Sofya Chibisguleva and Lena Kilina introduce the work of the Mainline Group: an artist collective that doesn’t have to coexist in order to co-create, operating via Zoom, Skype, Twitch, and other media of instant communication. Their pandemic Zoom dream diary titled Chthonian Rehab is available to watch above. Text below was written by Sofya and photos were provided by Lena.

There are the two laws human reality has been obeying and shall continue doing so unless machine learning goes sideways (like in one of David Eagleman’s afterlife talestalesDavid Eagleman, Sum: Forty Tales from the Afterlife, 2009). Whether you are in the Matrix or the Pandemic (or you wish for them to be nested in one other), the stretching of time that dreams provide benefits a productive kind of dissociation—a psychological distancing from our worn out subconscious (newsflash: a woman in Saratov took her iron out for a walk instead of a dog—she failed to distance herself). Dreams give us control when we don't have it or relinquish it when we are overflowing. Either way, we often underestimate the influence that day and nighttime dreams have on us in the post-religious pragmatism of the 21st century. In the meantime, dreams are the real-world stick-shift of the Matrix.

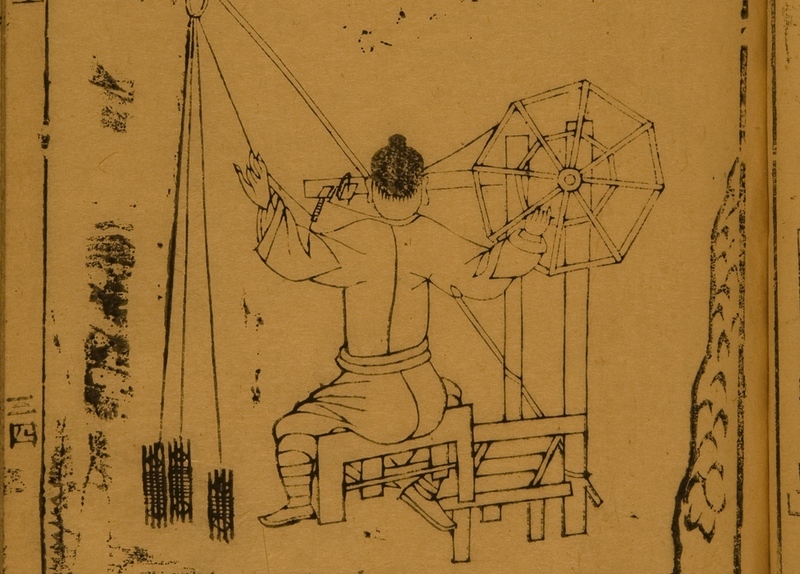

To learn to communicate with our dreams, we must discover the alphabet of our personal unconscious. Unfortunately, there are no textbooks or video tutorials available and the process resembles something of a PhD in psychoanalysis, not a magical spiritual awakening. However, as a result of undying curiosity and unhinged laziness dream mythologies were born. The armies of one's visual, audio, and sensory memories become solidified as bad signs or warnings from spirits. One of the greatest pieces of Eastern Literature is centred around a dream that determines the destiny of a powerful family—Dream of the Red ChamberDream of the Red ChamberDream of the Red Chamber, also called The Story of the Stone, or Hongloumeng, composed by Cao Xueqin in 1791–92, is one of China's Four Great Classical Novels.. In 2020, all of us, including Lena Kilina and myself in the Mainline Group, are dreaming, making plans, and performing life and art from our chambers.

Sometime in April we began seeing dreams of each other and decided to document them. To this day dreams remain one of the lesser-studied areas of human consciousness—both the unconscious state of rest and the wake state of desires and longings. Dreams are where the archaic and the scientific touch and even bridge into one another. They are Möbius-esque spirals of time-consciousness—you can observe Lena's through these film diptychs.

Right: China

Photography by Lena Kilina, 2017-2018

When I came to know Lena in late 2017—who has since joined me as one half of the Mainline Group—she was in Shanghai, wrenching her almost beastful energy into the city like a beetstock—working for a “dream.” In 2020 her entire family is purposefully scattered—Visaginas, Birmingham, herself in São Paulo. We make Zoom performances and the cries of exotic birds disturb our sound checks in Moscow. Long before Lena started singing Russian folk songs with a Capoeira beat, she started her journey to Brazil, then to China, and back to Brazil again. What might seem like a Brownian migration is in fact a result of a dream diffraction.

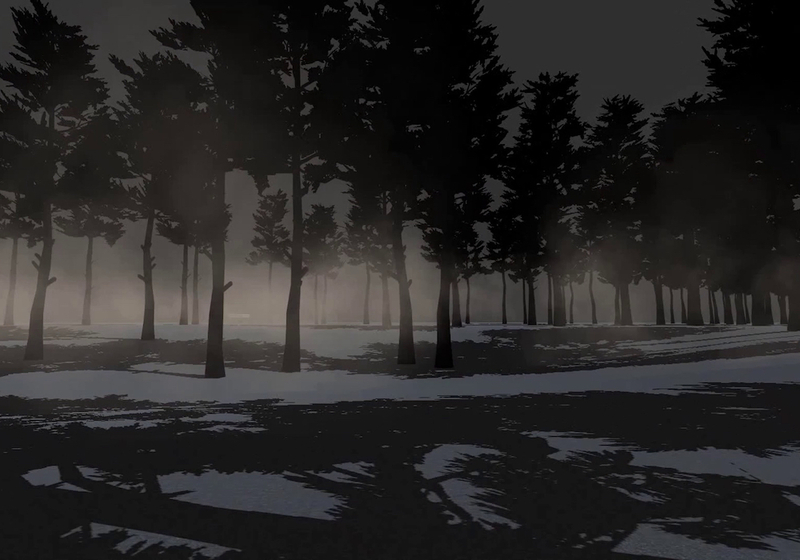

In 1992 she was a child sheltered from the turmoil of the violently disintegrating Soviet Union in a small town on the border of Russia, China, and Mongolia. It belongs to one of those Google Maps destinations that have only pictures of snow. There is an infinite number of shapes that dreams inhabit but at that time Lena Kilina knew only two of them—the sweaty night-time kind and the gazing-at-the-Siberian-sky kind. These dreams would, in time, birth aspirations, longings, calls, wishful thinking, hype and superstition, and, of course, contemporary art.

Even language can dictate the way we strive to achieve our dreams. In Russian, we ”следуем за мечтой,” that is, “we follow the dream”, meanwhile in English—the language of globalisation—the expression is “chase the dream”. While other phrases are possible, of course, the above mentioned forms are a default preset. The Russian version implies that a dream is a tour guide, a leader, a lighthouse, while the English has a strong stench of futility. Dreams do move us forward physically, but do they mentally? The short answer is no. Any expansion from the norm comes at a price of fragmentation. Our own selves fragment, our dreams fragment, our sense of “home” fragments. Moving a profoundly Eastern person like Lena—a Sinologist from Siberia—into the tropical concrete forest of Brazil forewarns of a major psychological shattering. Here is where dreams come to help us reconstruct wholeness or turn into torment that one can't help but contemplate an escape from.

Paradoxically, the escape routes humans tend to choose—like addictions, video games, knitting, painting—are targeted to achieve the same state of bliss and lack of control we get in our sleep, or the opposite state of complete control we get when we daydream. It is a utopia-dystopia balancing act with no East-West meridian, it has its own cultural logic.

Dreams are never a choice between knowing and seeing. The choice is impossible. While Freud described this tug-of-war process “whereby resembling would equal dissembling, and figuring would equal disfiguring,” I prefer Didi-Humerman’s specific commentarycommentaryGeorges Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images, 2005 on dream imagery as the “means of appropriate disfiguration.” Dreams are an enforced rehab, some good, some bad, but nevertheless compulsory.

Right: Brazil

Photography by Lena Kilina, 2017-2018