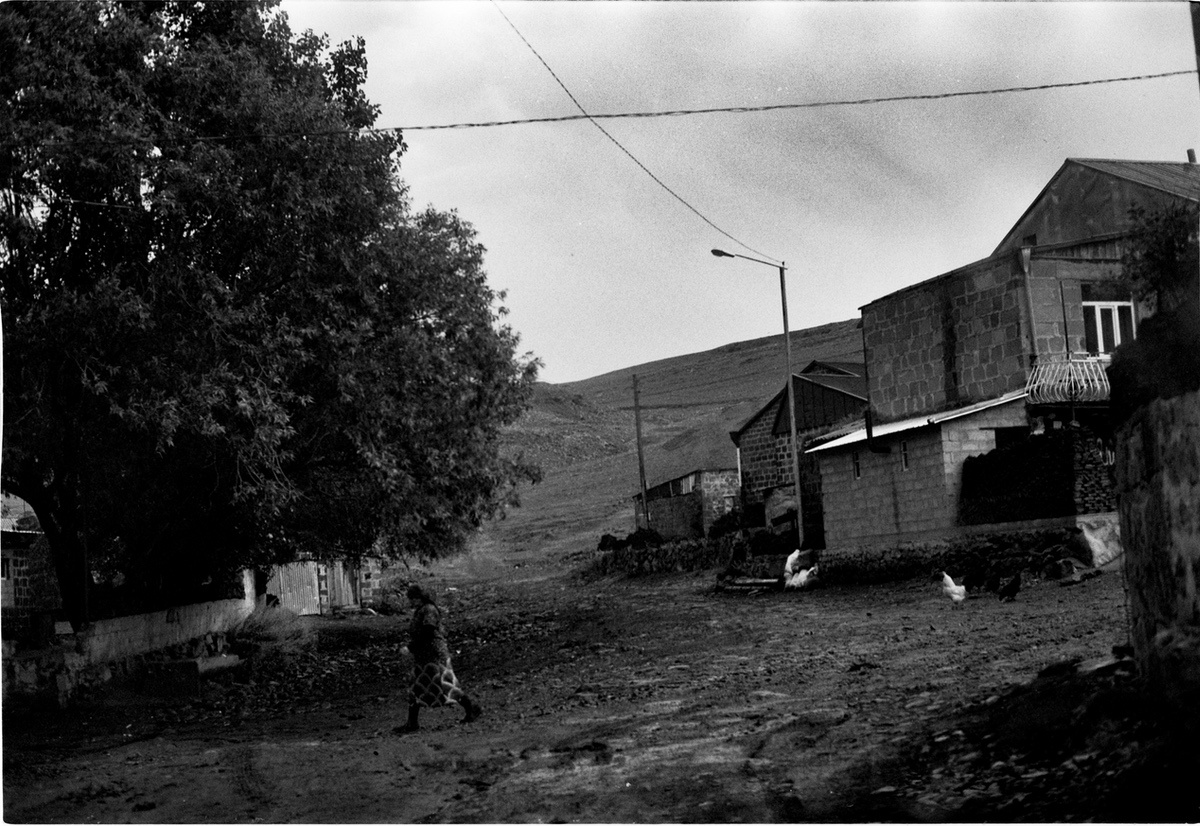

Scott McCulloch, one of the shortlisted finalists of our Dream open call, works with prose, essay, and sound. In the following text, which features his own photos taken in the Javakheti region of southern Georgia, McCulloch writes on the landscape, the everyday, and the intersecting histories of this lesser known corner of the Caucasus.

Passing through the more remote landscapes of Javakheti I cannot see faces as much as the doing of daily life: travelling, fishing, waiting, tanning skins, stacking hay, stacking manure, celebrating a birth, celebrating a marriage, walking the grass and the mud of the hard landscape, crossing the highlands around the lakes, taking brigades of sheep and men and boys on pasture across the highlands, without roads or defined tracks, through the strangeness of being alive. Poka Lake is on the other side of the pass from the last outskirts of Akhalkalaki, a pass with no clear passage, with no road, no sign denoting direction, and no sign of the way across the pasture slopes. No road, no tracks. Axle treads thread through tall white grasses sprouting between rocks and small stones. Hundreds of sheep wander or lie on the slopes to the side of the faint path in the landscape. We pass a large tent made of tarpaulin pulled from truck trailers, erected on the vast plateau pierced by the odd power line standing alien in the otherwise barren terrain of rocks and small stones, of tall white grasses and short green grasses beneath low sky, low-lying and layered with shapeless clouds. A wood stove heats the interior of the shepherd’s tarpaulin shelter. The chimney blows smoke through a slice in the material. The herdsmen pattern their sleep in rotations, two hours in the open each cycle, every night, watching over the lambs, watching over the goats, tending to the dogs, tending to the milking, carrying bread and cheese/flour/dried meat, calling family when the reception intermittently returns on certain peaks in the pass, playing small flutes made of clay or bone to guide the herd—fingers hardened and smeared with wood, grease, brine, butter, ghee, the orange of nylon strings, the rubbing of hands, driving sticks into the earth, making fires, bodies resting in the open. Animal husbandry, agriculture, particularly potato farming, make up the majority of work in the economically stricken region, they say. A good third of the men shift seasonally to Moscow, usually for jobs in construction, usually six to nine months at a time, they say. The closure of the Russian military base in the early 2000s devastated an already stricken economy, they say. A vulture flies for a dead animal nearby. The lake shapes the path ahead. The landscape has little shape without the lakes. Driving over the volcanic range, I feel like I could die in the landscape. An eagle flies overhead in the bright yet sunless sky. Rising a last mound in the highland landscape and turning down into the next valley, Poka village and Poka lake come remotely into view, hanging on the opaque distance, a speck in the ongoing vastness. Bumping and sliding, we descend over rocks and less paths and no road, beside faint treads and footprints and grottoes trailing to the lakes and more nowhere. The landscape is a waiting room: the hole in the circle where our shadows freeze and crack, they say. I look over and watch the lake being kneaded by the winds. The ground before the lake is dug out into holes and pits. Farther down, into the village, warmth flickers in the windows and the damp. Bodies silhouette behind lace curtains. Each dwelling in passing a zoetrope of silhouettes both still and brushing together. Hanging clothes sway between dwellings selling fresh trout and sheep cheese in the faint rain. Tractors and billycarts made of baby car seats and old tyres are left bogged in the puddles and the mud. More faint rain falls, threatening our path forward, bogging our way out, our way of getting out of the territory, out of the highlands and the lowlands, away from the wide lake and its coppery edges, out of Javakhk (Armenian), out of Javakheti (Georgian). Mud flies up from the tyres onto the windows and the sides of the car as we grind into the water table and the small stones, into relics and remnants from the burial mounds and spread of human rash that shaped the lands into where and what they are now. We slip around the earth as the locals laugh and whistle behind lace curtains. Others say the land belongs to others. The air is thick with mist and smoke, the particles of each make veils in the air as if music, vanishing in the air the moment it’s made. Burning manure mixes with frost, vapour, breath. The landscape’s lack of wood sees to dwellings made of manure patties with orange and grey stone, covered in yellow lichens and moss. The chill braces the housing all year, they say. Nothing stops the damp from sliding in, they say. Nothing dries, they say. Flat roofs sprout thick tufts of grass, housing peasants who escaped extinction, housing ghosts of “banditry and separatism” deported to Central Asia in the ‘40s. Deep puddles and fissures cut through the earth, zigzagged and printed with tyre treads and gumboots and animal feet, through fields of storm-tossed rock and bone, through ashcans and crucifixes on windowsills, through a brutal haven of refuge and shelter, through survival. The lake drowned in the Middle Bronze Age, they say, coughing up stone cromlechs on the shores where the cemeteries stand and seep into the ground. For an instant I imagine the distorted smile of a hanged man dangling from the empty stork nest on top of one of the electrical poles that trail down the dirt roads and lanes of Poka. Their prayers have expired, they say. A bell-tower steeple juts from the church’s stone relief sideways, hewn by the winds and time, rashed with frost, spattered with lichens and moss and the rust from the low shore around the lake’s edge. The trout have a special shine on their sides, they say, along with a special taste, they say. The last side of the lake is glacial, an opaque blue fading to farther south. The patterns dissolve in the light. Pelicans, cranes, and storks fly over the seasons of the landscape and its inhabitants. Pre-historic graves dot the south-facing slopes—burial clusters of nomads on the low and high plains—the remains scatter and disperse through the freezing and thawing of glaciers. Out of Javakheti/Javakhk now, we pass a series of what resemble burial mounds (kurgans) as we enter Kvemo Kartli and the Tsalka Plateau. Passing between them patterns the dreaming of the afterlife, the over-and-done-with coming alive, the nomad’s homecoming. Yet there is no road, they say. Just settlement, agriculture, burial, movement. Just stray pieces of life, they say. Stones formed into circles on the eye of the plateaus. The sky slowly sinks. Passing through, the faces keep dissolving in the light, around the lakes that shape and shatter the landscape, through the highlands where the roads barely reach.