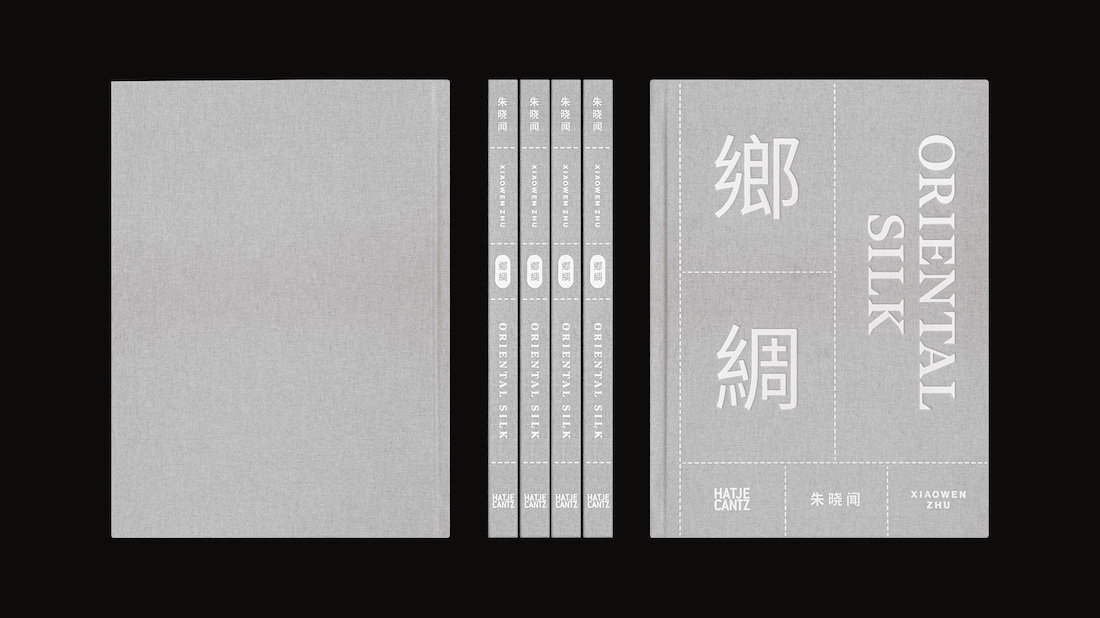

Published by Hatje Cantz

Translated by Nicky Harman

English, Chinese

2020. 196 pp., 51 ills.

ISBN 978-3-7757-4785-1

Artist and writer Zhu Xiaowen is the author of Oriental Silk, a documentary and a book. They are dedicated to an eponymous emporium, the first Chinese silk importing business on the West Coast of the United States since China’s Cultural Revolution. In an essay for EastEast, Zhu Xiaowen talk about her work and the meaning of Chinese silks to one immigrant family’s emotional past.

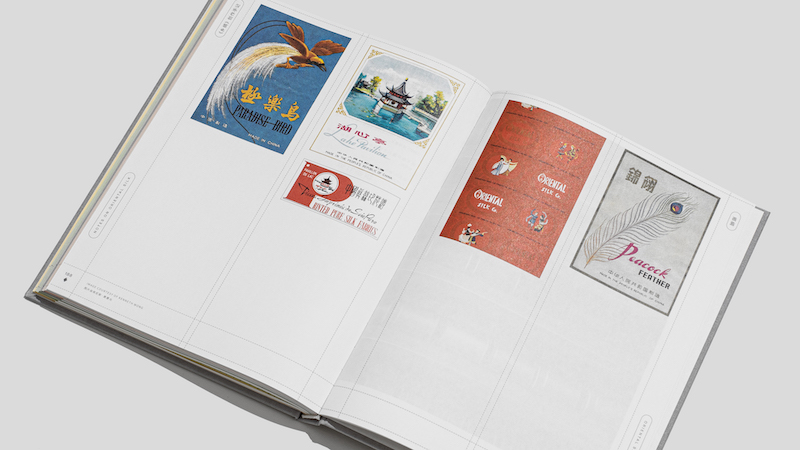

Oriental Silk 乡绸 is the English and Chinese bilingual book deriving from my long-term project of the same title, which is about touch and tactility, craft and value, and the colors of memory. The Oriental Silk emporium, located in Los Angeles, is the first Chinese silk importing business on the West Coast of the United States since China’s Cultural RevolutionCultural RevolutionIn my project synopsis, it states that Oriental Silk is the first Chinese silk importing business in the United States since WWII, according to Kenneth Wong’s oral history, which is open for interpretation. Since the shop was established in the early 1970s during the Cultural Revolution in China when official trading between China and the US did not exist, I chose this time frame for the article to be on the safe side. . Having once risen within the Hollywood movie industry, the shop, established more than four decades ago, has become a productive place to reflect on the astonishing histories of twentieth-century migration and to critique the fragility of the American dream.

Chinese readers can tell that the pronunciation of the Chinese title 乡绸 (xiāng chóu), meaning “silk from the (home)town,” is the same as 乡愁, which stands for nostalgia or homesickness. For me, the craftsmanship of silk and its timeless beauty represent generations of human pursuits that link people and places across time and borders, the meaning of which is particularly relevant to our current reality of physical isolation and distances. Through considered and nuanced documentation of Kenneth Wong, the shop owner’s oral history, my creation attempts to interweave moving images and texts, colors and textures, memories and interpretations, inspired by how personal history is narrated by feelings, instead of fact sheets. Thus, Oriental Silk 乡绸 does not only tell the story of a Chinese-American migrant (Kenneth’s father) fighting in WWII on the European front, who diced with death but returned to America, and eventually became a successful business owner in Los Angeles, but also looks macro at micro, through one family’s legacy and hardship, to scrutinize the intergenerational influence of cross-border cultural heritage.

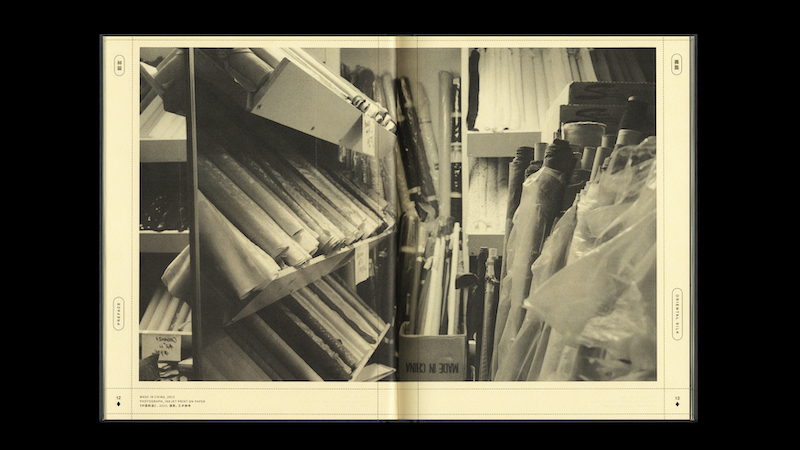

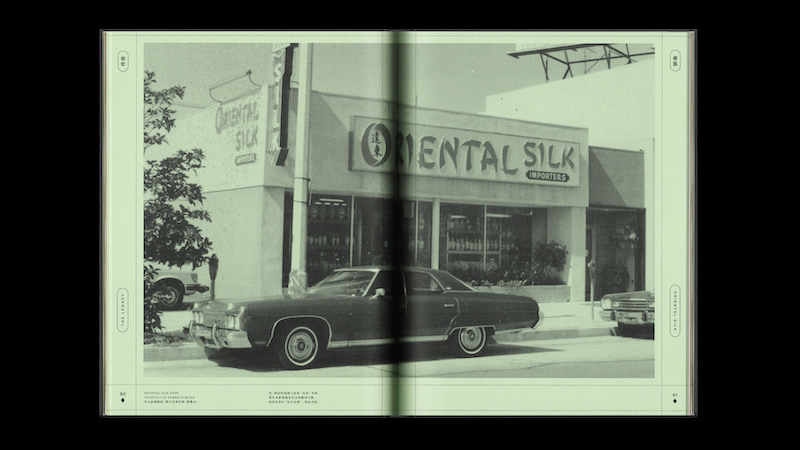

How I came across Oriental Silk is a pure fluke. Between 2012 and 2014, I lived and worked in Los Angeles as an artist-in-residence supported by the Marylyn-Ginsburg-Klaus Fellowship. One day, I was driving on Beverly Boulevard and was startled to see an enormous, somewhat tatty shop sign, across which marched the following message written in the iconic Wonton fontWonton fontWonton, also known as chopstick font. It was originally designed in the early twentieth century with a visual style intended to express “Asianness” or “Chineseness.”: “ORIENTAL SILK Importers.” What looked like something from a bygone age soon transported me back to my memory of Shanghai in the 1990s, when my mother used to take me to the state-run Silk Emporium on West Nanjing Road to pick out fabrics. Inside Oriental Silk, the first thing that assailed my senses was not the glittering display of goods, but a mellow odor that only old shops have:

It is not a perfume, as there is nothing intoxicating about it. Rather, it is the smell of dust-covered, rusted Chinese medicine cabinets in an antiques shop; it is the smell of dogeared, worm-eaten pages of yellow paper, their string binding coming loose, in a second-hand bookstore. But in this unassuming silk shop, it was like the smell of an old woman’s camphorwood trousseau chest stored in the attic and filled with bridal brocades and jewelry that only rarely see the light of daydayZHU Xiaowen, Oriental Silk (Hatje Cantz: 2020), 21..

It was the beginning of my relationship with Oriental Silk—a shop that sold beautiful silk and had served as a magnet to Hollywood’s showbiz celebrities, aristocrats, and the wealthy from all over the world as well as famous designers and big manufacturers. However, it was only through Kenneth Wong’s narrative did I get introduced to this rich yet quiet world, so quiet that one has to listen attentively and patiently—two qualities more and more rare these days, akin to the disappearing of small, family-run businesses like Oriental Silk.

Kenneth Wong, having inherited modesty and diligence from his parents’ humble background and years of striving, gave up his job as a software engineer to take over the store from them after they retired. An amiable and cultured man, Kenneth was more concerned with ensuring that his store and the goods in it gained the respect they merit than with making money. During the turbulent time following George Floyd’s death in May 2020, the neighboring shop of Oriental Silk was looted with the window smashed. Fortunately, Kenneth sold his business just a month ago to a new owner, who will keep the Oriental Silk trademark and hopefully continue its legacy. I was extremely relieved to know that Kenneth and the shop were both safe. After all, it was established by a couple who survived WWII in China and Europe, discrimination, racism, all kinds of business challenges, and eventually passed the shop on to their child.

Watch the full movie here.

What will happen to Oriental Silk in the future? Five years ago, I was driven by this question to complete the single-channel documentary film, which was premiered at the Aurora Museum in Shanghai. Since then, I have taken the project in various forms, comprising film installation, photography, and textile design, to numerous places in the world, from Shanghai to London, from Los Angeles to Berlin, from New York to Rhode Island. This journey follows my decade-long experience of living in diaspora and the milestone is this publication featuring people, places, conversations, and stories interwoven by the meaning of Chinese silks to one immigrant family’s emotional past.

Dr. Cangbai Wang, a reader in Chinese studies at the University of Westminster, said this during a panel discussion about my work in London:

To me, silk is Mr. Wong himself. I’ve watched the film several times. It’s like him being in his own Chinese universe. His dealing with the buttons, silks, and fabrics are just like recollecting his pieces of memories. He enjoys picking them up, because in this process, he’s trying to record his inconsistent memories in relation to faraway China.

China . . . [The question] is: What is China? How do we define China? Actually, since at least 150 years ago, a lot of Chinese people started moving abroad voluntarily or involuntarily, particularly from the “hometowns” of overseas Chinese, or Qiaoxiang, in Guangdong and Fujian, southern China. Kenneth Wong’s family is from Toisan [Taishan]. Ninety-five percent of the Chinese emigrants from Toisan moved to the United States. It started with the gold rush in California and then the railway construction. After that, they started to run laundries or restaurants. That’s the general story that also applies to Wong’s family, the same trajectory. So the film is not only on immobility, but also on mobility. We start to redefine China based on the connections and interactions between mainland Chinese and overseas Chinese. This film gives us a bigger picture to look atto look atZHU Xiaowen, Oriental Silk (Hatje Cantz: 2020), 154, slightly shortened here..

After living through the unprecedented 2020, we have learned that not only people in movement are diasporic subjects, but also almost everyone—as long as you feel that you belong to different places at the same time, and as long as you are missing places or people hard to reach. In this sense, the past year that I spent on editing and making Oriental Silk 乡绸 is a homage to all those who worry when they can return home, as well as to those who have left everything behind to create a better future for their loved ones.

Homesickness

Is a bolt of beautiful silk.

We are here,

History is therethereZHU Xiaowen, Oriental Silk (Hatje Cantz: 2020), 140..