University of Michigan Clark Library Maps

Our open-call finalist, art historian Bella Radenović tells the story of shifting borders around Kars in northeast Turkey. Her research was inspired by an inconspicuous tailor shop in Tbilisi, where a Kurdish tailor, an Armenian dressmaker, and a Russian seamstress were sharing work and stories. “The Kurd and the Armenian,” writes Bella, “lavished me with their nostalgia-filled tales about their hometown of Kars, famous for the 1921 treaty which established modern borders between Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan.”

There are fewer places in Eurasia as familiar with experiences of shifting borders and displacement as the area around the city of Kars in northeast Turkey. It was several years ago that I first heard of Kars in a bustling tailor shop in Tbilisi, in what must be the most multicultural institution in an otherwise painfully gentrified and chi-chi district of Vake. It so happens that the families of the Yezidi tailor Dato and the Armenian dressmaker Gayane, who I got to know rather well over these years, both hail from Kars. Although born and bred in Soviet Georgia, they share a sense of otherness and nostalgia for their ancestral land. Such wistful ache for a distant time or place one has never been to is characteristic of many displaced communities living across the Caucasus. As someone who specializes in cross-cultural exchange during the medieval period, I cherish the polyphonic quality of Tbilisi’s population and its eclectic architectural history, which includes a late antique Zoroastrian temple, an early twentieth-century synagogue, and a Friday mosque serving both Sunni and Shia communities. In the wake of yet another regional conflict, I am however reminded of the oft-tragic circumstances that have brought about this diversity.

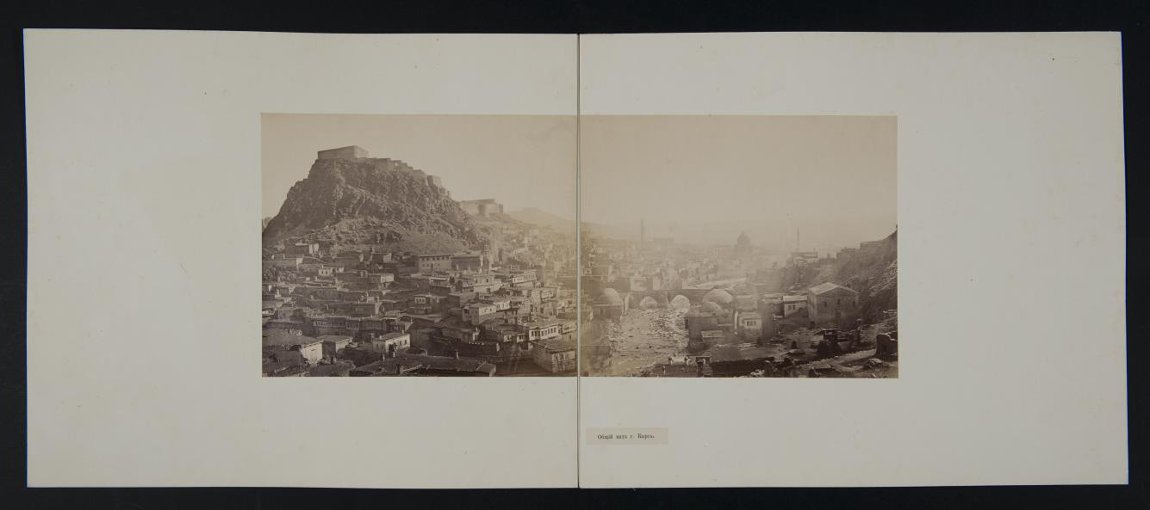

Like nearby Ani, now in ruins but once a bustling medieval city and the capital of the Bagratid Armenian kingdom, Kars has been a borderline from time immemorial. This is in part due to its location on a secluded and high plateau overlooking a ravine, where the plateau of Eastern Anatolia meets the mountains of the Lesser Caucasus. In 1829 Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s best known Romantic writer who was exiled to the Caucasus for writing politically charged and lewd poetry, journeyed from TiflisTiflisName used for Tbilisi during the period when the city was the seat of the Imperial Viceroy of the Russian Empire. to the area, visiting his friends at the Russian military base with the Russo-Turkish War in full swing. In his journal he wrote of his burning wish to set foot on foreign land: galloping towards the border he spurred his horse across it only to learn that it has been recently moved and that he was, in fact, still in Imperial Russia.

Some may recall that Kars is where Orhan Pamuk chose to set his 2002 novel Snow (Kar in Turkish), which explores clashes between different religious and political factions of modern-day Turkey. In the book, the multi-cultural past of sleepy and forlorn Kars, located at the geographical and cultural margins of Turkey, is evoked through images of “old decrepit Russian buildings with stovepipes sticking out of every window” and “the thousand-year-old Armenian church towering over the wood depots and electric generators.” Yet, to many in the region, the city is more familiar through its association with the Treaty of Kars, a 1921 “treaty of friendship” between Turkey and the Transcaucasian republics of Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia, then under Bolshevik control.

Many of the conflicts, hostile attitudes, and territorial disputes that defined the early twentieth history of the region are still far from resolved

Signed in a railway carriage one hundred years ago, the treaty established common borders between the four signatories, “agreeing on the principle of the fraternity of the nations and on the right of the peoples to dispose freely of their destiny.” It came hot on the heels of skirmishes, conflicts, and full-blown wars that erupted in the South Caucasus and eastern Anatolia between the Transcaucasian republics, then briefly independent, and the Turkish National Movement, which emerged after the defeat and subsequent partitioning of the Ottoman Empire in the wake of World War I.

It was thanks to this treaty that Batumi—the city of my birth some thirty years ago—lay within the frontiers of Soviet Georgia rather than Turkey. When in 1921 Turkey ceded the strategic port of Batum and its surrounding area to the Georgian Socialist Republic, it received the areas which it had (re)-captured in the late 1910s, at the time when it was forcefully redefining itself as a single-nation state. Other ceded territories included the southern half of the former Artvin Okrug, once a spiritual and cultural center of medieval Georgia, the former Kars Province, and parts of the Erivan Governate including Mount Ararat, a potent symbol of Armenian identity. Both Georgia and Armenia have deeply cherished memories of the areas lost in accordance with the terms of the 1921 treaty, and there have been several attempts at negotiating border adjustments, all of which to date have failed.

A hundred years on, the demarcations stipulated by the Treaty of Kars are still in place. Yet, many of the conflicts, hostile attitudes, and territorial disputes that defined the early twentieth history of the region are still far from resolved, as demonstrated by the recent war in Nagorno-Karabakh. On maps, borders are demarcated in ways that suggest their unambiguous and fixed status, but the realities of lived experiences on the ground regularly call into question the notions of stability guaranteed by borders, as the anecdote with Pushkin failing to traverse the border cited earlier suggests.

83773/5182, 83773/7245, 83773/7222, 96851/841, 82846/380 / The State Historical Museum of Russia

Today, as in 1921, the Treaty of Kars plays a far greater role in the geopolitical life of the broader region than the city after which it takes its name. Located along the east-west trade routes of Asia Minor, Kars has been home to several cultures and empires throughout its centuries-long history. Although associated with the Armenians, who had inhabited Eastern Anatolia for centuries, Kars has been a battleground for many powers since ancient times and its modern name is believed by some to derive from the Georgian kari, meaning gate or door. In his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, the eighteenth-century English writer Edward Gibbon referred to Kars and its environs as a “theatre of perpetual war.” A sight of much bloodshed and plunder, Kars has been both at the crossroads and at the edges of two seemingly irreconcilable worlds, wedged between the Greco-Roman and later Byzantine world to the west, and the Persian and later Abbasids, Seljuk, and Mongol worlds to the east and south. Although we know from sources that itinerant traders rubbed shoulders with the area’s vibrant Christian and Islamic populations, one inscription from the medieval walls proclaims with open hostility that they had been built “by Christians” and were set up “against foreigners.”

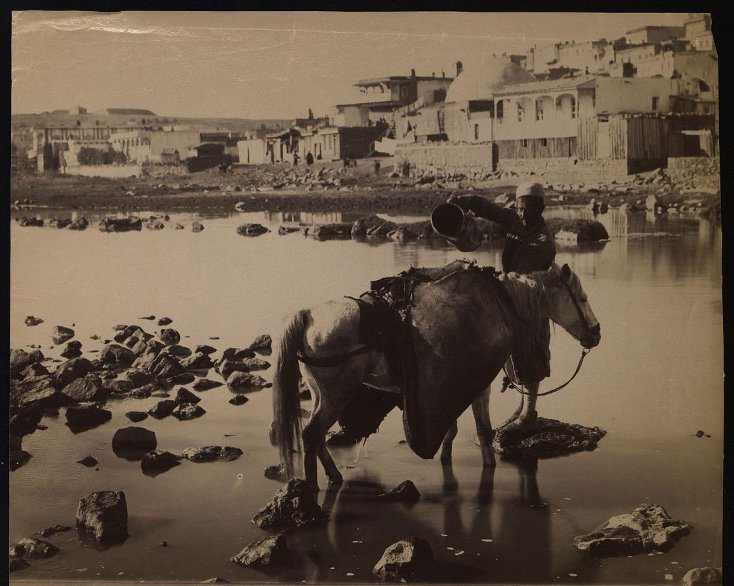

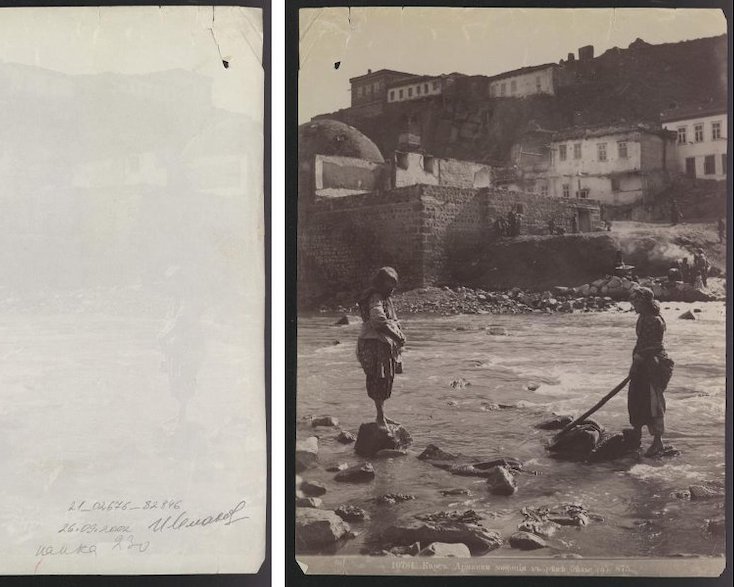

Indeed, Kars had a sizable Christian population throughout its medieval and modern periods, which included Armenians, Greeks, and to a lesser extent Georgians. The tenth century even saw it turn into a center of Bagratid Armenia and become the capital of the Armenian kingdom of Vanand. Less than a century later, however, Kars changed hands to become part of the Byzantine Empire and then the Seljuk Empire, a Turko-Persian Sunni empire. In the early thirteenth century, the joint Armenian and Georgian army gained control of Kars only to lose it to the Mongols in 1242. In the following centuries, Kars continued serving as a battleground for Georgians, Ottomans, Persians, and finally Russians, who captured it during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. This led to the mass migration of the majority of the Turkish population of Kars to the Ottoman Empire and the arrival of Armenians and Greeks from the Ottoman-controlled areas of Anatolia into Kars. Re-captured by Turkish Revolutionaries in 1920 during the Turkish-Armenian War, Kars saw most of its Armenian population driven out for good and a number of its Armenian and Greek churches demolished. Today, the population of Kars is comprised of Turks, Azerbaijanis, and Kurds.

In 2006, Naif Alibeyoglu, a former mayor of Kars, commissioned a thirty meter tall concrete sculpture titled Monument to Humanity as a gesture to promote peace between the people of Turkey and Armenia. Representing two abstracted upright figures reaching to hold the other’s hand, the statue was intended to stand across from the Castle of Kars and be visible from the Armenian border. In 2011, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then Prime Minister, ordered that the nearly completed monument be removed, calling it a “monstrosity.” Despite protests, the sculpture was demolished, crushing with it crucial steps towards the acknowledgement of divisions wrought by territorial disputes and population displacements. I sometimes wonder how different a place Kars would have become if it were not for the consequences of the 1921 treaty.

Ggia / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0