Reconstruction works on the building, 2018

All photos provided by the author

Author Alex Fisher provides new context for an artwork with meanings that reflect the history of a neighborhood, the settler-colonial orientations of Soviet policies in Kazakhstan, and new forms of "cultural archaeology." By peering through the sgraffito, Fisher considers the past, present, and future of Tselinny Cinema in Almaty.

In Almaty’s Golden Quarter, a “temple of light” is being revitalized. The quarter is the central district in Kazakhstan’s cultural capital. Laid out on a grid, the quarter brims with pedestrian greenways and stately residential blocks. It is also home to social infrastructure, including what Dennis Keen, a scholar of Kazakhstan, refers to as the temple of light—Tselinny, a cinema that opened in 1965 and is currently being renovated into a center of contemporary culture. This article anticipates the ideologically-charged venue’s reopening, scheduled for early 2025, through an analysis of the composition, condition, and contextual implications of the monumental artwork located therein—a sgraffito by Yevgeniy Sidorkin.

Sidorkin (1930-1982) was a Russian-born graphic artist and illustrator who made his career in Kazakhstan. He created his sgraffito for the main wall in the Tselinny atrium. The work’s four scenes hearken to socialist rhapsody; from left to right, Sidorkin depicts: a racially ambiguous family recreating under Almaty’s illustrious apple trees; two horses jumping, ridden by men in traditional garments; women dancing to a dombyra dombyra A long-necked musical string instrument used by the Kazakhs, Hazaras, Afghans, Nogais, Bashkirs, and Tatars in their traditional folk musicplayer; and a couple lounging outdoors. Kazakh ornaments lace through the work, loosely tying the scenes together.

Sidorkin renders his subjects in sharp lines—the father’s pecs are chiseled, the dancers’ dresses hug their hips, etc. Everything in the sgraffito is form fitting. Moreover, the sgraffito’s form befits Tselinny, indicating how this piece of social infrastructure was inserted on its site. The scenes are incisive, cutting to the point of pleasure. Tselinny, too, was wrought with precision. In the venue’s immediate vicinity are an orthodox church, park, and bazaar, all of which were established when Almaty was under Russian imperial rule. If this assemblage might previously have sustained residents, it did not suffice for the Soviet century. Tselinny arrived as a marquee for socialist-style modernization.

Tselinny’s architecture enhanced Sidorkin’s sgraffito, and vice versa. Because the façade was a glass screen, the atrium seemed like an extension of the sidewalk after sundown; the boundary between the world of exteriors and interiors was transparent, imparting that entertainment was for everyone. At night, Tselinny radiated; the cinema’s light spilled through the screen, and the sgraffito came alive. Pedestrians strolled by in tandem with the jumping horses while filmgoers communed with the family and couple in the garden of delights. Zhanna Spooner, an architect who grew up nearby, recalls that the effect was magical.

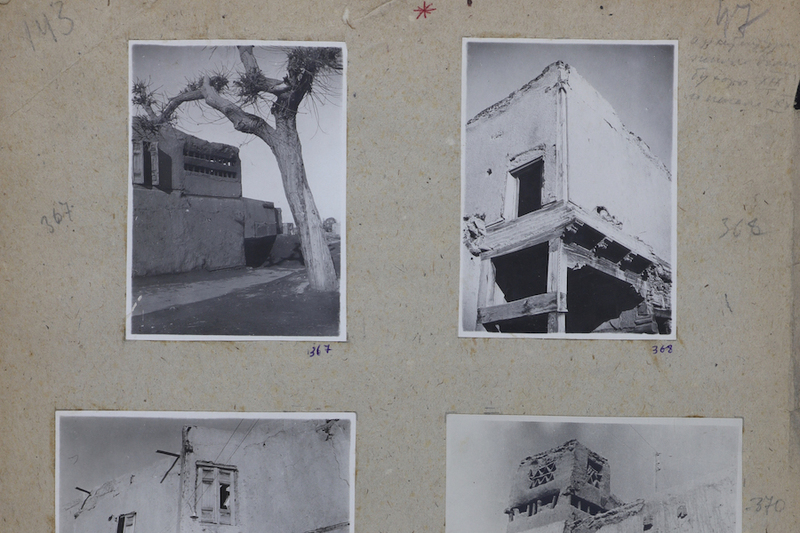

Above right: Tselinny Centre of Contemporary Culture, 1960s. From the album "Alma-Ata," Complied by M. Baisurov in 1978

The Central State Archive of Film, Photo Documents, and Sound Recording of the Republic of Kazakhstan

Below: Tselinny movie theater facade, 2018

All photos provided by the author

Radiant Tselinny is ingrained in the collective memory of Almaty residents of a certain age, the physical embodiment of an era of promise. The cinema opened during Khrushchev’s thaw, when restrictions on civil liberties were (inconsistently) slackened across the Soviet Union. In Kazakhstan, the thaw is synonymous with the ascent of Dinmukhamed Kunaev, a charismatic party chairman who burnished Kazakhstan’s credentials in the union and oversaw a range of infrastructure projects that aimed to improve quality of life in the then-republic.

Tselinny’s association with that lapsed era of promise informed its eventual repurposing after the Soviet Union dissolved. The cinema creeped along in the 1990s before it was privatized at the dawn of the new millennium. The first private owners turned Tselinny into a multi-function space, adding a nightclub and other commercial ventures. In the process, the venue’s structural integrity was disturbed. Despite the objections of Sidorkin’s children and cultural activists, the glass screen was replaced and the sgraffito was covered. In a concession, Sidorkin’s son and his son’s wife were commissioned to make a replica of the sgraffito on the exterior of Tselinny. In a curious twist, many residents came to believe that the replica was the original.

The first owners struggled to turn a profit; in 2016, they ran out of options and surrendered the property, which was subsequently re-sold to Kairat Boranbayev, a prominent businessman who had earlier converted two Soviet-era cinemas in Almaty into restaurants. A diverse coalition of stakeholders lobbied Boranbayev to restore the venue’s integrity rather than disturb it further. In a sign that corporate social responsibility was taking root in Kazakhstan, Boranbayev heeded the coalition’s call, electing to transform Tselinny into a center of contemporary culture.

All photos provided by the author

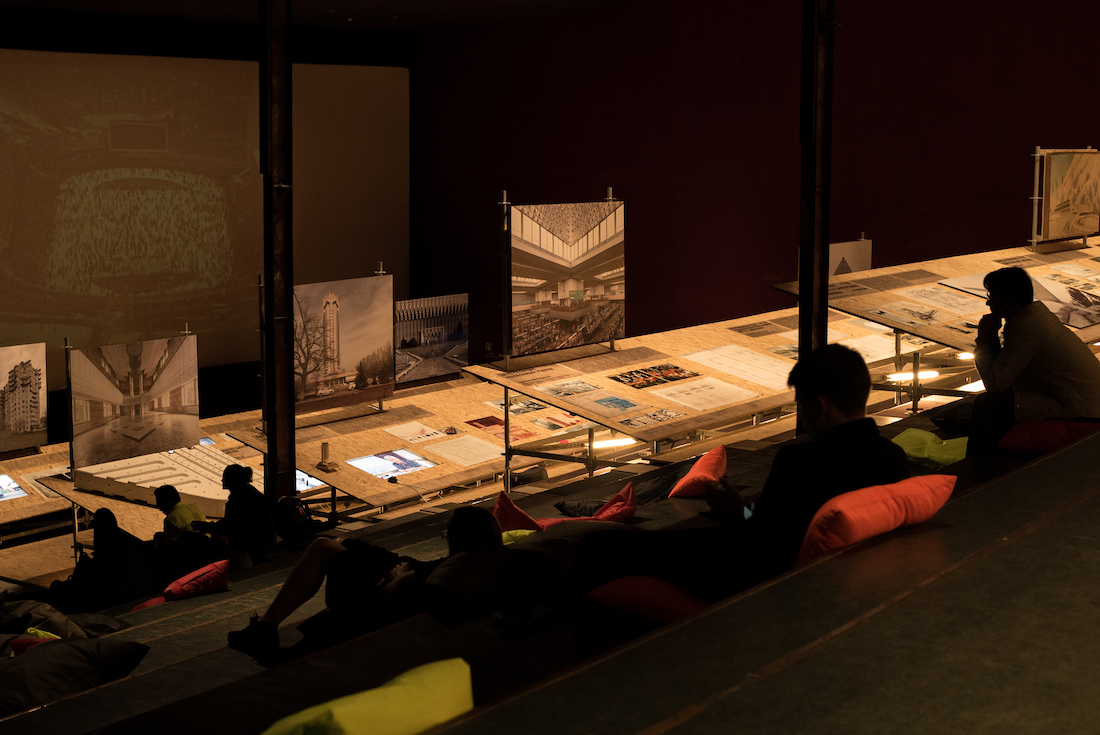

In 2017, the British architect Asif Khan was appointed to lead the renovation of Tselinny. His appointment followed his participation in Expo Astana, where he had won acclaim for his UK Pavilion. The architect’s first visit to Tselinny left him with the impression of a venue drained of its life force. Confronting radiant Tselinny’s diminishment into an ember, the renovation has taken a concerted approach that Khan likens to “cultural archaeology.” Tselinny’s layers have been peeled back, revealing details that have thrilled (e.g., the discovery of the original sgraffito beneath drywall) and frustrated (e.g., the finding that the foundation had to be redone).

Notably, Tselinny’s cultural archaeology has extended beyond the construction site. As drywall was being removed, Tselinny initiated a range of interdisciplinary projects that have functioned as intellectual scaffolding throughout the protracted renovation. This includes a guide to Soviet modernist architecture in Almaty, published by the Garage Museum with Tselinny’s support. Released in 2020, the book has helped renew local interest in the architectural style, heralding a modest modernist revival.

Several publications that Tselinny has released under its own imprimatur have explored how cultural productions have helped construct, or deconstruct, problematic “civilizing missions” in Kazakhstan. One conviction that the center’s team has developed over the course of publishing these titles is that, not only is it logistically impossible to fully restore Tselinny, doing so would be unjustifiable. Here, it should be noted that Tselinny’s name derives from Tselina, otherwise known as the Virgin Lands Campaign. Executed in the 1950s on Kremlin orders, this campaign turned the territory of Northern Kazakhstan into arable land for cultivating grain. Carried out to alleviate food shortages across the Soviet Union, the campaign had serious environmental consequences. It also altered the demographics of Northern Kazakhstan, since a large share of people who worked on the campaign and remained in the area were ethnic Slavs.

Reconstruction works of the building, 2024

All photos provided by the author

At the time, Tselina was officially regarded as a triumph, as evidenced by its commemoration in cinema-form in the Golden Quarter. (The cinema’s neon sign included a stalk of wheat.) As time goes by, the campaign increasingly looks like a case of settler colonialism oriented around extraction. It follows that the renovation of Tselinny has stirred critical discussion on what decolonizing Kazakhstan means in theory and practice. Appreciating the importance of this and related discussions, the center strives to become a space where opinions and objectives are exchanged. To this end, in the new Tselinny, the former atrium and cinema hall will be known as “forums”—marketplaces for ideas of all sorts.

Tselina is but one of many specters that inhabit Tselinny. The presence of these specters is the source of Tselinny’s strength and weakness. Khan’s recognition of this dialectic has structured his renovation approach, including his engagement with Sidorkin’s sgraffito.

As noted, during the renovation, it was determined that Tselinny’s foundation had to be redone in order to comply with contemporary building regulations. Laying a new foundation meant disassembling Tselinny, including the concrete wall with the sgraffito. And the only way to disassemble the wall without destroying the monumental artwork was to cut the wall into pieces. As a result, when Tselinny re-opens, visitors will encounter a fragmented version of the sgraffito, whose complexion will clarify that the work has always been a montage.

In conversation, Khan speaks of his desire not to replace historical material. This desire extends to his treatment of the replica of the sgraffito created for Tselinny’s exterior in the 2000s. The architect came to understand that, not only had many residents come to believe that the replica was the original, they depended on the replica as a wayfaring device. The replica marked where pedestrians should turn to access the church, park, and bazaar, enabling them to navigate the Golden Quarter while referencing images rather than words. The renovation of Tselinny honors this legacy by turning Sidorkin’s sgraffito into a visual language. The center is being covered in cladding inscribed with shapes based on the sgraffito’s constituent parts (e.g., a horse’s hoof). Further, in Tselinny’s forthcoming education wing, one of the windows has a distinctive cloud-like shape, which is molded on an element in the monumental artwork. Patrons will see through the sgraffito; more precisely, they will see through an abstraction of the work placed where its replica previously appeared.

Soviet monumental art was an art for mass enlightenment. While not without its merits, it was highly codified and left limited room for the imagination—Sidorkin’s sgraffito included. With this in mind, it is worth dwelling on what the window molded on an element in the monumental artwork portends for the center. During the day at the renovated Tselinny, a portal derived from the art for enlightenment will let light in. After sundown, it will let light out. The multiplicity and multi-directionality inherent to that process can be expected to have an ordering effect on Tselinny, whose sights and narratives will be seen in many lights.

The author thanks Dennis Keen, Asif Khan, Almas Ordabayev, and Zhanna Spooner for sharing their insights.

To learn more about the Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, visit http://tselinny.org.