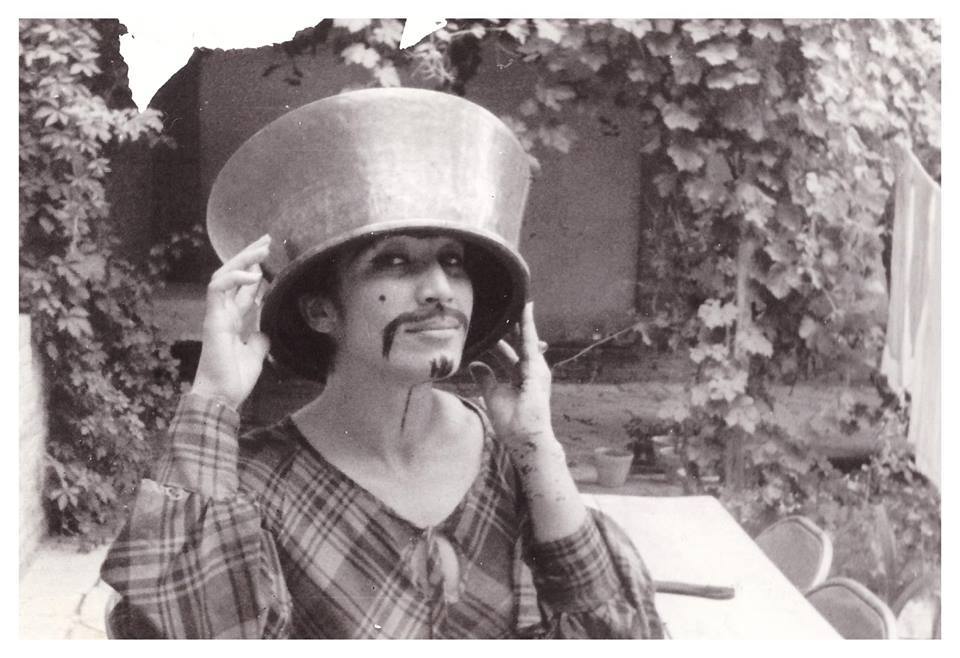

Forugh.Farrokhzad.poet

Forough Farrokhzad was an Iranian poetess and film director whose texts played an important role in the development of contemporary Persian poetry. Challenging the social and artistic conventions of her environment, Forough was always honest—both in her personal life and creative work—defending courageously her right to love and self-expression. Polina Ryzhova writes about the artist's biography, poetry, films, and early death.

“Why should we thank God for having a mother and father?” a strict-looking teacher with a black moustache asks the class. “You, answer me.”

A boy, around seven years old, mumbles in embarrassment:

“I don’t know...I have neither.”

The teacher, without losing an ounce of his theatrical strictness, asks another child:

“Now you. Name a few beautiful things.”

“Moon...sun...flowers...games...” The boy smiles shyly.

“Now you,” the teacher switches to another child, “name a few ugly things”.

“Foot...head…”

The children in class laugh. Many of them have deep wrinkles on their faces and bald patches on their heads. Flies are crawling on their cheeks. The teacher asks one of the students to go up to the blackboard and write down a sentence with the word “house”. The boy, looking more like an elderly man, grabs a piece of chalk in his disobedient hands and, with some difficulty, writes on the board the Farsi words خانه سیاه است (“The house is black”).

This is the final scene of the documentary The House is Black, made in 1962 by the young poetess and director Forough Farrokhzad about the Tebriz leprosorium. During the approximately twenty-minute film, we see bits of an apparently normal life: people eat, pray, learn, get treated, celebrate a wedding. Perhaps only the physical appearance of these people is remarkable: their skin is swollen and lumpy; it looks like they have poorly-made silicone masks for faces. Many are missing noses, fingers, hands: in advanced cases, leprosy often leads to necrosis. The camera does not turn away from disfigurement and does not deliberately look for it in the crowd—the frame captures life as it is, although it is the life of people literally gnawed at by disease. The black and white sequence is accompanied by an admonishing male voice, telling the viewer that leprosy is curable and that the society must help its victims, and by the soft voice of Farrokhzad herself: she reads her poetry about God, life, and death.

The scene with the children is, perhaps, the only live-action fragment in the film—this can be seen in the embarrassment of the responding students and the excited giggles of the class. It was important for Farrokhzad to finish a documentary with an artistic image: despite the fact that children of lepers were often born healthy they were forced to live in the “black house” and it was highly unlikely that they would ever be able to leave it. Farrokhzad herself felt similarly confined for her entire life and she could not ever accept it. It thus seems completely natural that, when she was leaving the leprosorium, as if protesting against this universal unfreedom, she decided to adopt a local child—that very same boy who in the film speaks shyly about games—and, with the consent of his parents, took him with her.

“I can do it too”

Forough was born and grew up in Tehran. Her father was a colonel, her mother a housewife, and she had two sisters and four brothers. The family belonged to the urban middle class—they had a spacious house with a garden in the city center and a home library. The father, although militarily strict, endorsed secular values: he himself taught the children how to read, making no exception for the girls. During that time, the Iranian ruler Reza-shah Pahlavi, indebted to the British military for his power, was pursuing a policy of Westernization. A university was opened in Tehran, roads were paved, European dress was introduced as a replacement for traditional loose robes. In 1935, the year Forough was born, a decree was issued that made removing the veil mandatory. Women were given access to education and could work in government institutions; schools were opening where girls could study together with boys.

Relatives recalled that Forough was a very rebellious child. She liked competing with her brothers and claimed that she was “more of a boy than all of them taken together”.

An episode told by her younger brother Fereydoun is exemplary here. Once he, along with another brother, decided to urinate from the balcony onto the trees below as a joke. Intending to taunt Forough, they teased: “look what we can do, you can’t do it!” Then Forough told themtold themMichael Craig Hillmann. A Lonely Woman: Forough Farrokhzad and Her Poetry. Washington: 1987. P. 7. that she “can do it too,” moved closer to the edge of the balcony and repeated their accomplishment without a moment’s hesitation.

With age, the difference between the position of girls and boys became more obvious for Forough. Her brothers were sent to study in Germany, while she, after grade nine, began learning drawing and sewing in a vocational school for girls. Very soon, the question of marriage came up. Forough decided to take the initiative away from her parents and chose her second cousin Parviz as her fiance: he visited the family often and shared Forough’s interest in literature (writing humorous short plays in his free time). Parents on both sides were against the marriage, as the groom was almost twice as old as the bride. But Farrokhzad insisted—she married Parviz, moved to another city with him, and gave birth to a son.

Improper wife, improper mother

Forough did not take marriage to be the start of quiet family life. Rather, she saw it as an opportunity to run away from the parental home and finally become a free individual. In some sense that was what happened. During that time, Iranian women were obliged to behave with restraint before marriage: any liberty they permitted themselves could launch a wave of rumors capable of scaring away potential suitors. After marriage, on the other hand, women could don brighter, more provocative clothing, wear make-up, interact freely with men—marriage served as a guarantee of their good reputation. But Farrokhzad was too uninhibited even by the standards of a married woman: she could often be seen in a short dress and with a stylish haircut, her lips brightly painted. Sometimes her proper and prim neighbours spotted her looking like that while strolling with a pram, which made them indignant.

Forugh.Farrokhzad.poet

Parviz thought that he could be an authoritative mentor for Forough, introducing her, as her senior, to the adult world—but the young wife clearly had different plans. She travelled from Ahvaz to Tehran by herself (which caused the poetess’ mother to write to her son-in-law, asking him to be stricter with Forough), and struck up numerous acquaintances in literary circles. Soon she began an affair on the side. Farrokhzad did not make a terrible secret out of the affair: the vicissitudes of this amorous relationship were reflected in her explicit poetry, which was published in literary magazines. Her personal life was the subject of public discussion.

After three years of married life, Forough filed for divorce. According to tradition, after divorce the children were to remain in their father’s care. In theory, Farrokhzad could have tried to change the situation, but she did not: she had no complaints about her husband and she herself confessed to being unfaithful. For the rest of her life, Parviz’s family never allowed her to see her own child. Her longing for her son and the feelings of guilt for their parting became a crucial topic of her poetry—this can be seen, for instance, in the poem “The Captive,” which lent its name to her first book.

After her divorce, Farrokhzad attempted to return to the parental home but her father threw her out, claiming she had disgraced the family. The poetess was forced to live for several months with her friend, the writer Tusi Ha’eri. After acquaintances began to spread rumors about their relationship, Khairi asked Farrokhzad’s father to let his daughter return home, and he gave in.

Woman, thus human being

Farrokhzad became the first woman in the history of Persian literature to openly write about love and sexual feelings. Her poetry was challenging even for free-thinking intellectuals: literature was considered a male vocation, and consequently, only men were allowed to narrate their amorous experiences. For instance, the poetry of the young rebellious poet Nosrat Rahmani, who published his works around the same period, was much more brazen, but the reputation of the most scandalous author of the time was granted to Farrokhzad.

It was quite difficult for her to elicit a serious attitude towards herself and her art. Usually, the press called male poets exclusively by their family name, but Farrokhzad, for many years, remained merely “Forough” for everyone. Her colleagues were constantly spreading rumors about being romantically involved with her. Those who indeed were her lovers also did not make a secret out of it. One of her editors even published a short story, vividly describing their relationship; from the details mentioned, the heroine of the story could quite easily be identified as Farrokhzad. In literary circles, she was perceived as first and foremost an attractive young woman—sometimes she managed to take an ironic stance towards this. The writer Houshang Golshiri reminiscedreminiscedQuote from the documentary Forough Farrokhzad: The Green Cold (2002) by director Nasser Saffarian., that during one of the parties he witnessed the following scene: one of the guests was trying to seduce Farrokhzad throughout the entire evening; at one point she got tired of it and she hit the overzealous wooer with a direct question: “Tell me, do you want to sleep with me? Then let’s go to another room. And then sit down like normal people and talk.”

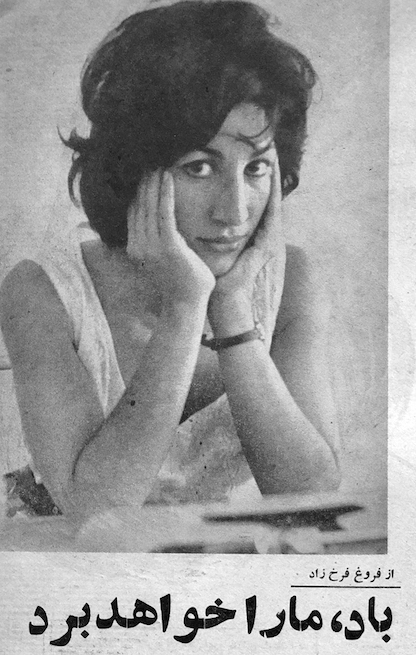

Right: Fragment Forough Farrokhzad's poem “The Wind Will Take Us”

The divorce, parting with her child, and society’s malicious gossip ultimately caused the poetess to have a nervous breakdown: in 1955 she spent a month in a psychiatric clinic, where she underwent electroconvulsive therapy. But this did not change her views, and furthermore, she did not lose hope in communicating her stance to her readers. In the afterword to the second edition of The Captive, Farrokhzad writeswritesMichael Craig Hillmann. A Lonely Woman: Forough Farrokhzad and Her Poetry. Washington: 1987. P. 29.:

“When I leaf through magazines and open volumes of contemporary or classical poetry… I see that men everywhere have described their love and beloved with utter frankness and freedom and have compared the beloved to everything and have voiced imaginatively and poetically all manner of petition to the beloved and they have described all of the stages of love experienced at the beloved’s side. And people have read these books with complete equanimity, no one screaming out in protest that ‘O lord, … the foundations of morality have been shaken, and general modesty and purity are about to collapse and the publication of this book is dragging the morals of the youth to perdition!’”

In 1956, tired of societal pressure, Farrokhzad took a nine-month trip to Europe. She explainedexplainedMichael Craig Hillmann. A Lonely Woman: Forough Farrokhzad and Her Poetry. Washington: 1987. P. 31. her departure from Tehran thus: “I wanted to be a ‘woman,’ that is to say a ‘human being.’ I wanted to say that I too have the right to breathe and to cry out. But others wanted to stifle and silence my screams on my lips and my breath in my lungs.”

The Power of Words

Farrokhzad’s poetry outraged her contemporaries not just by its explicit nature, but also by its principled dissimilarity to classical Persian poetry. For Iranians, poetry has always been the subject of national pride, as its traditions can be traced back through the ages: the first Farsi poetry of Rudaki, laying the foundations of Persian literature, the Shahname of Ferdowsi, the “rubaiyyat” of Omar Khayyam, Rumi’s Mathnawi, Hafez’s “ghazal”, Saadi’s lines about the “children of Adam”, which are woven onto a carpet that hangs on the wall of the UN headquarters in New York. In Iran, classical poetry is not just respected, but genuinely loved—for instance, the collected poems of Hafez is still the most popular book in the country, after the Quran.

In the 1920s, Persian poetry split into traditionalist and modernist: that which reproduces the classics, and that which tries to rethink it. The followers of new poetry, headed by Nima Yooshij, no longer felt like they were courtier poets, frozen in time—they wanted to write about problems and experiences that were relevant to their time. New form followed this new content: there were experiments with measure, rhythm, and the poetic lexicon. At the end of the 1950s, thanks to the poet Ahmad Shamlou, blank verse entered the stage of Persian literature. Modernist poetry also introduced a new lyrical hero: not a wise man who has thoroughly comprehended life, but a wayward, restless individualist.

Obviously, the traditionalists thought that modernist poems have nothing to do with poetry, and that the rejection of traditional forms was tantamount to a rejection of Iranian culture as a whole. The political context in this opposition could also be traced: the traditionalists supported Shah Pahlavi, while the modernists took him to be a usurper and were against his rule. Farrokhzad belonged to the generation of young rebels, but, being a woman, even against their colorful backdrop she still stood out&

Forough as an author was shaped primarily by the influence of Iranian literature, not European. Challenging tradition, she simultaneously was drawn to it, making it into her poetic ally. At the age of twenty three, Farrokhzad became a more mature author: if, in her first poetry collections, The Captive (1955) and The Wall (1956), the lyrical hero of the poems was more concerned with amorous tumults, in her third collection, entitled Rebellion (1958), philosophical contemplation made an appearance and the topic of death was clearly expressed for the first time. The author, in accordance with the title of the collection, no longer felt herself to be merely a misunderstood victim—anger and resistance awakened within her, her voice ringing with all the more assurance. Later Farrokhzad would describedescribeMichael Craig Hillmann. A Lonely Woman: Forough Farrokhzad and Her Poetry. Washington: 1987. P. 35. “rebellion” to be "the hopeless thrashing of arms and legs between two stages of life... the final gasps for breath before a sort of release".

This release took the form of the poems Farrokhzad began writing at the end of the 1950s. They were published in 1964 as part of a collection entitled Another Birth. This collection made an overwhelming impression on critics and readers, turning the talented young woman Forough into the great Iranian poetess Farrokhzad. Simple images from childhood became powerful universal symbols. For instance, in her poem “I pity the garden” (translated from Farsi by Sholeh Wolpé) the abandoned garden is simultaneously a disintegrated family, Iran during Farrokhzad’s time, and—in a broader sense—human life:

No one thinks of the flowers.

No one thinks of the fish.

No one wants to believe the garden is dying,

that its heart has swollen in the heat

of this sun, that its mind drains slowly

of its lush memories.

Our garden is forlorn.

It yawns waiting

for rain from a stray cloud

and our pond sits empty

[...]

Secret lover and a film visionary

At this point, the most important person in Farrokhzad’s life was the film producer Ebrahim Golestan. They met in 1958: Farrokhzad was looking for work and Golestan proposed she become an assistant at his studio. Their work relationship very soon turned romantic. Because the producer was married, they were forced to hide their affair, but it did not work out very well: everyone who was part of the creative circles in Tehran knew of it. Despite this, Golestan never commented on his affair with Farrokhzad. Only several years ago, at the age of ninety four, he claimed in an interview that their feelings were mutual, that his wife knew of the affair, but that he could not leave the family. “Imagine you have four kids, would you not like one because you like others? You can have feelings for them [and] you have feelings for two people,” he said in an interview for The Guardian.

It can’t be said that Farrokhzad was fully content with being someone’s mistress: she constantly faced moral condemnation, accusations, and insults. It is knownknownMichael Craig Hillmann. A Lonely Woman: Forough Farrokhzad and Her Poetry. Washington: 1987. P. 42. that after yet another incident, she attempted suicide, swallowing too many sleeping pills, and was found in the nick of time by a maid.

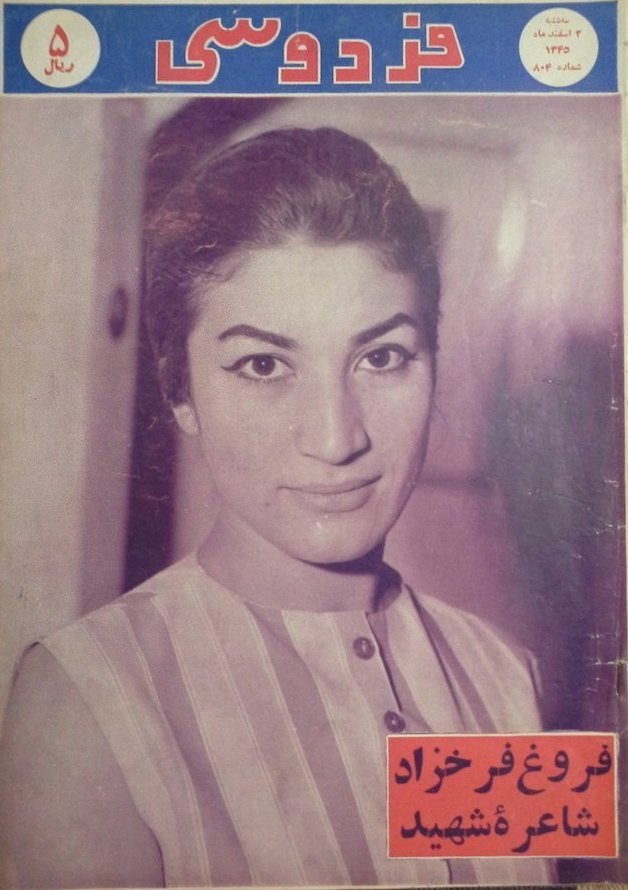

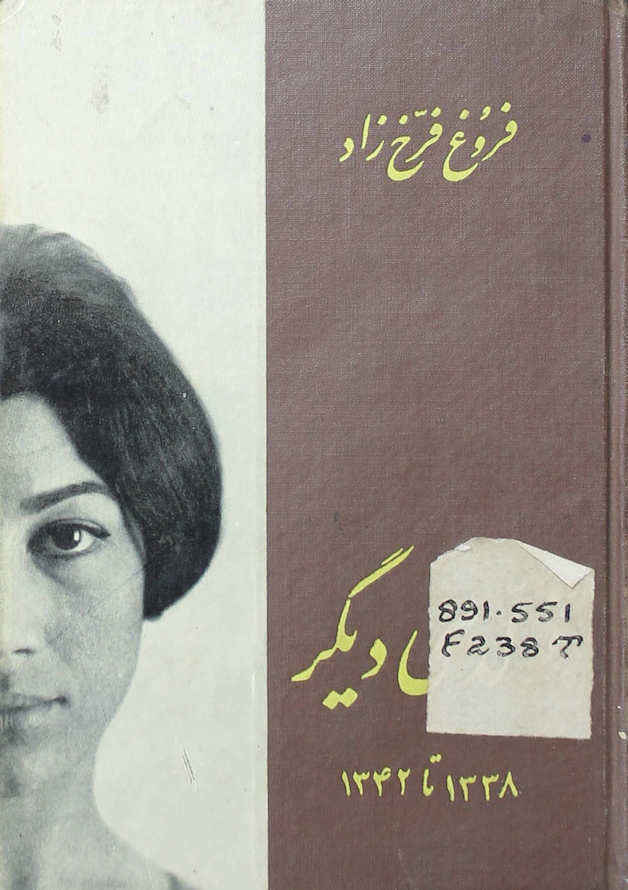

Right: The cover of Forough Farrokhzad's collection of poems Tavalludi-i digar, 1963

Wikimedia Commons

And yet, her relationship with Goelstan allowed the poetess to get into cinema. In 1959, she left for England to study filmmaking. Upon returning to Iran, she began working on the montage of A Fire (1961)—a documentary about a fire that took place at an oil well in Ahvaz and could not be extinguished for a long time. Farrokhzad filmed, cut and montaged, served as producer, and dipped her toes into acting.

In 1962, she went with a crew to Tebriz, where she spent twelve days in a leprosorium. The House Is Black showed the extent of Farrokhzad’s artistic scope: on the one hand, it is a deep social commentary about the problems of people infected with leprosy, and on the other, it is a philosophical statement about life in general, an honest conversation with God. Among the fans of this original debut was Bernardo Bertolucci, back in the days when his career was only just beginning. In 1965, he came to Tehran to interview Farrokhzad. In Farrokhzad’s work, the keen interest in the “small man”, traditional for Italian neorealism, was joined with Eastern multifaceted expressiveness and wit. This very same combination would, after many years, be exemplified in the film language of the Iranian “new wave”—the films of Abbas Kiarostani, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Asghar Farhadi, Jafar Panahi, and other distinguished Iranian directors. Farrokhzad was a visionary.

«You never progressed, yours has been a descent»

Despite her artistic victories, Farrokhzad plunged into a depression—her poetry brought up the topic of solitude with increasing desperation. The boy she adopted in Tebriz, Hossein, had partly helped her cope with longing for her own son, but he lived with Farrokhzad’s mother—it is probable that the poetess could no longer care for the child by herself. When Hossein grew up, he moved to Germany and became a poet—in 2008, a documentary was made about him, named after the very four words he uttered in Farrokhzad’s film—“Moon, Sun, Flower, Game.”

For Farrokhzad, the striving to flee the “black house”, breaking all social conventions, had ultimately turned into a poignant desire to find a real home, and the understanding that this was hardly ever possible anymore. Her poem “Green Delusion”

(translation by Michael Hillmantranslation by Michael HillmanMichael Craig Hilman. Iranian Culture: A Persianist View. Texas: 1990. P. 162.):

Give me refuge, O hearths full of fire - O good luck horseshoes.

And O song of copper pots in the blackened kitchen,

And O somber humming of the sewing machine,

And O day-and-night struggle between carpets and brooms.

Give me refuge, O insatiable loves,

Whose painful desire for immortality

Adorns your bed of conquests

With magical water and drops of fresh blood.

All day, all day,

Forsaken, forsaken like a corpse on water,

I floated towards the most terrifying rocks,

Toward the deepest sea caves.

And the most carnivorous of fish

And the thin vertebrae of my back

twinged with pain at sending death.

I couldn't any longer, I just couldn't.

The sound of my feet arose from the denial of the road,

And my despair had become vaster than my spirit's capacity to endure.

And that spring season and that green-colored delusion

Passing by the window said to my heart:

“Look,

You never progressed,

Yours has been a descent.”

In the last months of her life, Farrokhzad worked on staging Bernard Shaw’s play Saint Joan, dedicated to the life of Joan of Arc, in which she planned to play the leading role. On February 14, 1967, returning from her parental home to the film studio, Farrokhzad was in a car crash: trying to avoid a collision with a bus, she steered her car into a wall. She was thirty two years old.

Farrokhzad’s early and sudden death made her a cult figure. After the Islamic revolution, her poetry was forbidden in Iran for more than ten years, but today the poetess is, according to an author in The Washington Post, “the Iranian equivalent of a rock star”. There are always fresh flowers on Farrokhzad’s grave, and you can see young women in hijab reciting her poetry by heart.

Translated from Russian by Diana Khamis