Photos by Mitya Lyalin

The Yerevan-based Library for Architecture is a place for the professional architecture community to engage in dialogue and consider new architectural strategies. EastEast asked its 12 co-founders to each choose a building in Armenia that they find particularly significant and to explain their choice. The result is a multifaceted collection that introduces critical examples and incorporates a variety of approaches and considerations.

Since its beginning, modernist architecture has been defined by a universalist and internationalist perspective: the refusal of local specifics and an embrace of functionalism and “cutting-edge technologies.” These theoretical foundations did not always work in practice. Instead of proving functional, they often promoted superficial and colonial interests. Gradually, these ideas began to change: from the 1950’s, Soviet modernism began to incorporate elements of national art and the culture of the Soviet republics. It is possible to say, following Leon Krier, that by the late eighties the modernist architecture had suffered a gradual collapse of its founding principles and shifted to a pluralism with greater sensibility for vernacular architectural forms and sustainable construction methods. Armenia is a vivid example of this process: having suffered the powerful influence of Soviet modernism, in the 1990’s the country faced a new quest for identities, architecture being one among many others.

The selection below shows the incredible variation in forms and principles that have informed the architectural landscape of Armenia throughout its more recent history.

TL Bureau | BUS STATION, HRAZDAN

The bus station built in 1978 by Henrich Arakelyan was supposed to be the gate into the splendid new life of the young industrial and then burgeoning town of Hrazdan. Thanks to its daring shapes, from the beginning the station stood out from the uniform mass of gray housing, run-of-the-mill schools, and administrative buildings. Today, when most of the town’s landscape is dilapidated, the bus station looks even more unique or even alien-like; the only difference is that today it is a symbol of decay and broken dreams. The bus station fell into ruin during the 1990’s. In 2002 it was privatized and is now used as an event hall; it is under risk of being demolished.

Hayk Zalibekyan

Bus Station in Hrazdan. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

SNKH

It might be an obvious choice, but if we’re to choose only one project, the first one that pops up in mind is Moscow Cinema Theatre Open Air Hall. Both emotionally and professionally, we feel connected to it. For us, it is the architectural embodiment of 60’s thaw and optimism. Unfortunately, our generation of millennials didn’t get a chance to witness its glory. We inherited its demise, apathy, and the threat of demolition.

Ashot and Armine Snkhchyan

Moscow Cinema Theatre Open Air Hall. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Moscow Cinema Theatre Open Air Hall. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Moscow Cinema Theatre Open Air Hall. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Moscow Cinema Theatre Open Air Hall. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Moscow Cinema Theatre Open Air Hall. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

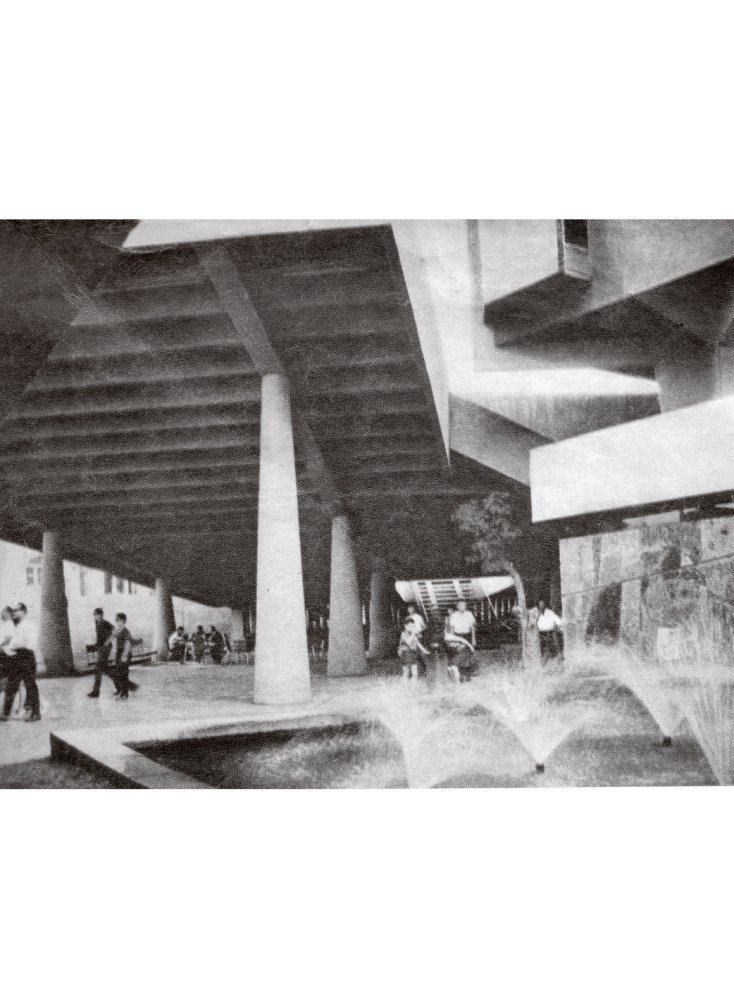

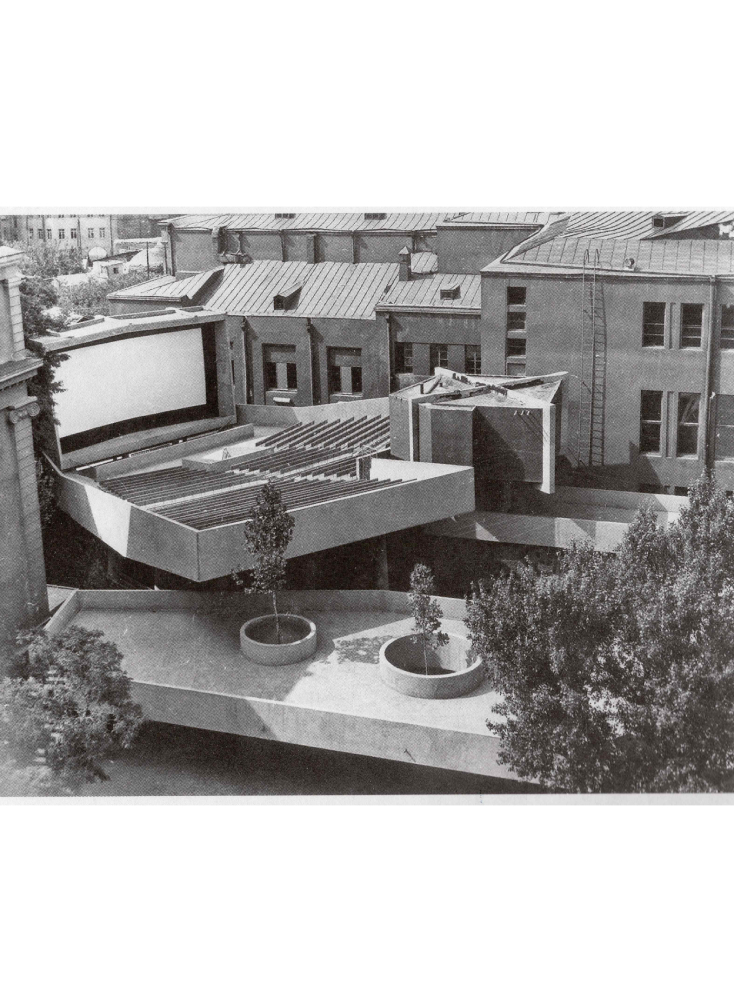

Archive photo. Year Unknown

Ruben Arevshatyan Archive, architectuul.com / CC BY-SA

Archive photo. Year Unknown

Ruben Arevshatyan Archive, architectuul.com / CC BY-SA

Moscow Cinema Theatre. Exterior. Exterior. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Moscow Cinema Theatre. Exterior. Interior. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

auditoria |

This house is immediately recognizable on Isakov Avenue. This house does not require descriptions; it itself is a text, a large, charming text in several languages, instantly communicating and remaining at a distance. Suspended between unfinished and abandoned, filled with details and incompleteness, it seems to contain a reflection of all the active forces of Armenian architecture. For its properties of advanced craftsmanship and theoretical fullness, I think this house is important for our collection.

Alexey Lashkov

Admiral Isakov Avenue 26 in Yerevan. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Electric Architects |

It happens that we are more impressed not so much by accomplished architectural masterpieces as by unfinished ones which have fascinating hidden potential architects detect. Architectural artifacts from the Soviet past can be considered not only as a burden of a long-gone era, but also as something that can be reinterpreted into something new. The Sanatorium Complex of Soviet Armenia on the shores of Lake Sevan is one of these incomplete architectural ensembles. Geometrically simple, but effective under the dazzling sun, its facade element creates a laconic and at the same time dynamic image of a honeycomb, a kind of “health factory.”

Tigran Gevorgyan

Sanatorium Complex at Lake Sevan.

Photos by Electric Architects

Storaket | ARARAT CINEMA, YEREVAN

Opened in 1974, the movie theater was a multifunctional complex, which consisted of three main parts: two drums of different sizes, but with the same mold, extending above the edges, and an open area under the halls, where exhibition halls, a cafe, a bar, and ticket offices are located. The interesting thing is that the "Rossia" cinema was built in the place of the famous historical market and in independent Armenia, that huge theater was turned back into a market.

"Ararat" Cinema. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

"Rossia" cinema. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Meganom | RESIDENTIAL BUILDINGS IN DILIJAN AND TAKHTA

It seems to us at that the preservation of Kond (a historical neighborhood in Yerevan), research and development of villages, communities, and practices of self-governance, and the creation of modest-scale projects and inventory entities, along with special attention to the small-scale architecture, can be an alternative to large scale and “expensive” architecture. Using these optics, the window-hole punched by the resident students in the Dilijan architectural residence seems a rather significant piece of architecture.

Yury Grigoryan

Residential building in Takhta

Photo by Alexey Lashkov

Residential building in Dilijan, 2023

Photo by Mitya Lyalin

Residential building in Dilijan, 2023

Photo by Mitya Lyalin

Residential building in Dilijan, 2023

Photo by Mitya Lyalin

Tarberak

Milimetrovka was built in 1966 by Architects L. Gevorkyan and D. Torosyan. If this building grabs someone’s attention, it is certainly not for its aesthetic appeal or interesting architectural solutions. It expressively and genuinely explains Yerevan by reflecting individual characters, attitudes, and circumstances of a sizeable population sample. There is only a handful of buildings as open and honest as Millimetrovka.

Karen Berberyan

Milimetrovka. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

STOHA (on behalf of NPATAK) | CHARLES AZNAVOUR SQUARE, YEREVAN

Сonsidering architecture as a dialogue of presence and absence, when asked to highlight a significant building in the context of our current lives and the city we live in, we consciously choose absence—a public piazza, where people pause from an infinitely fast way of living, allowing themselves to breathe and feel engaged in the surroundings. One such location that stands out as a rare void in Yerevan is Charles Aznavour Square—a small, human-scaled, and modest yet generous urban square, hosting ultra-diverse flows and gatherings.

Arineh Keshishi

Charles Aznavour Square. March 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

Karen Balyan

Zvartnots is the most avant-garde construction in classical Armenian architecture. It is also mythical—the cathedral was built and then demolished twice. Recreated by Toros Toromanyan, the mythical image of Zvartnots became the prototype for the National Theatre building of Alexander Tamanyan, the new avant-garde. Later, the cathedral again inspired the creation of another avant-garde building, the airport. That is to say, Zvartnots is the symbol of everything new.

Karen Balyan

Zvartnots Cathedral, 2022

Aleksey Chalabyan / Wikimedia Commons

Ruins of the Zvartnots Cathedral, 2014

Marcin Konsek / Wikimedia Commons

Ruins of the Zvartnots Cathedral, 2010

Shaun Dunphy / Wikimedia Commons

Ruins of the Zvartnots Cathedral, 2010

Shaun Dunphy / Wikimedia Commons

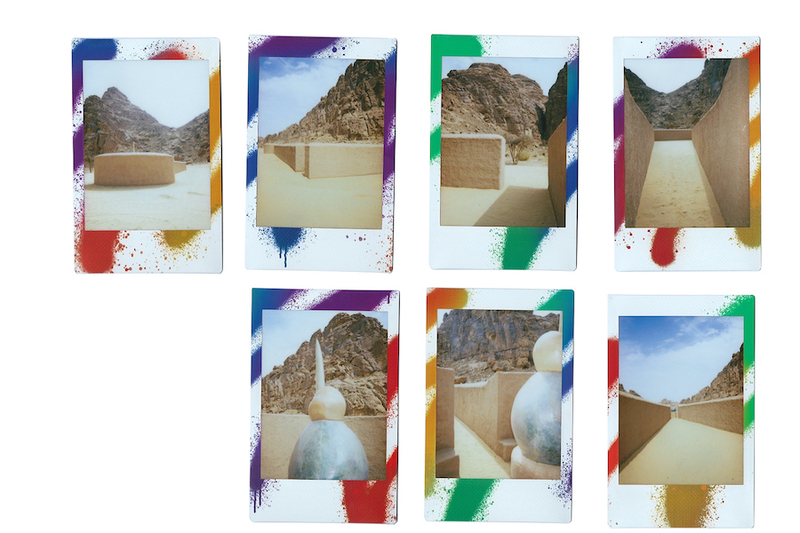

SP2 | TUMO CENTER FOR CREATIVE TECHNOLOGIES, KOGHB

The first building that came to my mind is the iconic Sevan Writers’ Resort, one of the best-known examples of Soviet Modernism. However, after learning about suggestions by other founders of Library for Architecture, it appeared that almost all preferences were Armenian, meaning Soviet, Modernist buildings in Armenia. So, I decided to write about another building, yet to be inaugurated next Spring. It is the Tumo Center for Creative Technologies located in Koghb, which was designed by the Beirut-based architect Bernard Khoury. The bunker-looking, exposed concrete structure of this building is a good example of how an educational institution, while bringing an appropriate building for a good learning environment to a small and decaying rural settlement, also transforms the common space into a new type of common place and a different, more urban life.

Sarhat Petrosyan

Tumo Center for Creative Technologies located, Koghb

Photos by TUMO Center

Daap

This music house was built by architect Stepan Kyurkchyan in 1977. It is not just a building, but also an urban sculpture with crossing insides and outsides. The stepped development of the volumetric composition and local material used, harmonize the house of chamber music with its park surroundings. Like a pop-up book, it creates saturated space by the consequence of freestanding walls and support-less roofs.

Aleksandr Danielyan

Komitas Chamber Music House, march 2024

Photos by Mitya Lyalin

d`Arvestanots | A HOUSE IN THE MIDDLE OF NOWHERE, CHURCH OF ST. VIRGIN MARY OF KARMRAVOR, ASHTARAK

The first (and most honest) thing that came to mind was to share my favorite building from my student years—the 7th century Church of St. Virgin Mary of Karmravor (Red) in Ashtarak, which amazingly combines external modesty with grandeur and a strong emotional impact in the interior. Also I want to show a photograph of a house somewhere in the village. This house, adapted by the owner to the needs of the family, could have graced the portfolio of a fashionable architecture studio.

Arsen “Shur” Karapetyan

House in an unknown place. Year unknown

Photo by Arsen “Shur” Karapetyan

Church of St. Virgin Mary of Karmravor, 2015

Photo by Yerevantsi / Wikimedia Commons

Church of St. Virgin Mary of Karmravor, 2015

Photo by Yerevantsi / Wikimedia Commons

Church of St. Virgin Mary of Karmravor, 2015

Photo by Yerevantsi / Wikimedia Commons