Harun Farocki's meditative documentary on brick making in Africa, India and Europe was screened on (EE) Films from November 13th to 21st. The screening was accompanied by an insightful text by Utte Holl about how by letting the images speak for themselves, this film shows us how bricks shape spaces and organize social relations in different parts of the world.

Bricks are the resonating bases of society. Bricks are layers of clay, simply very heavy records. Like records they appear in series, but every brick is slightly different—not just another brick in the wall. Bricks create spaces, organize social relations, and store knowledge on social structures. They resonate in a way that tells us if they are good enough or not. Bricks form the fundamental sound of our societies, but we haven’t learned to listen to them. Through different traditions of brick production, Farocki’s film has our eyes and ears consider them in comparison—and not in competition, not as a clash of cultures. Farocki shows us various brick production sites in their colors, movements, and sounds. Brick burning, brick carrying, brick laying, bricks on bricks, no off-commentary. 20 intertitles in 60 minutes tell us something about the temporality of working processes. The film shows us that certain production modes require their own duration and that cultures differentiate around the time of the brick.

In some countries and societies, brick production is very close to the human body: mixing the clay, pressing it into molds, piling them up for drying and firing. The way bricks are carried—mostly by women—in Burkina Faso and in rural areas in India, leaves a physical trace that is probably as old as the firing of bricks. Collective movement: two women bear the burden on each other’s heads. They walk cautiously through the production site. Bricks are stable and porous at the same time. They require careful manufacture, transportation, and storage. At first glance, this looks like grace. Then the camera shows us in more detail: these forms of organizations have more to do with ecology than economy. One hand has to look after a child, one has to take care of fellow workers, one has to scratch a back. Production and history develop not in lines but in hyperbolae.

When walls are constructed by hand with the aid of set squares and pendula, brick-laying appears as a mode of thinking. Low voices everywhere, words of coordination—in Burkina Faso more rhythmic, louder. In addition, the gaze comes into play in India. In construction sites in Africa and India, the soundman also records birds, dogs, buckets, and footsteps apart from the sounds of clay and brick. Then, with the progress of mechanization, the sounds of children, dogs, and women disappear from the scene. India is a kind of museum of brick production. Devices from colonial times that require troops of bearers. Machines from 1930, “the same routine since then,” says the intertitle; and since then the same hegemonies, tied within the bodies. That’s what the images show us.

Bricks form the fundamental sound of our societies, but we haven’t learned to listen to them

In Europe, the history of brick production stubbornly follows the course of industrialisation. Machines intone the rhythm; workers become their functionaries. Here bricks finally do become just another brick in the wall: prefabricated walls are being installed. A foreman orchestrates the construction with his thumb, a mere servant to the process. The film lays out corridors of time: production facilities from 1945 in France, operated by Moroccan workers, only male workers to be seen, no more voices, no more glances. Lonely work: travailing, slaving—different from the construction sites in India and Africa, which seem no less strenuous. In today’s Europe, bricks are produced by intricate machines, workers sitting in front of them, playing the clay like Orff instrumentsOrff instrumentsSimple musical instruments played with mallets that are a part of the music education practice known as the Orff Approach. It was developed by the German composer Carl Orff during the 1920s., boing/boing, either/or, material or waste.

Difficult to sit in Hamburg, writing a text on Farocki’s film and not to think of brick production as extinction by work: brick factory NeuengammeNeuengammeA quarter of the district Bergedorf within Hamburg, Germany. Before and during World War II, a Nazi concentration camp was established there by the SS. (Editor’s note). for the Führer’s New Hamburg. But Farocki’s images follow another lead. Not only do they depict the industrialization of work, but they also indicate the possible knowledge hidden in these forms of production and cultural techniques. Children play around on school construction sites in Africa. In India, they stand around, get in the way, watch their parents at work, even in unfinished buildings on the seventh floor. They are not removed when they hold on to wheelbarrows and they don’t only start learning about construction once they are in the classroom. And on the construction sites, they not only learn about construction but also about thinking in material and movement within social relationships.

Cameraman Ingo Kratisch’s movements follow those of the bricklayers. In front of machines he has to remain static in order to observe what’s going on. Elsewhere it becomes apparent that what we simply call a brick is something more differentiated in other parts of the world: optically, acoustically, and socially. In countries like Burkina Faso and India, new modes of brick production and construction are being developed that are not industrial but ecological—in a very complex sense. Here, unique economies, social relations, and types of buildings are being produced. Their starting point lies where modernism in Europe has squandered itself: at the arch.

In countries like Burkina Faso and India new modes of brick production and construction are being developed which are not industrial but ecological—in a very complex sense

And here they are—the students of architecture, trying —still without grace—to understand the new building technique, but Farocki shows us how they eat from the tree of knowledge for a second time when they chew on their pencils while drawing. The film has to show what it is able to think while filming a brick arch.

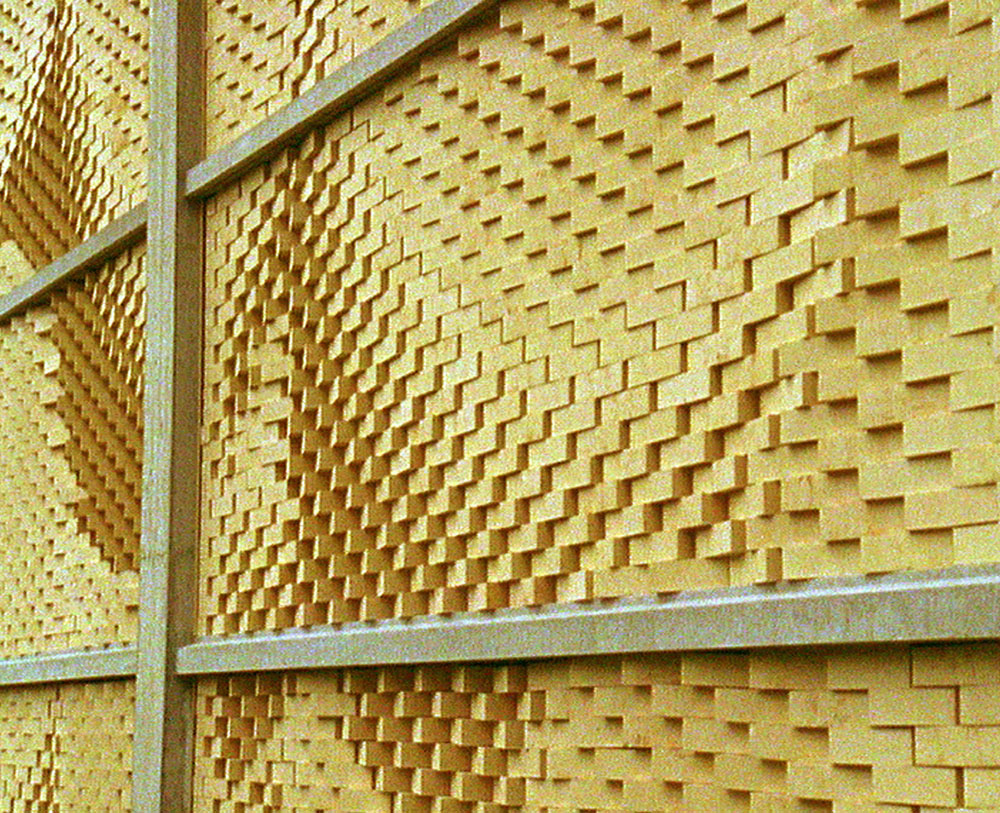

The short history of the brick is not a linear one but plays itself out as a discovery of resistance within the history of building. Heinrich von Kleist described the arch as an antigravity construction of collapsing relations. Arches are ecological in the most complex sense. At the end of the film, an astonishing short circuit: a marionette-like Swiss robot builds walls that are images. No human being in sight, nothing recognizable to the human eye during the process, only the camera eye and an image for robotic, puppet consciousness. In Comparison is Farocki’s marionette theater, a filmic preparation for the “last chapter of the history of the world” as Kleist would have it, or at least, cinematic history

Translated from the German by Antje Ehmann and Michael Turnbull

In: Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom? Edited by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun. Koenig Books, Raven Row, London 2009, p. 155-160.