“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Esme Allen

Julia Watson is an designer, educator, author, and a leading expert on nature based technologies for climate resilience. Her book, Lo-TEK; Design by Radical Indigenism, builds on indigenous philosophy and vernacular infrastructure to generate sustainable, resilient, nature based technology. Visual selections from the book, along with short extracts from a conversation between EastEast and Watson, illustrate the viability, ingenuity, and new paths towards the accessibility of millennia-old human engagements with nature.

DEFINING THE MISSION

Lo-TEK is a movement that looks to existing knowledge, practices of traditional and indigenous communities, views them as systems or infrastructures, and considers how they work as climate adaptation technologies, rather than cultural heritage or agricultural heritage systems.

This creates a whole new lens of understanding—new ways of looking back at indigenous origins—given that we live in a different world from that in which they were first conceptualized.

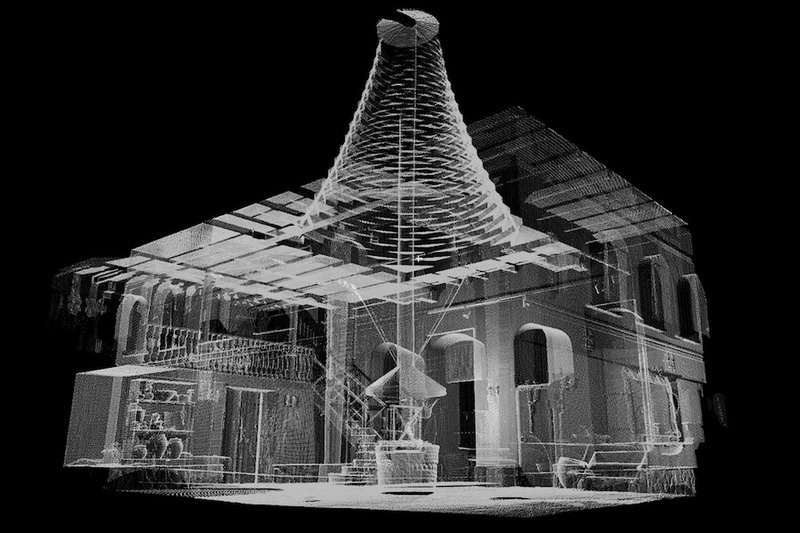

With Lo-TEK, I document these technologies through the graphic language of architects and urbanists, the people who are involved in the built environment, one of the first times in which most of these systems have been documented in that manner. This means that one can re-contextualize them or determine their new applications in a different environment, be that migration, or hybridization with a high tech system, whether it's material technology, process of construction, control mechanisms, or data monitoring. Through this process we can work to expand our current toolkit and consider what resilient systems are available; we can then implement them as a means of addressing the current climate changes occurring.

Above: The sphere of daily life for Marsh Arab women is shrinking as the reeds they traditionally cultivated slowly vanish.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Carolyn Drake

Below: Al-Tahla Floating Islands of the Ma'adan, Iraq. Methods of mudhif construction developed thousands of years ago, are still used today.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Agata Scowronek

VIABILITY

The Lo-TEK movement is viable because it already exists. It exists in local conditions: it is literally composed of the DNA—culturally, physically, and spiritually—of the land, the community, the materials in the locations in which it exists. It has already been shaped by the systems of flow and energy in those landscapes.

NEW APPROACHES

Architects, designers, urbanists, and any built environmentalists, have often developed negative reputations for their work in locales outside of the “global north,” even in cases when they have approached the environment with altruistic intentions in mind. At the root of the problem is the application of our expertise to locations where we do not acknowledge the experts that already exist in those places, the knowledge keepers in traditional communities who consider themselves as much as part of their environment as the trees, the rivers, or the rocks. We have developed a neo-colonial approach to the ways in which we design.

Lo-TEK works to recalibrate that type of thinking through a new theorization of what design can be, providing alternatives and emphasizing the fact that we need to work differently in these contexts.

Above: The view over Mahagiri rice terraces, which form part of the twenty-thousand-hectare sacred subak system.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Steve Lansing

Below: Thousand-year-old earth walls known as bunds stabilize the subak system.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Hemis / Alamy

PRESSING CHALLENGES

A chief concern is the process of, and potential exploitation inherent in, the extraction of indigenous knowledge and information. There are best practice ways of working and researching with indigenous communities, but there is also a global conversation that is really being led by indigenous communities and indigenous scholars. There is a gradient of consideration within those communities, as they ask: what do we want to do? What do we want to share? How do we share in the best way? And what do we get in return for that sharing? It can run from a very extremist point of view, to a view that is incredibly embedded in allyship. Many of the indigenous writers and researchers truly understand the value of the information, knowledge, and systems that indigenous communities have developed over thousands of years. They are the translators for non-indigenous people who, through a diminishing cultural awareness of its value, have lost that understanding.

The greatest challenge is to select the right space in which to have a conversation that is positive and beneficial. In the conditions under which this research was conducted, it was my primary intention to foster these conversations in an environment of allyship, with an understanding that we are all in this together. We should be led by indigenous people and consider them our elders, the older children of the Earth, to place ourselves in the position of younger children because there is so much that we really do not know.

Above: Water-conserving waffle gardens at Zuni Pueblo in New Mexico circaa 1910–1925.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Jesse Nusbaum

Left: Cellecion Star Dancers performing traditional dance pieces at Dowa Yalanne Mesa.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © Tom Kennedy

Right: The As:hiwi, as the Zuni call themselves, live in an arid landscape known as the Zuni Pueblo at the Four Corners.

“Lo-TEK, Design by Radical Indigenism,” by Julia Watson, published by Taschen © New Mexico

THE Lo-TEK CURRICULUM

One of the next steps for Lo-TEK is to create a platform for knowledge sharing with non-indigenous communities. It started, in a varied form, through what we are calling the Lo-TEK Living Curriculum, which is designed to inclusively improve environmental and climate literacy. This is an online curriculum and digital database, which forms an incredible archive of contemporary artists, storytellers, technologies, and projects that addresses nature based infrastructures. It is beginning to establish critical relationships in which people can learn from one another; part of the role of the database and curriculum is to serve as a space where the online community can come together and start to converse with one another.

All images provided by Lo-TEK