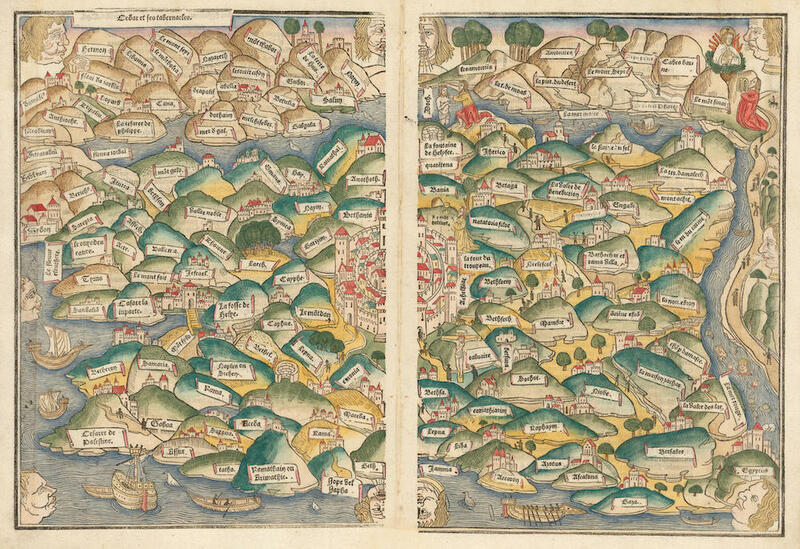

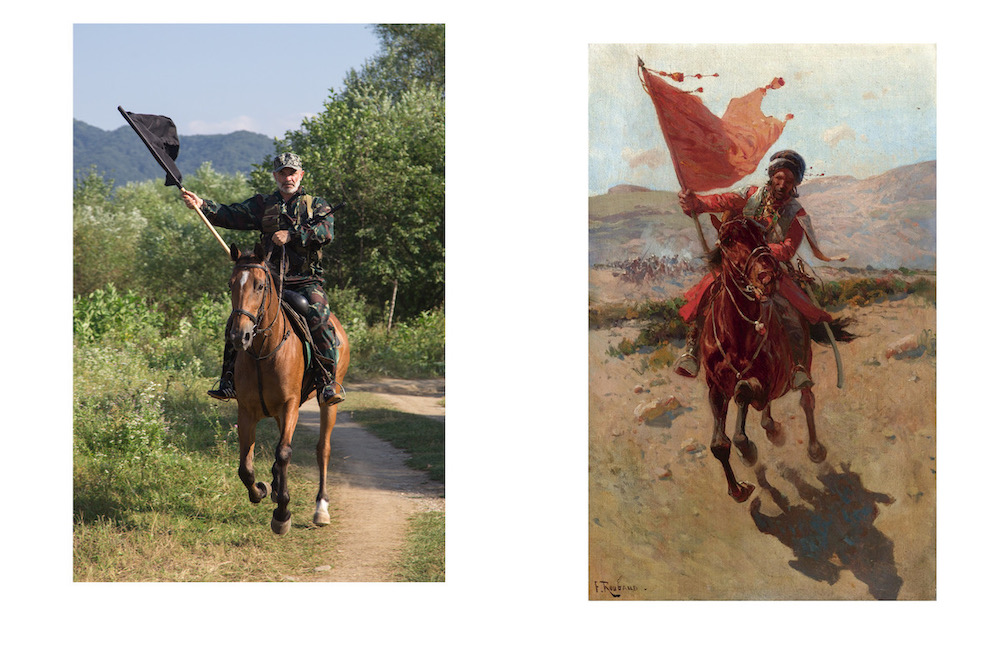

Images are used here and hereafter:

Left: Ilyas Hajji, 2016

Right: paintings by Franz Roubaud

Dagestan is a region with a predominantly Muslim population, annexed to the Orthodox Russian Empire in the second half of the 19th century. For the majority of the population of modern Russia, it falls into the general frame of stereotypes about Muslim regions, while for the rest of the world it does not exist at all, considered just another part of Russia. News from Dagestan often appears in the Russian-language informational space for a variety of reasons. Not infrequently, the analysis of events that take place there is distorted by ingrained stereotypes and ideological simplifications, as well as by a banal lack of knowledge of the region’s history. EastEast editors Nastya Indrikova and Konstantin Koryagin have gathered experts’ comments in order to present a more nuanced picture of life in Dagestan. This first part of our material covers the history of the founding of the Republic, its national hero, the life of its Jewish minority, and the rules that govern everyday life.

Dagestan has never been a state, there has never been such a country. There have been many different feudal entities: the Shamkhalate of Tarkithe Shamkhalate of TarkiThe Shamkhalate of Tarki was a state entity centered around Tarki (now a settlement within modern-day Makhachkala). It included lands located in the southeastern part of modern-day Dagestan. The Shamkhalate was formed on the territory of the Cherkess ulus as a result of the disintegration of the Golden Horde and existed from 1443 to 1867. It was governed by the Kumyk dynasty. While part of the Russian Empire from 1806, it remained a separate territorial entity and was abolished in 1867., the Kazikumukh Khanatethe Kazikumukh KhanateThe Khanate of Kazikumukh was a state formation with a Lak dynasty that existed in the territory of Dagestan during the 8th to 17th centuries. Its capital from the 8th century was Kumukh, renamed to Kazi-Kumukh in the 12th century.

, The Khunzakh KhanateKhunzakh KhanateThe Hunzakh Khanate was a state formation and a military-political alliance that existed from the 12th to the 19th centuries, with its center in the village of Hunzakh. It is another name for the Avar Khanate. Under Umma-Khan, a collection of customs called the "adaat" was created, which served as a code of legal norms in the khanate. Assemblies of representatives of the confederation (rukkel) took place at the congregational mosque of Hunzakh. In 1803, it acknowledged the protectorate of the Russian Empire. During the Russo-Caucasian War, it was partially under the control of Imam Shamil and partially governed by the Russian Empire.

, and so on. Alongside these, there have been unions of free societies of the Greek polis type, where one settlement or union of settlements called itself a state. In Turkic, “Dagestan” means “country of mountains.” Today, of course, Dagestan covers not just mountainous, but also flat territory. At the end of the Caucasian WarCaucasian WarCaucasian War was a long-term series of military actions (1818–64) between the Russian Imperial Army and the native inhabitants (Adyghe, Abaza–Abkhaz, Ubykhs, Vaynakhs, and Dagestanis) of the North Caucasus which resulted in the Russian annexation of the Caucasus and the ethnic cleansing of Circassians. The Dagestan-based Caucasian Imamate waged jihad against Russia from 1829 to 1859, when Imam Shamil surrendered. In 1864, Russia abolished the Avar Khanate. Between 1864 and 1867, the Russian Empire organised the mass deportation of the Circassian inhabitants from the subjugated lands after that the displaced people were settled primarily in the Ottoman Empire.

(1817–1864), a number of oblasts were established in the Caucasus, and Dagestan ended up as part of the so-called Dagestan oblast. The borders of this region shifted often, especially after the revolution in Russiarevolution in RussiaRevolution in Russia, or the Russian Revolution, is a common term to refer to the period of mass political and social change in the Russian Empire starting in 1917. This period is connected to abolishing the monarchy, dissolution of the empire, and adopting a socialist government. The core events are represented by two successive revolutions (revolution in February of 1917 and revolution in October of 1917 respectively) and a bloody Civil war.

. During the Civil WarCivil WarCivil War in Russia is a name for a multi-party civil war (1917 - 1923) in the former Russian empire sparked after the October Revolution. Additionally to Red Army of Bolsheviks and so-called White movement of anti-socialist forces, the Civil war was accompanied by foreign interventions (Britain, France, Germany, and others) and the broad resistance of local combatants.

, from 1917 to 1921, there was the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus. In 1921, the Dagestan SSR was formed, and it also constantly changed its borders. For example, in 1938, the Kizlyar and Achikulak okrugs okrugs A type of administrative division in some Slavic-speaking states

were joined with Stavropol, before being returned to Dagestan in 1958.

The conversation about supra-ethnic identity, about “Dagestanis,” came about quite late. Previously, people had thought in terms of territories and administrative divisions. At first, they thought in terms of free societies, like the Karata peopleKarata peopleThe Karata Free Society was a union of linguistically and ethnically related rural communities in western Dagestan, centered around the village of Karata. It also included the jamaats (administrative units) of the settlements of Anchih, Archo, Rachabolda, Mashdada, Upper Ilhelo, Alak, Heleturi, and Siukh., or in terms of states, like the Khunzakh Khanate, or such supra-ethnic structures as the Imamate of Shamilthe Imamate of ShamilThe Imamate of Shamil refers to the North Caucasus Imamate during the rule of Imam Shamil (1834-1859). During Shamil's tenure, the North Caucasus Imamate operated under a codified set of laws based on Sharia called the Nizam-i Shamil.

. Later, they thought in terms of okrugs and administrative areas, which also did not reflect ethnic divisions. Up until the revolution, there was no talk of ethnic groups, and the first Imperial Census of 1897 was conducted in terms of religion and language. It was only in Soviet times that the Dagestanis began to form as a kind of community—as an ethnic group they appeared with the first Soviet census of 1926.

With time, people began to think of themselves as Dagestanis and to perceive others in the same way. An ideological construct began to live its own life. “Dagestanis,” like Yeltsin’s “RussiansRussiansRussians is a word with multiple connotations deeply rooted in the colonial narrative of Russain Federation history. Within the Russian language, there are two commonly used Russian words that are translated into English as "Russians". One is 'Russkiye' which most often means "ethnic Russians". Another is 'rossiyane' which signifies "Russian citizens" or individuals holding Russian passports irrespective of their of ethnicity, religion, language, and place of inhabitance. In everyday discourse, 'Russkie' might be a tool to highlight the difference between Muscovites (inhabitants of Moscow, the metropolitan city of the Russian Federation) and the diverse groups of population conquered in different centuries by Russian state. ,” comprise many different elements—this is an supra-ethnic umbrella term. Since 2003, a holiday has existed intended to commemorate the formation of Dagestan as a nation, the “Day of the Unity of the Peoples of Dagestan,” a celebration of the victory over the warriors of Nader Shah that takes place on the 15th of September. The holiday is based on the idea that alongside ethnic groups—Dargins, Avars, Laks, Kumyks, and others—there is a more important community, the Dagestanis.

Even if we take a separate ethnic group, for example, the Avars, we will find it to contain many subdivisions. In 1926, during the first Soviet census, the Avars considered themselves separate peoples—AndiansAndiansThe Andis are a local group within the Avar community, defining the speakers of the Andi language. Historically, their settlements are located on the southern slopes of the Andi Ridge, along the left tributaries of the Andiyskoye Koysu River. The ethnonym is derived from the name of the largest settlement in the community - the settlement of Andi - in the Botlikh district of the Republic of Dagestan., BotlichsBotlichsThe Botlikhs are a local group within the Avar community, defining the speakers of the Botlikh language. Their historical settlement area includes the villages of Botlikh, Miarsa, and Ashino in the Botlikh district, as well as Batlakhatli in the Tsumadinsky district of the Republic of Dagestan.

, KaratinsKaratinsThe Karata people are a local group within the Avar community, identifying the speakers of the Karatin language. Their historical settlement area includes the villages of Karata, Anchikh, Tsumali, Archo, Nizhnee Inkhello, Verkhnee Inkhello, Mashtada, Ratsitl, Rachabulda, and Tukita in the Akhvakh district, as well as Nizhnee Ikhwelo in the Botlikh district of the Republic of Dagestan.

, and so on. These were the terms with which they answered the question “Who are you?” Of course, they did not have the concept of an “ethnic group.” They had not attended the courses in Ethnography at Leningrad University that would have allowed them to think in terms of ethnic categories, but they were able to define themselves through locality and language. Later, they would be united into the Avars by the 1959 census—in contrast, the Lezgin, for example, preserved a significant separation—the AghulsAghulsThe Aguls are a local group within the Lezgin community, defining the speakers of the Agul language, which belongs to the Lezgin group of the Nakh-Dagestan family of Northeast Caucasian languages. The ethnonym originates from the name of the gorge Agul-dere (Агъул-дере). Historically, their settlements are located in the Agulsky and Kurakhsky districts of the Republic of Dagestan.

, TsaTsaThe Tsakhurs are a local group of speakers of the Tsakhur language within the Lezgin group of the Nakh-Dagestan family of Northeast Caucasian languages. The ethnonym originates from the name of the settlement Tsakhur. Historically, Tsakhur settlements are located in the Rutulsky district of the Republic of Dagestan, where they occupy the high-mountain zone and the headwaters of the Samur River, as well as on the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Range, in other words, in the foothill and plain settlements of the Zaqatala and Qakh districts of Azerbaijan.

khurskhursThe Tsakhurs are a local group of speakers of the Tsakhur language within the Lezgin group of the Nakh-Dagestan family of Northeast Caucasian languages. The ethnonym originates from the name of the settlement Tsakhur. Historically, Tsakhur settlements are located in the Rutulsky district of the Republic of Dagestan, where they occupy the high-mountain zone and the headwaters of the Samur River, as well as on the southern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Range, in other words, in the foothill and plain settlements of the Zaqatala and Qakh districts of Azerbaijan.

, and RutulsRutulsThe Rutuls are a local group, identified as speakers of the Rutul language within the Lezgin group of the Nakh-Dagestan family of North Caucasian languages. The ethnonym is derived from the name of the village of Rutul. Historically, Rutul villages are located in the Rutul, Akhtyn, Babayurt, and Kizlyar districts of the Republic of Dagestan, as well as in the Sheki and Gakh districts of Azerbaijan.

were not included among them. Despite the fact that in the post-Soviet period, many people began to strive for clarification of their identities, the state was nevertheless able to have things as it wanted: the majority of smaller groups consider themselves Avars. If you ask them: “What ethnicity are you?” they answer: “I am an Avar,” but then specify: “I am an Avar, but I am ChumalalChumalalThe Chamalals are a local group within the Avar community, identifying the speakers of the Chamalal language. Historically, they compactly inhabited the villages of Tsumada, Upper and Lower Gakvari, Gigatli, Gadiri, Agvali, Richaganikh, Egdada, Gachitli, Gigatli-Urukh, Batlakhatli, Tsundi, Urguda, Tsidatl, Arkaskent, and Tsumada-Urukh in the Tsumadinsky district of the Republic of Dagestan.

,” or “I am an Avar, but I am Andean.” Their languages and elements of their cultures differ, which is why they are separate identities, albeit of a lesser order. That is, you can at once be an Andean, and an Avar, and a Dagestani, it is a multiple identity.

The world is very complex, there can be many identities. This is important. In Dagestan, people understand this perfectly

It is difficult for the tourists from central Russiatourists from central RussiaLocals in Dagestan referring to Russian tourists usually mean the population of the Russian Federation's regions beyond the scope of the North Caucasus. who travel to Dagestan to understand this fragmentation and multilingualism. The majority of the world is bilingual or polylingual, but Russians are a more or less homogenous group, an exception to the rule. They are monolinguals, people who speak only one language, people who don’t even have significantly differing dialects. There are many of these people, more than 100 million, but they have a single identity. An Andean knows the Avar language because they learned it at school as a mother tongue. They knows some Kumyk, because their sister married a Kumyk. They know Russian, and they learned Arabic at the madrasamadrasaMedrese (or madrasah) meaning “the place where lessons are given”, is an educational institution in Islamic societies.

. The world is very complex, there can be many identities, this is important. In Dagestan, people understand this perfectly. Here is one settlement—one language. This is a unique set of circumstances even in comparison with the other republics of the North Caucasus. For example, in Chechnya and Ingushetia, the majority of people know their language and speak it, but in Dagestan, all you have to do is go down to the plain and you will encounter problems. If you want to communicate with others, you speak in Russian. This is why Russians are comfortable in Makhachkala, where Russian is now undoubtedly the lingua franca. Previously, Turkic languages had served as the lingua franca, such as Azerbaijani and Kumyk. The main criterion of ethnicity is self-determination and self-consciousness. Not appearance, not culture, not even language.

Ekaterina Kapustina — Candidate of Historical Sciences, Lead Researcher, Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the RAS (Kunstkamera)

Imam Shamil is the national hero of the peoples of Dagestan and a prominent historical personality, but, more than anything else, he was a religious figure. The movement led by Shamil was, by definition, jihad. “The Struggle for Faith in the Path of Allah” (Arabic jihad) was waged for a quarter of a century by three Dagestani imams—Ghazi Muhammad (1829–1832), Gamzat-bek (1832–1834), and Shamil (1834–1859). The movement involved military action to defend Islam against not just “infidel” Russians but their allies among the local Muslims who had resisted the imposition of Sharia law in their territories. From the time of Imam Ghazi Muhammad’s call to fight the “kafirkafirKyafir (sometimes spelled "kafir") is an Arabic word used in Islam to refer to a non-believer or someone who rejects the faith or teachings of Islam. It's often translated as "infidel" or "disbeliever.",” “munafiqmunafiqMunafiq is an Arabic word used in Islam to define a hypocrite who, while not being a believer, pretends to be a Muslim in public.

,” and “apostates” in 1830 until the last days of the Caucasian Imamate, little changed. Shamil called Dagestan a “house of war” [Arabic dar al-harb] between Muslims and infidels, and, according to him, an apostate of the fate was “he who bowed to the infidel enemy, or ran to him, or lived under his rule, although he would be a Muslim by religion.” This definition was disputed by many ulama in Dagestan, which cast the legitimacy of Shamil’s jihad under doubt. On the August 25th, 1859, with the capture of Imam Shamil at Gunib, the Imamate of Chechnya and Dagestan, which in Soviet and post-Soviet historiography would be variously termed the “theocratical rule of Shamil,” the “movement of the Highlanders under the leadership of Shamil,” and the “state created by jihad” ceased to exist. The Caucasian War had had come to an end.

Over a hundred years of Soviet-Russian rule, the image of Imam Shamil has turned into a very convenient and effective means of manipulating public consciousness. Soviet historiography presented different images of Shamil on society. From the 1920s to the first half of the 1930s, the concept of “national liberation movements” came into academic circulation, and the imams who had led the resistance of the Highlanders were termed “representatives of the interests of the vast working and exploited masses.” At the same time, the state atheism of those years required that historians come to terms with the religious component of the movement, which they prudently termed “reactionary.”

At the beginning of the 1950s, the idea of the supposedly voluntary entry of “national peripheries” into the Russian Empire and the progressive significance of this became a central tenet of the social class theory conception of liberation movements. This idea was aimed at the official policy of the friendship of the peoples of the USSR. The attitude to Imam Shamil changed fundamentally. He was suddenly exposed as a religious fanatic, as a British, Iranian, and Turkish mercenary. The Highlanders’ resistance to the Imperial Russian Army during the Caucasian War was deemed fanatical, fired by Muslim clergy and Turkish agents.

This was when Rasul Gamzatov’s poem “Imam” appeared, in which Gamzatov called Shamil a “traitor of the people,” a “Chechen wolf,” and an “Ingush snake.” Later, the poet admitted:

The poem Imam is a shameful black mark on my conscience, an incurable wound in my heart and an unrightable mistake in my life. Because of it, I am ashamed . . . to look into the eyes of my mother. The poem was written in my youth under the influence of the “agitmassagitmassAgitmass is an abbreviation for Department for Agitation and Mass Campaigns in the USSR. Additionally to the name of the organisation, it might be understood as an overall term covering numerous state-lead activities for intentional, vigorous promulgation of socialist propaganda” works of those times.

From the middle of the 1960s until the second half of the 1980s, priority in academia began to be given to study of the progressive significance of the consequences of the integration of the North Caucasus into the Russian Empire.

The post-Soviet period brought liberation from old ideological restrictions, but, as the last two decades have shown, full-fledged academic analyses of the history of the integration of the North Caucasus into the Russian Empire have not appeared. Studies have been marked by excessive politicization and a biased treatment of sources that resembles socio-political journalism. Modern historiography of the Caucasian War has proved incapable of answering a number of questions about the military-political and military-religious history of Dagestan in the first half of the nineteenth century. It has been unable to emerge from crisis, remaining captive to Soviet cliches about the voluntary integration of the peoples of the North Caucasus into the Russian Empire, of the friendship of the peoples of Russia and the Caucasus, of anti-feudalism, of national liberation movements, and of the resistance of freedom-loving Highlanders to colonial enslavement.

Over a hundred years of Soviet-Russian rule, the image of Imam Shamil has turned into a very convenient and effective means of manipulating public consciousness

An eloquent example of how they continue to try to manipulate public consciousness with the name of Imam Shamil today is the work of the Shamil Foundation cultural-historical society. The cultural-historical society spreads yet another ideological conception of Shamil—anti-scientific, but corresponding to the “challenges” of modern times. Their main thesis is that Shamil’s primary achievement was the civilised unification of the Caucasus with the Russian Empire on the basis of mutual respect, mutual enrichment of cultures, and a truly fraternal union of peoples. According to the statements of the Shamil Foundation, Shamil preached ideas of unification for the sake of peace in our land, making an invaluable contribution to both the strengthening of mutual understanding between Muslims and Orthodox Christians and to supporting the official status of Islam and defending its traditional values. Decades later, the Shamil Foundation resurrects the very cliches from with Independent Researchers in Post-Soviet Russia had tried to move away from with such difficulty.

The different inventions required by different times and dictated by ideological circumstances finally confused everyone regarding real historical figure—only myths have remained, and among these one can find any Imam Shamil for any purpose—a hero or a traitor, a democrat or a religious fanatic. Much is known about him, but do people want to know the historical truth about him? As my experience has shown, people categorically, even aggressively, do not want to know, not wanting to part with the convenient, simple myths that they have so gotten used to over the last thirty years.

Patimat Takhnaeva — Candidate of Historical Sciences, Senior Researcher at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences

When people talk about Adat or Sharia law being used as a legal system in the North Caucasus, they do often fully understand both what they are talking about, nor how it all functions.

Adat is the customary law of the Caucasian peoples. Most often, people who say that living according to the Adats live according to uncodified norms, that is, according to customary law (“as it was with our elders”), which is a highly mobile structure. For this reason, when someone says “It is Adat,” we never really know exactly what that person means—certain norms that have taken root in this society? Or a more precise concept, related to notes in the margins of the Koran in this particular village? Or perhaps they mean the codified Adat of free societies that were written down in the nineteenth century, according to which one had to hand over a certain number of bulls for murder, another for abduction?

It is the same with Sharia. Sharia is a legislative legal system. Within it, different legal schools (madhabs) exist. These schools propose different interpretations of holy texts, of the Koran or of the Hadith. In order to live according to Sharia law, one has to live in a Sharia state, where Sharia is state law, that is, the system. As in any state, one needs specialists and functionaries—legal scholars, Sharia judges and lawyers, the institutions themselves, and so on. Otherwise, as in Dagestan, your Imam might have had three years of education in a madrasa, or he might have studied for fifteen years in Syria or Egypt. They will have different competencies—one will have fragmentary knowledge, the other systematic knowledge, received through a university education.

In the context of the North Caucasian ImamateNorth Caucasian ImamateThe North Caucasus Imamate was a theocratic state entity that existed from 1829 to 1859, encompassing Dagestan, Chechnya, and Circassia in military opposition to the Russian Empire. It was a union of numerous free societies united under the authority of elected imams, who were Gazimukhammad (1829-1832), Gamzat-bek (1832-1834), and Shamil (1834-1859)., which existed until the entry of Dagestan into the Russian Empire, the imposition of Sharia was successful in some places, in others it wasn’t. The Imamate was a very volatile structure. One day, you would have an imamate in your village, the following day, regular imperial troops would have come in, and the Imamate would have ended. After the end of the Caucasian War, the Military–Public AdministrationMilitary–Public AdministrationVoenno-Narodnoe Upravlenie, or Military-Popular administration, is a form of colonial rule which the Russian Empire used to govern the conquered population of the Northern and South Caucasus and the Central Asia. This system of colonial administration maintained a clear separation between a lower ‘native’ level and an upper, executive level manned exclusively by Russian army officers seconded from military service. According to historian Michael Kemper, the colonial authorities believed that the maintenance of Adat law (customary law) in the rural areal would be necessary in opposition to Islamic law (Sharia) 'which in turn had been promoted by the great North Caucasian insurgencies under Shamil and other Imams'.

was established in the oblast. On the one hand, this was external imperial control. On the other, they tried to play with local laws—this was necessary for the codification and administration of the region. There were qadis in the villages, and in some places they tried to introduce Sharia norms. But what kind of Sharia can we talk about in the twentieth century? In the 1930s, they burnt Korans across Dagestan and repressed the mullahs. In Soviet times, Sharia had almost no chance of survival, though certain elements were preserved through the norms of customary law.

No community in Russia can live solely according to Sharia law, as Russian state law must also be followed

It is wrong to say that Sharia returned with the emergence of religious freedom in the post-Soviet period. It would be more correct to speak of polyjuridism, in which state law, local Adat, and Sharia are used at the same time. Sharia here is one of the systems available to people to use voluntarily under certain circumstances and only on certain matters. There are legal spheres that most often use Sharia law—family and marriage relations, property disputes, and pre-trial reconciliations, but only when this is possible. If something is a criminal offence under the law of the Russian Federation, no one in our state will allow you to make peace and hand over ten bulls. Even if you have reconciled under Sharia, you will still be sent to prison. But in cases with debts and creditors, you can go to an imam. The imam will be your qadi, your Sharia judge. Let's take Muslim marriage as another example. In the case of divorce, you also go to the imam. The imam divorces you and orders you to give your wife a certain amount of real estate and income, because that’s what Sharia says. But you don’t want to do this. What next? Officially, according to state law, you and this woman are not married, you don’t have a stamp in your passport. You don’t even necessarily have to go to court given that, officially, she is no one to you. If you call an opponent to a Sharia court, the authority of your group should be important to him. If, for example, he is a God-fearing person and you live in the same village and know each other well, then there is a high chance that he will agree. But if he is from a different area and doesn’t know anyone from yours, he might answer: “Go to the civil court.” No community in Russia can live solely according to Sharia law, as Russian state law must also be followed. In fact, some Sharia norms are just the good will of people to not use the state power in the resolution of conflict.

Ekaterina Kapustina — Candidate of Historical Sciences, Lead Researcher, Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Kunstkamera)

The history of the appearance of Jewish communities in the Eastern Caucasus is one of the most difficult and complicated issues in modern Caucasian studies. For whatever reasons discussion of the provenance of the diaspora in this region arises, it inevitably begins with these questions: when, and from where?

The development of the diaspora was the result of constant migration over many centuries, driven as much by change in political systems and inter-state conflicting decrees as by personal convictions. The Jewish people who arrived from the south of the Caspian Sea speaking an Iranian dialect only received the epithet “mountain” from the Russian administration in the second half of the nineteenth century: this was when the self-designations of “Juhuri” (Jew) and “Juhuri dogi” (Mountain Jew) circulating in the region were legitimized at state level. These particular differences in self-definition were based on regional characteristics and “different models of ethnic identityidentityKupovetsky M. G., On the historical demography of ethno-territorial groups of mountain Jews of Azerbaijan, p. 145..”

For centuries, Middle Persian remained the main language of communication for both the Jews and the Tatsthe TatsUnder the name 'Tats', one can refer to a specific ethnic group and communities speaking the Tat language, which was widely spread in the Caucasus region. Up to the 20th century it was used by both Muslim communities and non-Muslim groups such as Mountain Jews, some Armenians, and the Udins. During the Soviet era, the seld-identification as 'Tat' began to be accepted among Mountain Jews intelligentsia for various reasons. of the Caspian Caucasus. There was an Iranian-language written tradition that used Hebrew graphics. Modern ethnographic and epigraphic studies in an ethnocultural sense have shown that the Jews of the mountains of the Eastern Caucasus were, at the start of the nineteenth century, still a part of the world of Iranian Jewry, with which they retained quite close contacts until the integration of the Eastern Caucasus into Russian EmpireRussian EmpireKupovetsky M., Jews of Kakheti in the XIV–XVII centuries, pp. 32–33

.

From observations made over the course of epigraphic investigationsinvestigationsSystematic epigraphic research into historical Jewish cemeteries began in 1991 and continues today. It was initiated by the Institute of Archeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Azerbaijan SSR and is now overseen by the Museum of the History of Religion of Saint Petersburg, the Sefer Scientific and Humanitarian Center, and the Dagestan Scientific Center., one can conclude that the center of Jewish settlement was south and central DagestanDagestanCherny I., Mountain Jews of the Terek region // Caucasian Mountain Jews, (Moscow: Tsentrpoligraf, 2017), pp. 7–62; Anisimov I., Caucasian Jewish Highlanders // Caucasian Jewish Highlanders, p. 161.

. This region can also be considered as the historically most probable route for the movement of communities from Karabakh and Shamakhi to Derbent. By the nineteenth century, the Jewish population in Dagestan was located primarily in rural areasareasThere were Jewish quarters in the villages of Imam-kuli-kent, Mamrach, Khosh-Memzil, Arag, and Khanjalkala. In Tabasaran, there were quarters in Maraga, Heli-Penjik, Karchag, Dzherakh; in Kaitage, there were quarter in Majalis and Yangikent; in the Tarkov territory`–in Andirei, Aksai, Kostek and Tarki, Khasavyurt, Kizlyar; in the Derbent possession, in Rukel and Aglabi, in central Dagestan, in Sergokala, Dorgeli. The villages of Abasavo and Selakh, near Khuchni, Nyugdi-Myushkur were entirely Jewish.

.

According to the accounts of the Jewish explorers and travelers Judas Cherny (nineteenth century) and Ilya Anisimov (twentieth century), whose main subject of study became the religion and rituals of the Mountain Jews, Mountain Jews lived in large familiesfamiliesCherny I., Mountain Jews of the Terek region // Caucasian Mountain Jews, (Moscow: Tsentrpoligraf, 2017), pp. 7–62; Anisimov I., Caucasian Jewish Highlanders // Caucasian Jewish Highlanders, p. 161.. Their descriptions of everyday life make it possible to reconstruct the operation of religious and Adat lawslawsLocal laws based on the customs of Kunakism and blood libels.

in Jewish families. One family included three to four generations and could number up to seventy people, who would live together in one courtyard. Several large families descending from a common ancestor formed a “tukhumtukhumTukhum is a form of kinship community, each of which trace their lineage back to an actual or legendary ancestor and inhabit a particular area in Dagestan.

” (literally—seedseedLevirate marriage is a form of polygamy.

). In the cities, Jews lived in separate quarters or suburbs. The community was led by the head of the most respected or most numerous family, and the chief rabbi of the city was chosen by the leaders of the community. Otherwise, the Juhuri culture did not significantly differ from the culture of the Dagestanis or the Azerbaijanis: they prepared the same dishes from Caucasian cuisine, danced the same Lezginka, dressed similarlysimilarlyAlbum of the Caucasus. Souvenir du Caucase (Kislovodsk: Publication of T-va F. Aleksandrovich and K, 1900. Phototype “Mountain Jew”.

. It was also customary for them to pay a kalymkalymKalym is a word of Turkic origin to define the bride price typically provided in the financial or labor form by the groom's side.

and to arrange betrothals in infancy. Mountain Jews were fully integrated into the complex structure of inter-tribal relations in the Caucasus, and they still have a reverent attitude to their fellow countrymen to this day. They were known as “brave horsemen,” though at the same time, they always observed the Sabbath, the rite of circumcision, and ate only kosher foodfoodPeoples and religions of the world: Encyclopedia, chief editor V. A. Tishkov. Editorial team: O. Yu. Artemova, S. A. Arutyunov, A. N. Kozhanovsky, V. M. Makarevich (deputy chief editor), V. A. Popov, P. I. Puchkov (deputy chief editor), G. Yu. Sitnyansky. Moscow: Great Russian Encyclopedia, 1998), URL: https://nazaccent.ru/nations/gosky_jew/ (access date: 01/16/2021).

.

Judas Cherny and Ilya Anisimov also described the funeral rites of the Mountain Jews, and the picture they provide is supplemented by cemeteries and tombstones with epitaph textsepitaph textsEpitaphs are sayings composed to mark a person's death and inscribed on tombstones.. Although Jewish cemeteries have not survived to our day in all villages, those that have give us a very broad idea of the geography of the settlement of the Jewish diaspora and indicate the close contacts of Jewish families with local populations. For example, Jews who had just moved from the mountain village of Abasavo to Derbent at the beginning of the nineteenth century volunteered en masse to join the detachments defending the new state border in 1832: the Russian one.

Mountain Jews were fully integrated into the complex structure of inter-tribal relations in the Caucasus, and they still have a reverent attitude to their fellow countrymen to this day

Over the course of the long Caucasian War (1817–1864), Jewish families were in the same position as the other inhabitants of the villages targeted by raids. The fate of the village of Dzherakh, where the population was mixed, is indicative: in 1843 it was attacked by Hadji Murad’s battalionattacked by Hadji Murad’s battalionThe attacks by Hadji Murat's detachment refer to one of the events during the Russo-Caucasian War (1817-1864). Hadji Murat was an Avar military leader, deputy, and ally of Imam Shamil. In some sources, it is mentioned that in 1843, Abdullah-bek's detachment, another military leader of Imam Shamil, also abducted part of the population of the Jewish quarter of the settlement of Jerakh., and combat-ready Jewish men joined the ranks of the defenders of the village (tombstone inscriptions testify to this conflict). Persecution forced Mountain Jews to move under the protection of either Turkic (Derbent, Quba) or Russian (Nalchik, Kizlyar, Grozny) fortresses. The Caucasian War diluted the Jewish communities of Dagestan with Ashkenazi Jews who served in the Russian army. These were the original communities of Temir-Khan-Shura/Buynaksk and Petrovsk/Makhachkala.

In the last years of the Russian Empire, pogroms and blood libelsblood libelsBlood libel is a murder accusation claiming that representatives of various ethnoreligious minorities sacrifice people and/or use human blood to perform cult rituals. Throughout time, blood libels targeted communities of the early Christians, German colonists and different groups of Indigenous populations colonised by the Russian Empire. began to be recorded. A number of tombstones included information about pogroms, about Jews having been killed by goyim (non-Jews). But tsarism cannot be solely blamed for this: the Caucasian Jews did not fall under the discriminatory Russian legislation on Jews. It is most likely that what ethnologists and sociologists call everyday antisemitism had a place here. The change in the composition of the Jewish community (the influx of AshkenazisAshkenazisAshkenazi Jews are one of the Jewish diasporic groups that massively resided in Central and Eastern Europe until the mid of the 20th century.

) also played its role, as well as the active inclusion of the region in the political and economic life of the Russian Empire. Mountain Jews often suffered from pogroms during the Russian Civil War (1918–1922). Many settlements were massacred. At the same time, one of the tombstones in the Jewish cemetery of the village of Arag (the village of Ashaga-Arag was entirely Jewish) from the beginning of the twentieth century (1914) carries a dual-language inscription in which the second language is Lezgin, and the Lezgin-language inscription is in Cyrillic characters. Today, this fact is relevant to both general and particular understanding of those invisible threads that interweave the cultures, languages, and social traditions of neighboring peoples in Dagestan, of the processes that might be defined as close, reciprocal contacts.

Everyday antisemitism was not eradicated during the Soviet period. In August of 1960, a newspaper article titled “Without God is a Wide Road” by D. Makhmudov was published in Buynaksk. The article stated that Jews were buying 5/10 grams of Muslim blood, diluting it with water in large buckets, and selling it to other Jews. The contents of this article were broadcast on local radio. It almost ended in a pogrom. The Jews of Buynaksk went all the way to the Politburo. Moscow was forced to intervene to defuse the situation.

According to the information of Valery Dymshits, a famous ethnographer and social scientist who was one of the first to respond to the riots at Makhachkala Airport on October 29, 2023, the Jews of Dagestan and Kabarda were subjected to violent pressure in the 1990s (threats, abductions, murder), as a result of which they were forced to flee their homes and apartments, often leaving everything behind. There are currently 3 families left in Nyugdi, as it became clear to me over the course of ethnographic work, the communities of Jankent and Majalis disappeared for the same reason. The multi-family communities of Buynaksk (5 families lived there in 2020), of Makhachkala, of Kizlyar, and of Khasavyurt disappeared at some point. The Jewish population of Derbent has decreased from 17 to 2 thousand. Jews have fled/migrated to Israel, Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Rostov-on-Don, Stavropol, and Pyatigorsk.

The surviving Jewish communities in Dagestan did not expect the events of the 29th October, 2023. Along with V. Dymshits, I see a possible reason for what happened in the inability of the authorities to resolve current and long-standing urban economic problems and the local conflicts that have arisen due to the resettling of Makhachkala. If the Mountain Jews are forced to flee the Caucasus after these events, this will mark the final collapse of their diaspora as a distinct culture.

Natalia Kashovskaya — Museum of the History of Religion, Head of the Eastern Religions Department, Saint Petersburg

Katya Dikova, Nastya Indrikova, Konstantin Koryagin and Maria Vyatchina compiled the material. Translation of notes by Maria Vyatchina. Translation from Russian to English by Charlotte Neve.