Photo by Marco Cappelletti with Filippo Rossi and Eugenio Schirone

Through a constellation of initiatives and teams, the combined forces of Space Caviar and the Practice Lab at re:arc institute are working to establish a new paradigm: non-extractive architecture(s), a detailed ongoing directory that aims to address challenges both internal and external to the field. In conversation with EastEast, representatives Sofia Pia Belenky (Space Caviar) and Nicolay Boyadjiev (re:arc Practice Lab) discuss the terminologies, geographies, and philosophies that inform and define the program.

Full text of the book can be found here

We’ve always been fascinated by the inverse idea, particularly in the form in which it emerged during the period you reference: the architect as a full-spectrum designer who actually does know at least the basic principles of how to repair a roof, or pick good lumber, but is also capable of strategic thinking around multi-century material procurement strategies integrated into the urban landscape, or non-depletionary stewardship policies for production and reuse of buildings, and at the same time is driven by curiosity and the impetus to research and continually widen their horizon of knowledge. The essence of the writing of Ivan Illich and Buckminster Fuller in this period largely comes down to a fierce diatribe against specialization—they were almost maniacally convinced of the need to be-specialized to survive, and this idea influenced the philosophy of the Non-Extractive Architecture project considerably. Non-Extractive Architecture is in many ways an invitation to zoom out and zoom in at the same time, and in any case to get away from screens a little more. This is something we attempt to practice ourselves at Space Caviar, where we always hang on to a certain hands-on engagement in all of our projects.

I think the long-term goals of the project are to propose an alternative model of what it means to be an architect, especially to young people getting into the profession now. Architecture and design schools tend to be locked into a certain understanding of the architect's role in society and the heroic, modernist model they hold up as an example for young designers tends to be self-perpetuating, with consequences that are not always desirable (for society in general, but also for architects themselves). Rather than addressing design challenges from a purely programmatic or compositional perspective, as schools tend to train students to, we want to start from the very end of the story: how can I solve this design problem in a way that will not simply shift the problem, perhaps in a different form, somewhere else?

It sounds simple, but in fact, it's incredibly difficult because much of the prosperity we have collectively achieved is simply a function of externalities we've created elsewhere, usually in poorer countries further south. Unpicking the supply chains our daily lives depend on and rethinking these productive activities so they weigh on our own shoulders and not the shoulders of others is going to take a very long time—we literally have to unlearn what we've been taught and in some cases start over.

Photo by Marco Cappelletti with Filippo Rossi and Eugenio Schirone

For me this has implications both for architecture “industry” and “practice,” because the built environment is hiding in plain sight both amongst the worst contributors to the climate crisis but also amongst the most powerful sites of leverage in the context of our response to it. Architecture practice (noun) would benefit from being demystified and in many ways de-linked from its vestigial attachment to the siloed “authorship” of any individual practitioner or building, and should be seen as exactly what it is: an ongoing practice (verb) to address social needs within the site-specificity of their ecological context through the mobilization of local know-how, work, and labor.

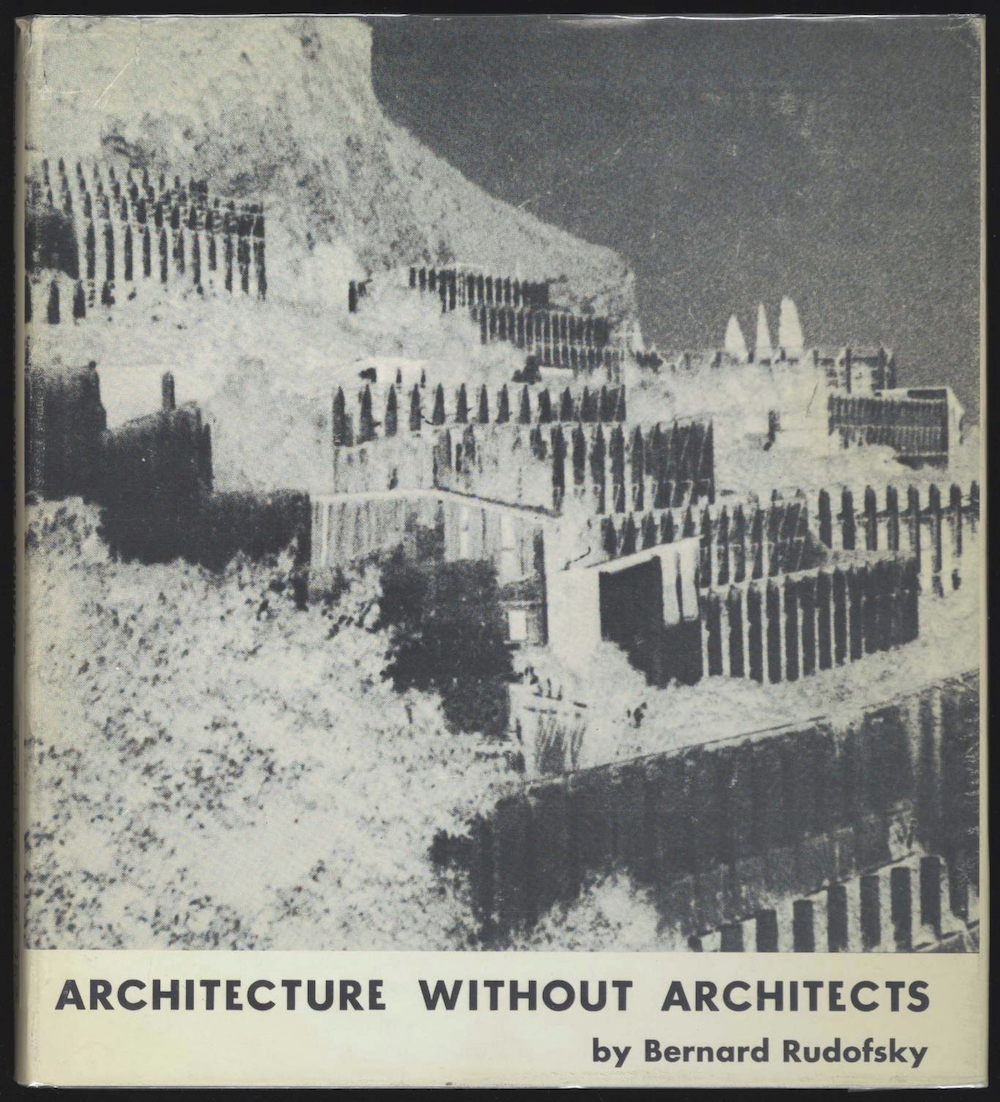

Architecture is therefore not “embodied” in individual design-objects but should rather be defined as “practiced” via the ongoing design and tending to site-specific relationships across our social infrastructures we need and the ecological infrastructures that contain us. Its evolution should be informed by its ability to give shape to the site-specificity of that relationship in the viable and pluralistic terms that are required and, to go one step further, by the necessity of re-imagining the institutions that make more ecologically responsible and socially just relationships possible in the first place. Part of our work at the Practice Lab is to address both aspects of that evolution, or to reference your Rudofsky example: to think about “architecture without clients” in the traditional sense of the term.

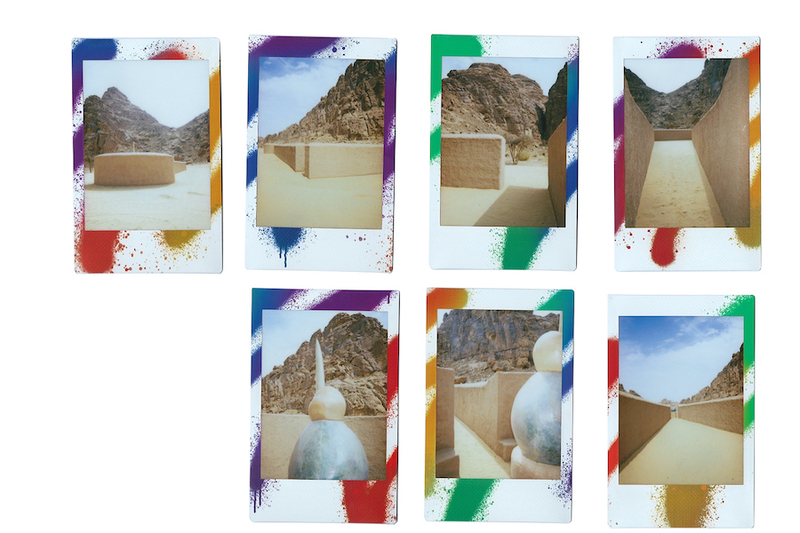

Datecrete, United Arab Emirates

Datecrete is a bio-based material developed that combines the durability and strength of concrete with the eco-friendly benefits of date palm fibers.

Arquitectura Mixta, Mexico

The studio is committed to sustainability and incorporates environmentally friendly materials and design practices into all of its projects.

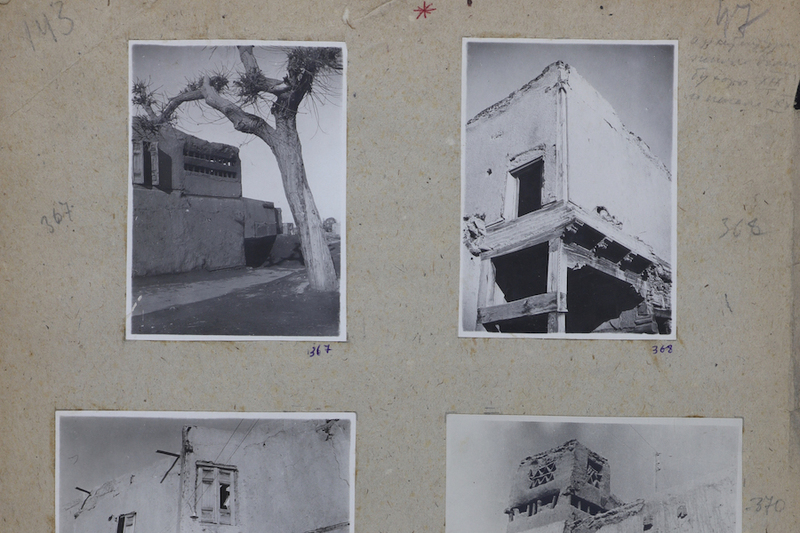

Rammed Earth Construction, Global

Rammed earth has been utilized in construction for millennia, with evidence of its use dating back to the Neolithic Period. This technique was commonly used in China for both ancient monuments and vernacular architecture, including the Great Wall.

Phumdis, Asia

Phumdis are a series of floating islands found in the Loktak Lake in India. They are composed of vegetation, soil, and organic matter in various stages of decay, and are used by local communities for fishing and other livelihood purposes.

Language is important, it’s also about reclaiming these words and giving them precise meaning that is not attached to capitalistic gains.

Awi'nakola: Tree of Life, North America, Canada

Foundation was established by a group of Indigenous knowledge keepers scientists and artists brought together by a mutual commitment to create tangible solutions for the current climate crisis and educate others through the process. Awi’nakola is a Kwak’wala word meaning “environment, including everything from the land to the ocean, and all the air in between.” The Awi’nakola Project is a research group working to keep the rich ecosystems of the some 2.7% of high productivity old growth left in the province intact.

Forest Wool, Netherlands

Forest Wool's mission is to diversify monoculture-driven fiber industries, promoting efficient utilization of underutilized resources and reducing dependence on imported, farmed fibers.

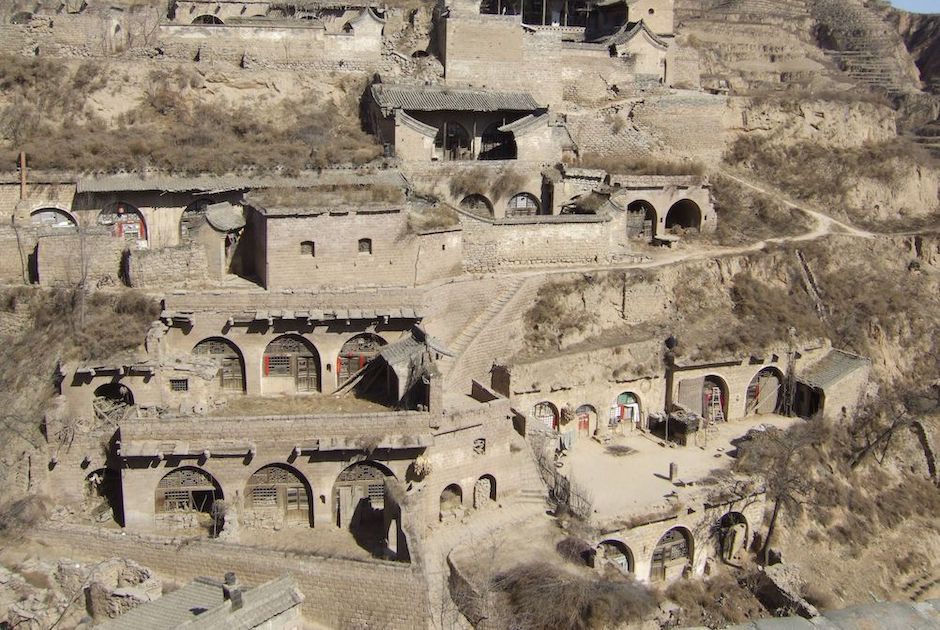

Chinese Loess Belt Dwellings, China

Yaodong is a traditional form of earth shelter dwelling common in China's Loess Plateau. They are carved out of hillside or excavated horizontally from a central sunken courtyard.

Simple Architecture, Bangkok

Simple Architecture employs a highly collaborative design process, attuned to local contexts and client needs. Their work showcases the flexibility and sustainability of indigenous materials, often featuring bamboo and adobe mud bricks.

At the Practice Lab, we have tried to address this in structural terms through the design and application of alternative “ways of working” for architects and professional practitioners by commissioning them directly to realize local, self-initiated, and community-led projects that address highly site-specific social/ecological challenges. While at an individual level, practices are working on local interventions quite different from one another, at a broader institutional level we at the lab are learning from their process and working on building corresponding legal templates, protocols, and blueprints that can standardize, accelerate, and scale this kind of work. Our goal is to help establish precedents for the non-profit sector to work directly with architectural studios—”non-non-profits”—in ways that leverage impact way beyond what an individual project, firm, or even philanthropic foundation can do on its own.

Our hope is that the design of these blueprints can shift larger trends both within the architectural industry (normalizing and scaling this typology of site-specific socio-ecological infrastructural projects not by individual growth but through collective multiplication) and the philanthropic industry (normalizing new tried and tested ways of working directly with architectural practitioners in order to help society realize projects that aren't incentivised across current market-driven or culturally-rewarded channels). In other words, I think of the planetary movement we are hoping to achieve less through the format of a manifesto about the “what” or “why” than through the format of a proven alternative operating model for the “how.” Philanthropy or as we refer to it “Para-Philanthropy”—not “anti,” “better”, “fixing” philanthropy but “in parallel to” philanthropy—is a space of possibility and a genuinely interesting space of design to explore this.

Pooling Xolox will be a water basin that acts as a community space and a collection area for water run-off created from the construction of a cancelled Mexico City airport. It is planned for the town of San Lucas Xolox, where water runoff from construction-created divets in the land have led to the flooding of infrastructure for the locals. Instead of rerouting the water beyond the town's limit, Taller Capital hopes to divert and collect the water into a basin created by the earth, which also acts as community space where excess water might be used for agricultural purposes.

Project was supported by The Practice Lab by Re:Arc Institute in 2023 and now in construction

The transition towards a non-extractive approach to design is a function of a larger shift in the scope of economies and should be recognized as an opportunity for increased, not diminished, collective prosperity. The goal is to create a global movement; we feel hopeful in the incredible breadth of practices and ways of practice we have discovered while working on this platform and believe that there are no alternatives to working in this way. It will require a global movement and a collective effort from all disciplines.

The reasons why we work predominantly in the so-called “Global South” are very pragmatic: the reality is that the effects of the climate crisis are not evenly distributed and this is therefore where some of the challenges are the most pronounced / where design interventions are most needed, as well where their reverberating effects are most impactful. Sadly, the most sustainable “carbon-neutral” building in Copenhagen or Amsterdam won’t matter if we don’t address deforestation or biodiversity loss in Central and South America. Additionally, the know-how and expertise of how to deal with these challenges already exists in situ: it isn’t about importing one-size-fits-all solutions or about re-skilling/up-skilling based on European or North American standards, but rather about recognising and elevating the skills and methods that already exist on site when relevant. As such, we share your point on avoiding to superficially “reward” a performative type of vernacular formalism/orientalism that fetishizes non-Western forms for the benefit of Western audiences, and strive to create and build a decentralized process within philanthropy where we work to find highly competent local practices/communities and commission them through highly open-briefs to realize projects with the knowledge they already have, but which isn’t always formally recognized or incentivized in practice.