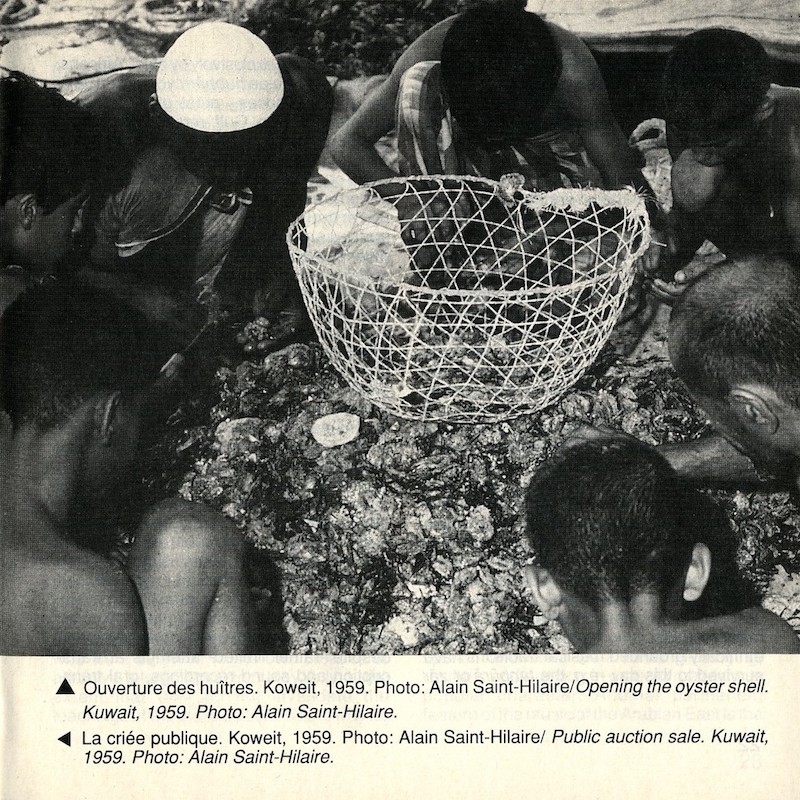

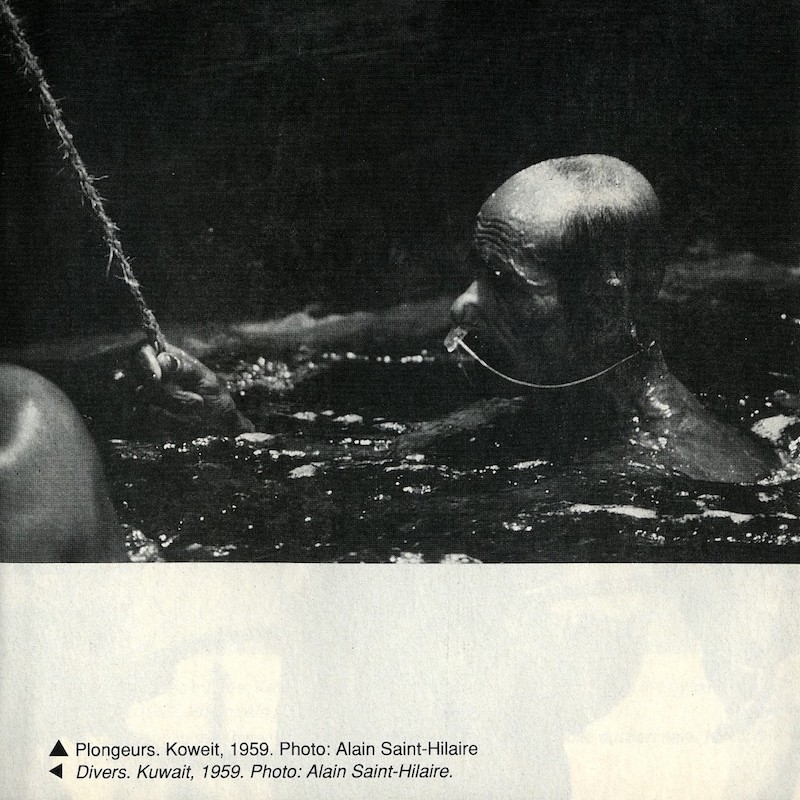

Before the discovery of vast oil reserves in the 1930s, the way of life in the countries of the Persian Gulf differed significantly from the present one. The overwhelming majority of the male population of modern Bahrain, Qatar, Kuwait, and the adjacent territories was engaged in crafts directly related to the sea—they were fishermen, shipbuilders, sailors, and pearl divers. The latter industry, already quite exotic if measured against today's standards, was then the most profitable—especially for ship captains and merchants who resold pearls to other countries. However, for ordinary divers, among whom there were many slaves from East Africa, this occupation was also considered noble, although very difficult and dangerous. Pearl hunting expeditions could last up to four or five months, with many divers suffering from malnutrition, anemia, scurvy, trachoma and with some dying from attacks by swordfish and sharks, or simply drowning. “We are all, from the highest to the lowest, slaves of one master—the pearl”—these are the knownknownR. Kirkpatrick, “British Museum report on the Persian Gulf as a possible area for successful sponge fisheries,” 1905. words of the first leader of the Qataris, Mohammed bin Thani.

It is not surprising that numerous musical and vocal practices have arisen around such a specific, and at the same time massive, occupation. Collectively, they are commonly referred to as fijiri (Arabic: الفجيري), but are also included in the broader category of fann al-baḥri (maritime arts).

Like the profession associated with this musical tradition, fijiri was considered an art that was inaccessible and dangerous for ordinary people. This image has developed due to the fact that the tradition is credited with supernatural origins. According to one versionone versionHabib Hassan Touma, “The Fidjrí, a Major Vocal Form of the Bahrain Pearl-divers.” The World of Musiс, Vol. 19, No 3/4, 1977. of the legend, during a long trip three wanderers from Dilmun ended up in a mysterious mosque, where they met ancient demons—jinns. These creatures, who appeared in the form of half human, half donkeys, taught travelers the songs, however, they forbade them to speak about what had happened to them on pain of death. And only when he had become an old man, on his deathbed, one of the travelers revealed the secret to his friends and relatives and passed the knowledge of fijiri on to them.

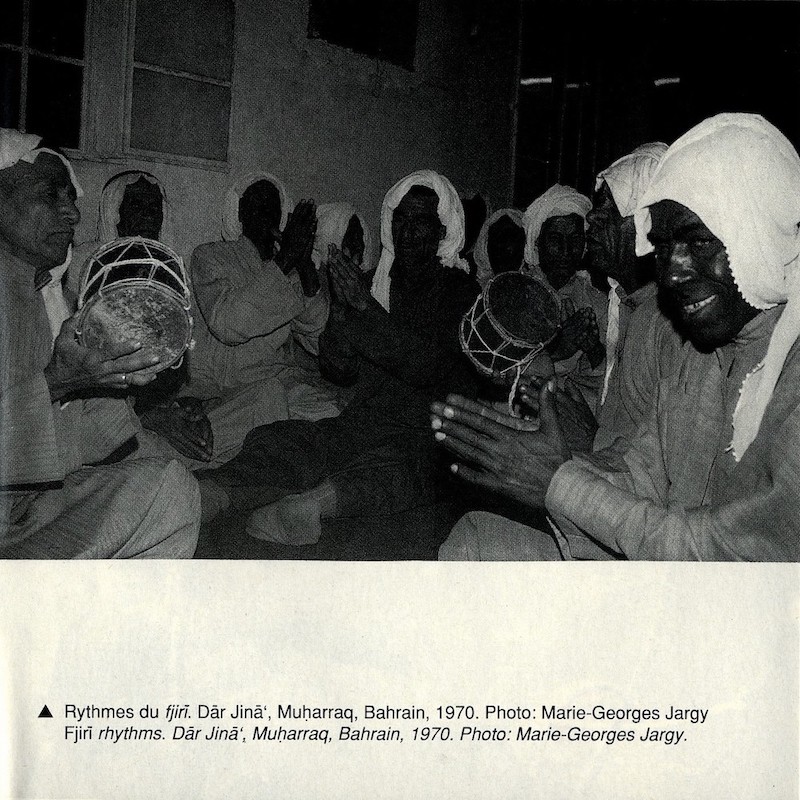

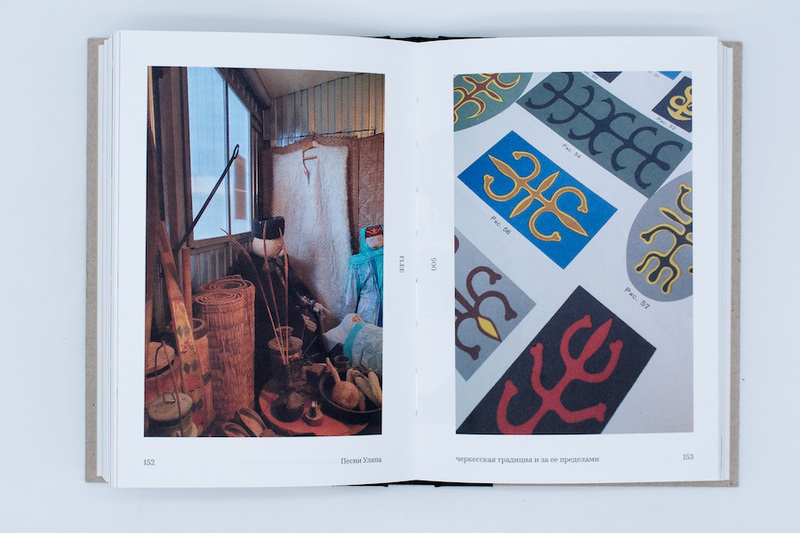

Most songs were sung by members of the ship's crew at weekly meetings between trips. The gatherings took place in a special building called dar, which was sometimes the captain’s home. Up to forty men could attend such a meeting, where they drank coffee and tea, smoked, remembered the hardships of sailing, and danced until the dawn prayer—fajr, that, according to one version, gave its name to the genre.

Also, there are separate kinds of songs known as “ahazij” or “nihma” that were performed as accompaniment to certain types of ship work. “Meydaf”, for example, was sung while rowing, “basseh” and “qaylami”—when going on a big or a small trip, respectively, and “khrab”—when pulling the rope while raising the anchor. In all the songs, the form of work mainly directly influenced their musical composition.

Many fijiri feature a so-called “call and response” structure that is common in many workers’ songs around the world. To perform the central part, the captain of the ship (nawakhthah) hired a soloist called nahhām. This person was the only one who, during the voyage, did not do any other work except sing, keeping the sailors’ spirits up. The Nahhām sang poetic verses with a very detailed melody in a high register. A chorus of sailors responded to the soloist, reacting to his phrases with ecstatic, enthusiastic shouts with their voices forming a dronedroneA minimalist music genre that emphasizes the use of sustained sounds, notes, or tones.-like melodic pattern several octaves lower. This unusual effect, not found in any other genre of Arabic music, apparently mimicked the sound of the sea that divers could hear when diving to the bottom.

Archives Internationales de Musique Populaire

Fijiri lyrics describe the divers’ hard life, the dangers that await them on the voyage and at the bottom of the sea, and the joy of reuniting with their families. In the texts, they often touch upon mystical themes. Appeals to God contrast with images of earthly suffering: references to wounds, fate, and the overwhelming power of the sea.

Researcher Nasser Al-Taee gives his translationtranslationNasser Al-Taee, “Enough, Enough, Oh Ocean.” Middle East Studies Association Bulletin, Vol. 39, No. 1 (June 2005). of Murshild bin Sa'd al-Bitali’s fijiri poetry into English:

They fight death and all its elements

While smiling

O how I suffer from the long nights

Witnessing those motherless divers

Every time a month passes by, another follows

Until the eyes grow old

The musical arrangements of fijiri are performed without melodic instruments and singing was accompanied mainly by clapping. A number of percussion instruments are also used in musical gatherings in dar. Among them there are two types of double-headed cylindrical drums (tabl and mirwās), a single-headed frame drum (tar), a small plate (tus) and clay vessels for water (djahlah). The music is complemented by slow body movements that are not found in any other Arabic dances. The dancers' hands are raised up and down, touching and massaging the body, which symbolizes healing. The slow dance is interrupted by sudden jumps that signify the divers' rapid plunge into the water.

With the rise of cultured pearl technology in Japan and after the discovery of oil in the Gulf, the culture of pearl hunting started fading away. Already, by the late 1960s when the British ethnomusicologist David FanshaweDavid FanshaweDavid Fanshawe, African Sanctus: a Story of Music and Travel, 1975. arrived in Bahrain hoping to hear and record divers’ songs, there were only four ships still engaged in this kind of fishery—all of those at sea. To record a ritual song that accompanies the raising of the anchor, he had to resort to special tricks: the sailors he had managed to find performed it on the shore while pulling an old rope tied to a bus wheel that stood for a ship anchor chain.

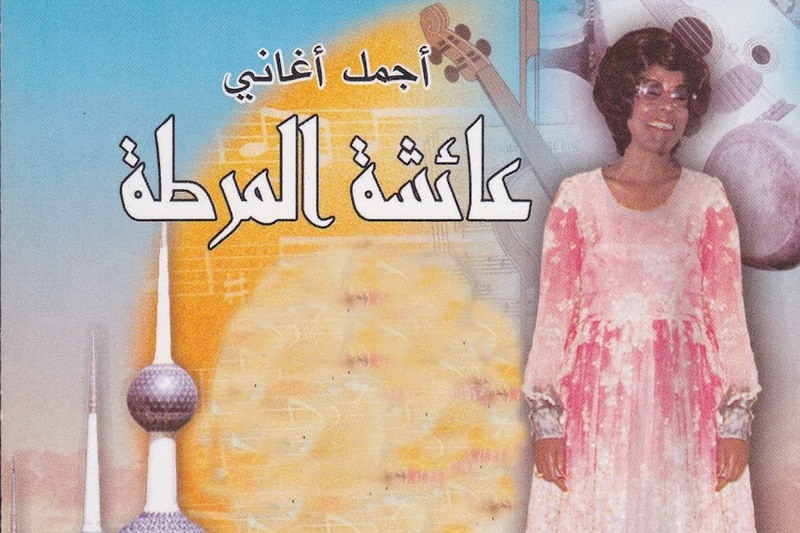

However, in the 1970s this tradition was again recognized and included as part of conscious steps made towards preserving cultural heritage. The commercial value of pearl hunting disappeared, and thus it became almost impossible to perform work songs directly during the process of labor. But the tradition of singing songs in special dar houses has been given special attention, passed on to the next generation and supported by the state. These days fijiri can now be heard, for example, in shopping malls or concert halls, where classical elements of the genre are combined with symphonic music, performance practices that are much more related to Western European traditions. Contemporary electronic musicians and multimedia artists of Arab origin have made attempts to reinterpret fijiri, however, such experiments are still very rare.

You can find out more about pearl diving culture in the Persian Gulf from the documentaries by Jamal al-Amed “Bahrain: Pearl Journey” and Hashim Mohammed “Al-Funun.”

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich