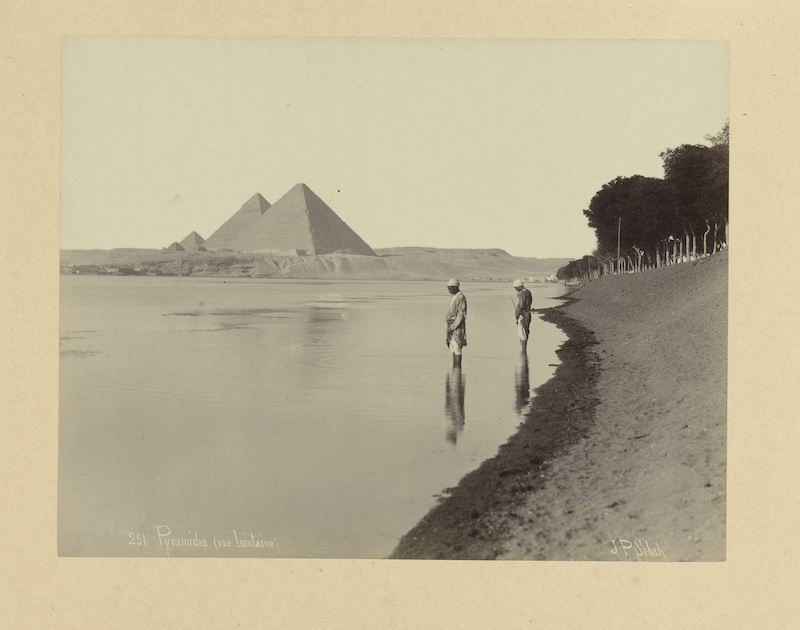

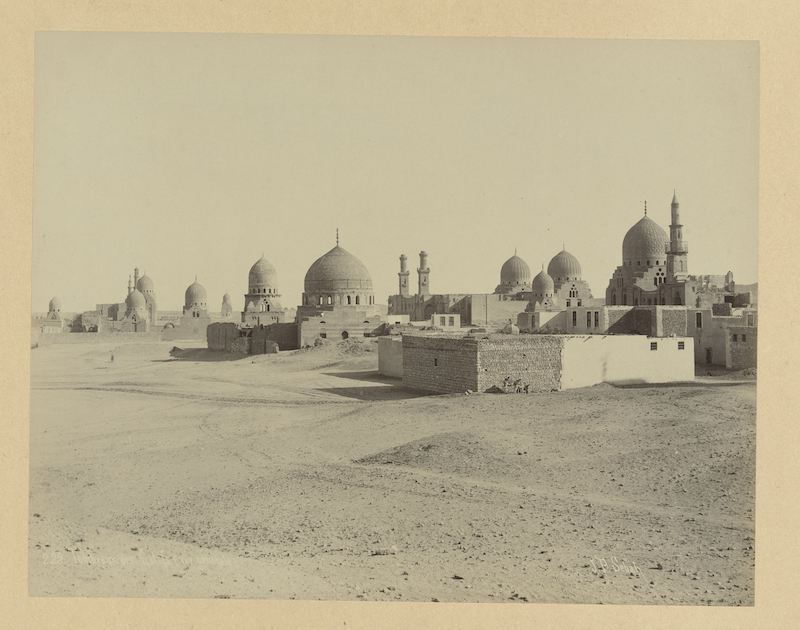

Bottom: Pascal Sébah. Cairo, 1888–1898

Rijksmuseum

As the centuries passed, Russian travellers turned from curious and meek observers into knowledgeable wanderers, experienced merchants, and genuine envoys of the goodwill of their princes. It was not without sympathy that the Rus’ court in Kiev reflected on the siege of Byzantium by the Turkish Sultan Bayezid in the fourteenth century. When the position of the Byzantine emperors became precarious, the Grand Duke of Moscow Dmitry Ivanovich and Prince of Tver Mikhail Alexandrovich sent considerable monetary support to the emperor and patriarch with trusted envoys.

Over the centuries, the travel memoirs of Russian pioneers built up into a chronicle of the gradual and irreversible decline of the once-flourishing Byzantium, always so attractive for the distant Slavs. At the same time, against the background of descriptions of the wealth of the East, a picture takes shape in many of these written monuments of Russia’s development and growing power, overcoming adversity and the victory of Russia over the Mongol-Tatar yoke.

And so, after seven or eight centuries of uninterrupted links, Russian travellers begin to write not about the alien, unseen East, but about the kindred lands close to them: in 1414, Grand Prince Vasily Dmitrievich gave his daughter Anna to the son of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, whose accession is described in the Notes of Ignatius Smolyanin, who left Moscow on April 13th, 1389. Princess Anna’s journey was captured for us by Zosima, a monk from the Trinity Monastery of St. Sergius: from Moscow to Kiev, from there to the Principality of Moldavia, to the city of Cetatea Albă (Akkerman), and then by water across the Black Sea. This would be one of the last Russian journeys to Christian Constantinople. Contemporaries in Russia would find out about the city’s capture by the Turks from a chronicle by the Russian writer Nestor Iskander. From this moment, advanced Russian society began to take an interest in Turkey: as a powerful state, a likely adversary, and a beneficial partner. The ancient routes returned to life, and travellers on official, commercial, and spiritual business now went to the Muslim East: from Tsargrad and Bursa to Palestine and Cairo via Antioch, Adana, Konya, and Karahisar.

Many cities in Asia Minor are described for the first time in The Travels of Guest Vasily, an account of a Russian pilgrim’s travels in Palestine and Egypt in 1465 and 1466. Particular attention is paid to their fortifications, caravanserais, irrigation systems, and city plan, baths, markets, the thickness of their walls, iron gates, arrow slits, the size of the rivers, and details such as a caravan of 10,000 camels. In Cairo, Vasily counts 14,000 streets with oil lighting, gates, and guards, and 15,000-18,000 houses on each street. He also indicates the size of the city: twelve miles long and two miles wide. The river—the Ghion, or the Nile—made a particular impression on the traveller, who described it as “flowing from paradise.” Vasily was struck by an incredible tree on which “honey” grew (that is, the date palm) and a fierce beast—a crocodile.

Afanasy Nikitin’s now canonical fifteenth-century A Journey Beyond the Three Seas undoubtedly merits special attention: it is the most outstanding example of ancient Russian writing in which the Middle East is mentioned. Nikitin stayed in Tabriz (Iran) on his way back from India and then visited the Black Sea ports of Trebizond and Kafa. The story of Nikitin’s journey excites many researchers and enthusiasts: the enterprising man from Tver visited India at a time when the European courts were just wondering how to reach its coveted shores of Malabar. Having shrewdly invested 100 rubles in a thoroughbred horse, the merchant got at least three times the price for it in India, which allowed him to travel in financial comfort for several years.

Ancient texts reveal a multitude of graphic details about distant lands seen by Russian people with their own eyes. In times when the majority of European states were seeking frantically to establish contact with the mysterious kingdoms of the East—from the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean—Russians had long known of them, traded with and befriended them, remaining inquisitive observers, tireless travellers, and reliable comrades. This trend continued until the nineteenth century when the British—not without respect—discussed the Turksib rail project, which firmly linked the remote territories of Central Asia with European Russia. But that is already another story.