Amsterdam-based artists Metahaven employ a variety of tools, concepts, and tropes to reveal the poetic potential of the mutations humanity has been going through. In its inaugural issue Home, EastEast had a chance to present an exclusive online screening of their two-channel film work Hometown (2018). Researcher and EastEast editor Lesia Prokopenko spoke with Metahaven’s Vinca Kruk and Daniel van der Velden about their work and the world it inhabits.

“Before we continue, let us agree on the time,” suggests the protagonist of Metahaven’s 2018 film Hometown. But the station clock’s noon, “made out of one and two,” happens to be three—moreover, we later find out that “the station clock came to a standstill, it’s always the same hour.” Our only chance to synchronize is to become attuned to the dream-like logic of unmeasurable time and ever-changing space.

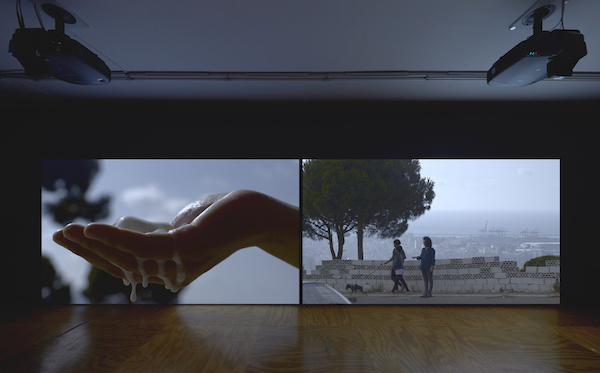

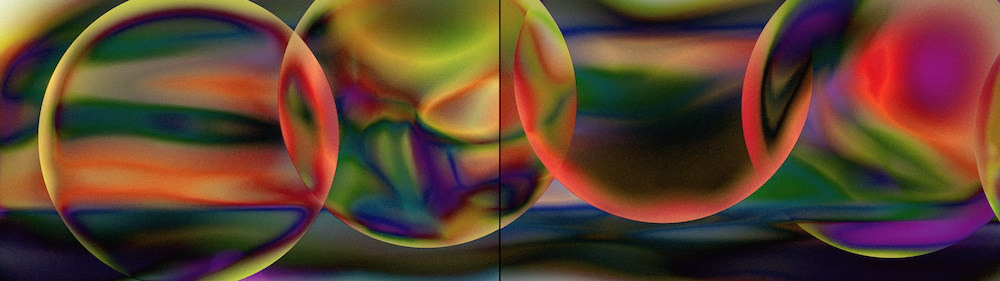

Hometown was shot in two different cities located in the same time zone, only five degrees of longitude apart. One of them is in Western Asia while the other is in Eastern Europe. The narrator-protagonist of the film has two faces and two voices, represented by the names of Lera and of Ghina. Perfectly entangled, they aren’t and yet are the same person. The environment they inhabit is woven from the loosely identifiable cityscapes of Kiev and Beirut, welded together by the oil-spill rainbow of viscous animated insertions, by shadows and the glare of the sun “hiding in moonless blue.” Ghina sets a time and place for a meeting: “I’ll see you at dawn where the road splits in two,” arriving there alone to encounter herself in a joyful dance.

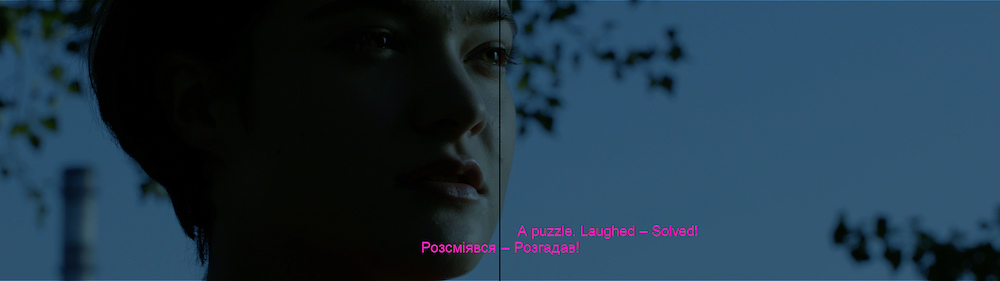

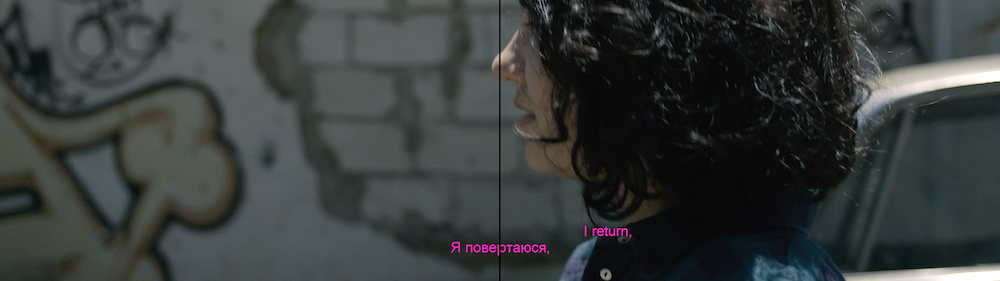

A fictional “forgotten city, forever remembered” is the only possible homecoming destination. Home is a dimension that always needs to be discovered anew. At any given point, there is nothing more concrete and nothing more elusive. A hometown keeps constructing itself around you in your sleep, and you never wake up to the same world as the previous day. Home is always both of the future and of the past: “I return to where I never lived before.”

What, then, is in the present? Deliberate ice-cream leaks, pixelated real-life lemons (for the shoot, they were roughly peeled to resemble badly rendered digital imagery), a shanzhai plastic bag with a BMW logo spelt “WWW” (found by chance at a Ukrainian market). The present is a cunning trick, a fleeting diffraction of matter and data. To embrace its absurdity is the only way to reach a moment of clarity. In another serendipitously filmed sequence, Lera comes across a white butterfly and demonstrates what one is to do with this newly emerged fragile sense: grasp it gently and set it free.

Why angel-like? Because of the cuteness and the anarchic innocence. We’ve written elsewhere that “a child’s first speech acts do not consist of words so much as sounds. We measure the result that these sounds produce by something other than their effectiveness at transacting. While we tend to live by a working agreement that things in the world correspond to their names, we rejoice in a small person voiding that agreement.” Language in a child’s world is always in the making, and children often take language more seriously than adults do. Even when they become aware of the system of (social) rules and contexts that people use to give value to statements, they may ignore it. Adults often manipulate their message to get a point across, and in doing so violate whatever brittle contract existed between language and reality in subtle yet essential ways. For example:

Y (me, waiting at a red traffic light, with X, on a bike):

“Ah, this is taking forever.”

X (six years old):

“No, it’s taking a few minutes.”

The key operation of some of the proto-absurdist perevortyshi (turnarounds) and their predecessors, nebylitsi (neverhoods) is about putting things together that don’t match, that contradict each other, about putting them inside the “wrong” kind of logic. This combination is intuitively funny and in a certain sense true: more true than their forced separation into sense and nonsense. Because these rhymes do not exist in a vacuum, they can be read as political; they always prevent some centralized version of reality from appearing to (or claiming to) make perfect sense. They were deemed politically suspect during a regime and during a time that was obsessed, like ours, with “realism.” Chukovsky was accused of inaccurately portraying the lives of crocodiles; the OBERIU authors were, in their autonomous poetry as well as their works for children, persecuted for political agitation.

Our receptiveness to this poetry does not make us experts. There is a long way from loving to understanding, and we are somewhere on that road. Right now, precisely, we are in the mid-eighteenth century, trying to understand an anonymous poem from that time that already appears to exhibit many of the traits that can be found in works from the twentieth century.

It seems that the emergence of absurdist poetry in Russia, while not exactly an isolated process, took place along distinct paths. In part, it seems to have branched from a nomadic, satirical folk tradition linked to the carnivalesque, which was at odds with the formation of a centralized Russian empire and the increasingly central role of the church. But there are also mystical aspects to it—not necessarily in opposition with the carnivalesque―that relate to apophatic religious statements.

This tradition was then also cross-pollinated with influences from France, Germany, and England.

In the second half of the twentieth century, folk absurdism became a subject of scholarly observation and scientific study, at least in the West. Chukovsky’s From Two To Five was widely read in English. The folklorists Iona and Peter Opie coined perevortyshi as “tangletalk,” indicating how it entangles its utterer in an impossible proposition. Politically, it remains an intensely networked body of work. Indeed, Pussy Riot cites Vvedensky, but they also cite Nikolai Berdyaev—both, with all their differences considered, could be seen as mystics. The subtle possibility of mysticism, of holy fools, is almost never reproduced in the narrative that seeks to label absurdism as straightforward political art. Something like OBERIU’s “meaninglessness,” for which its members were persecuted, asks the difficult question of political art to define itself and even the question as to whether such an art can purposefully exist.

The time to which this work belongs has not ended.

The quote from Hometown you mention is honing in on the idea that you do not just inherit the object but that object’s future. Just like Henri Bergson wrote, that “time […] is nothing but space,” Vvedensky wrote of a “shimmering” that occurred when you disregarded the conventional measuring units of time, and looked closely beyond or between them: the measurements-as-names for time’s (and thus of life’s) organization readily dissolved.

Poetic cinema can cross-pollinate the implications between a word and an image and vice versa, and is not determinist, whereas narrative cinema steers a story in one direction and not another. Poetic cinema can potentially appear cyclic, whereas narrative―in which entropy is leading―tends to feel linear. Hometown was made within a tension between poetic and narrative―there are elements of both but rather than being on either side of the division, the film contains pockets of storytelling, like lyrics and a chorus almost.

Hometown could not have been possible without Mhamad A. Safa, a composer, musician, and architect, who at the time operated under the moniker LAIR. The main theme that Mhamad wrote somehow joins into the emotional space of early Detroit techno of Derrick May and Carl Craig—haunting, melodic, and lyrical. For us, it breathes the idea of dawn, of beginning, of the early morning after a night spent excitedly awake. It appears in the film two times: once around the beginning, when Ghina is eating an icecream, and second, when she is jumping on the empty Hamra―Place des Martyrs junction in Beirut, “where the road splits in two.” For us, that scene is about a one-person rave.

The obvious difference with Hometown is that while we are responsible for the structure and narrative of Eurasia, in the latter we cite someone else’s work. The film cites Vvedensky and applies it to a situation that may or may not relate to his work. But we think it does. In particular, “Snow Lies” appears at a moment that we are in Karabash, a copper smelting town near Chelyabinsk, and there are mountains of black slag and mountains where nothing grows in the sulfuric and arsenic climate. That devastated space in which the pastoral and epic functions of nature and landscape are all but dead resonates well with the poem where we may say that, as in other works of Vvedensky and OBERIU, phraseology is kind of destroyed and turned on its head. In the same way, something new begins in this site of passive geophysicality.

To claim that communication technologies shift our perception of space is to acknowledge the paradoxes, clashes, and overlaps that manifest themselves between planetarity and the enclave. In the same way that nobody has ever seen “The Roman Empire” in its entirety, nobody has ever seen “Eurasia.” Eurasia is a sub-planetary concept called into existence to counter or exist alongside other sub-planetary concepts. It does not tell us anything more than that Europe and Asia are not separated from each other by water.

That being said, while nobody has seen Eurasia, there are instances of Eurasia that can be seen and are telling. During filming, we went from Ekaterinburg to the Kazakh border, first through the heavily industrialized Ural cities and then onward into the empty steppes.

"Snow Lies" (1930) by Alexander Vvedensky

Within the steppes, something peculiar happens to the landscape: an emptying out, “опустошение,” of content, and therefore of what we can call “meaning.” The territory, optically, ceases to be a collection of “things” and ceases to provide orientation or direction. At the same time the steppe is not “nothing,” it does not conform to the idea of either a clean slate or a desert. It empties out, pauses meaning, providing a huge, stretched-out canvas to reconsider what reality is. That this spatial phenomenon manifests itself within the transitional area between (or perhaps: belonging to both) Europe and Asia may be a complex form of environmental coincidence, yet at the same time it translates as a canvas for planetarity. If we’re correct, the artist Anton Vidokle filmed his trilogy on Russian Cosmism in Kazakhstan. Andrey Tarkovsky’s Stalker was originally planned to be filmed in Tajikistan. Through the notion of the Zone―as introduced by the Strugatsky brothers in their 1971 novel Roadside Picnic―planetarity and the enclave coincide. The Zone then contains what cannot be explained or claimed by the surrounding “normal.”

Even though some of the key scenes in Eurasia are about this stretched-out canvas and the pause of meaning, the political impetus of Eurasia is not neutral.

Commonly held space of difference, like the Eurasian steppe, relies on an always-unfinished practice of translation which is precarious and error-prone. The artist Natalia Papaeva has created what is to us a very striking performance work, titled Yokhor, consisting of a lullaby from the Buryat Republic. In it, the artist is desperately repeating―over and over, first singing, then shouting―the words she remembers from the lullaby, not only hinting at but embodying the disappearance of the Buryat language. Here, Papaeva is doing something more than representing Buryat culture on the world stage; she is embodying the vector by which that culture becomes untranslatable, by which it is becoming exempt from finding words. This points us to the limits of the presumption that we are all simply involved in reperceiving space through digital tools. The act of translation, always one of curiosity and restraint, itself depends on the availability of a live original.

The very tools of our translation―such as Google―are now also tools of our blindness. To your question, the rise of far-right nationalist politics across the board, as is the case in the political concept of Eurasianism, appears to be almost a function or even a pathology of the software platform. In a purely materialist explanation of these politics, getting low-cost scalability for a heretofore quite obscure political program has never been easier whereas this program’s common systemic opponent―multilateral liberalism―has never been more vulnerable.

One coincidental element of the Zoom Cinema prompt is that many of its outcomes came to look like the Hometown setup, as in two 16x9 aspect ratio moving images next to each other.

I have returned there

where I had never been.

Nothing has changed from how it was not.

On the table (on the checkered

tablecloth) half-full

I found again the glass

never filled. All

has just remained just as

I had never left it.

Sono tornato là

dove non ero mai stato.

Nulla, da come non fu, è mutato.

Sul tavolo (sull’incerato

a quadretti) ammezzato

ho ritrovato il bicchiere

mai riempito. Tutto

è ancora rimasto quale

mai l’avevo lasciato.

The detail here that does not get fully expressed in the stunning English version appears to be the incerato a quadretti: a chequered tablecloth that is waxed and maybe made of a plastic-like material. Not a luscious fabric, but its cheaper, PVC simulacrum, onto which the monochromatic tartan is printed, not woven.

Our neighborhood grocery delivered fresh vegetables and other delicacies to our home doorstep about every two days while we were in quarantine. We sent them a shopping list as a WhatsApp direct message. Ramis replied, usually within seconds of receiving the message: “Toppie!” After collecting the groceries from his mom’s store, Ramis sent a cashier receipt and a so-called “Tikkie” which is a prompt for our payment.

Ramis appeared with the groceries just minutes later.

During the lockdown many cities became versions of the same empty-looking typology, as if they were Pyongyang or East Berlin: versions of pre-1989 model cities without any significant sense of public life, and therefore looking like what the future used to look like―looking like the past of the future. In that way, the lockdown, which triggered so many support networks through intense affect, via email and overcrowded apps and interfaces, at the same time produced pristine skies with no airplanes and spatial emptiness, looking like a modernist plan, or like a music video. We are still vexed by this relatively brief but decisive phase of standstill.

To us, it is kind of striking how the emotion changes between the two pieces. The emotion in the Elektra sequence is something like “The lucky fact of your existence!” (this is a Shakira quote to be perfectly clear!) The piano, by Kara-Lis, says “I am!” and we agree. But it also echoes the interior voice: “I am responsible.” “I am displaced by the fact of your existence.”

Artwork credits:

Metahaven, Hometown (2018)

31 minutes

Languages: Arabic, Russian

Subtitles: English, Ukrainian

Made possible with the support of Sharjah Biennial 2017, Sharjah, UAE

With special thanks to Ashkal Alwan, Beirut; Izolyatsia, Kiev; Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam

Cast: Ghina Abboud, Lera Luchenko

Director of photography: Karim Ghorayeb, Yarema Malashchuk & Roman Himey

Music: Mhamad A. Safa

Line production: Jinane Chaaya, Tania Monakhova

Metahaven and EastEast would like to thank Walid el-Houri and Amal Issa for the provided information on the ways to support Beirut.