Nawal Nasrallah’s work as a culinary writer and scholar has been critical in preserving historical recipes from the Islamic world. Thanks to her translation of Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from Al-Andalus and Al-Maghrib, readers can now enjoy unique recipes from the 13th century that reflect the values, interests, and culinary tastes of their time. Anthropologist Stefan Williamson Fa speaks with Nasrallah about her latest publication, unexpected ingredients, and the legacy of Al-Andalus.

In the tumultuous era of the early 13th Century, as Christian kingdoms waged military campaigns against the Muslim ruled regions of the Iberian Peninsula, a significant cultural exchange unfolded amidst the upheaval. Muslim refugees, compelled to flee or forcibly expelled from the Peninsula, carried with them the rich culinary traditions cultivated over centuries in Al-Andalus, the Islamic Iberian realm. Amidst this diaspora, Murcian scholar Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī (1228-1293) undertook a monumental task: to preserve the intricate gastronomic heritage of Al-Andalus. In his exile in Tunis, around 1260, al-Tujībī meticulously compiled a compendium of recipes, culminating in Fiḍālat al-Khiwān fī Ṭayyibāt al-Ṭaʿām wa-l-Alwān, Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from Al-Andalus and Al-Maghrib—one of the rare surviving cookbooks from that era.

Now, in a remarkable feat of scholarship and culinary investigation, U.S.-based Iraqi culinary writer and scholar Nawal Nasrallah has unveiled these forgotten recipes with her recent English translation of al-Tujībī’s seminal work. Available in paperback through Brill, Nasrallah's translation not only offers a window into the gastronomic past of Al-Andalus but also presents an opportunity for contemporary readers to rediscover and savor these culinary delights through its recipes.

The feast lasted for several days. Soon after the circumcision, celebrations commenced with first serving droves of the highest in rank endless varieties of foods, and they ate and ate to their hearts’ desire, with servers swatting flies away from their foods with elaborately decorated swatters. When this group was done, they went to another hall where they cleansed their hands and anointed themselves after being sprinkled with rose water. Then followed droves after droves until the last group, the commoners, entered. They were treated to foods they had never seen or tasted before, and the text uncharitably describes how they hurriedly devoured, gulped, and swallowed the food.

On a social level food was also a cultural touchstone in explaining the human bond between teachers and students for instance. Some of them we learn were reported to have offered daily meals to them at the end of the day’s teaching sessions. Hearty dishes would be served, like tharīd mounded with lamb and sweet olive oil; meals that would keep them full to the following day, one of the students reported. On the other hand, food was also a gauge in demonstrating the collective habits of people of Al-Andalus, such as being fanatics about cleanliness; some would rather spend the little they had on soap than on food. They were also known for leading frugal lives, that is being careful with what they had now to spare themselves the indignity of asking later. Understandably, Al-Andalus was not the Arabia of the legendarily generous Ḥātim al-Ṭāʾī. Extreme winters, snowstorms, famines, and the like taught Andalusis to be reservedly generous and economical with what they had. This is clearly reflected in some of the medieval Andalusi proverbs that survived, such as “If your oil falls into flour, make cookies with them,” or this one, “Do not throw out the water you have until you find water.”

"If your oil falls into flour, make cookies with them"

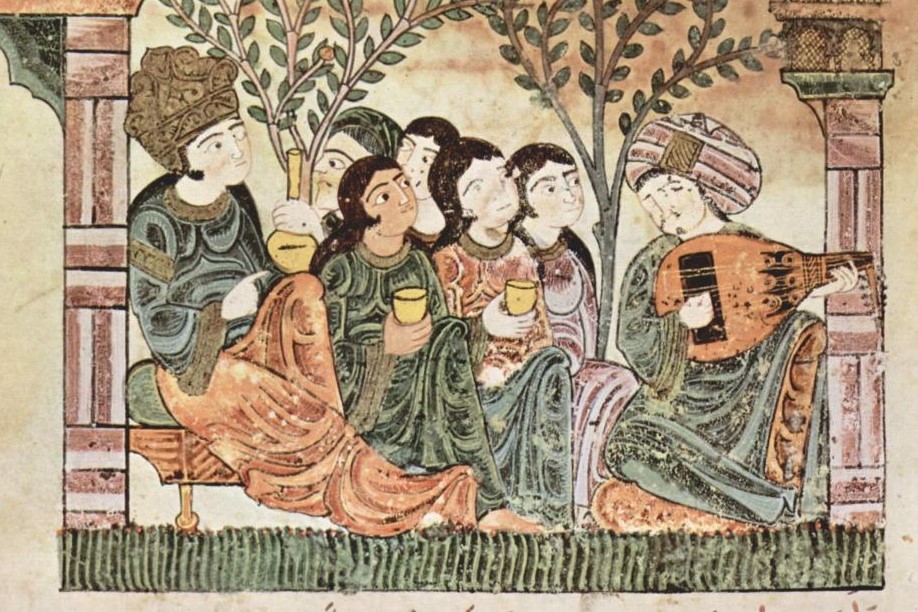

Additionally, the culinary landscape of the western region of al-Andalus and al-Maghrib reflected a diverse and pluralistic society of ethnic and religious communities that found in food a viable common ground for a vibrant collective culture. Muslims, for instance, used to celebrate Christian and Jewish festivities, such asʿĪd Yanayyir, the New Year in the Christian calendar. Interestingly, one of the paradoxes of Muslims sharing the land with Christians in Al-Andalus was that the important religious feast of celebrating the birth of their own Prophet Muhammed only became official in the thirteenth century when the conservative Muslim jurists wanted to replace Muslim celebrations of the Christian New Year, ʿĪd Yanayyir, with ʿĪd al-Mawlid al-Nabawī, the birth of the Prophet. It was a happy occasion, which people celebrated by lighting candles, having food and treats, each according to their own means, wearing their best clothes, and going out on picnics in parks. The wealthy among the jurists used to hold feasts for friends and offer meals to the needy. Poems in praise of the Prophet were recited, and schoolboys used to ask their parents to buy candles to gift them to their teachers. It used to be that men and women celebrated the event together, as they were used to doing with the rest of their feasts, but this was frowned upon by the jurists, who considered this bidʿa (unwelcome new Muslim behavior) that had to stop.

Food also was a popular source of entertainment in their social gatherings and a vehicle for light social criticism. Those to whom food was the love of their lives would declare:

Spare us the ways of lovers, their passions, and rendezvous.

Weep less on their relics, and do not despair when they leave.

It is not the cheeks and eyes of the beloveds that rational men would please.

More joyful to them is thurda of tafāyā with a plump young chicken.

But there were also those with whom such overindulgences did not sit well:

You who eat whatever you crave,

Cursing doctors and their cures.

Know that you will reap what you planted.

Generally, the kind of cuisine that developed in Muslim Spain was considerably influenced by the Mashriqi cooking styles, especially in its early formative stages. As you mentioned, it was propagated by the famous musician Ziryāb, who fled Baghdad around 809, when the Abbasid gastronomy was flourishing. He eventually became the chief singer in the court of the Andalusi Umayyad Emir ʿAbd al-Raḥmān II in 822, where he set the grounds for a richly elegant cuisine. He was credited with “inventing” a green variety of a dish that Andalusis called tafāyā. A plain-tasting dish like tafāyā was in fact already well-known in the eastern region, Al-Mashriq, albeit under a different name, isfidhbāja. According to the Andalusi records at the time, Ziryāb was the one to introduce some splendid varieties of the Arab staple tharāʾid (bread sop), which was in fact known even before the spread of Islam. In addition, dishes made with meatballs, which the Mashriqi cooks called mudaqqaqāt were more commonly known as banādiq in Al-Andalus, they survived, the dish and the etymology, in today’s Spanish albondigas. It is also claimed that it was Ziryāb who introduced the Mashriqi stuffed pancakes (qaṭāʿif maḥshuwwa). Such dishes in addition to the syrupy fritters zalābiya, and the savory tharīd and the grain porridges like harīsa, and the various meat stew dishes, all these retained their appeal for the Andalusi palate.

There were other Mashriqi dishes, however, that went through a “sea change” in the hands of the Andalusi cooks, such as the sweet and savory jūdhāba, which, as we know it from the Mashriqi cookbooks, was composed of a sweet casserole of thin layers of bread, baked with a chunk of meat suspended above it. The jūdhāba we encounter in Al-Andalus had become more like the basṭīla (bastilla), the signature dish of today’s North African cuisine.

Therefore, the eastern element is just part of the story. There are many more dishes for which we have no Mashriqi parallels; they were the ones that developed in the region in an attempt to adapt to the nature of the new land and its climatic conditions. Figs for instance, replaced the familiar dates of the east in making vinegar. Almost all the dishes, and even desserts, were cooked with olive oil rather than the sesame oil and sheep-tail fat (alya) ubiquitous in Al-Mashriq. Hare and rabbit meat was common, and tuna fish was consumed, fresh and salt cured; the latter was called mushammaʿ, whose name survived as mojama in today’s Spanish. Additionally, dishes had to be adjusted to accommodate to the cold weather in Spain. Thus we witness a much bolder use of garlic, which must have been encouraged by the dominant medical opinion that it was beneficial to people living in cold regions. The Christian New Year was celebrated by all by cooking thūmiyya (garlic dish). Also unique were the several Amazigh dishes, as in Ṣinhājī (the precursor of the Spanish olla podrida) and of course kuskusū (couscous), as well as the popular cheese pastries called mujabbanāt, made with excellent varieties of fresh cheese brought from the pasture of Al-Andalus.

There were other Mashriqi dishes, however, that went through a “sea change” in the hands of the Andalusi cooks

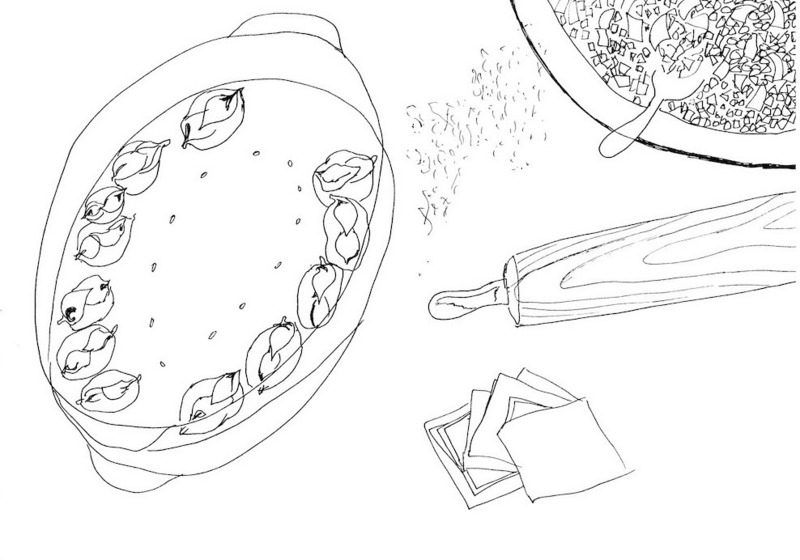

The huge number of chicken recipes in the Andalusi books is also testimony to their popularity and availability. It was in the Andalusi countryside that chickens were raised on a large scale for meat and eggs. The farmers followed simple methods for propagating large numbers of chicks by means of artificial incubation. The availability of eggs consequently gave rise to a cooking technique called takhmīr, which is specific to the Andalusi cuisine. Almost all dishes with little sauce in them were topped with a whipped egg mix in the last stage of cooking.

Unlike the eastern Mashriqi cuisine, known for incorporating fruits into stews and other dishes, only a few recipes in al-Tujībī’s book use apples, quinces, raisins, and dried prunes, which Andalusis called ʿayn al-baqar (cows’ eyes). This is also the case with juices of sour fruits. Mashriqi cooking, especially Egyptian, used plenty of acidic fruits to sour the dishes, the most important of which were juices of lemons, nāranj “sour orange,” utrujj “citron,” pomegranates, unripe grapes, and sumac. The Andalusi cooking by contrast had no interest in such juices; vinegar and murrī replaced them. These are differences that were not dictated by taste as much as by the necessity to adapt to the nature of the place where one lived. In the case of Egypt, for instance, due to the humidity and putridity of its air and heat, consuming foods and drinks with cold properties, which all these sour juices have, was the right thing to do. On the other hand, Iberia, with its moderate weather verging on cold and moist, food was better served with seasonings that aided digestion with their hot and dry qualities, such as the fermented sauce called murrī and vinegar.

One last unique aspect in the Andalusi cooking worth mentioning is the persistent use of coriander, both the seeds and the fresh herb cilantro in almost all the savory dishes, instead of parsley dominantly used in the eastern region. There is no clear explanation for this preference, but most probably because they believed that coriander (seeds and cilantro) aided digestion. In fact cilantro and coriander seeds stamped the Andalusi cuisine with an unmistakable character so much so that it played against them later during the Inquisition trials.

A recipe also comes to mind where the game birds turtledoves are roasted while dangling skewered through their beaks; they are also oven-cooked encrusted in salt in another recipes—a thought for food.

They say it comes from Arabic culture. For me it does not make sense because the Arabs do not eat pork and you use lard in ensaïmada. The story is that it comes from the Arabs or the Hebrews. But it is not confirmed. It is a supposition.It is a supposition.Madeleine Morrow, “An Island’s History is Coiled in a Pastry,” Boston Globe, Jan. 1, 2016: G9.

Andalusi Muslims and Jews did indeed bake pastries similar to ensaïmada, and they called them musammana after the name of the fat used in layering the dough, which is samn “ghee.” A variation of musammana was layered with rendered suet, which is shaḥm in Arabic, a general name for solid fat and the origin of saïm in Hebrew. The suet used was, as expected, taken from sheep or goats. Muslims were able to make it either way, but Jews made them with ghee only because shaḥm is not Kosher. So it is not a “supposition” but a fact. It is only after the Inquisition that Jews and Muslims who converted to Christianity started using lard so that they would not be suspect.

It is my hope then that by making accessible a “real example” of the culinary cultural exchanges that took place when the Arabs ruled Iberia, as is Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī’s Fiḍālat al-khiwān, that we get a more solid grasp of what happened in the Andalusi kitchens, its perseverance in face of adversity, and what was left behind and what survived in today’s Spanish cooking. The culinary tradition of Al-Andalus, on the other hand, successfully survived in the numerous cities in North Africa, especially Fez, the refuge for the Muslims and Jews who escaped the persecution of the invading Christian armies and the Inquisition. It was a dish like the sweet and savory jūdhāba chicken pie, for instance, that gave the kitchens of al-Maghrib what is now called basṭīla (bastilla) in Morocco, for which it is renowned, with regional variations in Algeria, and Tunisia. And the legacy extends beyond the dishes; a book like al-Tujībī’s is indeed a rich reservoir for the material culture that flourished at the time, and a linguistic one.

Generally such books were not regarded as a form of high literature; to biographers and chroniclers at the time they were not considered mention-worthy, unless perhaps those written by famous personages. But on the street level, they evidently were sought-after commodities, read and used by apprentices, perhaps professionals at cooks’ shops, who I imagine would leaf through such books in search of some new and exciting ideas, and by hired household cooks to impress their masters, as we learn from one of the recipes in the Egyptian cookbook which describes how to perform magic with fruits by writing on them. "Surprise your master," the recipe excitedly suggests, "with a plate of lusciously ripe fruits with verses inscribed in green on them, and you will be in his good graces."

With the increasing numbers of the Iraqi diaspora that fled the ravages of war in our homeland, I felt the need to document and preserve the Iraqi culinary heritage I grew up on.

With al-Tujībī we are on a bit firmer ground. From his biographers, we learn that he was born into an affluent and well-established Andalusi family in Murcia, and that al-Tujībī himself was a well-known scholar. However, not a trace do we find of his gastronomic achievement nor the cookbook he wrote in his biographers’ accounts. Therefore, once again we have only his cookbook to answer the question as to why he wrote it in the first place, and for whom. There is no indication in al-Tujībī’s introduction that he was commissioned. Most likely he was motivated by the desire to preserve the Andalusi cuisine he knew quite well from his years growing up in Murcia, where he led a life of luxury. A cuisine he cherished was in danger of being forgotten or lost, with multitudes of his countrymen fleeing Al-Andalus like himself. It is in this regard that I see al-Tujībī as a kindred spirit. With the increasing numbers of the Iraqi diaspora that fled the ravages of war in our homeland, I felt the need to document and preserve the Iraqi culinary heritage I grew up on.

In addition, given al-Tujībī’s literary credentials, it should come as no surprise that he advocated the notion that recipes can indeed be read for entertainment as well, and in this he was ahead of his time. At the end of one of his chapters he declares:

What I have mentioned of the varieties of . . . dishes above should be sufficient, God Almighty willing. Still, even though most of them might hardly ever get to be cooked and tried, including them will indeed rarely fail to please with their novelty and exquisiteness. This is also true of most of the other chapters in this book.

I here state that in the field of cooking and whatever is related to it, Andalusis are indeed admirably earnest and advanced despite the fact that they started later [than people of Al-Mashriq] in creating the most delectable dishes, and in spite of the constricting limitations of their borders, and their proximity to the abodes of the enemies of Islam.

This came as a justification for the negative attitude he expressed towards the Mashriqi style of cooking as represented in their cookbooks, that it “does not sound palatable to the ears” and which people of Al-Andalus find “deplorable, even filthy; but to them it is the most elegant of foods.”

I will venture and introduce him to the New World produce, such as the potatoes, tomatoes, and chili pepper. Perhaps he would not relish the stews I will offer him reddened with tomatoes, but the potatoes will pass, I expect. I also expect he will enjoy the kick he would get from the chilis. Also, since he was so prejudiced against the Mashriqi dishes of his time, I will make for him one of al-Warrāq’s 10th-century dishes from Baghdad, a feat which involves roasting a lamb which has been variously stuffed in the belly, the hind legs and the fore legs. The recipe proudly ends with the following statement:

When you present it at the table, it will be as if you are serving five different dishes, each of which with a specific delicious taste and aroma. What’s more, the racks will be offered as tasty plain meat, God willing.

I bet he will be impressed. Hopefully it will change his mind about how we Mashriqis have been cooking our foods.

Nawal Nasrallah's translation of Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib: A Cookbook by Thirteenth-Century Andalusi Scholar Ibn Razīn al-Tujībī (1227–1293) is now out in paperback via Brill.