Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in the Exploration of Central Africa (2000) by the Dutch anthropologist Johannes Fabian describes the methods travelers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries used when producing knowledge about Africa. Nikolai Steblin-Kamensky, Africanist and author of the Tezeta telegram channel, discusses this important work, which calls into question not only the rationality of the researchers themselves, but also the foundations of scientific ethnography, formed under the influence of their heritage.

Working on the book, Johannes Fabian studied the travelogues of Belgian and German explorers—emissaries of colonialism, whose expeditions paved the way for the creation of the infamous Congo Free StateCongo Free StateA state in Central Africa that existed from 1885 to 1908 and was considered the private property of the Belgian king Leopold II. It emerged as a result of the Berlin Conference of 1885, where European authorities discussed their spheres of influence on the African continent. According to some estimates, the Congo Free State had lost between five and fifteen million inhabitants as a result of the introduction of the rigid colonial regime aimed at maximizing rubber production.. Author critically analyzes this legacy—primarily in the form of diaries and published correspondence—showing that often travelers’ achievements were not as outstanding as their contemporaries imagined them to be: the texts contain numerous inaccuracies, mystifications, and speculations. The researcher even doubts some pioneers’ mental health—reminding the reader that those same pioneers found themselves in the conditions of an unusual climate and diseases, consumed large doses of quinine, and were treated with opium-based drugs and strong alcoholic drinksalcoholic drinksJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 67.

. However, Fabian does not aim to present travelers as inconsistent scientists—he problematizes the very idea of the scientific observation of human life and the epistemological attitudes that underlie it, asking: what guided travelers in African studies and how was this reflected in the representation of Africans and, ultimately, in colonial politics?

Fabian's book suggests that in ethnography, fieldwork methods, and textual representations of culture, you can still find traces of the practices that were formed during early expeditions. The pronoun “our” in the title seems appropriate, since readers with field research experience will almost inevitably recognize themselves in some of the book’s characters. The text also reflects the author's rich experience: Fabian has maintained a connection with the Democratic Republic of the Congo since he began working on his dissertation on the Jamaathe JamaaThe Jamaa Movement (which means “family” in Swahili) originated within the Roman Catholic Church in the Congo under the influence of the preaching of the Belgian missionary Placide Tempels, the author of the book Bantu Philosophy (1945). religious movement in the mining towns of the Katanga province, which he defended at the University of Chicago in 1969. His further research in the DRC touched upon contemporary urban culture, theater, and popular painting.

Fabian became famous thanks to another book—Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object published in 1983. Out of Our Minds takes the writer’s ideas that were presented in that earlier work and develops them using concrete historical material: this is a kind of response from Fabian to the accusations that his initial theses were too abstract. In Time and the Other, Fabian wrote that ethnography, while documenting non-European cultures, discursively placed them in a special temporality that did not coincide with that of the writing anthropologist. It is paradoxical taking into account that the very methodology of ethnography is built on common pastime, dialogue, and participation. In constructing the Other by placing him in abstract non-historical temporality, Fabian sees not just an intellectual error or a genre peculiarity, but a political action and ideological basis of colonialism. By creating such an image of the Other, Europeans asserted themselves as the only actors in history and the highest carriers of morality, and in this context colonialism itself became not the seizure of foreign territories and appropriation, but the unfolding of the logic of history and the expansion of civilization.

Time and the Other was written in the wake of postcolonial criticism of ethnography: by the time of its publication, important works of the 1970s such as Reinventing Anthropology by Dell Hymes, Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter by Talal Asad, and Orientalism by Edward Said had already seen the light. The book Time and the Other is connected with the latter in an interesting way: both the authors present their critical analysis of the rhetorical properties of texts and both deconstruct the idea of the Other. Fabian finished his manuscript the same year Orientalism was released, but the book was not published until five years later because four publishers rejected it. It was only on Edward Said’s recommendation that the Columbia University Press gave Fabian a positive answer.

Out of Our Minds continues the epistemological criticism of ethnography, but what is surprising about the book is that the author only interprets and critically comments on travelers’ statements, discovering contradictions and inconsistencies in them. Fabian's attention is particularly focused on those passages where anger, laughter, friendship, eroticism, and irritation could be felt between the lines—in other words, everything that the travelers themselves considered inconsistent with the logic of scientific observation. Fabian argues that such experiences (he proposes to call them “ecstatic”) are key for cognition, however travelers, armed with a positivist concept of science, sought only detached observation. The conflict between ecstatic experience and such rigid attitudes led to actual existential struggles, making the border between madness and rationality more blurred, and the meaning of these words less obvious. Is the white traveler who took part in “wild” dances mad? Is he rational when laughing at an African who has adopted a European style of dress and behavior? Was Frobenius’Frobenius’Leo Frobenius (1873-1938)—German ethnographer, specialist in African art. He took part in twelve expeditions to Africa, the first of which was to the Congo (1904-1906). One of the founders of the idea of cultural circles. mind intact when, giving a farewell to the inhabitants of an African village, he lit fireworks and turned on a phonograph to play Wagner's opera?

Images from: Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, The National Archives UK, Wikimedia Commons

The question of mental health also became the initial incentive for writing the book: while reading Jerome Becker’sJerome Becker’sJérôme Becker (1850–1912)—Belgian traveler, member of International African Association expeditions, and agent of the Congo Free State. He maintained good relationships with Arab traders and did not support the Belgian campaign against the Arabs. He continued traveling with his Arab friends without the support of the authorities. essay “La vie en Afrique,” published in 1887, Fabian wondered if the author was of sound mind, when stating that the vocabulary of an African did not exceed 300-400 words, although in his own text he actually used over 400 Swahili words and about 100 collocationscollocationsJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 2.

. 300 pages of Fabian’s book are dedicated to the description and analysis of similar situations, where the author also questions their status of errors and curiosities and interprets them as a reflection of a systemic epistemological conflict where science, politics, and the daily routine of expeditions were intertwined. Travelers’ scientific views required maintaining distance between them and their surroundings, as well as controlling both themselves and others. They not only considered their caravans as a way of exploring unknown lands, but as a filling in of the political vacuum that they saw as Central Africa. In reality, roads were washed away by rains, porters rioted, guides did not evoke confidence, interpreters pursued their own agenda, and local leaders hindered the advancement of Europeans, rightly suspecting them of a desire to establish trade contacts that bypassed their intermediary interests. But the travelers themselves did not seem to notice this and often attributed their failures to the innate shortcomings of Africans. As a result, their blindness to the real state of affairs and the irritability it generated sometimes resulted in states close to insanity. For example, the head of a German expedition to the Kingdom of LundaKingdom of LundaA political entity with its center in the province of Katanga (today: the Democratic Republic of the Congo), which existed from the middle of the 16th century to 1887.

, Max BuchnerMax BuchnerMax Buchner (1846-1921)—ship’s surgeon, head of the expedition to the Kingdom of Lunda (1878-1881), colonial functionary in Togo and Cameroon. In 1887 he became the curator of the Royal Ethnographic Collections in Munich.

admitted having taken on an uneasy task of recording every single yard of used cloth and every single shot of gunpowder not due to economical reasons, but in order to overcome an obsessive feeling that everyone kept deceiving himdeceiving himJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 185.

.

In such circumstances, an acquaintance with local cultures, customs, and people was often forced, since the expedition’s success was primarily determined by movement in space. So, it was only delays—a constant cause of caravaneers’ irritation—that actually gave researchers a chance to get to know their environment. This knowledge was also forced, as it was not obtained by means of detached observation and mental actions, but through a gradual impact on feelings and attempts to “go beyond oneself”—a process that Fabian defines with the German expression “außer sich seinaußer sich seinJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 8..” To describe these states, the author proposes the epistemological concept of ecstasis. But the ecstatic state should be understood not as an irrational obsession, but rather as a certain quality of interaction, group participation in something on equal terms.

Music is a vivid example of this type of impact, as it creates conditions for overcoming the hierarchical distance inherent in the logic of detached observationobservationJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 109.. In travelogues, music invariably appears as one of the annoying phenomena that cannot be controlled: it is loud, incomprehensible, and irritating. But it is all the more interesting, Fabian notes, to observe some travelers gradually developing an understanding of it. For example, Paul PoggePaul PoggePaul Pogge (1838-1884)—German traveler. In 1875 he went to Lunda as a hunter as part of an expedition, but later led the group. In 1880, he headed an expedition to Lunda with Hermann von Wissmann. He died in Africa from a disease.

started his observations on this topic with the following statement, “Music is very popular among negroes, although one must say that they have no [musical] ear whatsoever.” But soon after he described the emotions of people involved in a dance and the unusual impressions produced by the repetitive call-and-response singing of women who were accompanying the caravan. While getting increasingly interested in local music, the traveler even tried to play the lamellaphonelamellaphoneA name used to describe a number of instruments common in and out of Africa. A lamellaphone is a series of thin plates, each of which is fixed at one end and has the other end free. Pressing the plates with one’s finger or fingernail causes them to vibrate and sound.

himself. His emotions could also be discerned in his description of a ceremony in Musumba, where the residence of the Lunda ruler was located, where he commented on what was happening in the following way, “Although the dance looked wild, one could not say that it was ugly or obscene; on the contrary, the young men swinging green branches showed a good deal of grace. Maybe a European dance teacher could learn some nice new steps from the negroes at MusumbaMusumbaJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 118.

.”

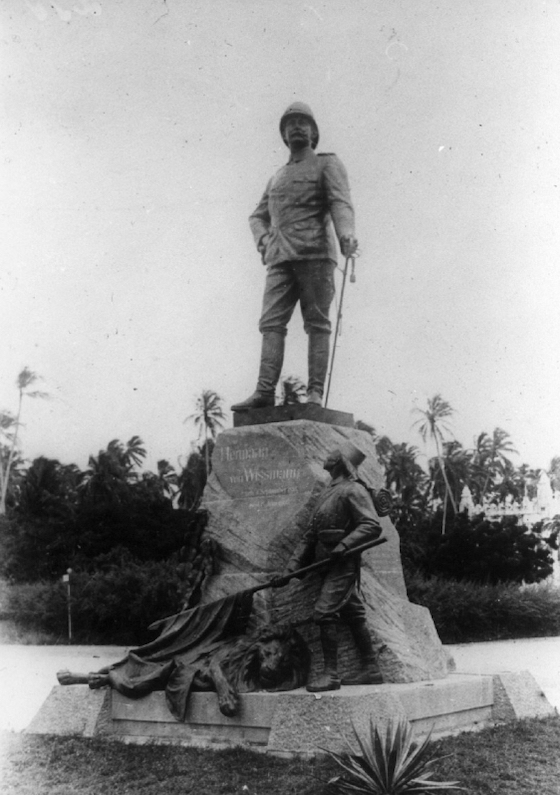

For some travelers, such discoveries were often an insight. They paid attention to the beauty of people, the sharpness of their mind and curiosity, but judgments of this kind were contrary to the expectations and were therefore often leveled by remarks. In this rhetoric, Fabian sees an attempt to maintain distance, hierarchy and, thus, to assert the legitimacy of the colonial project. For example, speaking of MiramboMiramboMirambo (1840-1884)—Nyamwezi warlord, the creator of the largest political association in East Africa in the 19th century. , Hermann von WissmannHermann von WissmannHermann von Wissmann (1853-1905)—a lieutenant of the Prussian army, member of Pogge’s second expedition. He made the first crossing of Africa from west to east in 1880-1883. In 1886, he crossed Africa for the second time. From 1895 to 1896 he was the governor of German East Africa.

noted that he was “bellicose prince who must inspire respect even in a European.” In another example, Camille CoquilhatCamille CoquilhatCamille Coquilhat (1853-1891)—a Belgian lieutenant. He participated in an expedition to the upper reaches of the Congo River in 1882-1885. He made another trip in 1886, and in 1890 took the position of Vice Governor-General of the Congo Free State.

talks about a colorful performance and concludes that it was most likely that “the natives simply imitated one of their numerous superstitious ceremoniesceremoniesJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 123.

,” although other European viewers understood it as a gesture of hospitality and the locals’ witty presentation of their culture. The heuristic component of Coquilhat’s statement is zero, but it is interesting that the traveler considered it important to make it and thus to deny the locals’ ability to be creative.

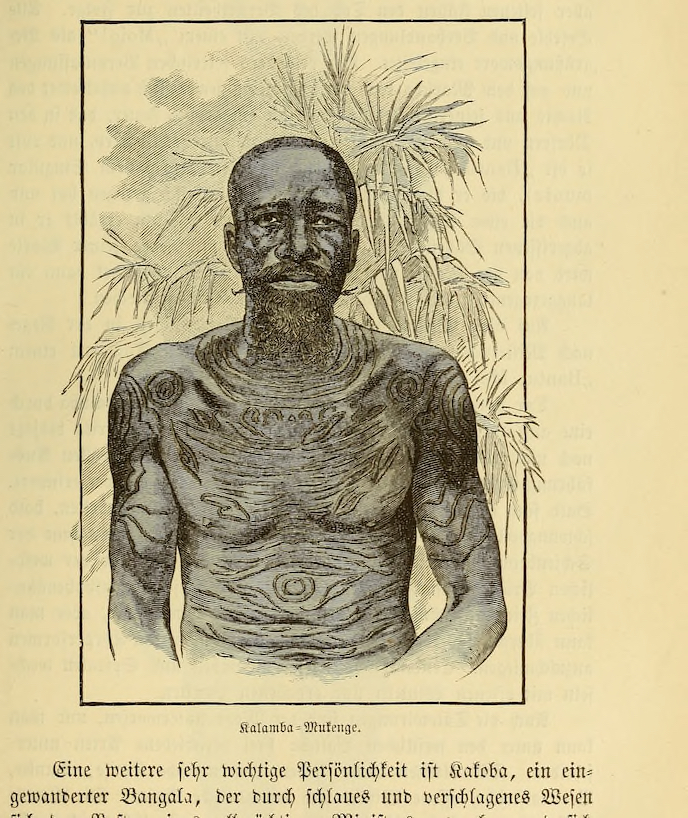

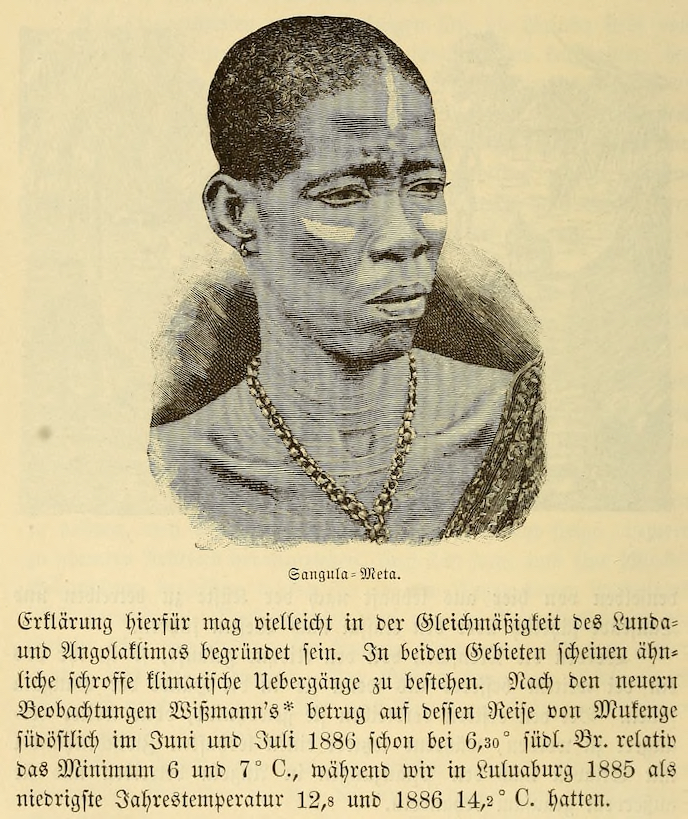

Engravings from Wissmann, H. Im innern Afrikas: die Erforschung des Kassai während der Jahre 1883, 1884 und 1885 (1888).

The book is not built on the study of historical plots, but on the appeal to abstract categories through which Fabian views the study of Africa by Europeans. The chapters are titled “Living and Dying,” “Drives, Emotions and Moods,” “Things, Sounds and Spectacles,” “Presence and Representation,” etc. But one of them stands out from the rest and describes in detail a specific historical episode dedicated to the friendship of the already mentioned Hermann von Wissmann and Paul Pogge with the Bashilange peopleBashilange peopleA subgroup of the Luba people, which in the second half of the 19th century embarked on a path of radical cultural transformations. The Bashilange abandoned the practice of the death penalty and the poison ordeal. The movement overcame the clan system and all of its members called each other brothers and sisters. Old rituals were eradicated in favor of the cannabis cult, and one of the names for the movement was “bene diamba /riamba” (the children of hemp).. Fabian sees this meeting as evidence to the fact that the relationship between the Europeans and Africans could have been very different. The Bashilange’s trust and support shown to the travelers was unprecedented. Their chief Mukenge and his sister Meta, a specialist in rituals, became friends with Wissmann and Pogge. It was only thanks to the Bashilange that Wissmann crossed Africa for the first time from west to east: Mukenge himself and Meta accompanied him to Nyangwe, overcoming more than 500 kilometers. Poggy lived with the Bashilange for over a year—and at the end of 1882 wrote in his diary, “My life here is so beautiful, so pretty, so quiet, so calm; friendly, splendid people, what else do I want.”

However, the charm did not last long: in 1884, Wissmann, with a small group of armed Europeans, supported by Mukenge and Meta, persuaded fifty local leaders to join the union, which later became the basis of the Congo Free State. The traveler himself explained this success as follows, “After all, my strongest support was the trust which the Bashilange had put in me after four years of acquaintance, a trust that must appear miraculous even to someone who knows the negro and which can be explained only by their abnormal intellectual geniusgeniusJohannes Fabian. Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000), 174..” This unthinkable rhetoric, according to Fabian, made it possible not only to instrumentalize friendship, but also to see a manifestation of high intelligence in Mukenge's trust and his willingness to serve the creation of the colony.

Critics note that Fabian's approach is also not devoid of essentialism: he is quite bold in speaking about the “tribe” of travelers-anthropologists, ignoring nuances and the development of research methods. Indeed, Fabian's view of travelers creates a distance and encourages readers’ surprise at their irrationality. But he needs this distance to emphasize the similarity between the researchers and the Other, whom they were creating during the expeditions. Strange African performances can be compared to the pomp of caravans with flags and other European attributes. The fetishism travelers saw in every manifestation of African religiosity reflects their own blind faith in the superiority of the scientific worldview. The conventionality of these generalizations makes readers feel that positivist ethnography only offers them fiction, while the real experience of human interaction is positioned as insignificant. The positive and, perhaps, the central message of the book is related to the fact that with the recognition of the epistemological significance of ecstatic experience, fundamentally different knowledge becomes possible—the knowledge that denies the hierarchy between the researcher and the researched and makes them equal participants of the creation of representation.