Photo by Julián Velásquez © Qatar Museums

In the "Colors of the City" exhibition at Design Doha 2024, architecture historian and curator Péter Tamás Nagy explores the dynamic architectural landscape of 20th-century Qatar. Nagy has examined the historical and cultural narratives behind the unique Doha Deco style and the development of Doha Brutalism, revealing the influences that shaped these distinct trends. His research uncovers surprising stories of notable structures that define Doha's architectural heritage.

Towards the Show

During my time at university, I first studied Arabic while repeatedly traveling and living across the Middle East and North Africa. I have always been captivated by history and particularly impressed by the built environment. Consequently, what started as an interest in reading Arabic sources about old monuments—be they forts, palaces, mosques, or archaeological sites—exhilarated me into a more systematic exploration of material culture, which I find the most enthralling remnants of the past. My path then gradually shifted to art history and archaeology, and my different interests eventually came together in specializing in Islamic architecture. After finishing my doctorate in this field, I received an offer from Qatar Museums to study the local heritage, which remains my role to this day.

In Qatar, I began my research with the Palace of Sheikh Fahad bin Ali, which soon turned out to be one of the finest examples of what I define as Doha Deco, the local variant of Art Deco architecture specific to the city. Once I understood the building's history, I looked for analogies in palaces with similar decorative and structural features. Of course, each separate site required a case study to define its patron, artisans, and dating, especially since most basic information was unavailable (or unreliable) in the few previous publications. Hence, my training in art history came in handy, and the ensuing research resulted in piecing together a hitherto uncharted story about the Doha Deco phenomenon.

© Middle East Centre Archive, Oxford

The inception of this exhibition, Colors of the City, came about after Glenn Adamson had mapped out all the other shows that were to open at M7 as part of the Design Doha Biennial. What he was missing was the local element that would tie all these exhibitions to Doha, so he convinced me to think of an exhibition about the city's architectural landscape. I first designed the general narrative, but since I'm not a professional curator, bringing this narrative into a physical display was a brand-new challenge to me, not to mention that the background research had yet to be completed. The exhibition aspired to showcase some newly “discovered” and documented buildings, something that people hadn’t seen before, alongside many well-known pieces.

Mysterious Fishes

In the 1950s and '60s, various members of the royal family, the Al Thani, established new palaces near each other, which are among the most impressive monuments from the period. To single out one, I would mention the palace of Sheikh Ghanim bin Ali. Although much of the compound is off limits as it is still inhabited today, one can freely admire its east portal, which initially served as the public entrance. It was made entirely of terrazzo, adorned with a rich array of decorative details, blending typical Art Deco elements with local motifs. Additionally, the top of the portal once boasted two fish statues, which must have wowed many by-passers as long as they were in situ.

Photo by Charles Butt, 1967 © Middle East Centre Archive, Oxford

Right: East Portal, palace of Sheikh Ghanim bin Ali, completed c. 1965

Photo by Péter T. Nagy, © Qatar Museums

When I first found out about the statues, they struck me as most peculiar, and I started digging into the story behind such a flashy feature, searching for analogies. I soon found myself strolling through the streets of Lucknow, a lovely city in central India, where you could barely see a single monumental gate without a pair of fish sculptures, as they were once a royal symbol for the local principality. The hundreds of examples are obviously similar—indeed, physiognomically akin—to those in Doha. Thus, the story of fish statues is among the key pieces of evidence for the origin of the artisans or architects who created those Doha Deco palaces, indicating that they came from South Asia, India and Pakistan.

Photos by Péter T. Nagy © Qatar Museums

Ghanim Bin Ali added this portal to his older palace around 1965. By then, Art Deco was no longer fashionable but rather extinct in most parts of the world, except in South Asia, where it remained popular well into the '60s. And yet, no one has attempted to look for analogies between Doha and India . . . where else could it have come from?

A Missing Gate

Another project has required me to research the Zaman House. It was a typical family home from the 1950s, built around a rectangular courtyard. Since Qatar Museums has acquired the property, we plan to turn it into a museum, part of which will present my findings on its history. We are honored to collaborate with the Zaman family and have conducted recorded interviews with those who grew up in the house. They can confirm many details about its history and how the family applied modifications and expansions while also informing us about their social life. One of them recalls that Iranian craftsmen were involved in decorating the house, working specifically on the main gate when the family heard about the assassination of John Kennedy. This is how we know the gate was under construction in November 1963.

Photo by Julián Velásquez © Qatar Museums

Right: Zaman House, original decoration of the main gate, completed c. 1964.

Although the house exists today without its original main gate, I came across a few old pictures showing it with a peculiar, nearly Classicist decoration around an arch. Surprised and intrigued, I immediately commenced my search for analogies. Since a few similar pieces of this stylistic trend soon turned up in and around Doha, they allowed me to sketch up a larger picture and eventually comprise another part of the exhibition titled Doha Classicism.

In some cases, the exhibited buildings no longer exist, perhaps because only a few people recognise them as heritage architecture that needs to be preserved. If not without difficulties, I do what I can to explain to colleagues and the wider public why these buildings matter, and the exhibition is my most substantial attempt so far. Today, these buildings are gradually on the brink of disappearing due to negligence or a change of taste. In the case of Bayt al-Zaman, we know that when the family moved out in the mid-‘80s, the new tenants turned it into a restaurant, and this was when the gate was no longer fitting for them, so they changed it without recognizing its artistic value.

© Aga Khan Trust for Culture

The third major part of the exhibition focused on Doha Brutalism, looking at a slightly later period, the '70s and '80s when international modernist styles emerged in the city. Not all buildings featured in the exhibition were brutalist, but some had a close resemblance to the general concept behind that trend, displaying rough materials and striking forms rather than decorative details. In these cases, the buildings also sought to incorporate local, vernacular, or Islamic elements. Many proposals by international “starchitects” were turned down because the submitted designs could have stood anywhere else, while the Qatari authorities were looking for something meaningful to the specific location.

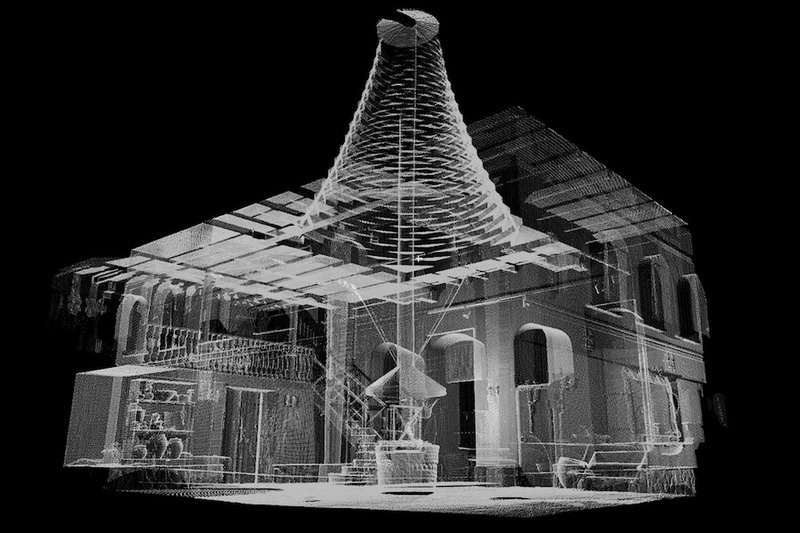

One of my favorite examples from the Doha Brutalism section is Qatar University. I find it an ingenious combination of a traditional form with a showily modernist appearance. Designed by Egyptian architect Kamal El Kafrawi and completed in 1985, the campus occupies a large area with numerous low-rise buildings, mostly octagonal modules, each topped by a badgir (or wind tower). Such wind towers were typical in historical Islamic architecture, especially in Iran. Here, El Kafrawi transformed it into a modern, not only decorative but also functional, element that picturesquely dominates the landscape all around the campus.