In his four part series for EastEast, the artist and filmmaker Rouzbeh Akhbari is posting brief dispatches from his three-month research trip in Oman. Akhbari’s interest in the region stems from his work on two related projects: research focused on how the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC) translates into local contexts near Iran’s maritime and terrestrial border zones, and an experimental documentary titled Point Rendezvou that follows the informal livestock trade between the Caspian and Persian Gulf littorals.

Dispatch 4: March-April 2024

During my final month in Khasab, my curiosity about the political economy of the informal livestock trade grew more acute. I sought to gain a deeper understanding of the logistics, labor dynamics, and material flows underpinning the complex supply chains that enable the large-scale movement of sheep and goats across the Strait of Hormuz. At the same time, I was keen to explore how the formalization processes I had previously examined were reshaping trade practices in Musandam. To pursue this inquiry, I engaged with a diverse group of port workers, truck drivers, and animal handlers, all of whom generously shared invaluable insights into the intricacies of this trade ecosystem.

Early on, I discovered that the vast majority of livestock arriving in Musandam is not intended for local consumption but bound for markets across the Persian Gulf, primarily in the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, and Bahrain. Upon arrival, the animals are typically housed in makeshift barns where they are counted, fed, and sorted according to their respective owners, identifiable by spray-painted markings on their backs. Those injured during the turbulent, high-speed journey from Iran are often slaughtered immediately, while the others await inspection by a local veterinarian in Khasab. Once deemed fit, the sheep are issued a certificate from the Omani Ministry of Health, which masks their true origin, allowing them to be re-exported to foreign markets.

I encountered a range of estimates regarding the scale of this livestock trade, with figures varying between 1.5 and 3 million animals per year. However, based on my own observations during the peak season—especially in the lead-up to Eid al-Adha, when the ritual slaughter of sheep is a central tradition—the lower end of this scale seems more accurate. Through conversations with barn workers, I learned that the demand for livestock in the Gulf region is so high that sheep are not only sourced from across Iran's vast geography but are also imported into Iran, both formally and informally, from countries like Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, with the sole intention of smuggling them to Khasab. According to those I spoke with, an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 workers are directly involved in the herding, smuggling, and transport of these animals, making the entire supply chain a significant economic lifeline for numerous families, stretching from the Caucasus to the Persian Gulf.

Many accounts pointed to how Khasab’s port construction and ongoing formalization have disrupted traditional trade. As many families lost their commercial privileges due to diminished direct access to open waters, as detailed in my previous dispatch, those interested in engaging in international trade have been forced to navigate the port authorities through middleman import/export companies. While there are ostensibly many such companies operating in the area, only a select few individuals officially possess "bahria" certificates, which grant them the authority to interact with port customs. Consequently, the implementation of strict customs regulations at the port has effectively created a de facto monopoly over Khasab’s maritime trade, solidifying the exclusive control of the wealthiest and most influential local merchants over the smuggling networks linked to Iran.

Mapping Material Connections

To ground my findings in material realities, I conducted two experiments to trace the informal livestock trade’s reach across these vast geographies. Both case studies reveal deep interconnections between crucial informal trade practices, planetary financial networks, and urban development models in Iran’s adjacent borderscapes.

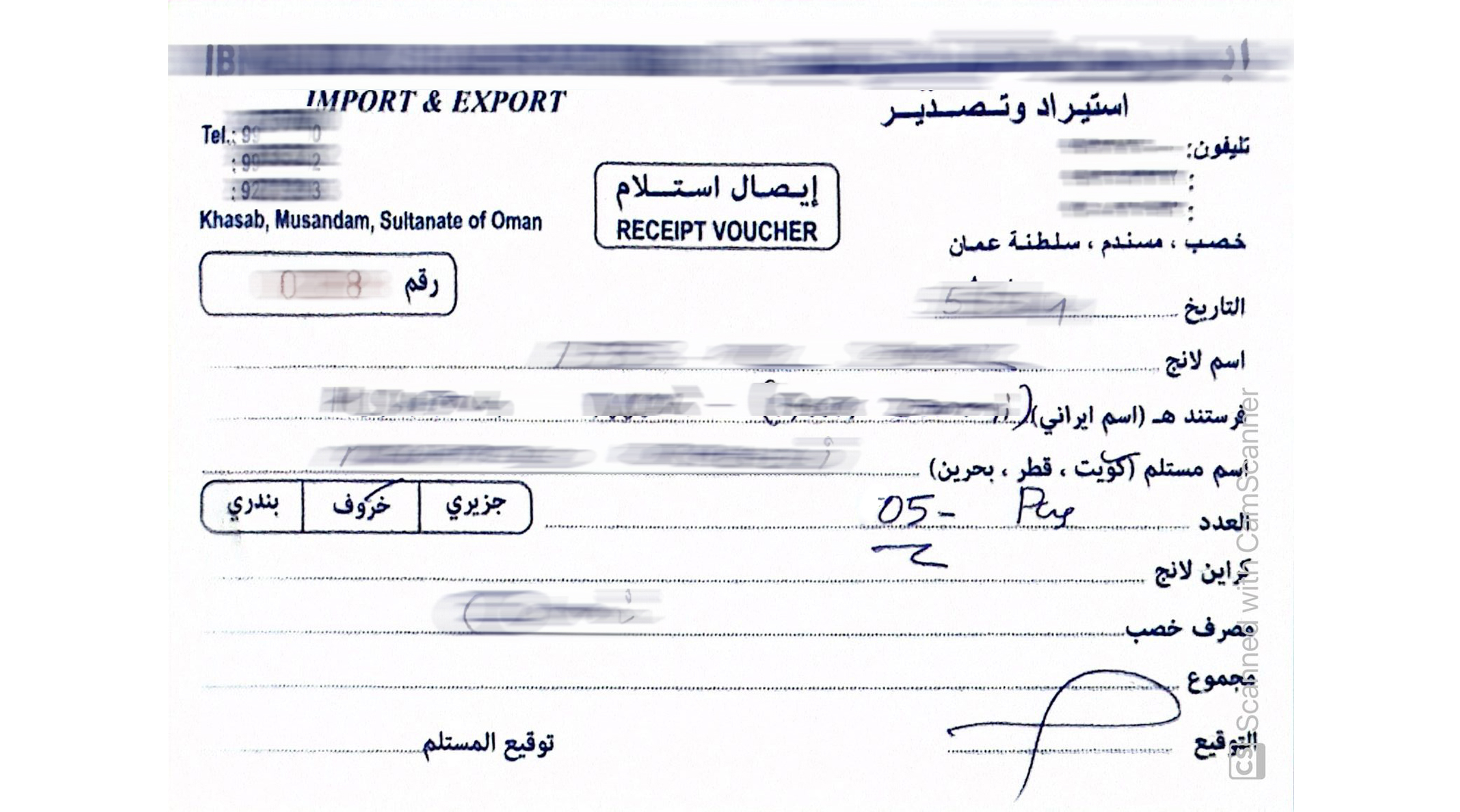

In the first experiment, I acquired a cash hawala for half a dozen smuggled Iranian sheep from one of the town’s well-established import/export companies. The promissory note detailed the importation of the animals from Iran and their eventual re-exportation to Kuwait. The sheep arrived in Khasab on two separate speedboats in early March, after which they were loaded onto small lorries and transported to a makeshift barn on the outskirts of town. There, they were fed and cared for over the course of three days. I was granted access to the barn during this period, allowing me to observe the sheep firsthand before they were reloaded onto commercial dhows dhows a lateen-rigged ship with one or two mastsbound for various Persian Gulf destinations.

After 11 days, I received an update from the company’s handlers, confirming that the animals had reached their destination without any losses. They also provided me with the location of the market in which the sheep were to be sold in Kuwait City. I arrived just in time to witness the animals being washed and prepared for the bustling auction halls. Less than a day after my arrival, the company’s agents informed me that the sheep had been sold and that the sale proceeds were ready for transfer. Once I notified them of my presence in Kuwait City, they directed me to the city’s old souq to collect the hawala, minus their commissions and transport fees, from one of the many money changers on the notorious Saud Bin Abdulaziz Street. The money changers conveniently deposited the funds into my international digital wallet within hours.

In the second experiment, I physically traced the movement of the sheep from their arrival at Khasab’s port to various barns. My intention was to identify their respective owners, which I hoped would lead me to one of the "bahria" holders who maintain a monopoly over maritime trade in Musandam. After a brief search, I discovered that the majority of the animals were taken to palm plantations owned by a notoriously wealthy merchant located in the town’s center.

Upon inquiring with the barn workers, I learned that this individual had made significant investments in several new urban development projects, including industrial plants, upscale mosques, and residential neighborhoods south of Khasab’s old city. During a visit to one of his mosques under construction, I encountered Iranian artisans and masons skillfully finishing the interiors with marble slabs that had been informally imported from mines as far away as the northern Khorasan province of Iran.

The final leg of my research—transporting the sculptures—offered one last window into the delicate negotiations that define this trade. In the following months, I collaborated closely with the mosque’s architect and artisans to create two sculptures that document and embody the logistics of informal livestock trade in the Persian Gulf littoral. These sculptures are scale replicas of the navigation beacons marking the entrance to Khasab’s new port. Distinguished by their green and red colors, these markers serve a universal purpose: ensuring safe passage by clearly delineating the right (starboard) side of the harbor from the left (port) side. Leveraging the same informal networks that facilitate Khasab’s maritime trade, we fabricated these symbolic replicas using the same marble slabs employed in the mosque’s construction. Much like the sheep, the columns were smuggled across the strait, assembled, and certified in northern Oman before being re-exported to the UAE for an art exhibition.

Through these experiments, I discovered that livestock smuggling in this region transcends mere opportunities for arbitrage; animals serve as containers of value that facilitate access to international monetary networks. For Iranians grappling with a rapidly depreciating national currency, livestock can act as a hedge against inflation. This dynamic allows individuals to trade animals for digital currencies, providing them with a means to engage with global financial markets. Such a system offers citizens in heavily sanctioned regions like Iran a chance to trade internationally and invest in foreign markets, which often promise better returns than their faltering domestic economy.

Moreover, I learned that the narrative of development in Musandam, much like in many parts of the world, reflects the realities of crony capitalism. Here, the state collaborates with powerful non-state actors to establish monopolies over long-standing organic economic relationships. In Khasab, the most prosperous players within the smuggling networks navigate the formalization processes that tie the right to maritime trade to official certifications, such as the bahria. The new mosque and industrial ventures in Khasab’s predominantly working-class neighborhoods, financed by a livestock merchant, exemplify how, despite a strong drive toward formalization, the informal trade with Iran remains deeply interwoven with the city’s rapid expansion and strategic development. This interplay highlights the complexities and contradictions inherent in efforts to formalize economic activities while also recognizing the enduring significance of informal networks.

To conclude my dispatches from Oman, I will cite some notes from a conversation with the truck driver who transported my sculptures from Khasab to Dubai:

[Male| 30-35 | Omani]

—Local Khasab resident. Sometimes works with his truck to earn extra income.

— “The going rate for Dubai delivery is 120 Omani Riyals (~$310 USD), but this is different. If it were sheep, it would be easy because the border police are used to it. These columns are suspicious. They (Emirati border guards) know we have nothing in Khasab and that everything comes from Iran. They will certainly think these columns are filled with drugs and want to break them to see inside. If you leave an extra 250 Omani Riyals (~$630 USD) with me, I will offer them a tribute to avoid any accidents . . . And if they don’t get suspicious at all, I will keep the extra money for the risk I am taking here!”