The Center for Spatial Technologies

The Center for Spatial Technologies (CST) investigates the technological, economic, and political forces that form a city. Researcher Alexandra Mayboroda spoke with the director of CST Maksym Rokmaniko about home space, alternative forms of ownership, and the life cycles of buildings.

I am often asked whether I find it convenient to have my home, my work, and my public events all in the same place. I do.

The Center for Spatial Technologies

In fact, the story of CST began when we won an architecture competition geared towards developing new living standards. We were trying to understand how residential architecture could better correspond to contemporary lifestyles at the level of planning decisions. Later, as part of the Smart Commons project, we analyzed the way public investments lead to a substantial gouging of real estate prices, using High LineHigh LineThe park created on a former New York Central Railroad spur is an iconic example of landscape architecture. Rather than looking at its design solution, we investigated the structure of project financing, the correlation between the cost of real estate and its distance from the High Line (note by Maksym Rokmaniko). as an example, and in our DesignTech research we studied how new instruments change the nature of architecture as a profession.

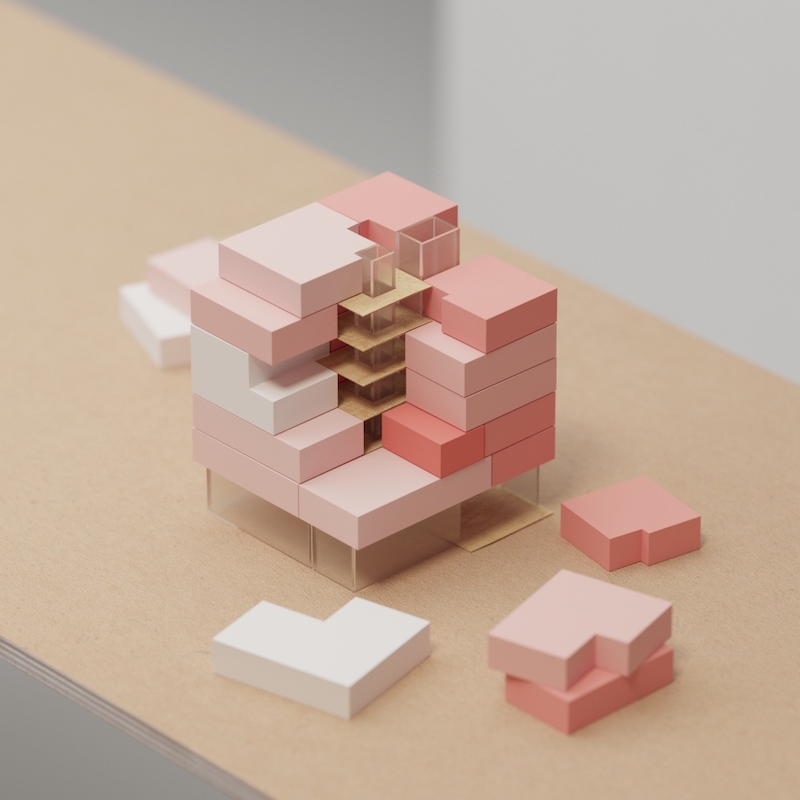

The DOMA project is dedicated to the housing affordability crisis. Instead of looking at buildings and their physical properties, we develop an alternative financial architecture based on joint ownership and distribution of capital.

It is difficult to explain, without concrete examples, what it is we do. I would say that we combine a research approach with experimental design in order to look at important urban problems from a new perspective.

DOMA began with a thought: what if the renter could gradually become a homeowner, acquiring small shares of real estate property for each rental payment? This mechanism is possible thanks to the shared ownership and the alternative financial architecture we are developing.

The Center for Spatial Technologies

in the USA. It is the epicenter of residential financialization. Companies that use artificial intelligence to buy undervalued buildings automatize the management of real estate, inventing intricate forms of credit based on data about users.

The formula is relatively simple: socialism at the level of marketing and focussing on extracting profit at the level of the business model. Based on this research, we have made a video, “Domestic Datascapes,” for the Bi-City Architecture/Urbanism Bienniale in Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

We always look at the “dark side of the Force” in order to keep up with interesting technological solutions. I think it is precisely this aspect of our work that makes us the most severe critics of DOMA. I get the impression that people “from the outside” treat the project with enthusiasm rather than skepticism.

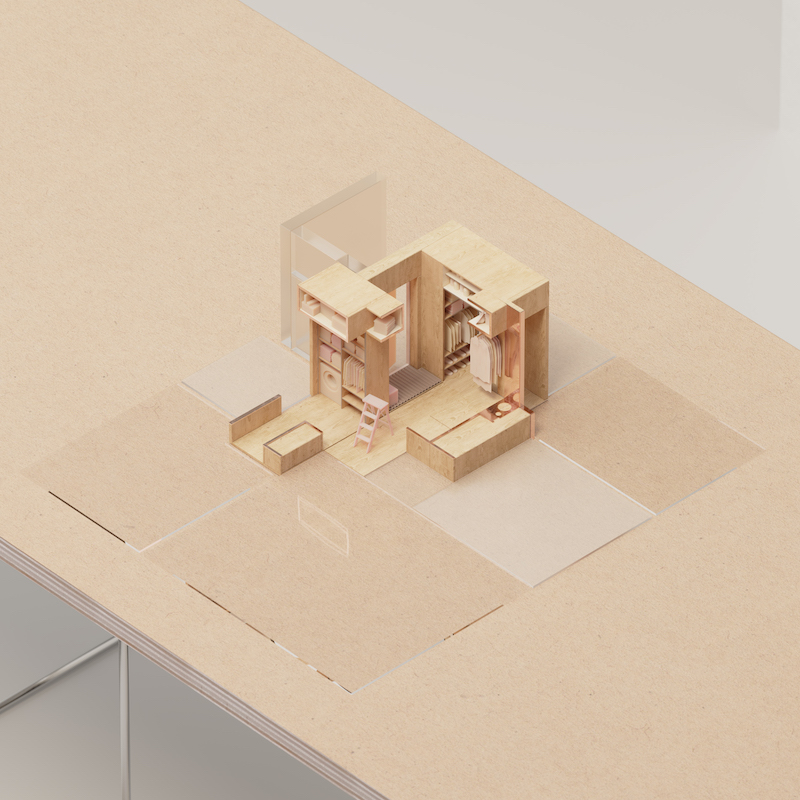

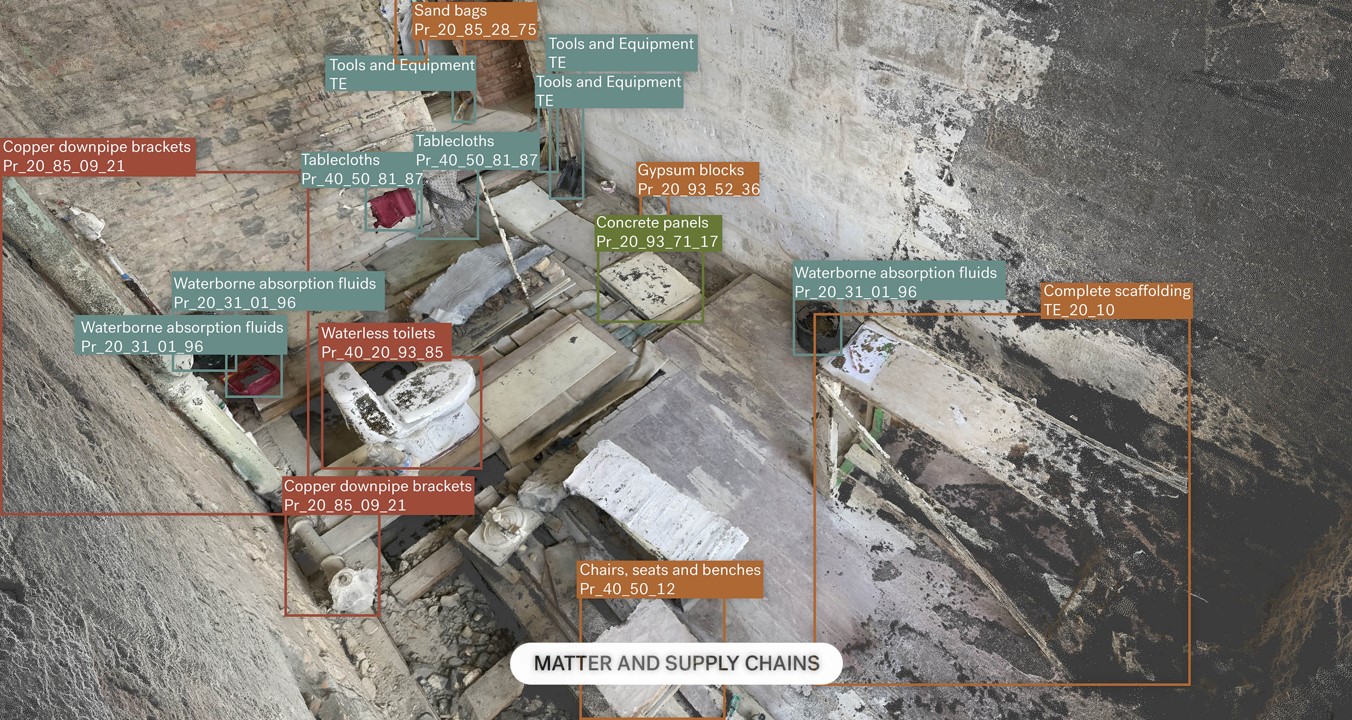

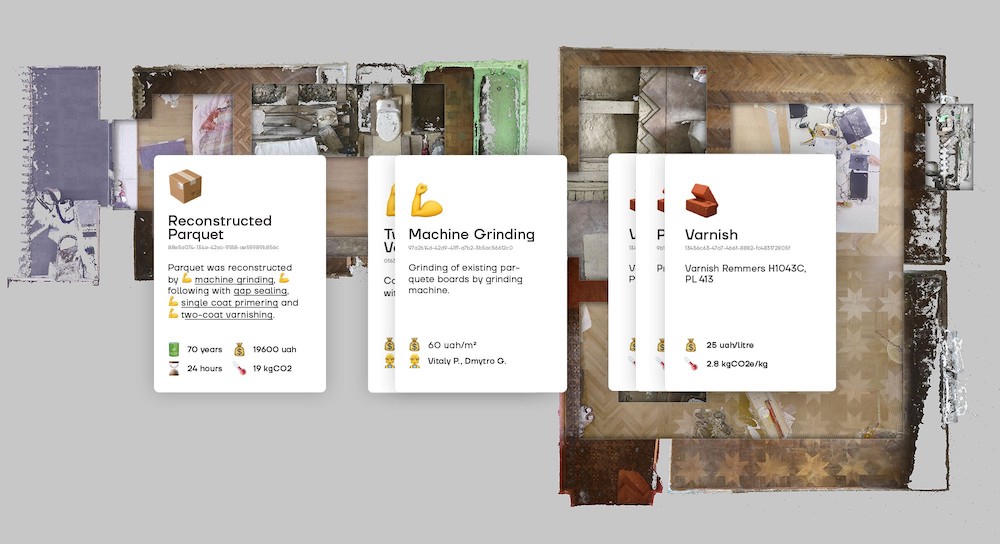

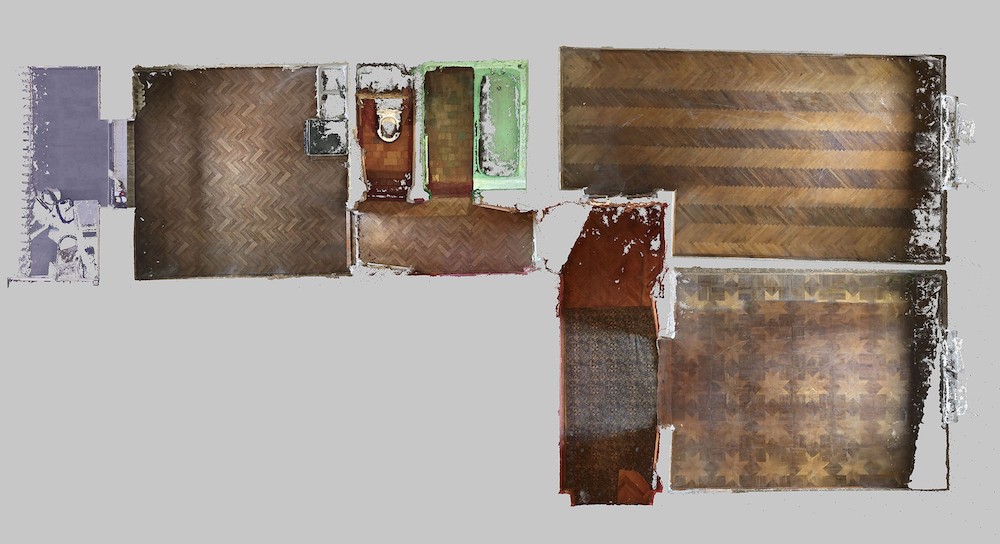

We gathered all the receipts for all the construction material purchased for the renovation and were constantly scanning the space using photogrammetry. In order to gather data about the process, we built a detailed 3D-model of the apartment. We modeled not only the objects in space, but also their various characteristics: who did what work on them, using what instruments, how much did it cost, what materials were used.

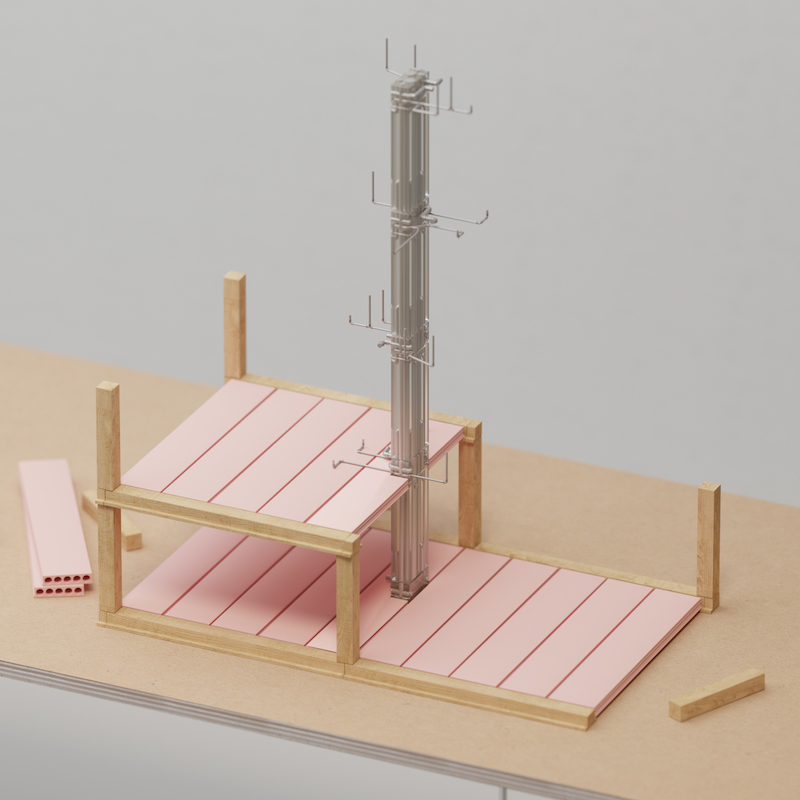

When I showed our preliminary results to colleagues from the London team of Dark Matter Labs, they proposed to make a materials registry prototype together. Ideally, this would let us investigate the trajectories of building materials, their influence on the environment and on local economies. Later on there could be talk of the subjectivity of things as juridical persons. For instance, you buy something the production of which is linked to a large amount of carbon emissions, and the life cycle of this thing you have bought is 100 years. Then you would have to pay a fine if you throw the thing away before the end of its pre-established lifespan.

The Center for Spatial Technologies

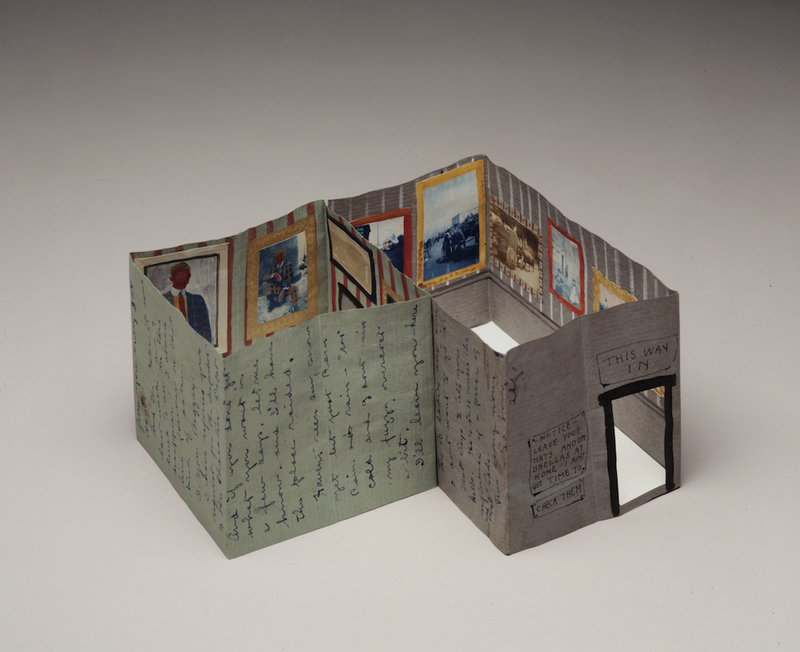

Could it be said that NH turns the material hull of the house from a product we buy at a store, without posing the question of its past and future, into a knot of heterogeneous elements for which we bear collective responsibility?

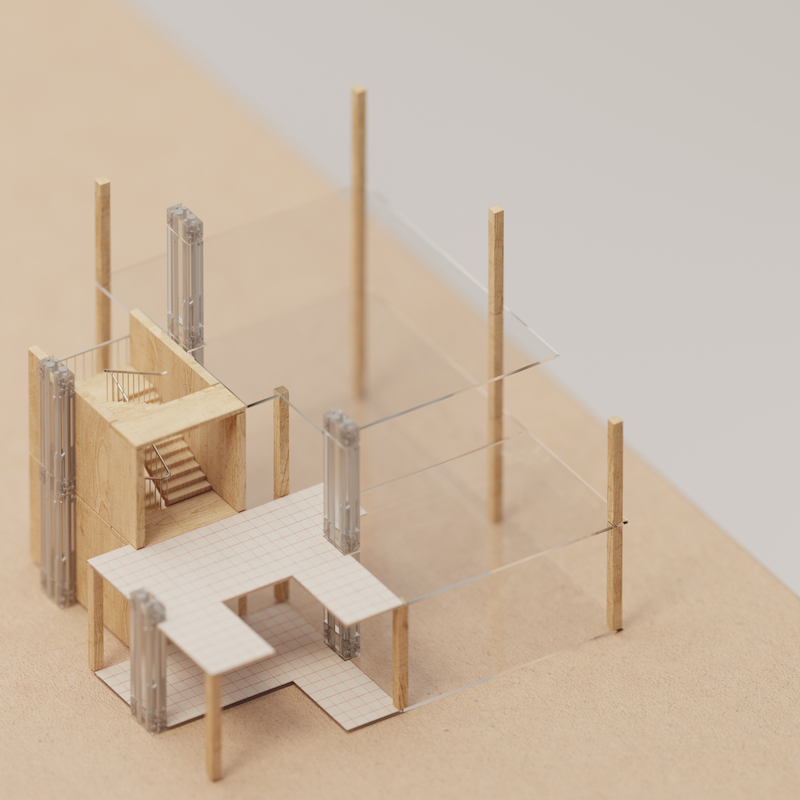

For instance, right now, as part of the Networked Homes framework, we are making a film about a window. At a first glance, this window doesn't do anything, but in its life span, such a window influences a great number of places and people. Its components come from different countries. For example, the plastic profiles are assembled at a factory in Kiev Oblast. They are brought to this factory in truckloads from Germany, cut into six-meter bars. In Germany, they are manufactured from PVC-powder, produced at an oil refinery, and the oil usually comes from Russia. Many people and a lot of equipment are part of these processes. These processes bring profit and have a substantial impact on the environment. This is all regulated by neutral national and international standards.

The window is constantly doing something. It protects from moisture during rain, helps conserve heat in winter and lets air circulate through the room in summer. It lets in solar rays, which warm up the space in the morning and change the population structure of bacteria in the room.

We are used to viewing the window as an extratemporal object, inserted into the order of the universe. We do not raise questions about its history as a technological artifact and the influence that the process of its production has on the environment. Now we look at these questions in detail and thoroughly disentangle such an apparently simple and familiar thing.

. There are elements of the project which we see straight away; we know how to turn them into intelligible research projects, useful for some people and financed by some parties. But in conjunction with that we also just poke around at things, building connections to look beyond the visible boundary of that which is interesting and intelligible right now.

All the projects mentioned by Maxym in this interview were implemented collectively, with major contributions by Mykola Holovko, Anastasia Chaur, Sveta Usychenko, Orest Yaremchuk, Yevgenia Berchul, Olesia Kovalenko, Francesco Sebregondi, Dark Matter Labs team, and others.

Translated from Russian by Diana Khamis