Copyright Marco Cappalletti, courtesy of OMA

Sumayya Vally’s projects include an extremely wide range of geographic, conceptual, and historical approaches while still maintaining a shared connection to her architectural practice. From reshaping spaces at the Islamic Biennale, where narratives unfold spatially and atmospherically, to curating relationships in her Serpentine Pavilion through institutional collaborations, Vally's approaches provide models for new modes of engagement with communities and place. In an interview with EastEast Contributing Editor Lesia Prokopenko, Vally discusses visions of the future and the possibility of new architectural traditions that move the discipline into uncharted territories.

If we look at it like that, then we can understand that it is also really key for us to think about what different forms and methods can emerge from cultures that are not present in the mainstream architectural canon.

I think the other arenas of my creative practice are really investigations of this. At the Biennale I was really thinking about the rituals that construct our spiritual belonging—both individual (the moment of readying for the daily prayer, from the sound of the call to prayer, from hearing the sound, ablution, and orienting ourselves to Makkah) and communal (rituals of eating together, collective memory, imagination, collective worship, and celebration).

It has also been said that I bring a curatorial hand to my architectural works, because I am often involved in building relationships around the project. For example, the fragments of my Serpentine Pavilion were the result of the various institutional collaborations that developed alongside the project. Four fragments of the Serpentine Pavilion were placed in partner organizations whose work inspired its design. They support the everyday operations of these organizations while enabling and honoring gatherings of local communities that they have supported for years. In addition, we developed Support Structures for Support Structures, a grant and fellowship program that supports artists who work in, support, and hold communities in London through their work. These decisions, spatial, formal, and programmatic, are curatorial, yes, but for me they also represent a different method for architecture—one that is diasporic, networked, and collaborative.

Above: Valence Library

Below (left): The Albany

Below (right): The Tabernacle

Photos by George Darrell

I think the project of architecture requires so much humanness—now more than ever—so the two are inextricably linked. For me, the seeds of architecture were first planted while spending time in the city of Johannesburg, where my grandfather has stores on Ntemi Pileso Street. These encounters with spaces outside of my own played a crucial role in the way I saw the city, and harnessed in me a desire to imagine new worlds inspired by its magic.

I’ve always had an interest in finding and creating worlds, and in seeing what I truly consider architecture—the fabric of the city—as interesting starting points from which to imagine new worlds. It's very gradual, but I always had this desire to work in the city and to have a practice that brings together different parts of the city into the same world. Joburg is rough, gritty, ruthless, and fast in the nicest possible ways and the meanest possible ways. It’s a burden and opportunity at the same time. Its tensions, histories, and legacies of segregation and exclusion, mean that at every turn there’s work to do. But it’s also a vastly and vibrantly creative world of inspiration, that is, in the other disciplines, not in architecture. There’s a sense of something other—other stories, other magic, another soul—that’s waiting to be unlocked and translated into form.

This can best be seen in my Serpentine Pavilion, which referenced and paid homage to existing and erased places that have held communities over time and continue to do so today. That logic came from thinking about diasporas, and thinking about things that root themselves or uproot themselves from one place, travel to another place, and then take on the conditions of that other place. I looked at spaces that were important for migrant communities when they first moved to London, and I thought about some of the first mosques, churches, synagogues, but then also marketplaces where people would be able to find traditional ingredients for recipes, or some of the first venues to play black music in London.

Photos by Iwan Baan

While these past places of gathering inspired the form of the pavilion, I also wanted to be able to take it back to those places and root the pavilion in neighborhoods in London. So in some of those same community arts institutions we embedded pieces of the pavilion that then hosted programs over time and beyond the form. That created collaborations between the Serpentine Gallery in Kensington Gardens in London and community arts institutions across London. So, the building became a kind of communication device between places. And the message for me, for that way of working, really came from thinking about diasporic logics and thinking about how people have moved across places. I started to think, what if architecture did that as well? There are material dimensions, there are aesthetic dimensions, but there are also methods of practice and ways of working that are waiting to inform architectural practice.

Images courtesy of Counterspace

Everything I look at is through the lens of a fundamental interest in territory, identity, belonging, and trying to understand architecture beyond that which is built. Architecture is complicit in separating, othering, and excluding, but it can also be a force for the opposite. Architects make walls, but we also make doors. The architecture that moves me most is architecture that makes an offering about the human condition and about people—architecture that facilitates and has something to say about our relationships to each other, and our relationships to territory and place.

There are material dimensions, there are aesthetic dimensions, but there are also methods of practice and ways of working that are waiting to inform architectural practice

Many African and Islamic traditions are not focused on static preservation, but on evolution and change. As an architect, I’m interested in how a building can convene people: not just by its structure, but through the act of making.

African Studies Centre Leiden / Fred van der Kraaij

Take the Great Mosque of Djenné in Mali for example. It is the largest mud-brick structure in the world. It was originally built in 1907, on the site of a 13th-century mosque. Every 12 months, in April, its surface is re-mudded, to reinforce the structure in preparation for the rainy season—an event called the Crépissage. Through that process, its fabric shifts over time. In a sense, it can be seen as evolving into an entirely different building year after year. On the day of the re-mudding, teams work together to daub wet clay on the walls under the supervision of 80 senior masons. As a form of architectural practice, this goes beyond planning: it requires collaboration with the weather and an understanding of the climate, its seasons, and its a performance. The skill of mudding is transferred through generations, and its heritage is deeply tied to ritual.

The mud masons have inspired so much of my work: I’ve always been interested in embodied forms of heritage and ritual. For my performance piece at the Dhaka Art Summit held in February this year, "Oletha Imvula Uletha Ukuphila” (a Zulu proverb that means: “They who bring rain, bring life), potters washed unfired clay vessels and returned them to the earth over the course of nine days. Like the Great Mosque, these vessels are also structures that are built and unbuilt.

Photos by Shadman Sakib. Courtesy of Dhaka Art Summit 2023

I often think about how different the world looks from different perspectives. This is why representation and the manifestation of our identities are so important.

Being in a place, absorbing it, ingesting it, and then translating it is very important to my design process—how do we articulate identity through architecture? Rather than a distinction between north and south (or an attitude of essentialism towards African identity), I’m interested in the complexity and intersections between them—relationships between host and home, between past and future too—we have been deeply connected for a long time. Some connections are difficult and dark, but in all of us, we have bits of both north and south, through colony, empire, and migration.

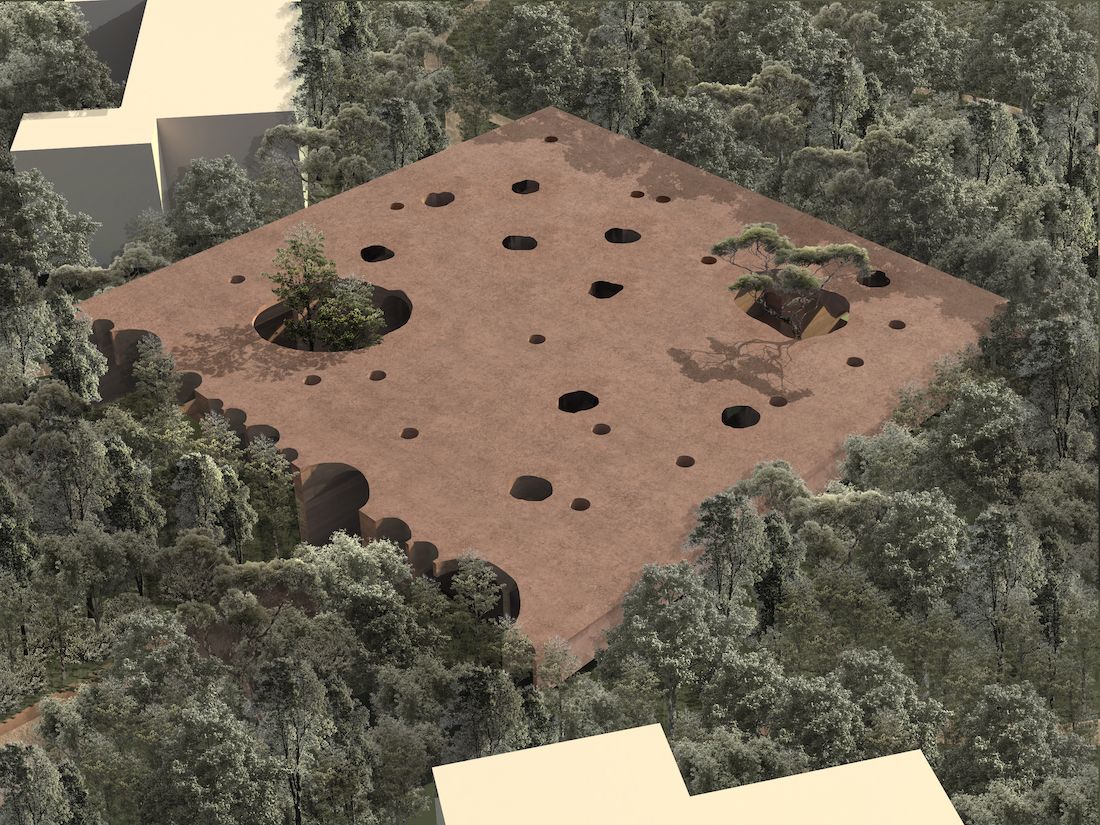

Photos by Marco Cappalletti. Image courtesy of OMA

The Islamic Arts Biennale held in Jeddah between January - May 2023, which I artistically directed, was very much an exploration of this concept of home: what it is and what it means for people of the Muslim world. Its theme, Awwal Bait (First House), refers to the reverence and symbolic unity evoked by the Ka‘ba in Makkah, and underscores the importance of the geographic location of this biennale. At the same time, it reflects on the construction of “home” through our spiritual and cultural rituals in Islam; acts which both unite us and celebrate our diversity and cultural hybridity.

I believe that hybridity is an incredible strength

As the source of Islam, The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the custodian of the two holy mosques and the sacred landscapes surrounding them—a spiritual home for Muslims from across the world—and invites the contemplation of belonging. In these rituals, we refer to our Awwal Bait, our shared spiritual home.

Photo by Ali Karimi

Right: Wave Catcher by Basmah Felemban at the Islamic Arts Biennale. Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 2023

Image courtesy of Diriyah Biennale Foundation

The theme looks at how the source has traveled, as we reflect on the migration of the first Muslims from the Awwal Bait to the city of Madinah. Many contemporary migrations in our world are synonymous with loss and displacement. In many of these scenarios, rituals become constructions of belonging–bridges between here and elsewhere, coloring a collective imagination of Muslims the world over.

However diverse, and wherever we are, Awwal Bait and Makkah (and Madinah, the city Prophet Muhammad PBUH migrated to) are present in our rituals of worship. It is present through invisible lines of direction, reverence through study and memory, or through our daily rituals and forms of cultural life. It is held in the hearts of all Muslims. This shared source manifests unity in the core philosophies of Islam, an understanding that we are connected to each other through our shared rituals, as we physically and metaphorically turn toward our shared home. Several historical and archaeological fragments inspire, narrate, and render visible wisdoms, imaginations, and futures of “home” and spiritual placemaking, from the scale of the body to the scale of the cosmos.

Photo by Laurian Ghinitoiu

I recently responded to a brief for a pedestrian bridge in Vilvoorde, Belgium. Connecting the Asiat and Darse neighborhoods there, the concept for the bridge was inspired by the Congolese activist and horticulturist Paul Panda Farnana. Though an important figure of the city and instrumental in its history, Farnana was not acknowledged for his immense impact as an activist, Pan Africanist, intellectual, advocate for black slaves, and an exceptional horticulturist. This important figure’s legacy was uncovered in my research on the city and I was left incredibly inspired by his story, which I’d never heard. The project centers him and honors his life and his legacy, while also honoring the legacies of thousands of people who are unnamed and unknown.

Images courtesy of Counterspace

For the form of the project, one of the research strands was water architectures from the Congo. During our research, we saw beautiful boat structures configured next to each other, which then became platforms for people to trade, gather, and share. The bridge takes the form of these boats and each of them are planted with species that come from Farnana’s research. Then, there are auxiliary boat structures that will embed themselves across areas of the riverbank that will pollinate industrial areas across the landscape, as well as being a metaphor for healing. Each one will become a little garden of reflection and will be named in honor of the names that we found on the slave register.

Some connections are difficult and dark, but in all of us, we have bits of both north and south, through colony, empire, and migration

We worked with plants and species from Farnana’s research to honor Farnana’s horticultural work. Each “boat” form serves as an isolated seed bed in which specific plants can be cultivated in order for their seeds to be spread on the wind and carried on the bodies of people traveling across the bridge. As a result, the bridge is a seeding bed from which plants may distribute themselves, migrating across the site.

In harking back to notions of heritage now, we also need to think about the kind of heritages we will leave behind for the future.