Photography by Sahir Uğur Eren

The work of architect and scholar Ziad Jamaleddine investigates the relationship between public space, religious architecture, and urbanism in West Asia and North Africa and the United States. Architect Nabi Agzamov spoke with Jamaleddine about the concepts of home and public space in the evolving Islamic tradition.

Of course, I live in Brooklyn, New York, with my family. But I also visit Beirut a few times a year, sometimes for extended periods, and stay with my parents or with friends. There, the idea of home is tightly related to the concept of a large, extended family and social network, with much less room for privacy. This is unlike the West, where notions of home and of privacy came to be defined by the nuclear family. Then, when one travels frequently for work or research, they also build affinities for those places. You create a different understanding of home not only by studying forms of living through architectural research, but also by building new relationships with other people at each location.

So, maybe I would say that there is no single fixed understanding of the meaning of belonging or home, that it appears to be different wherever I go. I am constantly crisscrossing between those places and people. For instance, when I am in Beirut, I feel like I'm an outsider who has just arrived after a long trip. When I come back to the States, I suddenly have the same feeling, as if I were arriving here for the first time. Sitting here, I sometimes feel nostalgic about the places I have just left and vice versa. I think that it’s an interesting, constructive conflict: where one is never settled or at complete ease with their environment, or for that matter, able to take it for granted.

To expand on my first answer, there are historical, social, and cultural differences between West Asia and the United States. These differences were reflected most sharply in residential typologies and in the morphology of a so-called Arab or Islamic City, particularly in the pre-modern period. The medieval city was shaped by constraints that had to do with concepts of family, kinship, and community. As Janet Abu-Lughud has described, these cities organized themselves around differing degrees of semi-public and semi-private spaces within their residential quarters (Hara). This stood in contrast to the modern Western city, where notions of private property were spatially and legally distinct from the public domain. As I mentioned before, in the US, the concept of a single-family house was very much the outcome of this division.

Ever since the colonial period—especially with the rise of the nation-state, and with it, the modernizing city—these differences have slowly transformed or dissolved in many West Asian and North African cities. Note the erasure of Kuwait’s medieval center in the mid-twentieth century following the explosion of the oil economy. The mushrooming of a villa, or a single family house, consequent to its adoption as a modern way of living in the newly built suburbs, coupled with the construction of vehicular infrastructure, reshaped the contemporary form of the city.

Today, however, a West Asian city—whether the new emerging cities of the Arab Gulf or re-built cities in places of post-conflict, like in Lebanon or Iraq—is subjected to global “neoliberal” forms of development that have aggressively fragmented and privatized its public spaces. In the case of Beirut, for example, the seafront has turned into a battleground for private high-end residential and hotel acquisition. Here aggressive forms of development threaten the ecological fragility of the coast and erase public access. The same phenomena is seen playing out in the West, whether in Belgrade’s Waterfront development or, more recently, in the Hudson Yards, where high-end residential towers are siloed within new forms of privatized public space.

Finally, I want to end by pointing out that these forms of development, driven by the global movement of capital, have, in fact, never fulfilled the city’s real needs—like housing its local population. Hence, you see a mirrored rise of informal growth, as in the case of Cairo where almost 80% of its housing units are absorbed by the “informal” city. This informal growth fills a critical role and recreates some of the organic communal social structures with complex notions of public and private. And again, in the West, a similar phenomenon seems to evolve on the periphery of the city, especially within disenfranchised minority communities, where the state—the supposed caretaker of its citizens—has failed to provide the social welfare programs that those communities need. Think of the Paris banlieues upheaval a few years back, or of the problem of potable water in Michigan, in the US. There you see similar forms of community development and social solidarity filling the voids left by the state, carried by civil society or even by religious institutions.

Would you say a house and a neighborhood have an important social value in an Arab city, in addition to being simply a dwelling place?

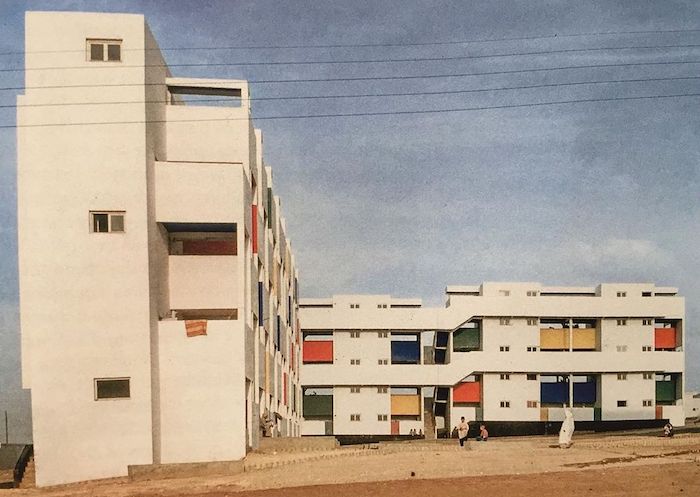

, for example, conducted similar typological experiments with housing, learning from “local forms of settlement.” This so-called second modernist generation was very much interested in understanding modern architecture and housing specifically, not as a universal template that you impose, but as a process that first requires an anthropological and social study of the population you are housing.

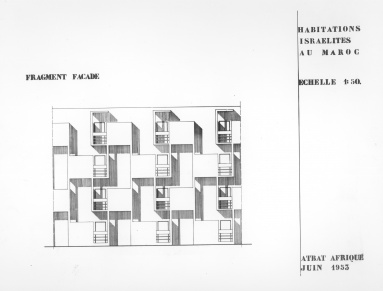

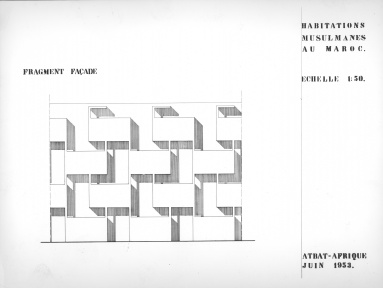

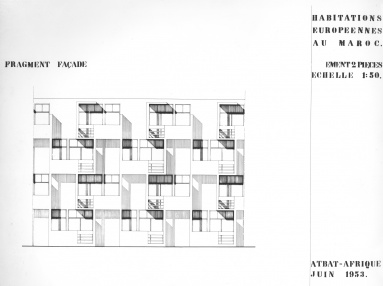

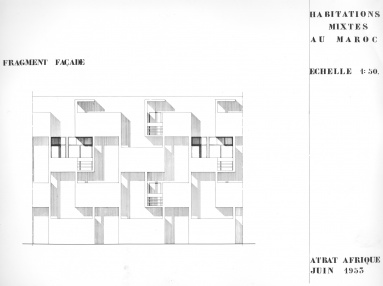

As in the example you provided, these projects sometimes succeeded, but they also failed on many levels. The approach was frequently typological: reimagining what a medieval Islamic city was, taking its courtyard houses and stacking them vertically into a building. In the case of ATBAT-Afrique, the architects proposed variations on this typological formula that tried to address the different socio-religious groups that historically occupied different quarters of an Islamic medieval city.

In one such design, the Muslim population received a walled balcony because they were supposedly more concerned with questions of privacy than their Jewish neighbors, who got a more partial open terrace conditionopen terrace conditionSerhat Karakayali, “Colonialism and the Critique of Modernity” in Colonial Modern, Aesthetics of the Past Rebellions for the Future (London: BlackDog, 2010), 44-47. So you can see how the process could be full of fraudulent assumptions and cultural stereotyping. Much of this design work supposed that social dynamics were frozen in time, when in fact many of those cultural practices were continuously evolving and the communities to be housed were more culturally similar than different.

Drawings of Jewish community housing facade, Muslim housing facade, Christians (European) housing facade and mixed facade.

Model House – Mapping Transcultural Modernisms

The other challenge that you allude to occurs during the process of physically displacing communities. When new communities formed within those modernist structures, typically located on the periphery of urban developments, the socio-religious infrastructure of the old city was totally erased.

The problem here can also be drawn back to the colonial regime and the post-independence nation-state, both of whom characterized the historical city as unhealthy and unhygienic, lacking modern infrastructure and amenities, such as electricity and sewers. The French colonial solution in a North African city was not to demolish the medieval town, but to actually “preserve” it—surrounding it with a modern, gridded city featuring modern infrastructure. This new city contained all of the new public institutions, like schools and health care centers, and had a commercial boulevard lined up with embassies, theaters, etc.

Left: 1950–1953

Photographer unknown / Memoire des Architectes modernes Marocains

Right: 2015

slobodne veze wordpress

This new town competed with and undermined the medieval city on all of those levels, and in many ways undermined its viability. Using colonial tools, the post-colonial state doubled down on this approach, continuing to look at the medieval city as regressive and ignoring its social, environmental, and economic benefits. It instead followed European models, building accepted types of mass housing, such as in Nasr City outside Cairo.

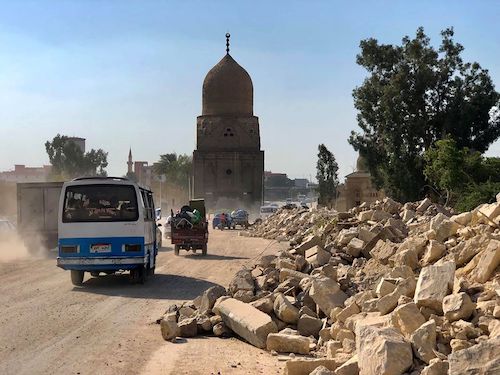

The medieval city was never given a chance to succeed in the modernizing state. Many old cities like Cairo, Beirut, and Istanbul, were crisscrossed with Haussmannian boulevards. While well intentioned and seen as part of a process of modernization, this car-focused approach to the city radically cleared the urban fabric, leaving its mosques, churches, and other communal structures as isolated monuments—detached from the communities they historically served… A recent example, unfolding as we speak, is the clearing of the City of the Dead in Cairo. The modern, twentieth century tombs are being erased (while the historical ones are supposedly being preserved) by the construction of a new highway, ironically called the Paradise Axis Highway!

Photography by Youssof Osama

What do you think is the future of a mosque as a typology? Will it go back to being more of a public space with a variety of architectural programs, or will it be further reinforced as a symbol of power?

First, regarding the very first mosque, although there is of course no visual or physical evidence that stands today, historians have indeed come to the conclusion that the earliest mosque was the house of the Prophet Muhammad. It was a modest courtyard house, with no dome or minarets, or with any other features we identify today as belonging to mosques. The courtyard, where a small Muslim community gathered and prayed, had palm trees that provided shade and its perimeter wall was described as low. So it wasn't even a completely private space.

We know that for the first hundred years there was no mosque architecture that we could recognize as such today. Prayer spaces were created by simply orienting towards Mecca. The direction of such orientation changed during the life of the Prophet, from facing Jerusalem to facing Mecca. This could be perhaps read as a sign of some malleability and evolution in the religious understanding of this space of worship. The early Islamic periods also showed a high degree of permissiveness in the construction of mosques. At that time, mosques were frequently erected on the sites of existing temples and churches, reusing and recycling their materials. A case study here would be the Umayyad mosque in Damascus, which was built out of the remains of the Roman temple and the churches that had previously occupied the site. At a certain point, it also functioned concurrently as a mosque and a church... A mosque, like an Islamic theological text, was emerging from the existing religious landscape and geography of West Asia and North Africa.

Gallica Digital Library

But soon the architecture of the mosque transformed radically. With the emergence of large, powerful dynasties, a mosque started to become recognized more as a typology and its specific features identified: hypostyle halls, iwans, domes, minarets, etc. Indeed, as you describe it, a mosque became a symbol of the Caliph or of the emerging dominance of a new dynasty. As the Islamic empire grew and spread geographically eastward and westward it came into contact with other cultures. Religious architecture was able to absorb, assimilate, and transform aspects of these new building practices, and traditions. Here you can think of the influence of Georgian and Armenian architecture on the 12th century islamic Saltukid funerary architecture as a concrete example.

However, books on the history of Islamic architecture have continuously aimed to define and classify the architecture of a mosque, less in terms of these dialogical traits, and more along the lines of pure typological and dynastic shifts. It is worth mentioning that this history of Islamic architecture was shaped first by the encounters of Orientalist travelers with the East, and then by the Western archeologists, architects, and scholars, who recorded, measured, and documented the mosque. These figures helped to shape the discipline into the form we understand today. Their system of classification, however, which aimed to fix the mosque as a timeless building—strictly belonging to a specific period, in an authentic, unchanging form—is starting to be questioned, especially with the discourse on Orientalism that has emerged in the last few decades.

This is where my interest in the architecture of the mosque comes in. I am interested in looking at its architecture not in terms of a fixed typology, but as a form that was continuously evolving and transforming. The intention is to move away from considering the mosque as a monument and, instead, towards understanding it as a dynamic form that has been repeatedly constructed, reconstructed, and appropriated, used not only as a sacred liturgical space but also as a space for social welfare programs for the community it served. In other words, accepting the hybrid history of the mosque opens a space for its continued evolution today, where contemporary social or environmental concerns—issues long addressed by this building type—could be brought back into the concept of a mosquemosqueZiad Jamaleddine presents an interesting take on the reconversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque in a recent interview, “Hagia Sophia Past and Future.”.

Photography by Iwan Baan

Our work at L.E.FT on the architecture of the mosque started in academia. In 2011, my partner Makram el Kadi and I proposed a studio that investigated the programmatic and architectural capacities of the contemporary mosque—the mosque being a building type that is practically absent from design studios at architecture schools in the US. We taught the studio that year at Yale University and were fortunate to travel with the students, touring Syria and Lebanon to visit and learn from the great historical and modernist mosques in that region. We revisited the studio at Columbia University in 2016, this time looking at the history of the Ottoman mosque in Istanbul.

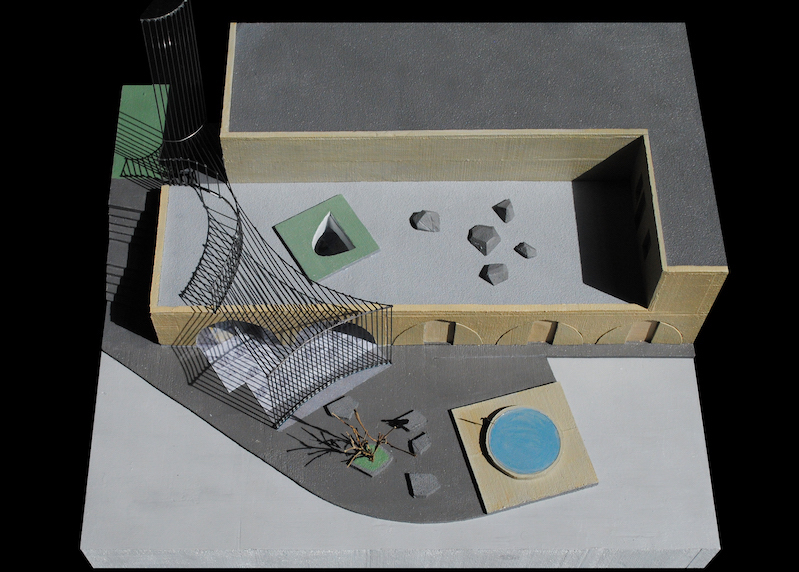

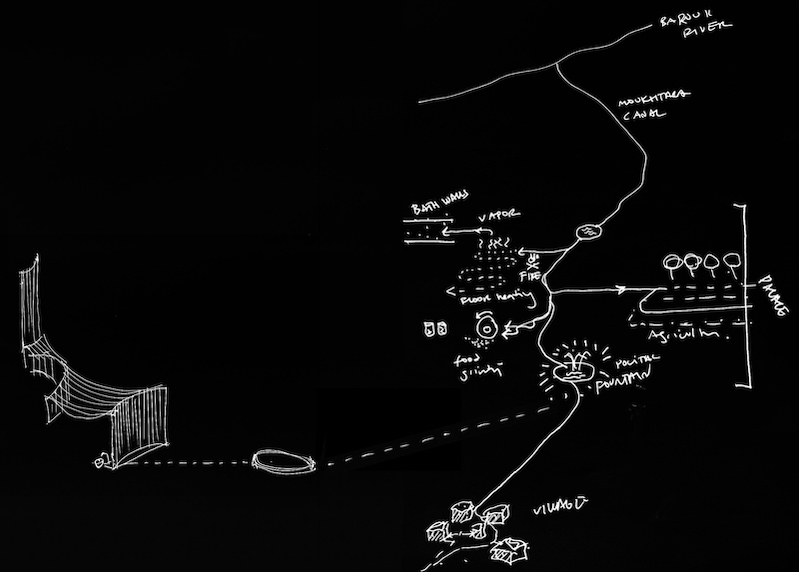

Following the Yale experience, we were commissioned to design a mosque in the rural area of Al Moukhtara in the Shouf Mountains in Lebanon, a region that has had a centuries long history of multiple religious groups co-existing and cohabiting peacefully… Peeling away the modern rhetoric of interreligious conflict that you expect to hear about in the news was one of the main challenges of the design. This commission became an opportunity to push the research and to look closely at the history of the mosque in this specific geographic setting, albeit within the context of a rising regional extremism that held a rigid and deterministic understanding of Islamic history.

So, the question we asked was: how can you build a mosque in a place that is not religiously homogeneous? Could the design offer something to the area’s other religious groups, namely Druze community, and if so, in what form? Mosque design came to represent the aspiration held within this question.

Technically, the design, which was an addition to an existing eighteenth century masonry structure, had to respond to and ground itself in that specific geography. The architectural solution corrected the orientation of the space to Mecca by providing an exoskeleton structure whose concave and convex planar geometry defined a multiplicity of semi-exterior spaces around and on top of the prayer area. The design also erased the parking structure that abutted the site, turning it into a public plaza that extended to the roof via a large stair. As a gesture addressed to all religious communities, the design activated the nearby eighteenth century water fountain and connected it to the new ablution area. Both areas provide fresh, potable water to the whole community, as well as to any visitor driving along the mountain road. In a country where water rationing is the norm, this solution, which takes water gravitationally from a nearby river, demonstrates how one can benefit from tapping into the natural environment without depending on the invasive modern infrastructure. Finally, the thin structural metal of the intervention was reinforced with two words: God (Allah) and Human Being (Insan). The words are pixelated into the architecture, conflating ornament with structure. As a message, they celebrate the humanist, universal, and worldly tradition in Islamic thought.

Today, this architectural inquiry has continued well beyond the practice, conducted again with a scholarly rigor at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) through design studios and history and theory seminars. It has also been pursued through installations and exhibitions at biennials and triennials, including: the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2016, where “The City of Islams” was first exhibited; the Studio X Istanbul in 2017; the Milan Architecture Triennial in 2019; and most recently, the Sharjah Architecture Triennial in 2019. In parallel, L.E.FT has been hired to start working on a new office for religious, contemplative, and spiritual practices at Vassar College, here in the US. Learning from the body of knowledge explored in the research, the building will thrive to serve more than ten religious and non-religious spiritual student groups who will share and negotiate the spaces of the building and its surrounding landscape. Here we continue this vein of research on religiosity and architecture through design investigations.

I feel that the position of our office, sitting at the intersection of research and design work, is a critical potential model for practice today.

Top right: Praygrounds exhibition. Studio-X Istanbul, 2017

Bottom left: Oslo Architecture Triennale, 2016

Bottom right: Sharjah Architecture Triennial, 2019

But the other point I would like to interrogate here is the wording and the language of your question itself, the way you are framing this challenge…

In the essence of all of its elements, “reviving traditional language” is a problematic phrase.

“Reviving” assumes that the condition you are describing is dead and needs to be brought back to life. It assumes that the spatial and architectural practices you are investigating are a thing of the past, divorced from contemporary ways of working—that by reviving them, we are somehow correcting a wrong. To say that something is worth reviving also implies that it once existed in a pure and authentic original condition. As we discussed earlier, when talking about the hybrid evolution of the mosque, this presumption of an “origin” also needs to be challenged.

“Traditional” establishes a condition in opposition to what is understood to be modern. This is a false dichotomy built on a specific understanding of modernity; one that classifies modernity as emanating from Europe. This dichotomy denies Islamic architecture its modernity, resisting any sense of development or evolution into the modern period and insisting on always categorizing it as traditional. This classification is coupled with a timeline that compares the supposed medieval “golden age” of Islamic civilization with its eighteenth century “decline.” Because of this, you very rarely see the study of nineteenth or twentieth century mosques in the field of Islamic architecture. The so-called Islamic city that we briefly discussed earlier falls within this category. Its characteristics manifest through a convoluted, organic morphology, and while it was built in the medieval period it continued to develop and thrive well into the nineteenth century. This form was never recognized by the Western observer as having any virtue, primarily because it lacked “rationality.” This deprived it of an understanding of its own modernity—for example, the environmental benefit in relationship to density—and instead, opened the space to intervene or “modernize” it.

And then, “language” is the third problematic word. Architectural language brings up the question of semiotics: the meaning of specific architectural elements or their roles as signifiers. When it comes to the mosque, for example, the dome and the minaret have become its ultimate signifier today. The mosque’s complex architectural history has been reduced into these two tectonic elements.

“Reviving” assumes demise, “traditional” excludes the modern, and “language” looks at form outside of its social and historical meaning.

So where do we go from there? For me, it’s about recognizing that these spatial practices and architectural typologies have been continuously evolving and that they continue to evolve. They have obviously transformed, influenced by trends from the West and from the East, and are always reinventing themselves. So, if we ever wish to “learn from them,” then the first thing we need to do is to pay attention to this evolution, to try to map it and understand it. And, more importantly, we need to task ourselves to re-write this history and expand the field, insisting on the history of Islamic architecture as truly part of the global history of architecture.

And, as a practicing architect, I would really like to get rid of the self-referential conversation about “language.” Instead, we should strive to produce an architecture that addresses the social, economic, and environmental challenges of our time; that addresses questions of labor, material economies, and natural resources; and that participates in the construction of communities, encouraging a sense of stewardship to our environment and to each other…