While visiting his relatives in the north of Japan, the artist Ikuru Kuwajima accidentally came across a reference to the German avant-garde architect Bruno Taut, who had visited the area in the 1930s. Intrigued by the story of a European man, born in Königsberg, who happened to be in a remote region of the country that is rarely visited by the tourists even today, Ikuru decided to study Taut's diaries and repeat his route, moving from the shores of the Baltic Sea to the coastline of the Sea of Japan. In this essay, he speaks about the curious coincidences, personal revelations, and disappointments he experienced along this route.

Japan—Prussia

In December 2018, I flew from Moscow to Japan and visited the small northern city of Ōmagari in the Akita Prefecture, in order to see my elderly uncle. This is the birthplace of my mother. During my childhood, I used to come here for holidays to enjoy the green rice fields in the summer and the thick snow in winter and to take a rest from the dense and crowded city near Tokyo where I grew up, where I was constantly experiencing fear and suffering from claustrophobia. Over the past few decades, Ōmagari has become considerably deserted, as if only old people remained there. However, while walking in the city center, I noticed something unusual—a modern four-storey building that stood out against the typical landscape of an uninhabited provincial Japanese city. It was a local history museum, recently built using state funding, in order to rehabilitate the region’s economy. I was taking a tour of the display, which was dedicated mainly to local history and the annual fireworks festival, when I suddenly caught sight of a portrait of a European man. The man in the photo was Bruno Taut—an architect born in 1880 in the Prussian city of Königsberg which later became the Russian city of Kaliningrad. “A native of Kaliningrad in the north of Japan…a native of Königsberg in a rice field...”—I was puzzled, imagining such a strange collage. I visited Kaliningrad in 2017 and the German, according to the text on the label, visited Ōmagari in the early 1930s and was pretty much the only famous foreigner to have praised this obscure northern town. In his diary, he wrote that the vista over the bridge and the distant mountains seen from the same place where the museum now stands was the most beautiful thing he had ever seen in his life. I often experienced the same view when I used to come to visit Ōmagar during my childhood. After such an amazing coincidence, I decided to learn more about Taut. On my return to Tokyo I bought all the books I could find about him and flew back to Russia.

Königsberg—Istanbul

Having read about the life of Bruno Taut, I discovered that this German has played an important role in Japanese culture. In Germany he is known as an avant-garde architect and a representative of expressionism, while in Japan he is famous as a man who uncovered the beauty of its traditional architecture to the world and to the Japanese themselves. Even my seventy-year-old father, not in any way connected to the cultural sector, knew Taut, as he was mentioned in the school books of 1960s as the man who gave descriptions of the Katsura Imperial Villa (Katsura Rikyū) which over the years has become a symbol of the beauty of Japanese architecture. Taut also worked on major construction sites in the USSR and Turkey, but as most of those projects were completed without him he remains largely unknown in Russia. Likewise, almost no one knows Taut in his hometown of Königsberg-Kaliningrad, where the majority of the German and Prussian legacy was destroyed some time ago.

Let me introduce a detailed biography of Taut. He was born in the capital of Eastern Prussia in 1880 and spent more than twenty years there. After graduation, he worked in architecture buros in different German cities. In 1908, he settled in Berlin and started socializing closely with local cultural figures and artists, for example, Herwarth Walden—the founder of a literary magazine and the art gallery “Der Sturm”, which had Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee on display, among others. The influence of the avant-garde artists is already noticeable in Taut’s “Glass Pavilion”, which was constructed for an exhibition of the German Werkbund in Cologne in 1914. This futuristic project was created in collaboration with the fantasy author, experimental poet, and predecessor of German Dadaism Paul Scheerbart. In the early 1920s, Taut constructed expressionist houses in Magdeburg and, upon his return to Berlin, he started working on a large-scale project—the construction of modernist city blocks, which have recently been included on the UNESCO World Heritage List. Following his socialist beliefs, Taut travelled to the USSR in 1932 and took part in the design process for the construction of many important buildings, including the hotel “Moscow”. He left the country a year later due to conflicts with Soviet nomenclature representatives. The Nazis, who had just come to power, started to persecute the architect on his return because of his collaboration with the Soviet Republic. Together with his wife Erika, he managed to flee to Switzerland and from there to Japan via the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Taut was invited there by patrons who wanted to foster Western Modernism in Japan. He first settled in Kyoto and later in a Buddhist temple 100 kilometers to the north of Tokyo. As a foreign architect he attracted the attention of intellectuals and journalists and even delivered a lecture in front of a full auditorium. Despite his popularity, he failed to get large-scale commissions. This can be partially explained by the rise of nationalism across the country as well by the sponsors who misunderstood his expressionist projects. However, thanks to the absence of work, Taut could travel freely and write the texts that later made a profound impact on the history of Japanese architecture. Taut was in love with local culture but left for Turkey in 1936 on receiving a job offer. Taut was supported by Atatürk himself and took part in the construction of important state buildings, including a new university in Ankara. Taut worked so hard on the funeral of the president-reformer that he critically damaged his health, eventually passing away in Istanbul in December 1938. A year later, his widow Erika traveled to Japan to fulfill her husband’s last will: she left his death mask and notes in a Daruma shrine where they had once stayed.

Moscow—Tokyo—Ōmagari

While studying Taut’s legacy from my flat in Moscow, I decided to make something socially useful from his diaries and essays, offering them to a publishing house to be printed in Russian. They liked the idea and this began my work on a future book, even though I was not sure why I got myself into this essentially voluntary project. I lived in Moscow for almost a year, doing research and other work, until I had to travel again to Japan for personal reasons at the end of 2019. This time, thanks to Taut, I had a reason to go to the north of the country for the second time—possibly this was part of the motivation behind my interest in him.

On my arrival to Japan I spent several days in Tokyo and its neighbourhoods, but soon I had a strong desire to escape from the airless, concrete ant hill that I’d run away from fifteen years ago. In his notes, Taut also, on several occasions, mentions his dislike of the capital, noticing the “monstrosities” in the chaos of the city planning, the excess of advertisements, and the impact of “Americanism”. He disdainfully referred to Frank Lloyd Wright’s hotel “Teikoku” as kitsch, despite the fact that the Japanese proudly considered it an important architectural achievement. According to Taut, this unbearable kitsch usually results from a vulgar imitation of Western Culture, an inferiority complex in the face of the West and a naive tendency to trust Western authority. Another aspect that, much to his disappointment, he noticed in the Japanese people was their materialism: it seemed to him that “everywhere people want to sell something”.

I set off towards the north on the “Shinkansen” high-speed train, which has made the journey to Ōmagari considerably shorter so that it now takes only three and half hours. In my childhood, my mother and I used to have to change trains multiple times and the journey could last up to half a day, which in a way had its own charm. Taut traveled even slower, following the route of Matsuo Bashō, a medieval poet and author of the diaries The Narrow Road to the Deep North. I had once wanted to travel that route as well, but changed my mind as Japan had become too touristy. As the train passed the Tochigi Prefecture, 100 kilometers to the north of Tokyo, the landscape transformed. There were less cold concrete houses outside the window, I could see rice fields, mountains, and yellowish red forests. We had been moving north for two hours before the train changed its direction and started heading towards the west of the Sea of Japan. The route ran over a mountain pass, already covered with snow, and then along a wide flatland—so I happened to be in Ōmagari again, from which the sea coast was not too far. The city itself is considered part of the “Ura Nihon”, which is translated as “back Japan”—the economically under-developed nearshore region in the Northwest that Taut admired most.

I got off and as I walked through a deserted train station, I listened to the conversations of passersby, trying to catch the local dialect from which I had always felt a distinctive warmth. However, I did not find it in their speech, as most locals had begun speaking with a boring Tokyo dialect. Back in the day, each Japanese region had its own dialect, similar to the UK, so I often couldn't even understand people in the North. During the last century the government has in fact destroyed local identities and centralised the country, employing compulsory learning of the unified language. This is how the traditional culture of the most ancient people of Ainu, who have lived on the northern islands for centuries, was exterminated, together with the diversity of Japanese culture itself.

My grandfather’s house, which was inherited by my uncle, stands on the outskirts of the city amidst a big rice field. Previously, the rice field was cultivated by the neighbouring families and there were many large cosy wooden houses here, which even if they have survived to today have already lost their authenticity due to numerous renovations. I remember that once the house of my grandfather even had an irori—a traditional fireplace in a square pit with sand and ashes on the floor where fish was sometimes cooked. Taut loved those old houses and wrote that he never encountered ugly farmhouses in Japan. He even dedicated a whole chapter to them in his book Houses and People of Japan, which was published in Japanese and English in 1938. In the book, he compares Japanese farmhouses with European ones, celebrating their cosmopolitanism and admiring, in particular, the variety of forms and materials used for roof construction. Nowadays, when taking a drive to my grandfather’s house, I mostly encounter boring shops with large car parks that one could see on the roadside of any American town.

As a socialist, Taut displayed a special sympathy to the farmers who formed the overwhelming majority of the Japanese population and who, despite living in extreme poverty, remained polite and considerate. Unlike typical foreigners and Japanese nationalists, he did not fetishise and was critical of the privileged caste of samurai, which often exploited the farmers. For ideological reasons, or because of their aesthetic incongruity, Taut did not at all appreciate medieval castles and most of examples of “samurai” architecture, especially the famous Nikkō’s Tōshō-gū shrine built under the will of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in the early 17th century. He referred to it disdainfully as kitsch. At the same time, Taut did not criticise imperial culture which was considered by the Japanese left a remaining legacy of backward feudalism and the origin of class problems in the country. He even praised everything related to imperial culture and recognised, for example, the aesthetic and spiritual affinity of the Japanese farmhouses and Shinto shrine Ise, which was first built more than fifteen centuries ago. Perhaps these contradictions and simplifications were the result of his relatively short stay in Japan. Nevertheless, his viewpoint fascinated local patriots and was potentially one of the reasons that they so willingly accepted this avant-garde architect-socialist who opposed the Nazis.

In addition to houses and landscapes, Taut was also interested in the domestic life of the Japanese people. During his trip around the Akita Prefecture, he wrote, for example, that “Men here dress like Russians while the women look Siberian”. He was bemused by the bamboo stick battles and processions with phallic symbols. I myself did not know about the existence of these exotics practices on the territory of my predecessors, even though it turns out these festivals still take place not far from my grandfather’s house. Taut also described kamakura—little houses made of snow that are usually built in winter in the north during the Shinto holidays. After the publication of the architect’s notes, Japanese from across the country started to travel to Akita Prefecture with the intention of seeing those houses. Basically, Taut was one of the few intellectuals who paid attention to this remote region. Perhaps precisely because of this unusual sympathy, Akira Kurosawa, whose father was born in the village near Ōmagari, wanted to bring Taut’s life to the screen. A German at the Daruma Temple could have become the debut of the world-famous director, but the film production was stopped due to the war.

The Sea of Japan—The Baltic Sea

After visiting Ōmagari, I decided to travel to the capital of the same name in Akita Prefecture, situated on the shore of the Sea of Japan. My grandmother on my father’s side was born and brought up there, however, I have only passed through it. Taut loved this place greatly, and used to call it “ Northern Kyoto”, much to my surprise; as far as I remember, no one spoke so well of Akita. In this capital with a population of 300,000 people there is still not a single hostel, despite the famous architect’s good reviews and the growing number of foreign tourists travelling across Japan. Something was definitely wrong here. I decided to look at this “Northern Kyoto” with my own eyes.

Upon my arrival to the city, I was met by a local architecture specialist who agreed to give me a guided tour of the old city center, which once impressed Taut with its magnificent wooden houses. I set forth with her in hopes of witnessing that beauty, but was immediately disappointed as the region that Taut was writing about has only a couple of houses left from that period. Moreover, the facade of one of them was covered with a huge poster from a real-estate agency—”Northern Kyoto” evidently no longer existed. I had an idea that it was possibly destroyed during the bombardment and I almost began to blame America, when my guide rushed to explain that actually the city had safely survived the war and the unique wooden houses were demolished recently during the economic rise of the 1960s. “They wanted Daiei…”—she said sadly, naming a brand of an outlet chain that became widespread across the country during the twenty years of post-war economic growth.“People here love new things, shopping centers, McDonald’s, Starbucks. Everything that also exists in Tokyo”. The realisation of this cultural suicide shattered me. The northern pearl was destroyed not by poverty, war, earthquake or tsunami, but by the market and post-war centralization of the country. Ironically, this cursed shopping mall was recently demolished because of the decline of the regional economy. Now, all that is left here is a deserted car park.

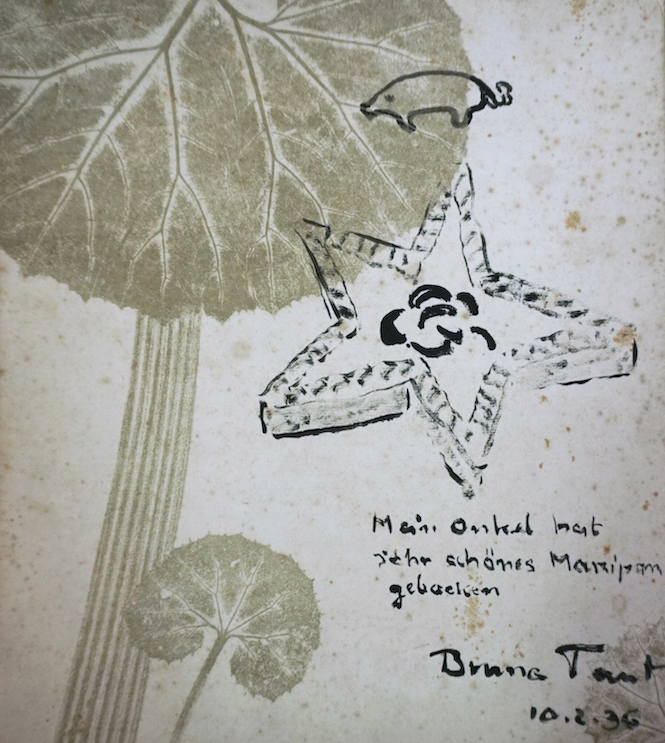

Baukunstarchiv, Akademie der KünsteRight: Ikuru Kuwajima. Bruno Taut’s painting, presented as a gift to the general manager of Kaoru-do confectionery factory in Akita in 1936, November 2019

We visited a few more places related to Taut, including the old house on the outskirts of the city where he stayed for one night. It later turned out that the owner of the house, who had once hosted the architect, was a close friend of my great-grandfather—so, I eventually found a personal connection with Taut, even if it is a very remote one. However, the most valuable catch awaited me in the office of a local traditional confectionery. Taut wrote in his diary that during his time in Akita he visited a confectionery works and tried the local delights. As a token of appreciation, he drew a pig, a symbol of good luck in Germany, on some thick paper packaging, put a marzipan inside (Königsberg’s culinary pride at that time), and gifted it to the owner of the factory, along with the recipe. To my surprise, this factory Kaoru-do still exists and the drawing was kept by the current director, who showed it to me with great pleasure. Actually, wherever Taut went he was always a shameless promoter of Prussian culture. For example, when he took part in the celebration of the traditional summer festival Tanabat during which it is common to attach notes with wishes to bamboo sticks, the architect wrote quotations from works by Immanuel Kant and distributed them amongst local residents. Taut probably missed his motherland and was unconsciously looking for its traces, even in the north of Japan. In his travel diary he wrote: “Pine trees, sand, water—as if of the Baltic Sea.”

I set forth for the nearest coast and Taut’s words proved correct: indeed, there were pine trees, sand, and the sea, which indeed reminded me of the Baltic Sea with its dull sky, cold wind, and desolate territory. The coasts of these remote seas remained uchanged—unlike the Königsberg, which had been totally destroyed after the war, and “Northern Kyoto”, which, unnoticed, had been wiped away by post-war capitalism and the centralisation of Japan.

Translated from Russian by Alisa Oleva