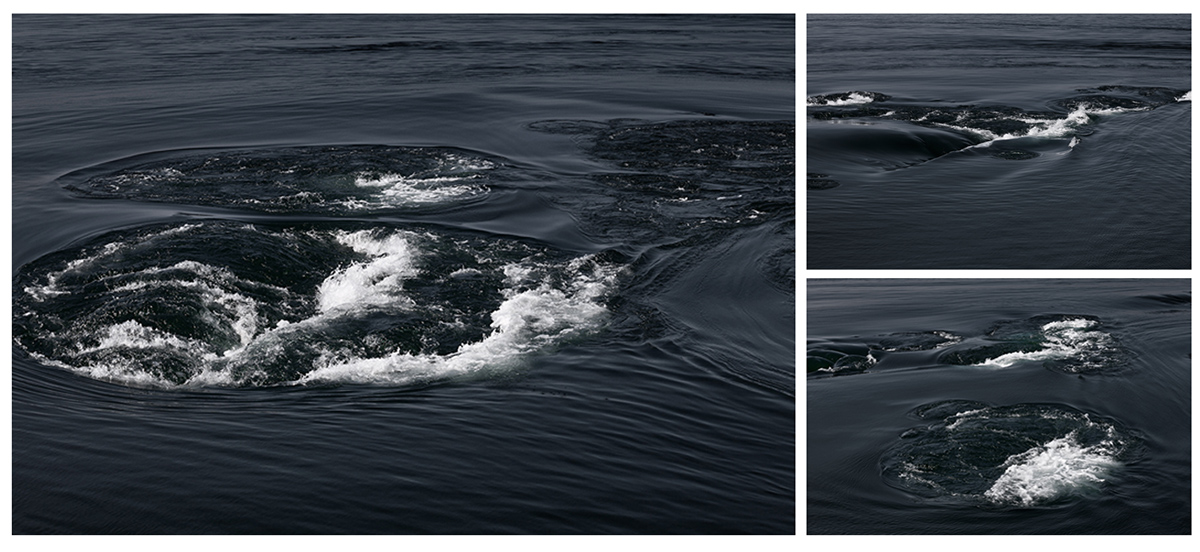

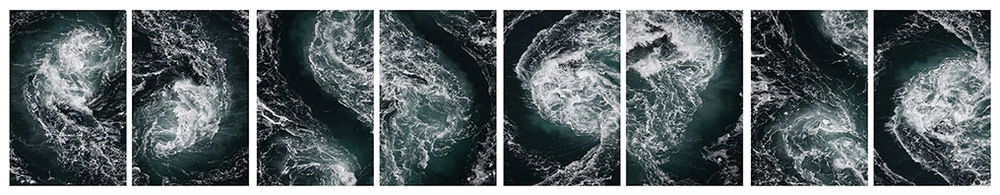

MMV-III / Holes is part of Into the Maelstrom series (2011–2013) by Zoé T. Vizcaíno

Curators and researchers You Mi and Nikolay Smirnov compare two diverse philosophical traditions—the Chinese ideology of Tianxia and Eurasianism, developed by Russian émigrés. Jumping across geographies and times, they discover some unmanifest parallels. This is the second publication from the series Tacit Knowledges—an educational program developed by CCA that looks at different ways of understanding and engaging with philosophy. Through a series of conversations, the project brings to light non-Western episodes of philosophical history as well as gives voice to epistemologies that have been dismissed as irrational or non-systematic.

Russian Slavophiles discovered this path before Eurasianism. In the first half of the mid 19th century they had already formulated quite original interpretations of non-Western philosophy. I especially want to mention Alexei Homyakov’s concept of sobornost’. In general, sobornost’ is an analogue of the term Catholicity—the idea of the universality of the Catholic Church. But Homyakov split this term and claimed that Catholicity is a repressive notion and it is proper for the Western world, to the Catholic Church. Russia, as a center of Orthodox world, according to him, has sobornost’—an ideal of non-repressive and not formal cooperation between people—which is neither equal to Protestant individualism, nor to Catholicist unity. For Homyakov, Catholicity was a “wrong,” i.e. a repressive and formal unity of believers held by the Catholic Church, and sobornost’ was a “proper,” non-repressive unity that provided not formally but according to the religious “spirit” of the Orthodox Church—a “true” unity. One could say it was the first example of such a dual splitting: one part is good, while another one is bad. One is ours and the other one is foreign.

Later, at the beginning of the 20th century, Eurasianists repeated this operation. In general, Eurasianism was formulated after the October revolution, when certain intellectuals and scientists ended up in exile. They tried to reflect on what had happened with the country and tried to formulate the philosophy of “Russia-Eurasia,” a specific “geographic personality,” which is not equal to the East and which is not equal to the West. They did not consider Russian-Eurasian religiosity to be institutionalized clericalism. On the contrary, they thought of the rites and mundane lives of people as interconnected. They assumed that Russian-Eurasian people did not need institutional hierarchy because their life was full of mundane religiosity or, as they called it, “everyday confessionalism.” They said that people who lived in this Russia-Eurasia geographical entity did not distinguish between the ideal and the profane. So these two realms permeate each other, and people try to implement the ideal in every minute, in every gesture of their existence. In connection with this, they also spoke about the orthodoxy of folk, which they contrasted to the orthodoxy of the elite. According to them, the religion of everyday people or folk is different from the religiosity of the ruling classes.

The ideal and the profane permeate each other, and people try to implement the ideal in every minute, in every gesture of their existence

Another concept, developed by these philosophers, is the so-called “Turanian psychological type.” They dreamed about Turan, which is a strip of the land between South and East Asia and North Asia, somewhere in the steppes. Turanians’ consciousness is very concrete and not abstract. Turanians and Russian-Eurasians as successors of the Turanian psychological type just borrow abstract concepts, change, and then implement or realize this modified concept in everyday life. And this is, in short, what the Turanian psychological type, according to Nikolai Trubetzkoy, was.

In general, one could speak of the ideocracy—the rule of idea in all spheres of life regardless of whether it is science, art, ideology, or state structures. In fact, Eurasianists talked a lot about different features of Russia-Eurasia, but I just gave the highlights in order to show how they formulated this theory of specific geographical identity. Moreover, they understood the world as very diverse, having a rainbow-like structure in the geocultural sense. So Eurasianism was the ideology championing cultural relativism. In the beginning, Eurasinists criticized the cultural hegemony of the West and later they began to define the specificity of Russian-Eurasian geoculture as one of many others in this global palette. And they marked all these points that I’ve already mentioned: everyday confessionalism, Turanian psychological type, etс. The classical Eurasianism was formulated around the 1920s–early 1930s.

Later, this group of intellectuals split into a left-wing faction and right-wing one. The left wing was more concerned with socialism; they tried to make a mixture between Karl Marx and Nikolai Fyodorov, while the right wing maintained the classical, orthodox version of Eurasianism. But in general, they all agreed on the idea of geocultural diversity. Maybe the main idea of all currents of Eurasianism was that the world should be unified and diverse.

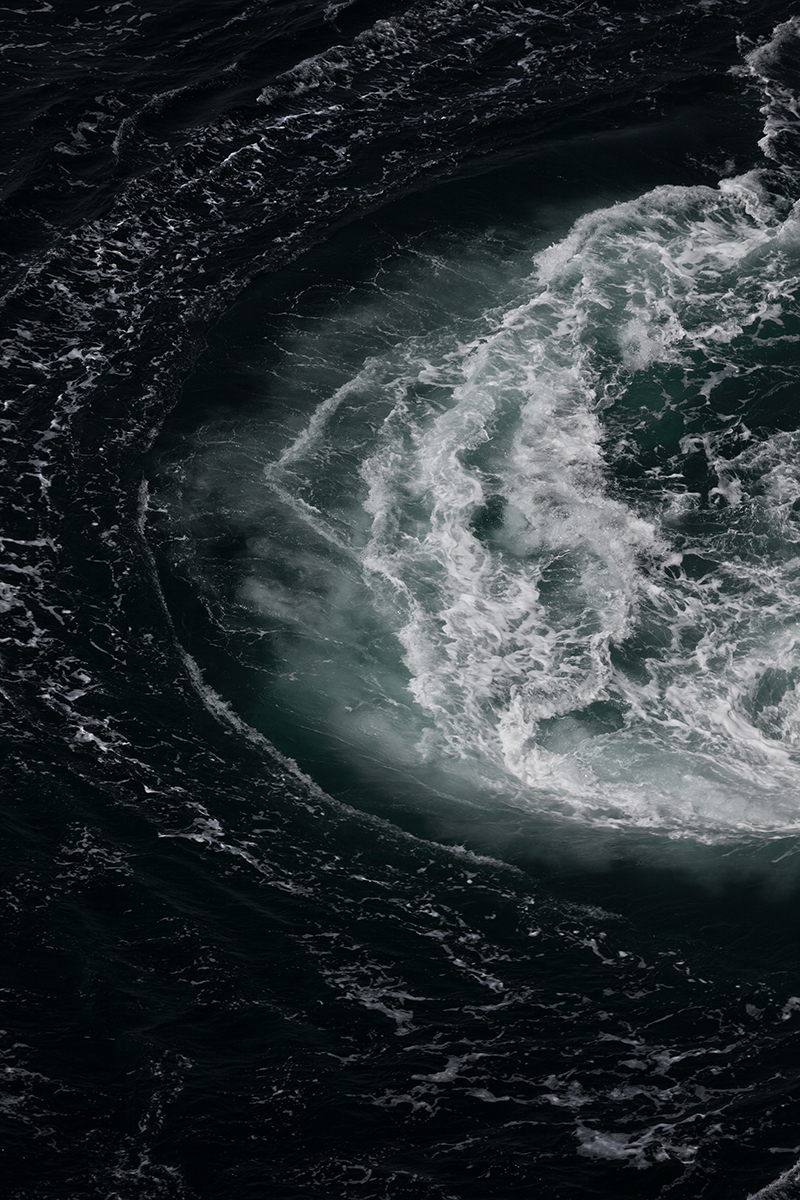

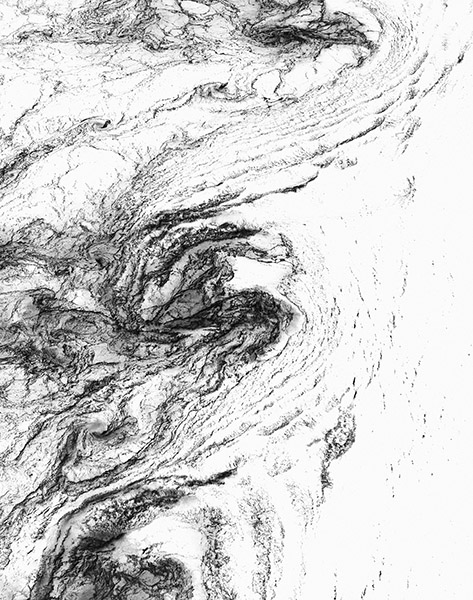

MMV-IV / Storm is part of Into the Maelstrom series (2011–2013) by Zoé T. Vizcaíno

Tianxia literally means “everything under heaven.” It is an ideological system that depicts a hierarchical world system where the Chinese Empire stays at the center and controls or manages everything under heaven with the heavenly mandate. In terms of foreign policy, for the centuries that predated the modern era, it meant that countries on the periphery of the Chinese empire had to enter into a tributary relationship with China. I will return to this question of tributary relations a little bit later, as I have recently been quite keen on reading text records to understand how such relationships actually worked.

What binds the tributary relationships is a kind of symbolic order, which basically places China in the center of the universe. When all these other countries sent their missionaries to China, they had to perform very elaborate rituals, they had to kneel down or bow down to the Chinese Empire. They had to present gifts and recognize that they were lower on the hierarchy than China. Usually, they got gifts that are worth much more than the gifts that they presented to the Chinese empire. And they would, of course, have to recognize the Chinese Emperor as the universal ruler. So that is briefly what this Tianxia as a world system was. The real use of this term actually begs our attention because you hear about Tianxia these days a lot in the last ten to fifteen years with the rise of China on the global stage, and there has really been a surge of scholarship on Tianxia. Scholars like Zhao Tingyang who has published books on Tianxia and whose books have been translated into many languages really proposed this ideal form of global governance. This global governance is beyond international politics as we know it today because international politics is based on theoretically equal nation-states, whereas Tianxia is based on the harmony and common wellbeing or a common destiny of all peoples. Such recent scholarship has excited people on both the left and right. My question here is: is it actually a historically accurate practice or how was Tianxia actually used and theorized in history?

We could compare the curious trajectories of Tianxia and Eurasianism, and whether they could potentially harbor emancipatory potential

Another moment, another snapshot of Tianxia came much earlier in the 11th and 12th century with the Confucian scholars Zhang Zai and Zhu Xi, both of whom were very well esteemed scholars of the time and felt China was going through some kind of bureaucratization. They felt the country had lost the spirit that used to be there. They lamented the fact that they were no longer living in this system of Tianxia where sage kings reigned with rites and music, but now we had only schools and exams. I mean, it is not so bad to have school and exams—it depends on what kind of school or exams you have. According to them, the better moment in history is clearly where you do not even have to rule with these technocratic or bureaucratic systems, but you only have to give people rites, rituals, and music— and that would be the best-case scenario where all the peoples and everything under heaven can come into harmony together. This point—rites and music—somehow reminds me of what you have just said about “everyday confessionalism” in the geosophy of Russia. This is how Tianxia as a term and as a concept was actually used by intellectuals in history.

And another crucial moment was before the modern era, at the beginning of the Qing dynasty, which was the last imperial, non-Han-Chinese dynasty where the Manchus ruled China for almost 300 years. When they first conquered China around the mid-17th century, many Chinese scholars committed suicide to show their loyalty to the previous Chinese dynasty, the Ming dynasty, and other scholars argued that even if Qing could take over China, they could never win the Tianxia. It implies that Tianxia is a more abstract idea than the actual physical country that you conquer, it rather encompasses a cultural sphere. In that sense, it was kind of a prototype of emancipatory nationalism. This is the most explicit case. We could compare the curious trajectories of Tianxia and Eurasianism, and whether they could potentially harbor emancipatory potential sometimes. But it can also be distorted and co-opted to justify neo-Imperial practices, at other times. This is a brief overview of Tianxia as a concept.

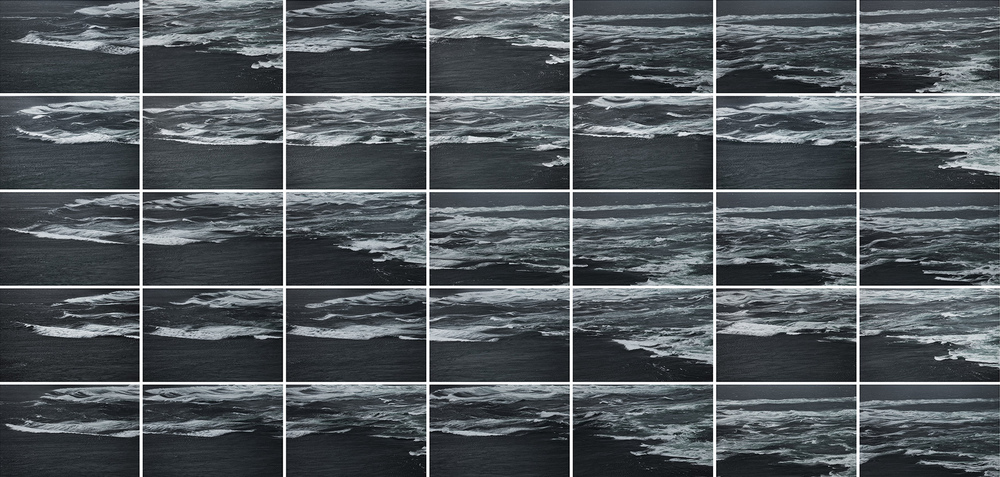

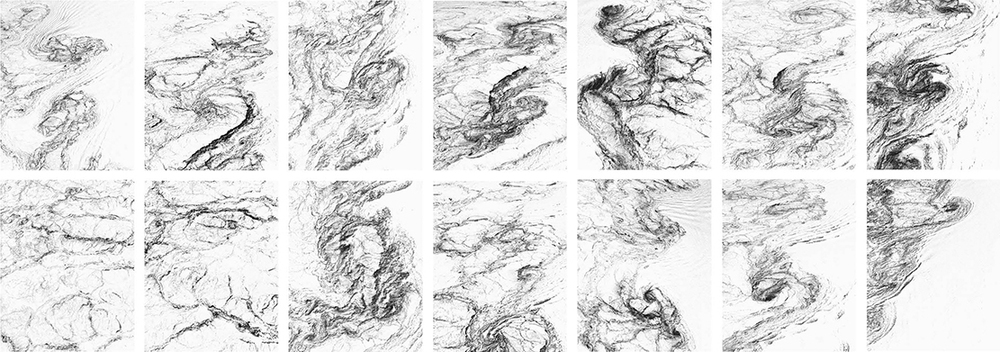

Below: Maelstrom Module Variation II – Torus

Maelstrom Module Variations are part of Into the Maelstrom series (2011–2013) by Zoé T. Vizcaíno

When it comes to military and economic questions, things get complicated. For example, if you look at how Tianxia as a world system that did in some ways contribute to peacemaking in the region both in the case of the nomadic tribes and the Chinese Empires in pre-medieval and early medieval times (albeit at great costs for China), and also in early modern time between the Ming and Qing dynasties and its East-Asian and Southeast Asian neighbors. It is true that these relationships did contribute to regional peace. There are numbers and statistics that demonstrate that there was really very little major warfare between China and these countries. This tributary relationship is equivalent to today’s trade delegations and trade treaties. In a way we can argue that something like that is going on with the BRI and with all these trade agreements and bilateral investment treaties, basically implying that China lavishly gives money to other nations. Answering your question, hard power is always behind this kind of discursive, theoretical, and philosophical soft power in the modern and contemporary context of the struggle for power, which is something that makes Tianxia quite a dubious concept.

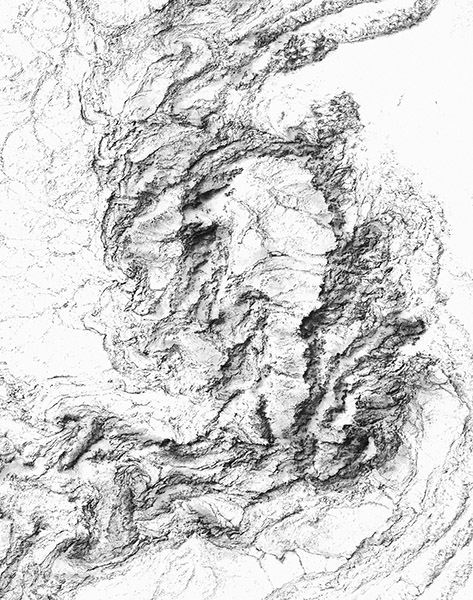

Right: Landscape Unit XIII

Down: Saltstraumen Maelstrom Cartography. Series of 15 Landscape Units

Parts of Into the Maelstrom series (2011–2013) by Zoé T. Vizcaíno

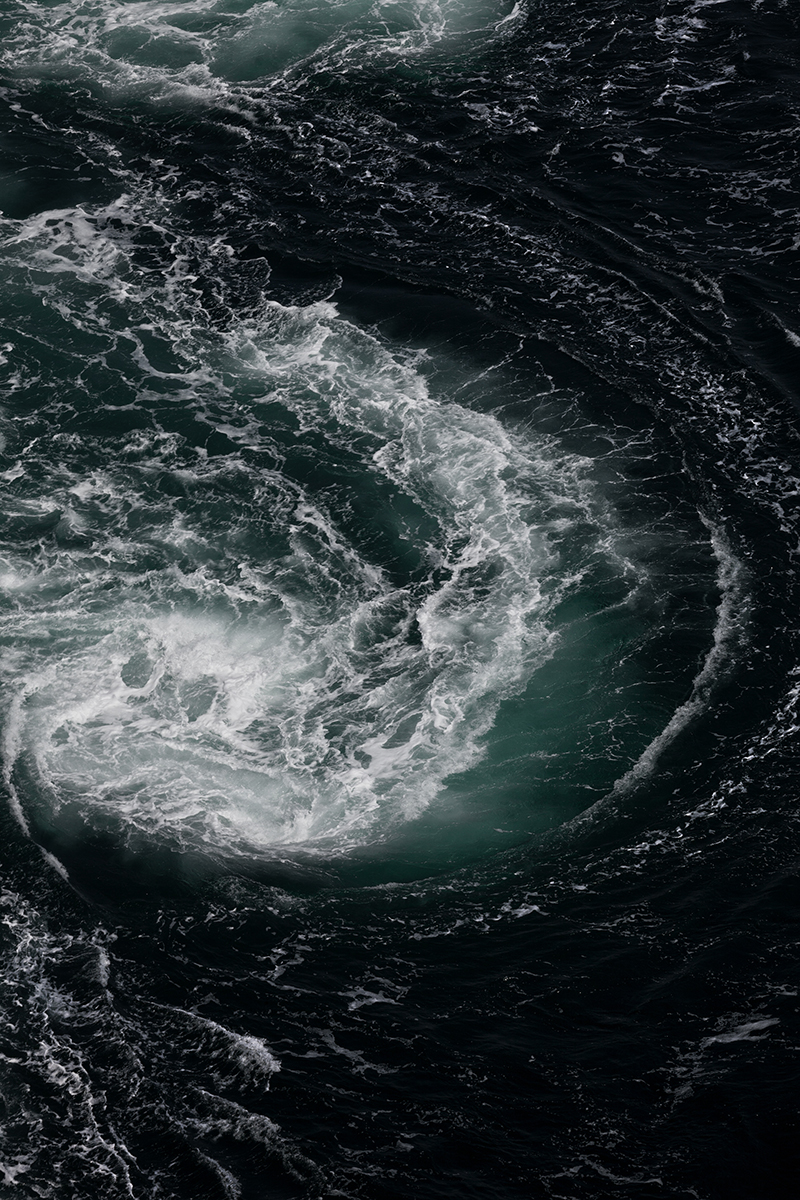

"I’m interested in emphasizing the idea of a vortex as a primary model, as a dynamic and coherent structural energy capable of generating a centripetal force that drags and concentrates matter into invisible depths. While these depths remain impenetrable, the surface perturbations, the wheeling and foaming streaked atop the sea, are ever-present records of the density and force that is drawn below."

I could also relate to what you said about Eurasianism as a prefiguring post-colonial discourse if we follow the ideas of Vivek Chibber, for example. Building this kind of both unified, but also diverse—perhaps, pluriversal—worlds seems to be only a possibility of something that is actually universal. Because you can only view such a pluriversal world if you have gone through and you are situated in a kind of Western tradition, be it in the elite Western universities or within the universalism of the global ruling elites.

I am interested in whether a non-Western philosophy is possible. Was it possible before? Is it going to be possible in the future?

I am interested in whether a non-Western philosophy is possible. Was it possible before? Is it going to be possible in the future? Does it feel almost as if that it was only possible within a certain universal structure? That is maybe the most frustrating part of being a thinker from a non-Western country and trying to understand where we are. I know you are still interested in how much of Tianxia as a modern political theory is viable. I think the most recent manifestation is not actually Tianxia itself, but the concept that is connected to it which has been adopted by the Chinese communist party as a model not just for foreign policy, but for their general policy—in the slogan “community with shared future for the humankind.” This is an idea of the common future for humanity. Curiously enough, I think they changed the English translation from “shared destiny” in the original rendering because they felt “destiny” sounds a bit fatalist, ideological, or it just doesn’t evoke the right feelings. So this common future of the humanity is connected to the ideology of Tianxia and they profiled it as an original idea as a proposition for international governance and also as a goal for society, domestically and internationally, but they never quite looked into similar ideas that had been already in place, for instance, in Germany around the circles of Carl Schmitt. It is a really complex situation: mentioning any of these concepts would evoke very different reactions or associations depending on who you are talking to and what context you are speaking from.