Wikimedia / Public Domain

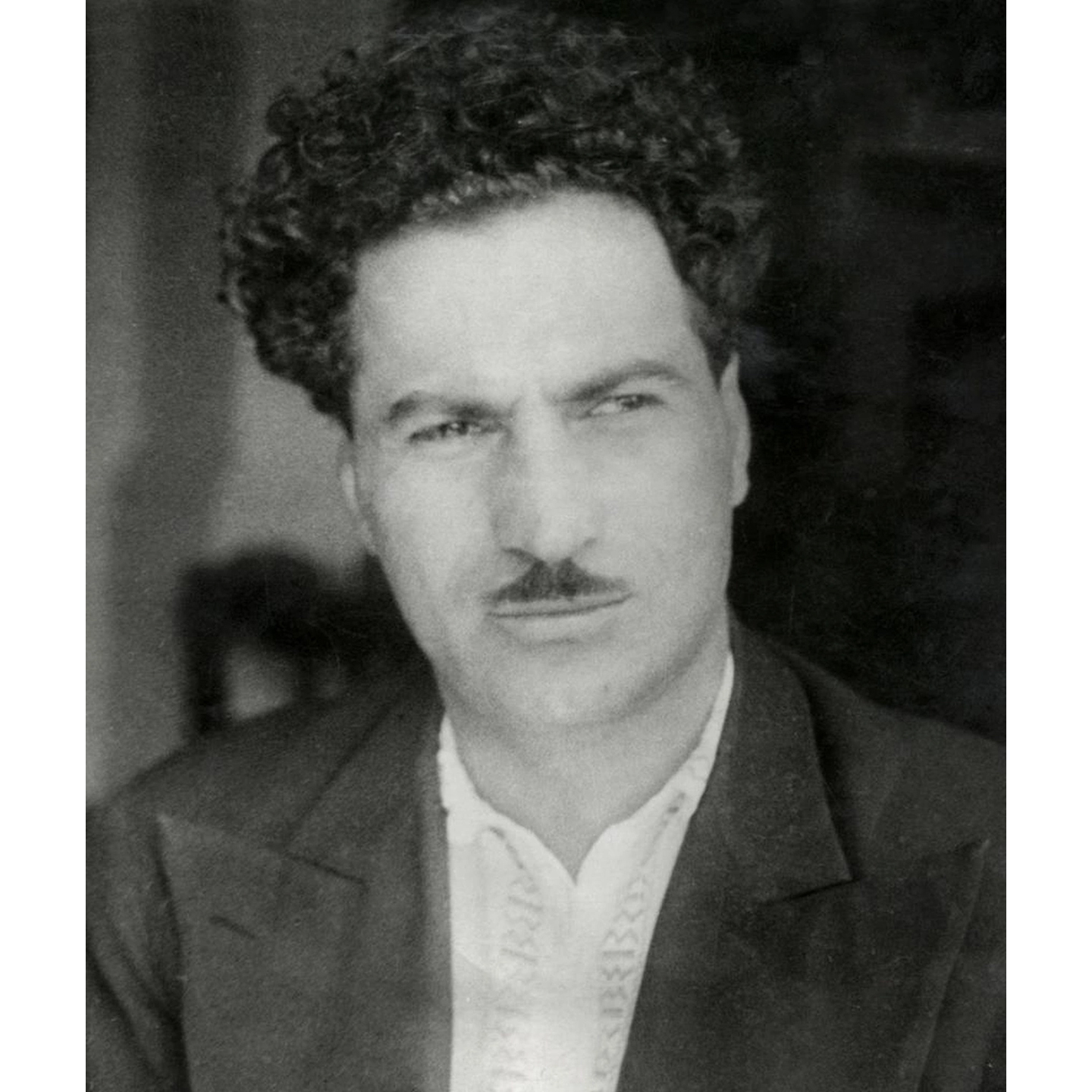

In collaboration with the Slavs and Tatars residency program, we introduce an essay by Georgian multimedia artist Mari Kalabegashvili about the idea of establishing a “Georgian Circus” meant to break down the barriers between art, cultural events, and daily life. This concept was developed in 1924 by film director Nikoloz Shengelaia, a member of the radical art collective H2SO4.

Those interested in the history of Georgian fine arts are well-acquainted with the first Georgian futuristic magazine, published on May 25th, 1924. A collective of artists and writers, under the name “H2SO4,” released a single edition that united poems, declarations, articles, and drawings with the principles of Dadaism, Constructivism, and Futurism. The group aimed to cleanse the Georgian art and literary scene with a metaphorical solution of sulfuric acid, representing Futuristic art. Members of the collective, with varied experiences, believed the Georgian art scene was far distanced from contemporary developments and that a transformation was necessary to synchronize forms of research, tempo, rhythm, and energy with its time and environment. In response to recent confrontations and the new demands of the era, the rebellious young Modernists used experimental methods such as word montage, performances (reading poems on streets or from trees), a cult of technology, and visual play with advertising banners.

One member of this radical collective, film director Nikoloz Shengelaia, published an article laying the foundation for the idea of establishing a “Georgian Circus.” “It is not surprising that the initiative to establish a Georgian circus has been undertaken by H2SO4,” he wrote in a modernist magazine nearly 100 years ago, although the initiative was never realized. Shengelaia discussed the circus as a completely hitherto unknown system, rejecting its common boulevard understanding. He defined art as the organizing structure of life and began his text with a critique of the Georgian theater and art scene, expressing concern about the lack of a diverse audience and the distance between daily life and cultural events. He wrote, “Circus lives—with life,” and proclaimed the establishment of the initiative as essential for unifying the masses and the actor. The circus was to be called Khedeira, a term derived from the word for something to be seen (სანახაობა/sanakhaoba), according to Niogol Chachava.

National Archives of Georgia

From today's perspective, discussing the Georgian circus might seem surprising, especially since the Tbilisi Circus building on Heroes' Square, which was intended to host performances, is now nearly non-functional, and the relevance of circus performances in the local environment has diminished. During the Soviet era, circus performers were seen as role models for youth, embodying both physical and moral virtues. Performers, particularly those in the conversational genre, were expected to reflect ideological ambition, relevance, and a connection to everyday life in their acts. The circus was intended to be an optimistic, diverse, and joyful art form that inspired and educated the Soviet people. However, since the local circus was never rebranded to fit the contemporary needs of society, it has lost its relevance.

However, in the twentieth century, the feeling of surprise and excitement was an important task for avant-garde artists. Circus performances were so popular in Tbilisi that temporary shows were held in almost all districts of the capital. Before its recognition as a creative field in its own right, in the 1910s and 1920s, the elite or higher members of society openly avoided attending performances. Alexander Kuprin wrote to Anton Chekhov in 1903: "In our enlightened times, it's a shame to confess my love for the circus, but I dare to do it." Shengelaia in the manifesto also echoed this sentiment: "For the actor, the circus performance turned into a shameful event. At least that's the sentiment today. This must be eradicated." For many years, Tbilisi circus ensembles were leading throughout the Soviet Union, but they could not withstand the crisis caused by the regime's collapse. Considering the historical context, when the separation of low and high culture art was still relevant, the application of the Dadaist collective H2SO4, which openly opposed existing societal frameworks, would be tantamount to a slap in the face of the so-called cultured society.

The main goal was to encourage mass action, while its charm was depicting the dynamics of the city without being distanced from it, as “here the boundaries between creativity and audience involvement are minimized.” Shengelaia believed that folk art was closest to this initiative, as it allowed the great collective of people to expose their true selves. He proposed using Georgian “primitive cultural elements” (such as horsemanship, sword fighting, SazandariSazandariA musician in an ensemble of instrumentalists from the South Caucasus that perform along with a singer. The trio format usually consists of tar, kamancha, and a daf player., Shairoba ((improvised poetry)), acrobatics, etc.) as abundant base materials for reworked and improved stage work. From the manifesto, we learn that the circus had more resources and freedom to include different artistic fields than other, more rehearsed forms.

The desire of Georgian modernists was not only to recapitulate existing works but to search for original forms of expression rooted in native narratives. The exotic name “Khedeira,” chosen for the Georgian circus, seemed aimed at a foreign audience; accompanied by a self-ironic or rebellious attitude, it provided important ground for discussing current political and social issues in today’s artistic context. Several questions arise: how can art reach a wide audience, and how important is the moment of exchange? Where does the local environment stand with the Western context, and how relevant are past experiences in the present?

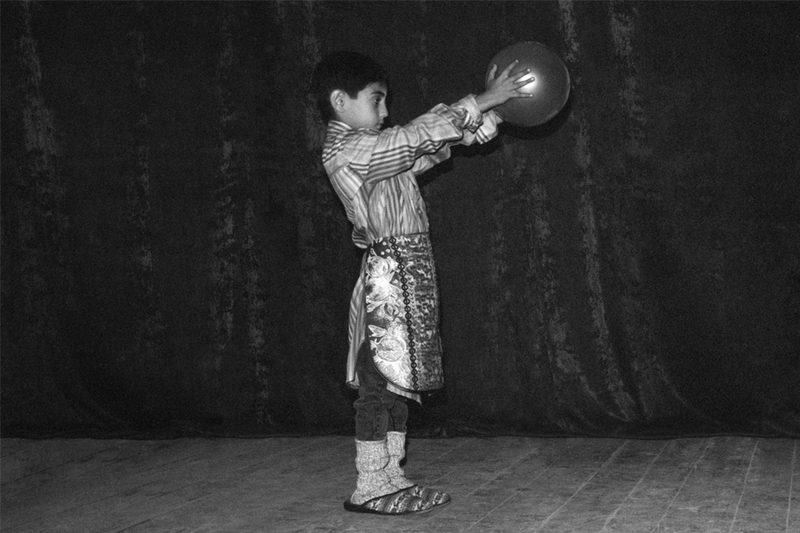

Photos of a performance by Georgian circus performers from the magazine "Soviet Circus," August 1958

The initiative took on an organizational role and sought to create a new determination and collectivism, but despite the efforts of the H2SO4 collective, no attempts to realize their project appeared. Despite their ambition and enthusiasm, the members of the avant-garde group were not spared by the communist regime. In 1928, the authorities ended the relative freedom of various literary currents still tolerated in the Soviet Union. After that, some artists continued their work under the new regime's censorship, while others faced execution, became factory workers, emigrated, or succumbed to depression.

The manifesto, at the time, referenced the reading of Russian and French newspaper sources, where we read about their impressions on the works of Jean Cocteau and Vsevolod Meyerhold, who, in their words, eliminated the ramp (the space between the actor and the audience in the theater) and developed mass actions; and Sergei Eisenstein, who combined the mediums of theater with film. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the severe financial crisis, and the disruption of state subsidies made it impossible for the circus to operate at its previous capacity. In the end, neither the Georgian Dadaist initiative nor the actual circus art form could withstand the test of time. Thus, the idea of the proposal became irrelevant, leaving us only to rummage through the archives.

Sources:

ქართული ცირკი (Georgian Circus). (1924). H2SO4, 43.

რეხვიაშვილი ჯ. (2020, May 28). ცირკია, რა! რადიო თავისუფლება. https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/30638326.html

The text was part of Mari Kalabegashvili's performance “Tracing Absence” in the framework of Slavs and Tatars residency program. The residency and event were supported by IFA.

The text is part of a series in collaboration with Pickle Bar, Berlin in the framework of their public programs and editorial platform.