The essay by curator and writer Su-Ying Lee was originally published as part of A Matter of Taste, an online exhibition curated by Letticia Cosbert Miller, designed by Natasha Whyte-Gray, and presented by Koffler.Digital, a program of the Koffler Centre of the Arts. A Matter of Taste features original work by twenty one artists and writers, each exploring the topic of food and the cultures that surround it.

When I was around six or seven years old a white man thought to take my photo. As he raised his camera my mother moved in front of me to block his view. He, like many white hobby photographers, along with fledgling art students in the city, equated Chinatowns with lens titillation. Whenever we went to Chinatown, my mother bought my favourite treat: duck feet from King’s Noodle, a Cantonese style BBQ restaurant. A salty rich marinade permeated the skin and webbing of the duck foot, a cut of meat I appreciate to this day for its textured complexity. Knowing the enjoyment that this food brought me, my mother had unwrapped the paper take-out bundle outside the restaurant and handed me a piece. It was at this very moment that I noticed the would-be photographer, my attention drawn away from the snack in my hand by the feeling that his intentions were wrong.

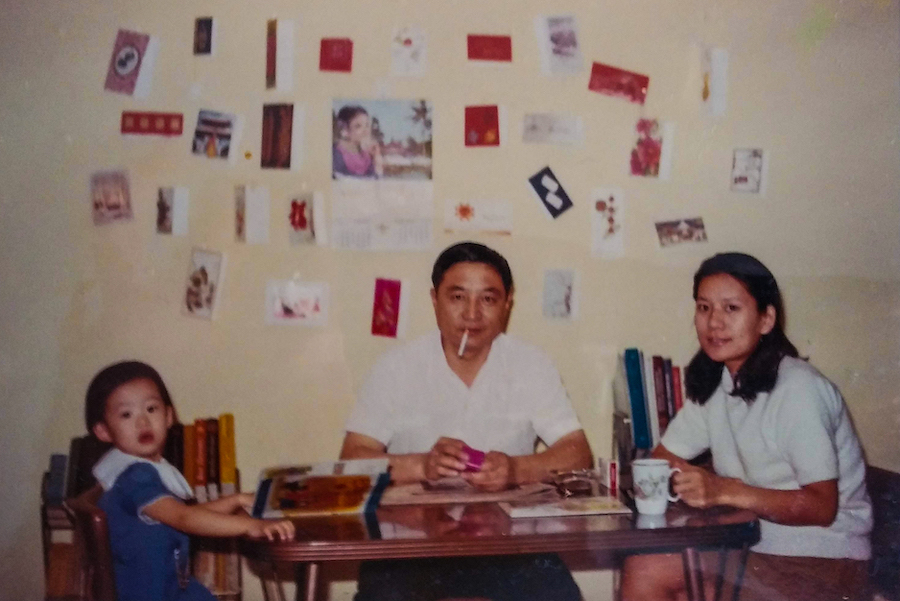

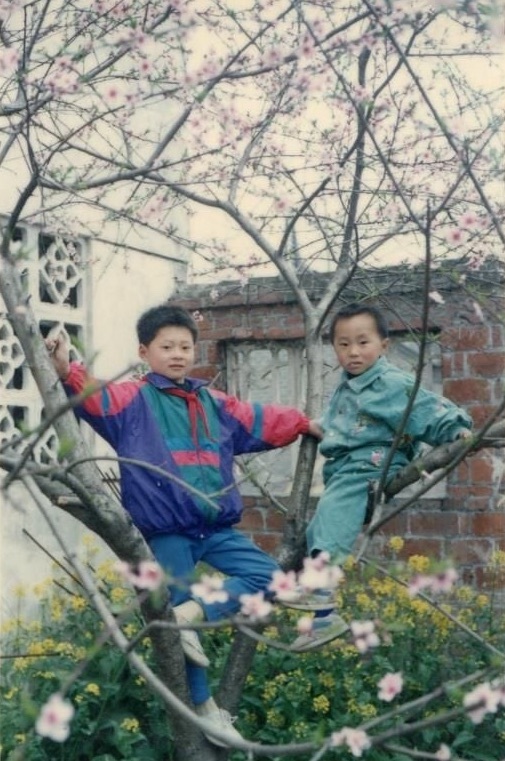

My father (Bàba/Bà) was from Northern China where foods made of wheat flour are commonly eaten. Throughout my childhood, I spent many weekends making batches of plain, stuffed and green onion spiraled steamed buns or dumplings filled with pork and vegetables. We snacked on green onion pancakes as we waited for dough to rise or parcels to steam and boil. Every step was done by hand—mixing and kneading dough, rolling out each skin, finely chopping vegetables, seasoning ground meat, forming buns and pinching dumplings closed. My dad’s eyes were joyful as he taught me and my brother the techniques of pleating, and the chemistry of yeast, water and flour, good-naturedly teasing us as our clumsy hands attempted the crimps for enfolding meat within dough. Although the types of dough used to wrap bao zi (stuffed buns) and dumplings differ, both are prepared for filling with the same method. Bà would form the dough into a long roll that was then cut into smaller sections, and, finally, alternating between using his fingers and his red handled rolling pin, he worked the pieces into rounds. The rolling pin had seemed intimidating for its heft and for the finesse that was required to produce well-made rounds. Several years ago, in a thrift store, I found the exact same rolling pin and saw that it was a solid, simple tool, but not unwieldy as I had perceived it to be in childhood. As a young adult, I considered dough fussy so I had never anticipated needing such an object, but being drawn to its familiarity, I bought it. Finally, after finding the texture and flavour of store-bought and restaurant steamed buns unsatisfactory, I surrendered to making them myself. Now regularly used, I value the rolling pin for more than just its utility.

Prioritize fresh produce, buy what is on special that week, stock up on non-perishables when they are on sale

Come Monday, the weekend’s cache of food would be packed up for our school lunches, much to the dismay of my primary school classmates. “Ewwww! What is that? It smells! Look at what she has!” are the childish screeches in my recollection that turned the lovingly made foods leaden and burdensome. This was my experience growing up in the 70s, when the complexly textured cuts of meat I adored, including duck and chicken feet, cow’s tripe and pig’s ears, were still cheap and the suburb my parents moved us to was white as Wonder Bread. To memory, I only ever had one friend over for a meal. I remember the confusion I felt seeing Darrin halt at the bowl of congee my mother set before him—unable to eat this mildest of foods, nor the accompanying pickled vegetables. I certainly wouldn’t have invited other children over after seeing what I considered to be unappreciative wastefulness.

Prioritize fresh produce, buy what is on special that week, stock up on non-perishables when they are on sale, my mother advised. At that time, bones were treated as a near valueless by-product of butchery, making this foundational ingredient for comforting soups inexpensive and plentiful. Until I reached the age when I would grocery shop for myself, I had only known rice to be sold in the economical eighteen-pound bags that were ubiquitous in our home. My mother preserved foods herself. Pàocài (spice infused lacto fermented pickles) and garlic chili oil standout in my memory, and remain foundational flavours for me and a constant in my own home. Besides her lessons on economical shopping, the most notable imperative was to never, EVER, waste food. Not even one grain of rice. We rarely ate out. With admonishment, my mother told me that Canadians were wasteful with food and money. She had known true hunger and deprivation growing up with many siblings in Taiwan post WWII, through the Taiwan Strait Crises and martial law. Childhood hunger had made her resort to foraging for plants to eat, on occasion with terrible outcomes. When people asked her how she stayed thin, flippantly or perhaps out of remembrance of trauma, she answered, many generations of starvation. Preserving food, foraging, and remarkable thinness would never be romantic activities and ideals to her, although they have become so in a segment of North American culture. My father once told me that there was a type of minerally dirt that is edible. He never told me how he knew this. For both of my parents, resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and conservation were ways of living informed by personal survival.

I have come to appreciate the importance of having a sustained relationship with a food, and the cultures that form it, to achieve the best preparation

Once I reached adulthood, I still ate out infrequently due to a combination of ingrained family values, my low art-worker salary and my budget limitations as a single parent. On one exceptional night I went to the new most buzzed about “meat-forward” restaurant. They served offal with bravado, which was then the trend. Around this time Western chefs also began to tout the use of bones. Bone-broth was revealed as a new health-food discovery, and marrow bones were being carefully plated at trendy restaurants. At this particular restaurant, I was eager to try the pig ears. It was surprising to see this childhood favourite, a food previously invisible or shunned in North America, on their menu. I imagined a savvy chef’s tasty new preparation for the old favourite, but instead a scant plate of woody, difficult to chew, deep-fried strips arrived at our table. The cut of meat’s ability to retain deep flavours and the pleasure of its layered textures, at once tender and crisp, were entirely lost. This is too steep a price to pay for our cultural foods to enter the mainstream. Since then, I have come to appreciate the importance of having a sustained relationship with a food, and the cultures that form it, to achieve the best preparation.

As a mother, nourishing my child was a fundamental comfort. If he experienced joy from the meals I made him, then my single-handed parenting had achieved a critical foundation of care. Both the economy and the pleasure of my parents’ kitchen have been imprinted upon me and are now my son’s inheritances. During the social distancing of the COVID-19 pandemic, my son mentioned that he was helping his roommate cook. As many of us experienced over this unusual episode in our lives, his roommate was lacking energy or motivation and as a result, found himself with groceries on the edge of spoiling. I was immensely proud of knowing that my son has the life-skills to care for himself and for others. He went through the familiar phase of requesting the foods he saw in his schoolmates’ lunches, but, ultimately, in adulthood his preferences are for the foods and flavours of our home cooked meals. Like me, one of his favorite foods is pig ears. My son regularly grocery shops with me in Chinatown. Chinese grocers attract those among us who know how to coax the most flavour out of foods—from a variety of cultures. In an aisle of dried and fermented items a middle-aged woman with a West Indian accent turned to my son, picked up a package of goji berries and sighed “I hate when white people start buying something and they make it expensive.” A moment of commiseration between them.

The reality of racism and privilege is that people will selectively decide to enjoy parts of a community’s culture without standing against that community’s dehumanization

It was interesting to see how some who had likely neither experienced extreme scarcity first-hand, nor lived with the legacy of it, responded to emerging news of the novel coronavirus. I remember seeing the self-satisfied faces of people coming out of the supermarket with stacks of toilet paper. Even though I followed the developments since they began, it never occurred to me to hoard anything as useful as food, much less toilet paper. As I watched the price of toilet paper triple in price, I realized that in the space between living a life of casual wastefulness and fear of a societal shut-down, the first instinct of some was to prepare for dealing with their own literal waste. In truth, society has functioned poorly for many long before the novel coronavirus—the disabled, chronically ill, racialized, unhoused, elderly, and under-waged for whom the pandemic has compounded inequity to a sometimes fatal degree. How could toilet paper be mistaken for the priority?

COVID-19, and the social isolation that it has created, has accelerated and intensified the rate at which we cycle through food trends. Under these extraordinary circumstances, even low-carb and gluten-free diets have fallen out of fashion. Along with baking bread, I’ve noticed popular food media outlets and individuals displaying their versions of congee, green onion pancakes, hand sliced noodles, and more. They suggest these as recipes for passing time, nourishing bodies, and providing pleasure. It is not unusual for cultural recipes to be presented by white folks, frequently without attribution to how they learned of the foods and ingredients. I don’t admonish them for wanting to make our foods—they are delicious—but the reality of racism and privilege is that people will selectively decide to enjoy parts of a community’s culture without standing against that community’s dehumanization and may even actively participate in it.

Unflinching images of foods that are less understood under conditions of white-normativity, confront and challenge racist beliefs that would define what is edible

I have also posted photos of my meals during this time, and how they were made, on social media. Sharing cultural recipes is not my intent. These posts are a nod to my kin. I am communicating that, for us, these are foods that have always been here. Besides, I believe that unflinching images of foods that are less understood under conditions of white-normativity, confront and challenge racist beliefs that would define what is edible. The fascination with what racialized people eat looms with a particular determination at this time often resulting in either appropriation or demonization. For this reason, I see us as standing together in defiance: Xuan and her braised pig’s feet, Amy and her hot and sour soup, Alvis and their Hong Kong cafe macaroni, Jane and her Hainanese chicken rice, Alvin and his jian bingjian bingTraditional crêpe-like street food served with various fillings and sauces., and Shellie and her chong you bingchong you bingSpring onion pancakes.

.

One theory is that COVID-19 was transferred to humans from an animal called a pangolin that was for sale in a wet market in Wuhan, and that the pangolin caught the virus from a bat living in the woods near-by. This theory has been distorted to support Sino-phobia and racism and violence have been directed at anyone who is perceived to be East Asian. An unrelated video of a Chinese influencer trying bat soup during a 2016 trip outside China has been instrumentalized to fit the demon narrative. I purposely omit the location of the bat soup tasting because I will not satisfy the alienating gaze that some readers will seek to level against the country that the dish originates from. At present, a largely uninformed, international outrage calling for wet markets to be banned globally advances hand-in-hand with the exotification of what people in China, and beyond, eat. Racism bulldozes over and misrepresents many facts about wet markets and the communities that use them. Seeking to exert control and judgement over what racialized people eat and where they get their food is white-supremacy. Taking credit for recipes from other cultures is cultural appropriation. A white man photographing a Chinese child eating a duck’s foot in Chinatown is exotification and racialization. When my mother put her body between the photographer and I, a simple shift, I gained an early insight into image making, refusal, and agency. It is with this comprehension that I have navigated through the crush of images and information released throughout the pandemic.