The sounds of Cinna Peyghamy, a deft and exciting tombak player who merges the Iranian instrument with modular synthesis, feel pioneering and experimental, yet simultaneously grounded and organic. His performances and recordings illustrate the real potential of synthesizers not as simply as machines for the creation of new sounds, but as a facilitator of real sonic partnership. For our music issue, EastEast spoke with Peyghamy about the history of his setup, his “patching” philosophy, and the beauty of the unexpected in live performance.

There is a track on my EP called "Sympathetic Fillings," in which I manipulate a sample of santur, a traditional Persian dulcimer. The sound of Persian instruments has always had an emotional impact on me.

I started learning tombak in 2017. Before that, I’d played the drums for 7-8 years and I wanted to try something new. One day, I stumbled across a famous video of Mohammad-Reza Mortazavi playing the tombak. I was impressed by his virtuosic technique, but also by how he could make the instrument sing in ways that were almost “electronic.” I immediately decided that I wanted to learn this instrument.

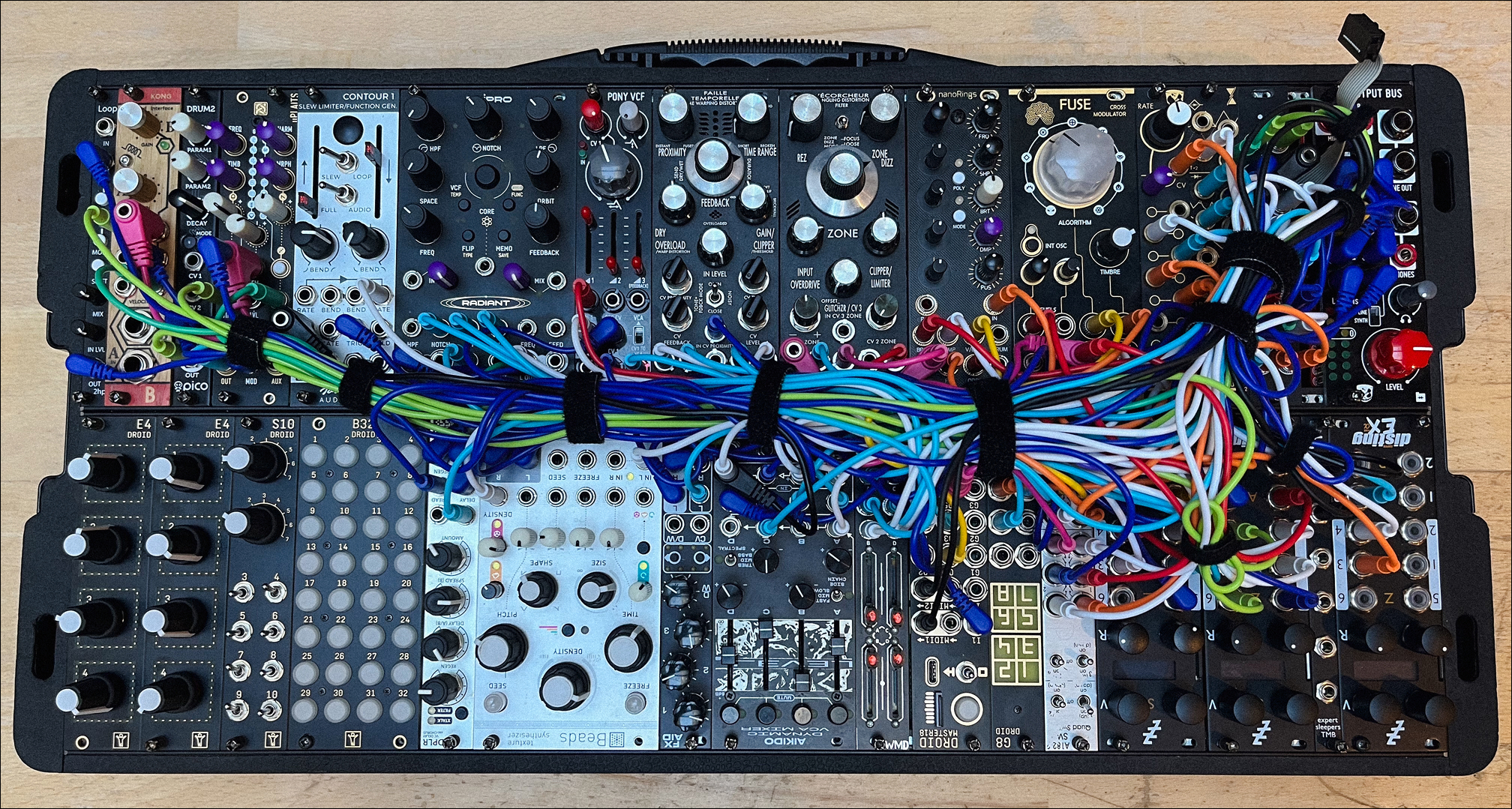

When I was watching synth videos on youtube, I would sometimes see these huge machines with wires and I was always thinking “What the hell is that? How does it work ?” I was fascinated by these machines. I realized that the only limit to a modular synth is the one fixed by your imagination. Compared to a regular synth, guitar pedal, or drum machine, all of which are fixed in their electronic design, the modular has an open architecture. This is what made me pull the trigger.

Compared to a regular synth, guitar pedal, or drum machine, all of which are fixed in their electronic design, the modular has an open architecture. This is what made me pull the trigger.

Obviously, they are both very complex instruments but in very different aspects:

My relationship with the tombak is purely physical : I hold it, I hit it, I scratch it. I practice everyday with it, I carry it around. I hurt my hands when I’m playing it too hard. My considerations are: “is my hand technique good ? Am I precise enough when I play at this specific speed? Are my fingers relaxed ?” It’s an instrument that I need to practice everyday to bring muscle memory into my hands.

With the modular, it’s more of a mental connection. I spend more time thinking about it than actually playing it: which module I should add or remove, how I would interconnect them, how I can use that free space to add complexity to my patch. It’s like doing a puzzle, or playing a strategy game. You spend more time thinking about your possibilities than doing the actual move.

My modular case is built around these 3 ideas: transforming the sound of the tombak in real-time, using the sound of the tombak to trigger musical elements from the synth, and being able to improvise a full set (45-60 min) with all the tools at my disposal. When I’m designing a patch, I’m always looking to fulfill these three ideas. I’m looking to create a symbiosis between the tombak and the synth in order to play beautiful music.

Designing a patch is really the fun of modular. In my case it’s not assimilated with composition. It resembles architecture, industrial design, or even computer programming in the sense that I’m building something that I’m going to use on a daily basis.

Once the patch is done, I leave it this way because I need to practice with it and play live with it because during my gigs, I make really instinctive decisions during my improv. Usually, I keep my patch for a year and a half (that’s about 20 shows) before trying a new one. During this time, I analyze which part of the patch works the best, which one I don’t use much, etc. It’s also a lot of research online to know which module I’m going to buy/exchange for the next iteration of the patch. When it’s time for me to unpatch and create a new one, I usually know what I’m going for and I’ve already gathered the necessary modules. Then I usually need a whole week to create the new patch, fine tune it and get used to it. Then the cycle starts again and I use my live shows to test this new patch.

[Patching] resembles architecture, industrial design, or even computer programming in the sense that I’m building something that I’m going to use on a daily basis.

When I play live I’m in a kind of hyper-focused mode in which I’m not paying any attention to what’s happening around me. There could be 10 people or 1,000—it wouldn't change anything. There is just me, the tombak, the synth, a very tight space where everything that is happening depends on the movement of my hands, fingers, and the musical decision that I make.

On top of that, I’m almost done with my debut full-length album. It’s a continuation of what I did with The Skin In Between: exploring the different possibilities that the tombak offers as a compositional tool in an electronic framework.

I can’t wait to show it to the world. Hopefully it’ll be released by the end of the year, or early 2026.

Cover photo courtesy of Bachir Tayachi