外 wai = outside, foreign

We come to experience ourselves as the “other” at different stages of our lives. Some of us grow up being “othered” and some find themselves on the side of the “other” quite unexpectedly. Rory O’Neill, a Shanghai-based Daoist philosophy doctorate student from Ireland, takes a kung fu approach to being a foreigner in China. He describes his adventures in an essay styled after ancient Chinese texts and nourished by the air-conditioned refuge of Starbucks.

“The children might be afraid of you at first, until their parents tell them you are okay,” Auntie Adult says to me, and then to the others, “Even his eyes are different from ours!” An embarrassed, shifting silence follows. Auntie Adult is the cousin of a friend and former colleague. This friend, who goes by the name of Egg Egg, showed me the ropes of a Chinese world within a London-based tech company. She made me feel at home in that Chinese pocket. Now I am eating breakfast with her and her husband in Shanghai. We are bonding in that way that many Chinese people enjoy: discussing ways to potentially make money together. We had done this happily over dinner and drinks the night before. We had it all worked out: her husband would teach sciencey stuff, I would teach English, and Egg Egg would deal with the parents. Then Auntie Adult comes along in the morning and drops a line in the business plan addressing the issue of my eyes looking different to those of my prospective partners and prospective child-parent client units.

If I were so foreign a being as you suggest, Auntie Adult, that my eyes would strike fear into the eyes of children, then I would find it very difficult to live here in China. “This is simply not the case!” I retort every now and then to the absent Auntie Adult. I never met her again, but she remains an inhabitant of my inner world. So I thought it best to give her a name. She is Adult because she has forgotten what it is like to be a child. She has forgotten which fears and judgements are built in and which are a result of culture. Children do indeed tend to fear strangers. But from my experience, I stand as good a chance as the average Chinese adult in making a Chinese child feel at ease. This is impeded, however, if adults present are feeling ill at ease with me; children are very adept at registering unease.

It is customary in China to call people of an older generation “auntie” or “uncle,” but this is not how she came to be called Auntie. She is the cousin of my friend of the same age, so she should be “sister” to me. But she is Auntie because I imagine her not as the mother of those children on whom she comments, but as the aunt—less familiar but with more opinions. I’m sorry for ranting, Aunty Adult, but you really did rub me up the wrong way.

A couple of years later, I walked out of my apartment and met a child of about two-and-a-half years old on the stairs. He said, “Uncle.” This is an appropriate, warm and friendly form of address in China for a man old enough to be one’s father. At least I thought it appropriate. His minders who climbed the stairs behind him, perhaps his grandmother and grandaunt, looked at me and then back at the child, chuckling. The kid had got it half right, apparently. “Foreign Uncle,” they corrected.

The next time I met this child in the stairwell, he was either with different minders or the minders had forgotten that incident. This time when the child called me “Foreign Uncle” his minders hesitated, dumbstruck, and then emitted excited bursts of laughter that seemed to exclaim, “How clever is this child!” How had the toddler worked out not only that this man was “uncle” but that he was foreign!? Top marks! “Foreign Uncle!” they repeated gleefully, “Foreign Uncle!”

With both occasions clearly imprinted on my mind, it was clear to me that the child had performed no feat of deduction, as he had done the first time when he called me “Uncle.” The second time, he was simply matching the phrase to the face that came with it when he had learned it in that same stairwell. Outside of this stairwell and beyond this one foreign face, however, I had no insight into the development of this child’s sense of inside/outside.

What is kung fu? The word means something between “time” and “effort.”

I thought it meant Bruce Lee doing a flying kick!

It does. But how does Bruce Lee get to do a flying kick? Through time and effort. Through physical, mental and, perhaps, spiritual cultivation.

Loosely defined, kung fu is something that takes time and effort, or it is the time and effort itself. Time and effort require patience. Patience requires a checking of impulses and desires. Those impulses relaxed, we become less do-ers and more receivers of the world. Have you ever watched a patient person in conversation? Does he or she feel the need to interject every thought that occurs to him or her? If her interlocutor says something silly or inappropriate, does she make haste to reprimand the speaker? Maybe she would allow the silence and embarrassment the speaker created to do the work instead. If a punch is thrown at Bruce Lee, does he respond by exerting greater force than the thrower of the punch? Maybe, but ideally he would conserve his energy and use the force of the punch against the thrower. I want to tell you about my finest kung fu feat, but let me tell you first about a couple of places I have lived.

After spending a couple of years in China and a couple of years in London, what made me come back to China again? London shares a lot more culturally with where I grew up than does anywhere in China. But I missed that feeling of foreignness. I wanted things around me to be foreign, and I wanted to be foreign to them. More foreign. Why? Maybe because when you are supposed to be not foreign—i.e., relatively at home—but don’t feel quite at home, then there is something wrong. But if you don’t feel at home when you are supposed to be very foreign, then that’s fine. It can even make you feel quite at home. Emmanuel Levinas wrote about how recognition of the other is the beginning of ethical life. He thought that even in a marriage, due respect should be paid for the otherness of the spouse. Constant recognition of the other as other was part of Levinas’ vision for a harmonious family life, and his dream for a harmonious society.

– Where are you from?

– Ireland.

– Your Chinese is very good.

– No, no.

– How long have you been here?

– [X number of] years.

This conversation is a constant feature of being foreign in China. When buying vegetables, I am the guest of the vegetable seller, and am happy for her to engage me in this conversation. When looking for a particular-sized allen key, I am the guest of the hardware store owner, and am happy to have this chat with him. Having already engaged these people in transactional relationships, I am happy to extend these relationships socially, within reason. There are boundaries to these semi-social occasions, and I have learned to defend those boundaries.

During my bachelor’s degree in Ireland, my weeks were occupied by studies and a part-time job. In addition, I would have at least one night of heavy socialising, and one afternoon that would be my sabbath. The sabbath was spent in the post-Christian existential church: the self. Angst would be turned into atmospheric moodiness through ritual activities, including: wandering aimlessly and alone, drinking coffee, smoking rolled up cigarettes, and reading scraps of philosophy and poetry. I was time-rich then. Now, I no longer have the luxury of the weekly existential sabbath. But I will sometimes find myself alone and angsty of a grey weekend midday. And I might remedy this with a walk through the local centre here in the outskirts of Shanghai, to experience the self amidst the ambience of other people’s lives.

On one such day, half in my mind and half looking out, my eyes strayed left and right of the path before me. They met the eyes of a man who must have seen me coming from afar. He was ready. His face, already in a half grin, quickly morphed into a full smile. Veering towards me, his English practiced and strange, he boomed without pauses or inflection, “HELLO SIR HOW ARE YOU.”

I responded in a low voice and neutral tone, “Fine, thank you.” And I turned my eyes back to the safety of the centre of my path. My dullness contrasted with his vivacity like yin and yang, preventing any further possibility for conversation. There was no surprise, affront, nor friendliness in my voice. It came without hurry or pause, without effort or strain. The connection between us was instantly and powerfully diffused. This was my kung fu response.

Yes, I am proud. Modesty is a virtue of kung fu masters, so maybe I am not at that level yet. In the past I might have grappled for an appropriate Chinese phrase with which to respond—throwing the man for six with a biting lash of his native tongue. Or I might have stared him down, injecting him with all the venom of someone who had been reminded daily for many years of his foreignness. Or I might have punished him with silence for disturbing the sanctity of my church. But to respond in Chinese would be to fish for a compliment. To stare him down would provoke a further response to defend his ego. To ignore him might aggravate him into launching another verbal missile.

My response was conversation diffusion kung fu. It was pure self defense without an element of attack.

Starbucks is bad. This is a well-known fact amongst cultured individuals of the West. I am no longer a cultured individual of the West, so I have forgotten this fact.

I first lost this knowledge when an Irish friend came to visit and we took a trip in Southwest China. He surely had a different vision of the real China to mine, but both were probably along these lines: tea from china pots, stuff made from bamboo, meandering pentatonic music, zig-zaggy tiled roofs, and calligraphy on the walls. Searching for this was tiring at times. Especially when it was hot and we failed for long periods to get out of wide faceless streets to the real China beyond. One afternoon, we stopped into a Starbucks in Guiyang, the capital city of the mountainous southwestern province of Guizhou. We sat for an hour or two. The next day, when deciding how to spend our precious last day in Guizhou, I was surprised and ashamed by how agreeable my friend’s suggestion seemed to me: Let’s go back to Starbucks.

We returned to see Lady Starbuck smiling benignly from Her green circle, hovering above the doorway and printed on every cup. In all aspects—flavour, air temperature, music, prices—She radiated sameness and predictability. Her employees did not inquire about our nationalities. The layout of Her furniture encouraged a preservation of personal space. Lady Starbuck created a general atmosphere of keeping to oneself. We were converted.

My parents coming to China in the autumn of 2017 was one of the greatest experiences of my life. It was such a wonderful mix of two homes. We spent most of our time seeing the real China, but found time for a coffee every day. My dad made it clear from early on that we were not going to Starbucks. In Shanghai, we easily found coffee far superior to Starbucks, and in settings far more unique. In the tourist area of Beijing, too, we found little cafés, though the coffee would have made me choose Starbucks.

From Beijing we went more remote. Clumps of the Mud Great Wall can still be found on the border between Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. I read on a Russian guy’s blog that you can take a taxi from a small town called Fengzhen in Inner Mongolia to find some of those mounds. They lay beside an old walled village that once served as a trading zone between the North and South sides of the wall. It was refreshingly undeveloped. I saw an owl in flight for the first time in my life. Its head looked too big for it to be able to soar like that. We walked around from morning until late afternoon, stopping at lunchtime to snack on a few things we had brought.

We found a taxi back to the little town and asked the driver if he could take us somewhere that had coffee. He spoke into his intercom in the local dialect for about ten minutes. I only understood the word for “coffee,” which popped up every now and then. He and his team on the other side of the intercom successfully guided us to the only coffee establishment in town. It was empty apart from us. Dimly lit, it had the air of a place people would take clients or business partners to seal deals. We ordered coffee and drank it, updating our travel log. Dad nodded off to sleep. Mum looked at her iPad. I stood up and, alone, stared out the window at the grey rain that had started. Bette Midler sang The Rose through the café speakers. The lyrics seemed unbelievably sad. This was grim. But it had coffee.

We got back to the real China after that. We had dinner in a restaurant that housed the remnants of a wedding. The waitress ushered us into an enclosed room, sheltering us from the festivity. But my mother insisted we eat in the main hall (at a certain distance from the wedding tables) to experience the lively atmosphere. After our meal, the staff invited us to take pictures with them and the jolly wedding participants.

Our experience of the real China continued elsewhere in Inner Mongolia. But the cafés—our native reality—became scarce. The capital, Hohhot was not at the scale where locals could drive us to the only café in town, nor was it globalised enough yet to be dotted with independant cafés. So Dad grudgingly accepted Starbucks as the only reasonable option. As we sipped our coffees and ate our little cakes, the penny dropped: our daily coffee was our piece of normality and all we needed was something predictable that would meet our most basic coffee needs. Lady Starbuck had converted again.

When I was teaching English in Sanya, Hainan province, my colleagues and I needed sanctuary from the stares and hellos that met us in the streets. We would sometimes sit by the river. The breeze offered some relief from the heat. It was usually a quiet place where we could sit and mind our own business. But sometimes people would come and mind my business for me, delving into questions of where I was from and what I was doing there. Call me a control freak, but I liked to deal with those musings in my own time. Nobody in Starbucks asked where we were from, and when 38°C humid heat prevailed outdoors, the breeze of the river was no match for Her air-con.

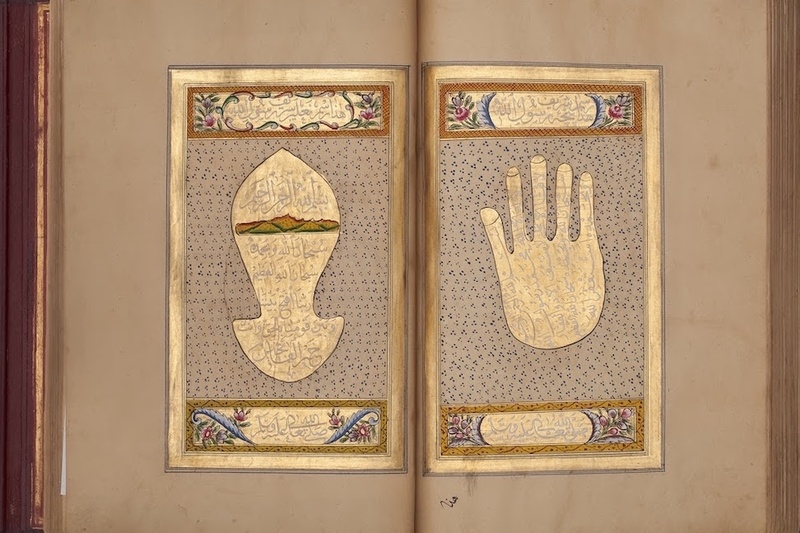

We came for the standardisation, but Lady Starbuck did allow for some human touches. This Sanya Starbucks followed the centrally approved practice of writing customers’ names on cups. For me, they wrote variants of Rory: Lory, Roly or Roy. One day I looked at my Irish colleague’s cup to see a single character 外 written there. I pointed it out, and it took her a moment to process that 外 wai = outside, foreign. Oh! She laughed. And she posted it excitedly to her WeChat Moments with the caption, “Starbucks, you really know how to make a girl feel at home!” This was localisation at its best: the bland experience of a standardised corporate giant, with just a touch of indigenous character.

Thank you, Lady Starbuck.

It is right to give Her thanks and praise.