EastEast is proud to present an essay written as part of the exhibition Land of Fire / Țara de foc at Kunsthalle Bega, Timișoara, Romania (18 October 2024 - 2 February 2025). Departing from several lesser-known historical episodes, the exhibition is interested in some lines of exclusion in both historical and art historical discourses in Romania. Land of Fire examines genres, styles, languages, media and artistic genealogies have been excluded, often at the expense of complexity, from the dominant art historical narratives used to construct the nation’s self-image; this includes the subject of Ion Dumitrescu’s work: hybrid music genres that are still a point of contention in Romania today.

We can affirm, of course, without hesitation, that Turkish music is closer to perfection, in terms of measure and harmony of voices, than any European music and, likewise, it is so difficult to learn that in Constantinople, a city at the intersection of many continents, home of the most great Courts throughout the world, the Eastern Council, among so many musicians and music lovers, one can hardly find three or four who have deeply understood the meanings of this art.

— Dimitrie Cantemir (1716)

Dimitrie Cantemir (1673 – 1723) spent his childhood as a devşirme (aristocratic child prisoner)—a specific category of slave in the Ottoman empire, the throne inheritor of a vassal state to be held as a guaranty of that state's submission (in this case Moldavia), but also for the offspring of its colonized elites to be raised and educated at the Sultan's court in Constantinople.

While at the court, Dimitrie Cantemir (Cantemiroglu) became a virtuoso of the tambur (a precursor to saz) and also started to compose for the Sultan's events.

His musical revolution at the Ottoman court at the beginning of the eighteenth-century consisted in reforming the notation method and even more remarkably, writing its first history, Kìtâb-i Ilmül Müsîkî ala Vech’l-Hurûfât (The Book of the Science of Music According to the Alphabetic Notation), archiving its numerous influences (Armenian, Sephardic, Persian) in his compositions. Through all his endeavors he promoted and made Turkish more accessible to the Western hemisphere. Achieving many scholarly feats and considered a pioneer in many disciplines, as writer, philosopher, and proto-ethnographer, Dimitrie Cantemir employed a transnational approach, taking cues from Byzantine theology and Greek philosophy, Western Enlightment and Russian lore. A new, modern and non-belligerent approach to intellectual navigation that would make a clear demarcation to previous Moldavian or Wallachian princes and kings. Cantemir thought and wrote across cultural frontiers. His erudition did not place the West in the center of his system and just like the lăutari in the coming centuries, he was able to culturally traverse empires and defy colonial directives.

The Classic Age of Lăutarie

In 1939, at the New York World's Fair "The World of Tomorrow," Romania held parades in folk costumes, with peasants marching as symbols of "Românism"(term heavily used by inter-war fascists in RO), while in the Romanian pavilion Maria Tănase, accompanied by Grigoraș Dinicu (1889 - 1949) and his orchestra of lăutari, were greeting the visitors. But the presence of lăutari was nothing unusual, on the contrary, for almost a century by then, Romania was represented at universal exhibitions by Roma lăutari. Grigoraș Dinicu himself performed in Paris at the 1937 edition, and the more you go back in time, even in pre-Romania, you discover that Cristache Ciolac (1870 - 1927) was at the 1900 edition, while Sava Pădureanu (1848 - 1918) represented the recently united Moldavian and Wallachian principalities at the universal exhibition in the city of lights in 1885. Cristache Ciolac tells in an interview how he and his orchestra were almost mandatory during the official visits at king's court in Sinaia and Bucharest but also intensely required at the weddings of boyars and Bucharest's in vogue terraces and restaurant-gardens. Sava Pădureanu had spent 6 months in Russia at the invitation of Tsar Alexander III. The fame he enjoyed in Petersburg was so great that, at the height of his career (1894 - 1904), "Pădureanu" champagne and cigarettes could be found in the Russian trade. He was decorated by both the Tsar and King Carol I of Romania.

In addition, as historian A.D. Xenopol (1847 - 1920) and the folklorist Gheorghe Dem Teodorescu (1849 - 1900) have attested, the Romani lăutari have kept alive all ethnic folk traditions (from Bessarabia to Oltenia), performing a vital function also for "Românism" ideology. By playing for centuries Doinas, ballads, "ciocârlii" and other immemorial folk hits, they were acting as archivists, internal and international distributors of the cultures of the Romanian principalities. Starting with Barbu Lăutaru' (1780-1858) the lăutari were true ambassadors of pre-Romania. Paradoxically, although maintaining an institutional racism system across their territories even after the abolition of slavery (1856), the RO aristocracy (voivodes and boyars) of the previous centuries have always prided themselves by representing their particularity and contribution to the universal heritage through Roma lăutari.

Sava Pădureanu, Cristache Ciolac, Grigoraș Dinicu, were actually among the most cosmopolitan subjects of the Romanian principalities, invited to the imperial courts, to the aristo salons from Moscow to London with a detour through Istanbul. We can say that Roma lăutari were Cantemir's transnational agents.

The New Lăutărie of the Balkans

The Balkans can be regarded as a specific case of the outernational condition. A territory to be navigated with an "untempered" map, hiding indistinct borderlines, uncharted intersections, and unwritten histories.

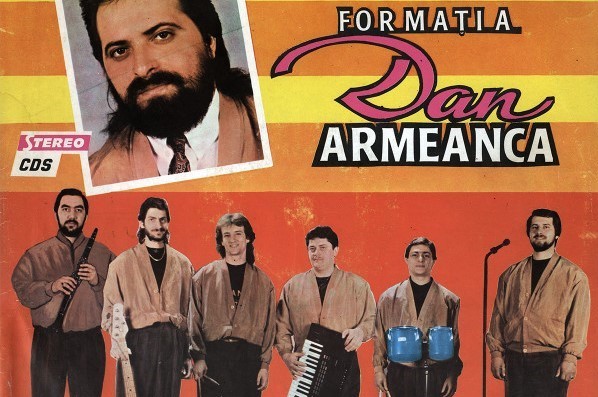

As with many outernational transformations of the last decades in the wedding music of the middle east (Syrian dabke, Kurdish halay, Egyptian chaabi), Dan Armeanca's revolution in the late eighties consisted in electrifying the orchestra, introducing synthesizers, electric guitar and bass, drums, electronic drums and drum machines while radically changing the repertoire. The manea was born (or reborn). .

In the new Dan Armeanca's reiteration, manea meant opening up lăutărie to Turkish arabesque, Greek, Egyptian, and Iraqi electrified disco-pop, but also Western jazz-funk, and to the Balkans in general. The sort of opening that Ivo Papazov made in Bulgaria in the 70s and 80s within Bulgaria's wedding music. In fact, one can argue that Dan Armeanca brought Romania in sync with the Balkans, where in many cases wedding music had already merged with pop (see chalga in Bulgaria, turbofolk in Serbia). Linking Romania to the pan-Balkanic modular station.

(Regarding the modular pan-balkanic station we have to mention that in the late eighties, in parallel with neo-lăutărie, a burgeoning low-fi pop oriental scene was capturing the imagination of the socialist ghetto, with non-roma bands playing a hugely popular Balkan mixture that deserves a simultaneous study. Azur, Albatros, Odeon, Generic were entertaining the working-class irrespective of ethnicity. It was a new genre of party music, it had no tradition, yet it had a lot of appeal. They were playing Romanian music, as well as Serbian, Greek, Turkish, Hindi or Tropical because working-class people parties imposed a playlist “with everything.”)

Futurist features of neo-lăutari (maneliști):

Modular, culturophagic, community based, adaptive, full embracers of technology, genre fusionists, contextual (always context aware).

Although playing often in highly conservative communities, many aspects of Balkans' contemporary lăutari make him/her more in tune with a progressive future than the local Romanian academy. One of the most futuristic features of contemporary neo-lăutari in the Balkans is modularity. Through modus operandi, manele musicians connect multiple worlds, they adapt to and cannibalize (in the sense of Oswald de Andrade's Anthropophagic Manifesto, 1928) different traditions of various ethnicities, informing themselves with mainstream pop and wedding cultures from near-South-East and beyond. Owning the cultural legacy of the Ottoman Empire, the Roma neo-lăutari post-1989 are experts in navigating the germinal border between East and West, acting also as South /North interpreters, masters in cultural trespassing procedures, operating multi-cardinal cultural conversions without prejudice. Always modulating, importing systems from Albania, Bulgaria, while today going global feeding, absorbing reggaeton, cumbia among other genres in their systems.

Dan Armeanca's school of lăutari in the nineties, manelists like Adi Minune, Sorinel Puștiu, Canibalii din Ploiești, Jean de la Craiova, Vali Vijelie, Florin Fermecătorul were (and still are) cultural synthesisers, reading contexts with expertise, constantly updating their repertoire, yet always in an intrinsically democratic spirit: "for everyone."

After three decades, new generations of neo-lăutari and their orchestras have become specialists in keyboards/synthesizers and multiple genres of music. Constantly inventing new "systems" and writing lyrics adequate to new realities, while still performing the community rituals. Using online social platforms with maximum skill. Although many Roma neo-lăutari were already YouTube stars, in the past years manele artists have amassed a massive following in the Tik-Tok Universe, initiating and influencing online trends.

Notwithstanding the forced marginalization of nineties and noughties, in the past 10 years new lăutari like Marius Babanu, Lele, Narcisa, Jador, Bogdan DLP, Leo de la Kuweit, Iuly Neamțu, Tzancă Uraganu' have gradually gained their legitimacy in the Romanian Pop mainstream, piercing local ethnic nationalisms (“Românism”) through talent, groove (balans), knowledge, and swag.

Facing the stigma of regressive elites

Even today, without integrating these realities into a critical history, many academics and intellectuals seem to hold to that post-communist Romanian project that only accepts the romanticized "traditional" type of lăutar, the acoustic "fiddler," without technology, as though the "gagii" (non-roma) want to preserve the 19th century Roma expression; the static(frozen) lăutar, "unable" to develop, to modernize.

For the inter-war generation of right-wing elites, "lăutarismul," articulated by C. Noica (1909 - 1987) who non-factually equates lăutărie with dilettantism, was perceived as the epitome of the south-eastern relativism that contradicts and even becomes the nemesis of the great Romanian cultural project. A national project that is always anti-modern in essence/drive, as it wants to prove/demonstrate a local immobile absolute (the Romanian vital contribution to the international patrimony) only through a non-historical, pre-critical given: "eternity was born in the village," "hill and valley horizon," "don't spoil the corolla of miracles," etc., with all of Lucian Blaga's (1895 - 1961) apophthegms that are essentially forms of the refusal of empirical knowledge and democratic principles, ignoring the critical era and its conclusions that have deconstructed ethno-centrism, monotheism, and monarchy.

After 2000, the new lăutari caused an unprecedented revolt in the intellectual world, with vitriolic public reactions against manele music and musicians. Denoting a thinly veiled racism this defamation campaign was also rooted in another paradoxical rationalization, which although it does not accepts the history of institutional discrimination against Roma, it blames Roma communities of not being "integrated" and "Westernized", and furthermore accusing them of "cocalarizare" (agents of "low-culture"), basically, a menace to the post-communist national project and to society in general.

The Romanian intellectual elites of the recent past never saw cultural value in its wedding music and the Balkans' or Turkish heritage. All aspirations were focused on an idealized West. Refusing to own the Balkans in the body, to get into its groove.

Maqams, Eastern Modes, and Micro-Tones

The versions of Maqam that circulate now in the Balkans have infiltrated for millennia through several routes, folk and cult ones, weddings (and other family events) and the Byzantine Greek church. One can hear oriental micro-tonal inflections (commascommasComma (koma gr. piece, cut, comma) is an interval smaller than the semitone and belongs to untempered systems. Commas are known as the most distinctive feature of Middle Eastern music.) not only at weddings and parties where manele musicians play, but also in Romanian Orthodox' (B.O.R.) churches and chapels where choirs of young Seminarians, taught at theological institutes, perform liturgical scores.

The modal scales used in wedding (folk) and religious (cult) music can shift and re-structure endlessly in the south-eastern territories of Europe, disregarding Christian or Muslim affiliation. Within these low-defined, grey areas Balkan neo-lăutari are most adept. In the last 30 years they have become experts in modulating south-eastern kits of sonic patterns, storing on their keyboards sound banks that can be found and overlap with the ones used at weddings in Syria, along the Middle East, detour through Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan (mugham), Armenia to Bulgaria, Serbia, Macedonia and Romania.

By using the pitch bender to produce makam's micro-intervals (or inter-sound distances, as many Near Southeast schools call them) manele musicians resonate transnationally across and beyond the Balkans.

RESOURCES

History of the Gypsies in Bulgaria and in Europe: Roma - Shakir M. Pashov, 1957.

Balkan Popular Culture and the Ottoman Ecumene. Music, Image, and Regional Political Discourse. Edited by Donna A. Buchanan, 2007

Les manele, symbole de la «decadence » - Speranța Rădulescu, Victor Stoichiță, 2009.

Music and dance of pan-Balkan (and Mediterranean) fusion: the case of the Romanian manea - Anca Giurchescu, Speranta Rădulescu (2011)

The Polyphonic Search for Authenticity in a Balkan Country - Claudiu Oancea, 2020.

Musics of the new times - Romanian manele and Armenian rabiz as icons of post-communist changes. Victor A. Stoichiță, Estelle Amy de La Bretèque. Biliarsky Ivan, Cristea Ovidiu. The Balkans and the Caucasus. Parallel processes on the opposite sides of the Black Sea, Cambridge Scholars, Publishing, 2012.

Manele Music Volume 1: A Rigorously Speculative Email Exchange - Ion Dumitrescu & Paul Breazu, 2016