In his four part series for EastEast, the artist and filmmaker Rouzbeh Akhbari is posting brief dispatches from his three-month research trip in Oman. Akhbari’s interest in the region stems from his work on two related projects: research focused on how the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC) translates into local contexts near Iran’s maritime and terrestrial border zones, and an experimental documentary titled Point Rendezvou that follows the informal livestock trade between the Caspian and Persian Gulf littorals.

Dispatch 3: February-March 2024:

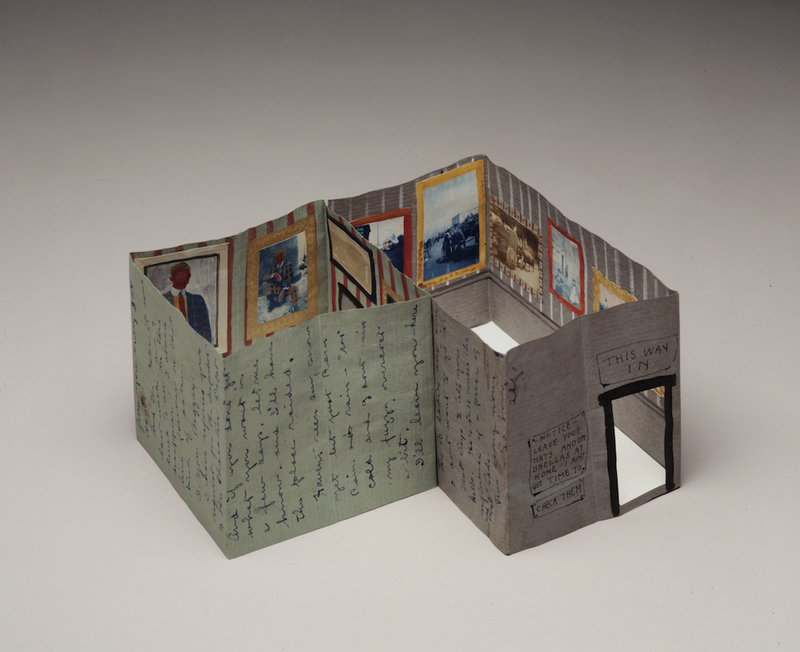

In the months following the Sultan’s brief stay in Khasab, I frequently visited various sites of social reproduction near the city’s port. During this period, I had the privilege of engaging in numerous insightful conversations with individuals whose lives are directly or indirectly intertwined with the informal trade networks that connect Iran’s sanctioned economy to the outside world. Some of them have resided in Khasab for decades, while others were newcomers or transient visitors. These conversations, enriched with personal anecdotes, along with my own observations, provided me with a deeper understanding of the city’s urban history, which is often absent from official accounts of development. Through these narratives, I realized that the story of development in Musandam is nonlinear. The trajectory of “progress” here involves a delicate balance between mobility and blockades. In the following passages, I will recount portions of these oral histories and discuss the curious timing of certain ostensibly unforeseeable events that led to rapid policy changes and architectural modifications in the port.

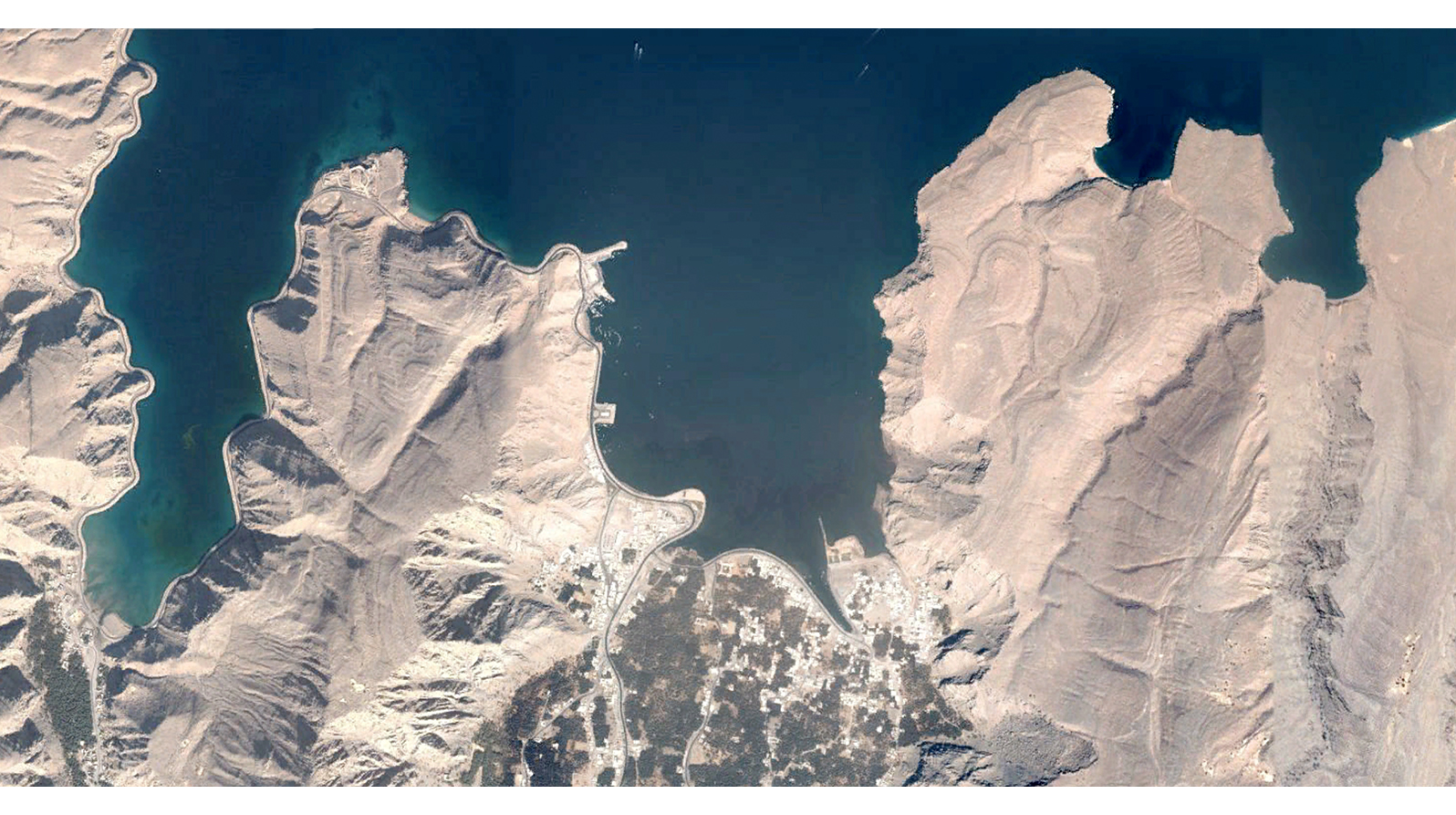

Khasab and its ancient surrounding villages, such as Kumzar and Bukha, have played a pivotal role in maritime trade for centuries. Their strategic location at the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz, coupled with privileged access to fresh water and nutritional sources in an otherwise arid and water-scarce region, has been instrumental in their thriving. The inhabitants of these areas have prospered through extensive interactions with both local and non-local actors. Historically, the sea-oriented morphology of these towns, where nearly every household had direct access to the sea, underscored the importance of a decentralized model of maritime trade in every aspect of urban life. A significant portion of this trade has consistently been with Musandam’s more prosperous and populous northern neighbor: Iran.

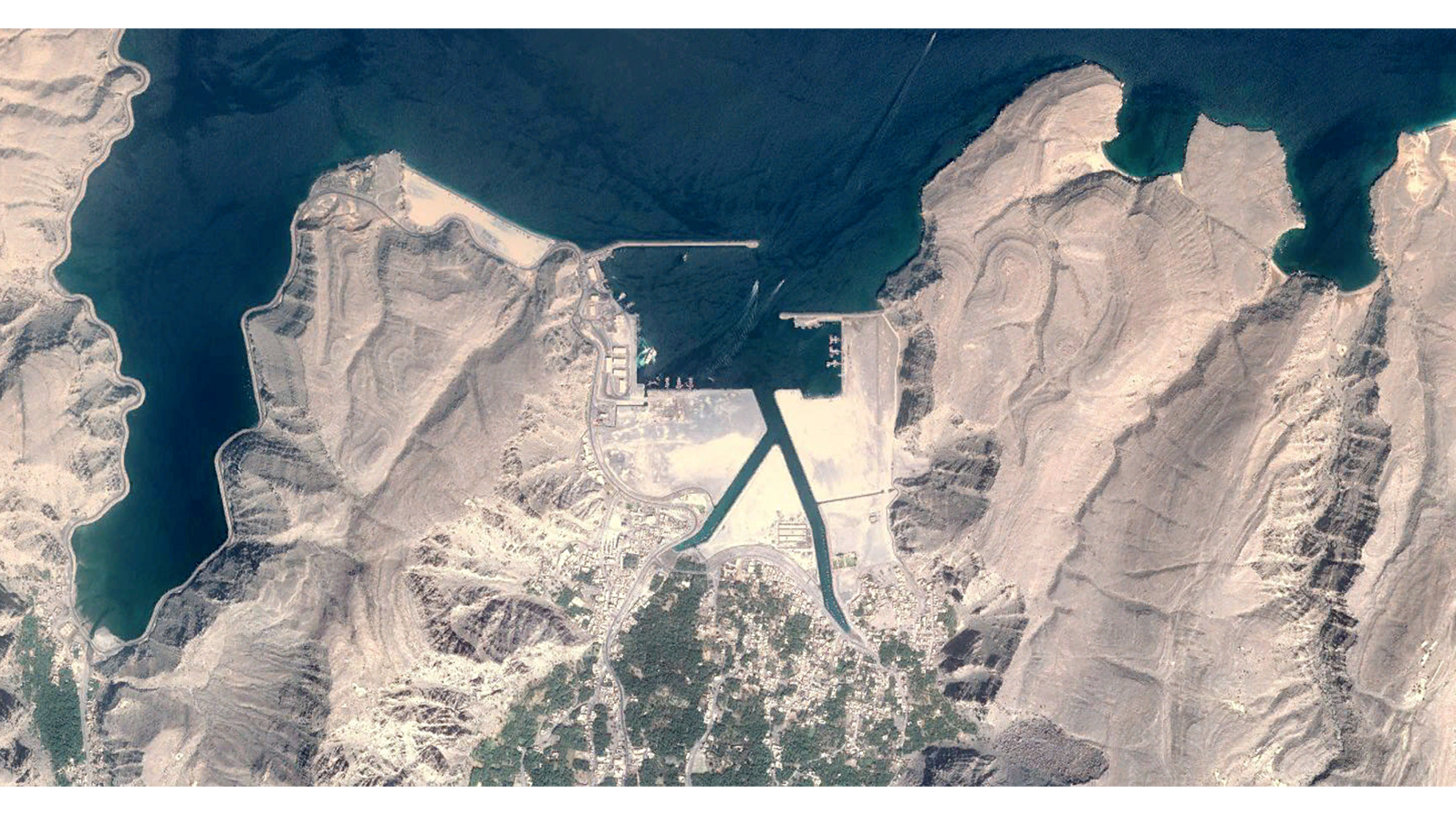

In the past two decades, however, Khasab has undergone massive transformations that have radically re-structured its historically decentralized (one could argue, “free”) trade arrangements. In 2009, a large-scale modern port was constructed at the mouth of the city. As some of the veteran merchants of the city told me, one of the undisclosed objectives of establishing this port was to formalize the long-standing informal trade relations that have come to define Khasab. The soil accumulated through the dredging of the deep-water port was also used to expand the city’s shoreline well over two kilometers into the Strait to establish a free economic zone. With this development, not a single household was able to maintain their direct access to the sea, ensuring that every passage was now subject to the security gaze of the port’s centralized authority.

The stories I heard from both Iranian and local seafarers indicate that prior to the construction of the port, and even in the first few years after its inauguration, merchants arriving on international vessels were allowed to enter the city without the need for visas or passport control. This facilitated free trade, making Khasab an incredibly cosmopolitan and lively site of cultural and financial exchange. During this period, the economic heart of Khasab was an ancient marketplace known as the Iranian souqsouqThe name for a street market, particularly in Arabic- and Somali-speaking countries.. Over time, however, the operationalization of the port coincided with stricter border regimes, ultimately leading to the downfall of the vibrant Iranian souq. This large open-air market, once home to some of the most prosperous money changers, livestock traders, and other transnational enterprises, has now become desolate. The formerly bustling import-export businesses seem to have halted their activities overnight, leaving their office furniture abandoned and the market in a state of decay.

I inquired with my interlocutors regarding the story of the demise of the Iranian souq. While everyone agreed that this wretched fate had to do with the state’s trade formalization schemes, their stories differed in terms of which historical event drove the final nail into the coffin of this once thriving marketplace. Most people who worked at the souq before its disintegration recalled the money-laundering and drug-related accusations leveled against merchants between 2015 and 2017, followed by police raids, as the pivotal moment leading to the market's closure. Some blamed the strict mobility regimes of the port and new border practices that no longer allowed Iranian sailors to enter the city for short-term business stays. Others pointed to lingering COVID-related measures that restricted the arrival of international watercraft to the hours between sunrise and sunset.

Perhaps the most interesting story I heard was related to the gendered roots of the market’s collapse. Supposedly, in 2018, the border regimes were amended to disallow Iranian sailors and merchants from entering Khasab after local women organized a protest in front of the governor’s office. They voiced their dissatisfaction with the predatory behavior of the Iranian visitors and their own husbands, who, buoyed by the fortunes from trade with the Iranians, were engaging in gambling and purchasing unsanctioned services from visitors from the neighboring UAE.

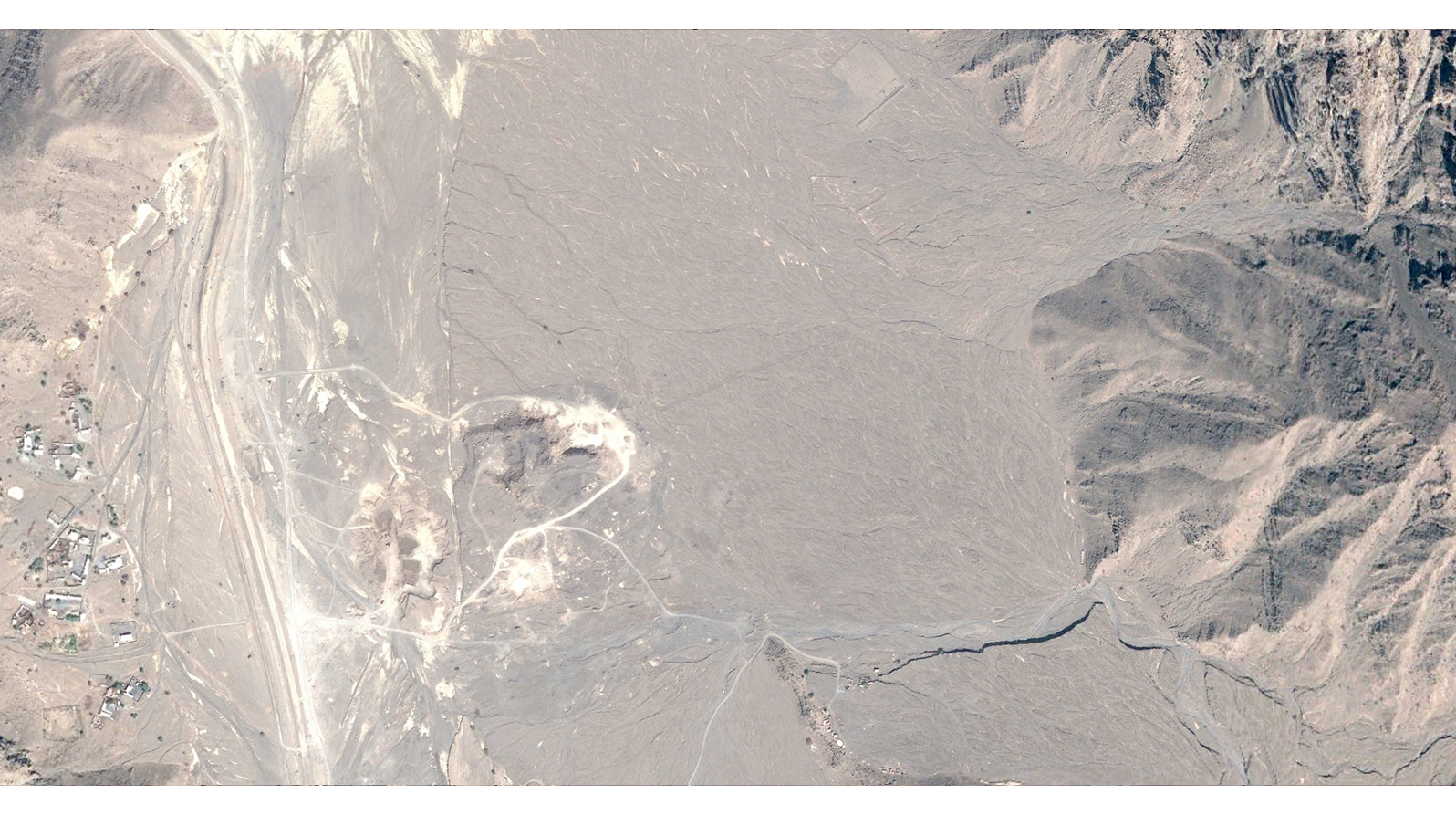

Regardless of the “true” cause of the Iranian souq’s downfall, it is clear that a campaign of criminalizing informal trade and border transgression followed the completion of the port infrastructures. Perhaps the most iconic indicator of these shifts can be seen from outer space: the construction of a massive penitentiary and police training complex concurrent with the operationalization of the port.

Every narrative that I encountered revolved around singular or sequential incidents (in contrast to, say, intentional planning or top-down development models) as the justification for the deposition of the Iranian souq and its ancillary networks of exchange. That is why, when the storage depots in a segment of the port that is frequently used by maritime smugglers burned to the ground without any urgent response by the local firefighter in the early hours of a February morning, I knew this event would automatically have history-making effects. It felt somewhat uncanny that in a matter of days after this costly fire, the port closed down to all incoming traffic by the local authorities under the suspicion that a sheep that was smuggled from Iran was filled with opiods. These two seemingly interconnected events swiftly changed the architecture of the port. Massive cranes were mobilized to install “state of the art” X-ray machines in the port’s customs area, and construction workers were hurried to the northern perimeter of the jetty to build a 5-meter-tall wall where the only gap between fortified fences previously allowed locals to walk near the waterfront and directly gaze into the inner workings of the port.

In my next and final dispatch, I will delve deeper into the material manifestations of the rapidly formalizing (though still largely informal) trade in livestock in Musandam. For now, allow me to conclude this post with a brief note from my conversations with Khasab’s harbormaster following the sealing of the last vantage points into the port.

During our discussion, the harbormaster reflected on the profound changes that had taken place. He spoke with a mix of nostalgia and resignation about the old ways of trade that once defined Khasab’s economic and cultural landscape. He acknowledged the necessity of modernization and increased security but lamented the loss of the vibrant, open market atmosphere that had been replaced by high walls and advanced surveillance technologies. His insights highlighted the tension between progress and preservation, illustrating the complex dynamics at play in Khasab's evolving relationship with its maritime traditions and economic practices.

[Male| 45-50 | Omani (Muscat)]

— Graduate degree and work experience from the Port of Rotterdam

— Rejects my request to enter the port, explaining that the harbor is becoming increasingly closed to the public.

— “Had you arrived three years earlier” he says, “I could have given you permission to walk right in.”

— Explains that the port has recently been purchased under a long-term concession by a Chinese corporation (Hong Kong-based Hutchison port holdings). The company is attempting to acquire an international safety standard certificate—thus the sealing of all gaps in the perimeters and the installation of new X-ray machines.

— Suggests two solutions in order to gain entry to the port:

1. Email the Hutchison ports corporate headquarters and ask for a permit.

2. Get a ticket on the tourist cruise ship that departs from Dubai and has Khasab as a port of call on route to Muscat.

All images provided by Rouzbeh Akhbari