For EastEast's architecture issue, (EE) Films curator Olya Korsun and (EE) senior editor Konstantin Koryagin explored the foundation of the fundamentals of construction, stone, and its paradoxical nature: its ability to set things in motion while remaining the epitome of immobility. The result of this research is a meditative video essay that combines images, sounds, and voice in a mosaic that reflects the different facets of this material.

Stones connect the past, the present, and the future. They are tangible proof of events and people that were there before us and that will remain after us. Their formation is one of the mysteries of the universe, involving enormous spans of time and unpredictable changes in temperature and pressure.

Stone can be as hard as granite, as gentle as a limestone, as disruptive as liquid magma, or as light as tuff. Stones can be as large and tangible as the carved heads of Easter Island, or as abstract and elusive as myths of alchemy. They can travel from distant asteroid belts and end up as a paper weight on your desk.

Time in and around stones is condensed and frozen. Not only do stones embody eternity, but they invite us to leave eternal messages on their surface. For centuries, rock carving was practiced and developed in different cultures across the world. Stone became one of the first material canvases on which human imagination was expressed, and a public forum where the first laws were literally “set in stone.” Messages, news, laws, rules, prayers, fears, and wishes—all would remain after their authors were long gone.

Stones are our memory, recorded and externalized. We learn about the life of ancient people by examining the stones from which they made their dwellings and tools, their tombs and temples. Large boulders, standing in the middle of a desert or a steppe, could stop hunters and gatherers, rooting them to a specific place.

One might say that man moved the stone to take its place. The word Man itself comes from the Breton “maen,” meaning “stone". And the name of ‘menhirs’, allegedly the first man-made structures, literally means “long stones.” There is evidence of humans piling stones that goes back as far as 12 millenia ago, and since then stone walls, vaults, arches and domes have shaped our lived environments. Requiring nothing but stone itself – dry stone architecture pre-dated the wheel, pottery, metallurgy, and writing.

Stones are our memory, recorded and externalized

Just as a section of a stone can magically reveal the natural landscape of its origin, the identity and the way of life of tribes were influenced by the color, shape, and properties of the stone that they used to build their dwellings. These connections between the appearance of stone and the identity of those living within their structures continues to this day, affecting the architectural appearance of entire cities and regions: the dusty rose of Petra, the vivid pink of Jaipur, the soft yellow of the Mediterranean, built with Lecce stone, often referred to as the “marble of the poor.”

In each case, the stones that were found were the stones used to build, The geology of a place externalized and formulated in the shape of human architecture. These constructions were seemingly easy to raise, but required an intricate masonry craft that relied on gravity, the power of which would hold the stones together much longer than any cement or metal could. Sometimes so intimidating in their scale, works of stone architecture have been referred to as cyclopean, stemming from the assumption that only a superhuman race could have constructed them. They send us back to the times when the wonders of the world were taking place.

Because time did not have the same power over the stone as it has over us, it also became our link to the otherworldly, the eternal, the sacred world within and beyond us. The material is indeed the "foundation stone" that is, in religious tradition, the imperishable foundation of our perishable world. Ancient people built their own homes out of reeds and mud, and sacred dwellings, those meant for the gods, were made from stone. A man died and his house died with him, while a god remained immortal, as did their home. And still today, graves, memorials, and tombstones are generally made out from stone, eternal dwellings for immortal souls.

And yet, stone is not only a solid, rigid material through which we interact with eternity, but also a source of continuous change. In nature, stone represents the movement of tectonic plates, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions that change the landscapes and shapes of continents.

The moment humans picked up stones and used them as tools, a process of unfathomable change was set in motion. The rubbing of stone against stone gave us fire, one stone sharpened another, becoming tools for labor, building, and hunting. It was through manual labor, motor movements, and artisanal interaction with stone that we really became humans and developed our cognitive abilities.

Stone contains a paradox within—one that sets things in motion. It is simultaneously a tool and a form of material, an obstacle and a shelter, a relic and a weapon, a screen and a cover, a mountain and a sand grain.

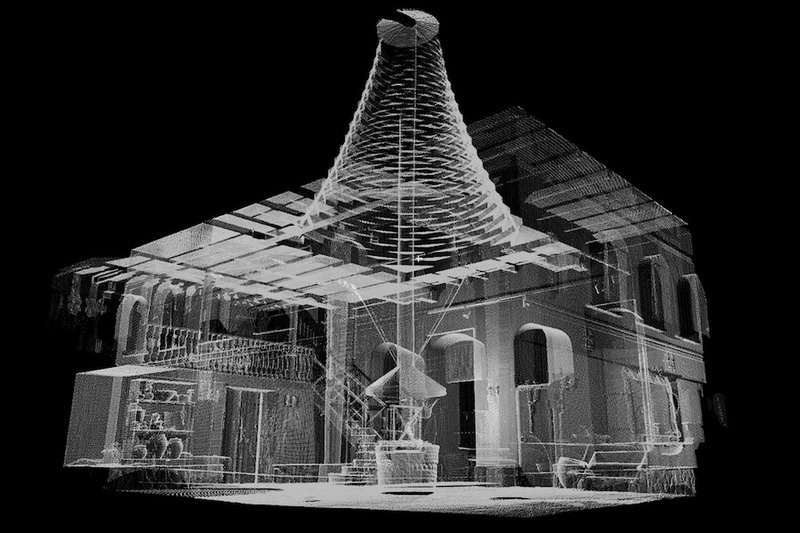

While a building stone may have 8 faces, only one of them is visible to a passerby—the facade. Only the mason knows them all. Thus, building with stone is the act of choice, of a dialogue with the material, an act of concealing the secrets of stone and revealing its radiance.

Humans build with stone, but those same stones are also used to destroy and to protest. A wrecking ball, flying towards a wall, a pebble, flying over the fence. The stone in its flight acquires the ability to not only demolish buildings, but social orders as well. The myth of David and Goliath serves as an eternal reminder of this power.

Stones make cracks, but stones themselves also crack , forming rifts and holes. These cracks may be seen as a doorway, a portal; an absence that turns into a presence. These entrances to large rocks and caves were human’s first shelters, shelters that they would continue rebuilding millenia to come.

In the crevices of the smallest stone we will find traces of life; imprinted there are thousands of years of world dynamics, terraformation, cataclysms and ancient creatures. These cracks in the stone refer us back to the elements and energies formed in the beginning of our universe. Stone radiates energy and movement and the forms from which they are built reradiate those energies.

Stone is not only a solid, rigid material through which we interact with eternity, but also a source of continuous change

Unlike concrete and metal, stone is never dead, but always alive. When a stone building decays, it returns back into the landscape, the construction cycle closes and begins anew. History has also witnessed stones that were used in the construction of multiple buildings throughout the centuries. Taken out from one wall, they found new places in others – in structures, in religion practices, in traditions – in this way, stones are embracing, not imposing. Stones are taken apart, stacked, and rearranged anew. They are never waste, but always a source of material.

Stone ruins invite a comparison to human memory - similar to stone, it is full of cracks and caverns. We excavate it again and again in an attempt to construct something new from the remnants of the past. While this excavation leads our thoughts back to the past, what if we look at the ruins and try to see in them an image of a more sustainable future?

Perhaps what the world needs now, as we sink deeper and deeper into an ecological crisis, is a New Stone Age. There is a need to reclaim the wisdom of stones, also known as “lithosophie.” Lithosophie invites us to look at stone not as luxury, but as a commodity, not as decorative, but as structural material. “The perfect imperfection of stone" is juxtaposed with the uniformity of concrete and metal. Its production leaves a significantly smaller hydrocarbon footprint and provides working places for humans not machines. As, so far, not a single machine can compete in the art of laying stones with a real mason. The philosophy of the New Stone Age is for those that strive to preserve human reference in whatever they build.

And so it seems, the phrase from the book of Ecclesiastes "a time to scatter stones and a time to gather stones" describes the structure of life itself. Stone is both eternity and eternal change, both material and instrument, within which movement and immobility are linked in a dialectical pairing of creation and destruction. Stone is not diachronic but synchronic: it holds the secrets of the past, influences the present, and awaits the future. It is a symbiotic companion of humankind, which, as it provides us with protection and support, tells us more about ourselves through its silence than anything else in nature.

Text by Konstantin Koryagin