Fashion designer Lorin Mai, born to a Russian mother and a Syrian-Kurdish father explores her family history and cultural heritage through her brand Vertigo, creating not only clothes but also objects at the intersection of art and design.

Lorin's latest collection, inspired by the Yasna ritual, showcases handcrafted objects that look into the ritual's dualistic nature—blurring the line between the spiritual and the mundane. In an interview with Anna Mikheeva, Lorin shares her approach to design, which she sees as a powerful medium for delving into complex concepts and creating a sense of belonging.

I launched my brand Vertigo after graduating from The British Higher School of Art and Design in 2019. For five years, I've been exploring my identity through fashion collections and special projects within the brand. Recently, I've focused on studying archives and research methodologies to gain a deeper understanding of my family history and share Kurdish cultural heritage.

Working with other designers, especially with Zhenya Kim, has been eye-opening. It helped me find new ways of working with cultural codes and implementing valuable parts of my ethnic and national identity in my design projects. Vertigo began as a personal journey of self-discovery and cultural exploration. Over time, its mission has evolved. Now, I see this project as an attempt to foster new connections between people while strengthening their sense of belonging.

In 2022, TUMO Studios—a nonprofit educational program that invites international professionals from various fields to lead workshops—invited me to Yerevan. There, I conducted a month-long workshop as a fashion designer, guiding students in creating their own fashion collections.

In Yerevan, I delved into the intersections of Armenian and Kurdish cultures. Armenia, especially Yerevan, has long been home to a significant part of the Kurdish population. Many Yezidi Kurds, whose religion blends elements of Islam, Christianity, Judaism, and Zoroastrianism, continue to reside there and influence the local cultural landscape. In 2019, the world's largest Yezidi temple, Quba Mere Diwane, was built in Armenia. That's why it was important for me to encourage workshop participants to explore this rich context of intercultural interaction: the connections between Kurdish and Armenian identities, the evolution of Kurdish–Armenian relations during the Soviet era, and how our peoples grapple with traumatic histories of genocide and persecution. Ultimately, the workshop aimed to discover new design strategies and visions at the intersection of Armenian and Kurdish national codes.

One of my most intriguing discoveries was the Kurdish program on Soviet Radio Yerevan, which broadcasted news relevant to Kurds in the kurdish language. My father, who spent his early childhood in Syria, recalls his mother tuning in to Radio Yerevan. While the news was inevitably presented from a Soviet perspective, the Kurdish program eventually expanded to include a music section. Notably, it featured field recordings of Yezidi chants made by Jasme Jalil, daughter of the radio's founder. These recordings are still preserved in Radio Yerevan's archives.

The more I learned about Yezidism in Armenia and its Zoroastrian roots, the deeper my interest in Zoroastrianism grew. This led me to the Multimedia Yasna Project(MUYA), which studies both oral and written traditions of the Zoroastrian Yasna ritual. The project includes a comprehensive video recording of the ritual, with detailed descriptions of each object's role. Fascinated by the ritual's material aspects, I focused my collection on the Yezidis in Armenia, highlighting Zoroastrian elements in the Yezidi religion.

One of the rituals I wanted to spotlight is the Yasna ceremony—a Zoroastrian ritual that intertwines the divine and the mundane. In my new Vertigo collection, I aimed to capture this duality, showcasing how everyday objects can carry deep ritual symbolism. I created several handmade pieces that, I hope, will give people a sense of both the physical and spiritual dimensions of the ritual.

Right: Lorin Mai, Flycatcher, a common household item that symbolizes humanity's "third hand." In the "Yasna" ritual, a similar ladle places sandalwood into sacred fire. This object embodies dualism, representing both existence and non-existence through the beaten fly and burnt wood.

During the ceremony, two priests prepare the sacred drink of immortality, haoma. Fire plays a crucial role in this process. Thus, I incorporated a vase—one of the ritual's key attributes—into the collection. The vase elevates a metal dish where the sacred fire is kindled. I also included a metal fly swatter, representing the spatula priests use to toss incense like sandalwood and frankincense into the fire.

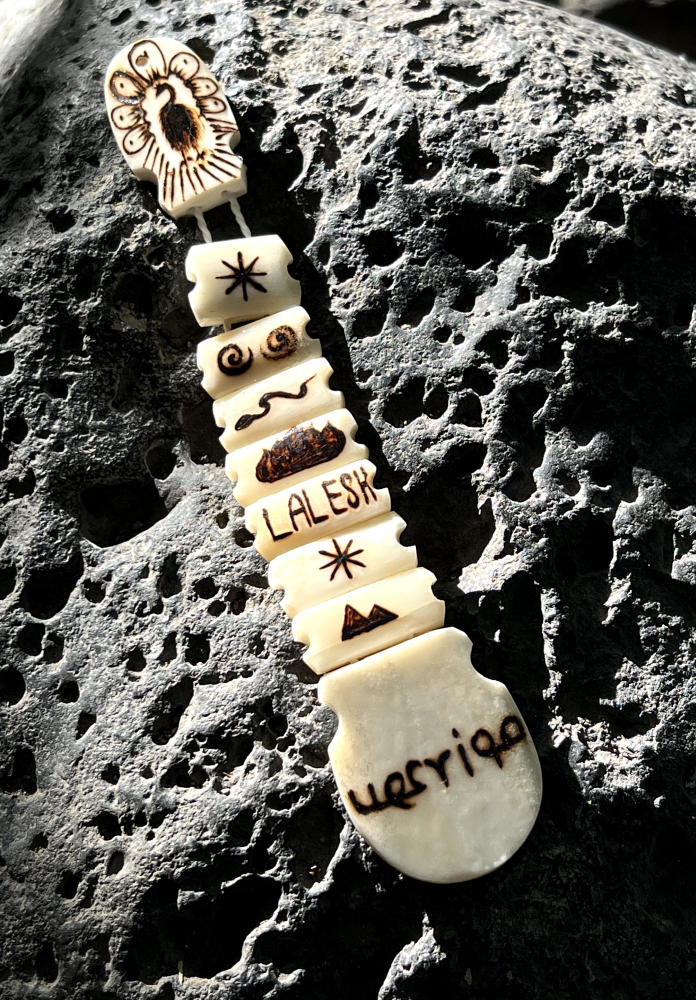

A unique place in the collection's narrative is occupied by the Yezidi "thieves in law." Some, like Ded Khasan and Shakro Molodoy, wielded considerable influence beyond the South Caucasus, instilling fear in many former Soviet bloc cities. I wanted to address this aspect of the Yezidi community in Armenia as well. In prison culture, flip rosary beads symbolize timelessness, helping to seemingly shorten endless sentences. At a Yerevan vernissage, I encountered a rosary bead seller. Their products already featured Yezidi symbols, so I inquired about commissioning a rosary incorporating additional symbols from my collection. The seller agreed, revealing that he orders these rosaries from prisoners. I sketched my design, which was then sent to a prisoner who burned the symbols onto the rosary, using ivory billiard balls as material.

Right: Lorin Mai, Flipping Beads (Perekidnye Chetki) used by Yazidi Thieves-in-law to pass time in prison. Each bead features a significant Zoroastrian symbol: holy fire, "Lalish," snake, sun, spiral, and the peacock angel Tawûsê Melek.

At Yerevan vernissages, I discovered numerous artisans and commissioned several objects for the exhibition, including a backgammon set. This piece incorporates traditional Yezidi and Zoroastrian symbols, such as icons of the four main elements and a peacock—the symbol of Tawûsî Melek, believed to represent the diversity of the world. Significant to me personally, I added a spiral emoji—the project's central motif and a character that represents me. Backgammon itself can be viewed as a ritual, echoing Zoroastrianism's concept of dualism: the eternal struggle between good and evil.

Backgammon is widely perceived as a hypermasculine object, particularly popular in the South Caucasus, West Asia, North Africa, and the Balkans. In all these regions, the game unfolds within a distinctly masculine space. Like rosary beads, backgammon represents extreme masculinity. In the future, I hope to explore this theme through the lens of an atelier, where men come to commission suits meant to last a lifetime.

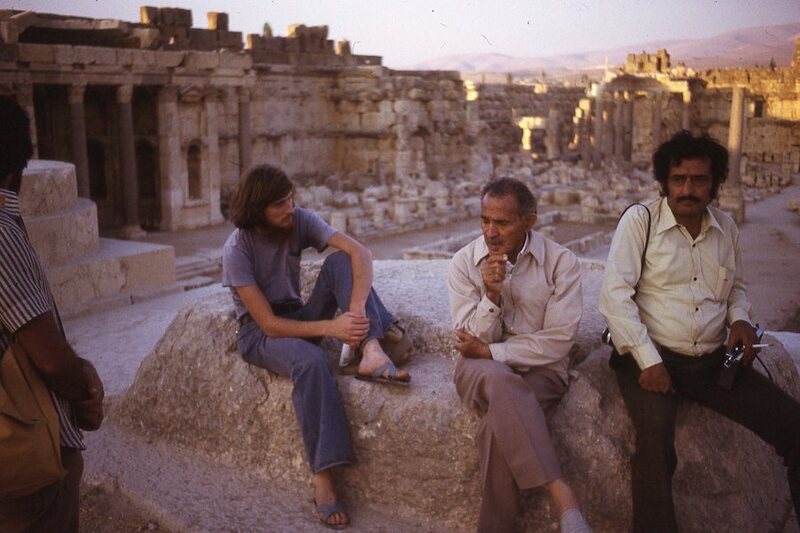

Lacking both funds and connections to engage a curator, I took on both roles—participating artist and curator. As a curator, I decided to invite photographer Eugenio Grosso to exhibit his project about the Lalesh Temple, a Yezidi pilgrimage site. His photographs naturally complemented my narrative about Yezidi Kurds. Sharing this aspect of Kurdish culture is vital to me, as Yezidism and Zoroastrianism represent forms of resistance and identity preservation for many Kurds against the backdrop of dominant Islamic culture. Following the mass Islamization of Kurds as early as the 7th century, these religions now symbolize a connection to ancient history and serve as a source of cultural pride.

From the outset of planning the exhibition, I knew I wanted to go beyond fashion and clothing—I wanted to explore other media. I was really excited about working with artisans and learning about various production aspects. Right now, I'm trying to figure out the market for these kinds of objects: understanding pricing mechanisms, and identifying galleries that specialize in such pieces, that are straddling the line between art and interior design. However, I'm still at the beginning of this journey. The need to relocate frequently as an émigré complicates matters, making it challenging to transport these pieces—hence my desire to find them permanent homes soon.

Right: Lorin Mai, a detail of the Flycatcher.

Looking ahead, I plan to continue working with Kurdish heritage. My current focus is on dengbej—a form of Kurdish a cappella storytelling. I've teamed up with an independent label that specializes in documenting and artistically interpreting hybrid genres and cultural phenomena. One of the big things we're planning is an expedition to Kurdistan. This research will culminate in the publication of a book about dengbej. As for new materials, I'm really keen on experimenting with stone in my work. This desire is to a great degree inspired by Armenia and its tuff masters.

While I'll keep creating art objects, fashion and clothing remain crucial mediums for me. It's a very powerful tool for storytelling and sharing cultural heritage. I've begun work on a menswear collection that speaks to the harsh realities of Kurdish kolbars—"smugglers" who risk their lives carrying heavy loads across dangerous Kurdistan border areas. Kolbars not only endure the physical strain of carrying 25-50 kilograms but also face constant threats from Iranian military and Turkish border guards. This new collection will further my exploration of class differences and the symbolic role of men's attire.

Right: Lorin Mai, The Vertigo Hanger, part of the "Class Message" collection, that honors atelier craftsmanship.