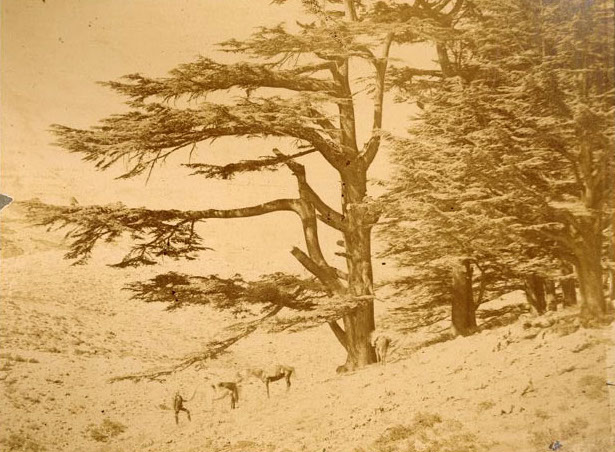

1/226, 1/227 / The E.W. Blatchford Collection / American University of Beirut

Historically, Lebanon has always been a territory where many identities coexist, shaped by different and conflicting hopes and desires. Researcher and translator Diana Khamis, who was born in Moscow and grew up in Beirut, explores the formation of Lebanese borders as well as the multiplicity of ideologies within them in this context.

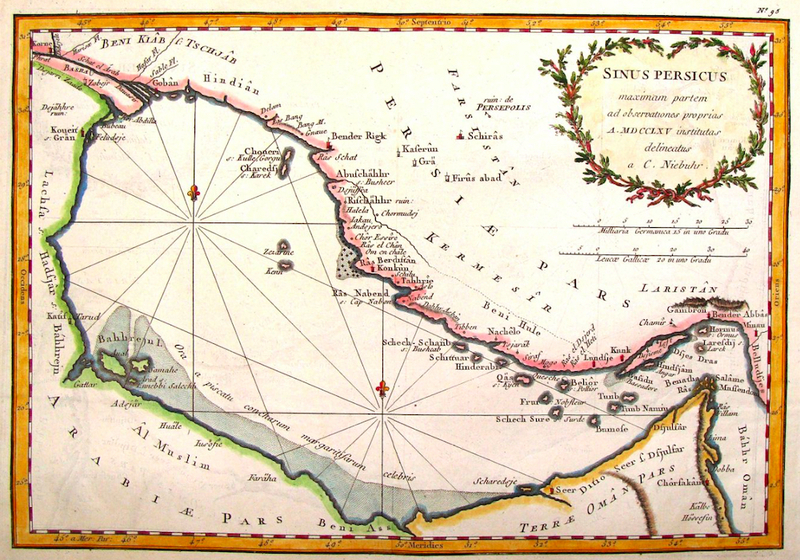

For a conventionally Western person, Lebanon is a more than conventionally Eastern country, associated with sands, terrorists, refugees, and other “standard” images of the East. Fortunately, things are not so clear in the eyes of Lebanese people themselves, partly thanks to the conventionality of the concepts of “East” and “West,” especially when it comes to the LevantLevantLevant is the common name for the countries of the eastern Mediterranean, in a narrower sense—Syria, Israel, and Lebanon. Definitions of the word vary greatly across countries and eras. and what is now called the “Middle East.” A simple example of the complexity of this conventionality in the region would be as follows: in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Ottoman Empire undertook various attempts to Westernize its political system and experienced considerable Western cultural influence, all the while unambiguously retaining, in the eyes of Europe, its status as the exotic “East.”

A more complicated example has been unfolding in Lebanon throughout its entire history. Up until the devastating civil war that engulfed the country in 1975 and lasted until 1990, the Lebanese people (at least a part of them) referred to their country as the “Switzerland of the Middle East” (emphasis on “Switzerland”), while its capital was sometimes proudly pronounced to be the “Paris of the Levant.” Their monikers referred not only to the fact that in the 1950s and 1960s Lebanon was the banking center of the Middle East and a tourist paradise, but also to the fact that a large part of the population quite honestly took themselves to be Western. Even now, newspapers occasionally carry headlines along the lines of “Could Beirut Become Paris Again?,” which has less to do with expressing a nostalgia on behalf of the Lebanese towards some conventionally Western state of being and more to do with a certain portion of the population’s desire to once again become, in their own eyes and eyes of the whole world, a part of the West: that West to which Lebanon, in their opinion, truly belongs, with flower beds, churches, Paris copycat architecture, and Francophone girls in mini-skirts, not with deserts, bombs, and pictures of martyrs who died fighting for Asad’s regime in Syria on every other house in some quartiers. But how did it come to be that in Lebanon the conventional East and the conventional West came together, just as conventionally?

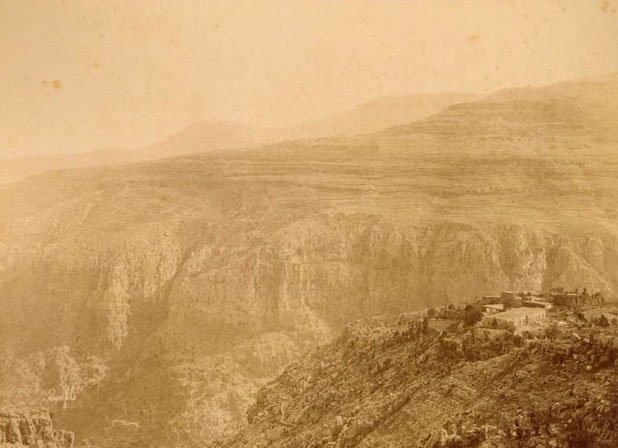

1/224, 1/229 / The E.W. Blatchford Collection / American University of Beirut

History and Borders

In order to give an answer to the above question—an incomplete and truncated answer, but an answer nonetheless—we would first need to take a historical detour which would examine the emergence of the state of Lebanon with its borders and demographic peculiarities. As a definite administrative unit, Lebanon first took shape as part of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the 15th century15th centurySee Fawwaz Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon (London: Pluto Press, 2007), 3.. Back then, this unit was a lot smaller than it is now and bore the name “Emirate of Mount Lebanon.” However, already at that time the population of the Emirate was divided across a number of religious groups: people belonging to several Christians and Muslim confessions, as well as Judaism, called the Emirate their home. The rulers of the Emirate—first DruzeDruzeThe Druze are a religious community who follow a sytem of teachings descended from Ismailite Islam. The Druze follow some Muslim doctrines, but their faith has been influenced by Hinduism and Platonism and they believe in reincarnation.

, then Christian—were eager to seek the support of European aristocrats against Turkish governors—the Emirate rose up against the Ottomans several times throughout its history. Although the Christian Emirate did not last very long, its borders later became the basis for the borders of modern Lebanon and Maronite Christians have, throughout the entirety of Lebanese history, viewed themselves as a demographic constitutive to the nation and country.

When after the First World War the victorious European powers signed the Sykes-Picot agreement, dividing the Middle East into European protectorate zones, France got the so-called “Syria”—contemporary Syria and Lebanon—as its immediate sphere of influenceinfluenceSee A History of Modern Lebanon,75.. Then, it was the head of the Maronite church Elias Hoayek who appealed to the European powers in the name of his flock (and all the Lebanese), asking to extend the borders of the existing territorial unit—Mount Lebanon. He was basing his proposal on the consequences of a terrible famine which had struck Greater Lebanon during the war, and extending the borders through the addition of coastal agricultural territories and the Bekaa valley (primarily populated by Muslims) was supposed to make Lebanon self-sufficient when it came to food productionproduction I skip over many details pertaining to the regional context of these decisions. For more detail see A History of Modern Lebanon, 75-80.

. The establishment of a French protectorate over Lebanon was also among the points proposed by Patriarch Hoayek.

The European powers accepted the proposal. Lebanese historian Fawwaz Traboulsi notes that their actions point to the various degrees of ethnicization with which Europe viewed peoples of the Middle East. Around that very same time, the Foreign Secretary of Great Britain Arthur Balfour sent his famous declaration to lord Lionel Walter Rothschild, where he officially approved the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. Traboulsi notes: Great Britain viewed Jews as a group with its own national and ethic identity, while other people of the Middle East were viewed by Europe as certain religious communities (Muslims, Christians, Druze) and not as a defined nation or set of nations, with their own political rights and aspirationsaspirationsSee A History of Modern Lebanon, 76.. They were, on the one hand, homogenized as a certain “East” or merely “non-West,” and on the other hand viewed as divided into various categories within this very label.

Be that as it may, thus—in a rather arbitrary fashion and with the blessings of France—the borders of the state of Lebanon were formed. I call these borders “rather arbitrary” because the above complex homogenization played a role in their formation: some parts of formerly Ottoman Syria were appended to the territory of Lebanon, so that some villages were literally split in two without much thought given to the consequences: at the end of the day, the Middle East was uniformly populated by some “Eastern peoples,” they had long been united by Ottoman rule, and as to their differences,well, France would, so they claimed, valiantly defend the rights of all religious minorities, as per its assurancesassurancesIbid.. In this historical key, it must be remarked that the Sykes-Picot agreement did not let France keep its promise concerning the creation of a Pan-Arab kingdom on the Arabian peninsula—a promise it gave to Faisal, the Emir of Baghdad, who strove to create such a kingdom and reduce the tensions between Shiites and Sunnites. This failure will only complicate the interconnection of “West-ness” and “East-ness” in Lebanon, leading to a prolonged ideological conflict between pan-Arabists and Westernizers, which I, among other things, will touch on in what follows.

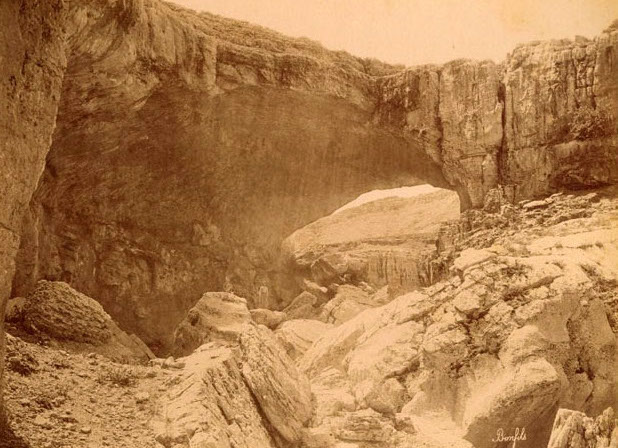

1/184, 1/186s / The E.W. Blatchford Collection / American University of Beirut

A Few Identities Too Many

The aforementioned conflict between pan-Arabists and Westernizers, as well as the subsequent division of Lebanon and its political culture into diverse, new, and numerous spheres of influence and “soft power,” are significant and sizable topics. But they are a part of an even vaster, almost boundless problematic—the problematic of Lebanese identities in the broad sense of the word. This is perhaps almost a cliche, but Lebanon is a very multifaceted and heterogeneous country. In order to demonstrate this colorful complexity without resorting to most certainly cliche statements about eighteen different confessions and about how in Lebanon “you can ski in the morning and go to the beach in the evening,” I would like to look at three cases of multifaceted Lebanese identities, weaving together “East” and “West.” I will begin with the architectural/urbanist identity of the Lebanese capital, then move on to the identities dominating political culture, and end with the linguistic identity of the Lebanese population. When examining these identities, it is important to remember that they are to a considerable extent interconnected and that the problematic of identities has numerous other aspects which I cannot touch upon here.

The City

Perhaps the most obvious way to examine the intersection and intermingling of what is conventionally Eastern and Western in Lebanon is to take a look at the identity of the Lebanese capital Beirut. In the 19th century, Beirut had all the looks of a typical “Eastern” city, the space of which was organized around markets with fountains and coffee houses. In such a communal space, the inhabitants could not only purchase foodstuffs and other goods, but also perform their ablutions before praying at a nearby mosque (this was an important function of the fountains) and kill time in a coffee house while socializing, reading newspapers, or playing backgammon. Narrow residential streets formed rays leading away from the marketplacesmarketplacesOn this see Nadine Hindi, “Narrating Beirut Public Spaces Westernization: An Urban Perspective from the Late 19th Century” in Mediterannée, 131/2020. .

Despite the fact that the French mandate was officially enacted in Lebanon after the end of the First World War, French forces had already entered Ottoman Beirut in 1860, after a civil war in the Emirate of Mount LebanonMount LebanonThe Ottoman Empire, against which the Emirate of Mount Lebanon rose up in the XIX century as well, permitted a contingent of 12000 European soldiers to arrive in Lebanon.. The French presence had already begun to influence the city by then, and this was only helped by the Ottoman desire to modernize and Westernize its cities by, for instance, connecting them with railroads, instituting postal and telegraph services, and founding public health and sanitation services. In Beirut, the presence of French troops and French medics played a role, among other factors: they pushed Ottoman city-planning officials to begin expanding the streets, closing the markets to “improve sanitation” and, allegedly, ventilation, on the narrow streets of the city. The French mandate continued with this tendency: streets became wider and straighter, markets and even simple squares where civic interaction could take place practically vanished. In essence, from the point of view of urbanism, the “Eastern” character of Beirut was barely retained, especially in comparison with such historical cities as Lebanese Saida or Damascus before the war, where markets with branching narrow streets were preserved. Nevertheless, houses in the Westernizing Beirut, already transforming into a “Paris of the Levant,” were still built in a conventionally Eastern style, with the large, easily recognizable sets of three windows under a triple arch and a large central room. Now, however, these houses were increasingly built with several stories, accepting Western influence and shaping modern Lebanese architecturearchitectureSee Robert Saliba, “The Genesis of Modern Architecture in Beirut, 1840-1940” in Architecture Re-introduced: New Projects in Societies in Change, edited by Jamal Abed (Geneva: The Aga Khan Award for Architecture, 2004). Also accessible from Archnet.

.

After the civil war, a similar “forced Westernization” repeated itself, but under completely different circumstances and for different reasons. Businessman and politician Rafic Hariri created the Solidere stock company, which was granted expropriation rights by the government and was able to purchase land from its owners in order to “restore” the city center. The center was restored—in an even more Westernized East-Western style, now with high-rise buildings constructed as offices, too expensive for the average inhabitant, luxury hotels, restaurants, and European fashion house boutiques. The Lebanese people understood rather quickly: the “pretty” downtown area was not built for them, and it never really fully came to life. Now, after many terrorist attacks, after anti-corruption demonstrations, after the August 4th explosion in the Beirut port, some roads in and around the downtown area are closed, protected by armed forces, but even before these events the center of Beirut looked more like a pretty veneer, the model of that coalescence of East and West which Lebanon has attained—or merely thought to attain.

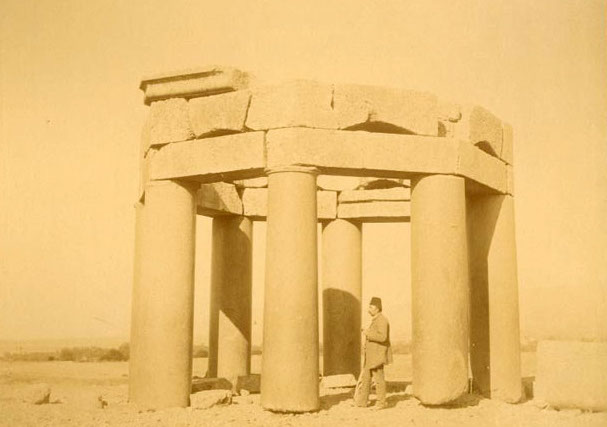

1/201s / The E.W. Blatchford Collection / American University of Beirut; 1982.1153.15, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Political Culture

When the richness of Lebanese culture and the plurality of its identities is brought up, many inhabitants think of political culture and the connections between their largely economically and politically dependent country with foreign powers. The minuscule size and considerable cultural diversity of Lebanon has led to a perhaps perfectly foreseeable consequence: from the very moment of its founding, various groups have directed their gazes outward to form various kinds of alliances. Bearing in mind the initial French promise to help found a Pan-Arab state on the Arabian Peninsula, some Lebanese groups had high hopes for the regime of Gamal Abdel Nasser (in the 1950s his program was supported by some Muslim leaders and the Druze-founded Progressive Socialist Party) and for a unification with Syria (in the 1960s, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, also operating in Lebanon, supported this ideaideaRobert G. Rabil, “The Confessional System Between Lebanonism and Pan-Arabism” in Religion, National Identity, and Confessional Politics in Lebanon (London: 2011), 17-29.). These hopes, however, have flared up at times and were extinguished at others, as the geopolitical distributions of power shifted and various ideological and confessional groups in Lebanon balanced for the sake of political survival or sometimes just survival tout court.

Maronite Christians, taking themselves to be a founding Lebanese demographic, took such ideas to be a betrayal of Lebanon’s exceptional “West-ness” in the Middle East—the Lebanese people, according to them, are Phoenicians, Lebanon is a refuge for religious and ethnic minorities, and Pan-Arabism is merely an ideological illusion that would doom the unique identity of Lebanon to ruin, and hence a threat. In order to protect the potentially oppressed “Phoenician” identity and resist Pan-Arabism, according to this group, the cultural and geopolitical connections with European cultures are to be strengthened and Lebanon is to become a kind of “special zone,” a bridge between East and West, not quite European, but certainly not Arab. All in all, this egregious disunity and tension when it comes to the internal and external orientation which the country should adhere to in the opinions of various political players, along with the onset of economic problems and the general backdrop of regional political conflicts, finally led to civil war, which undermined Lebanon’s independence even further. To secure an end of the war, Syria intervened directly in the conflict, sending its troops into Lebanon and making the interference of other countries all the more desirable and expected for these countries and some parties in Lebanon. In light of these developments, Shiite Muslims, as a once persecuted minority seeking guarantees for their own survival and prosperity, have also formed their own dangerous liaison—with Iran, the country of the Shiite majority.

Since then, the pie called “Lebanon” has been cut up with even more fervor, while its geopolitical and economic dependence has become almost catastrophic—certain roles in it are allocated to Europe, Russia, Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Gulf states, as well as, obviously, to the USA. Many of these countries offer financial aid to Lebanon, which largely translates into financing the corruption of the present regime. Lebanon’s political system is perfectly conducive to that—in essence, it is based on quasi-feudal clans, holding power for generations and misusing the country’s finances along with their political allies. While pocketing aid from one or another country, the Lebanese political elites campaign for one or another political orientation, so that “East” and “West” cease to be at least somewhat definite categories or direction, but become utilitarian situational labels, dependent on geopolitics.

Below: Félix Bonfils studio. View of the Maronite Catholic Church monasteries in the Kadisha Valley. Nabaa el Labane spring. Lebanon, 19th century

LSH 104293, Hallwyl Museum; 1/231, 1/232 / The E.W. Blatchford Collection / American University of Beirut

Language

Even when it comes to the language used by the inhabitants of Lebanon in their daily life, Lebanon demonstrates a mix of the conventionally Western and conventionally Eastern. The Arab world is diglossic. Classical Arabic—the language used to compose the Koran—was, for religious reasons, prescriptively preserved, undergoing very limited changes since the 7th century and becoming Modern Standard Arabic (the language of most literature, the news, and official forms). Alongside this literary language, only used for writing, there is a multitude of dialects which people use for daily communication. Thus, the language which a Lebanese person learns to speak as a child is not Modern Standard Arabic, but a special Lebanese dialect (with regional variations). Because of this, Lebanese people who take themselves to be “Phoenician” claim that this very dialect is not a dialect of Arabic but a separate language, descended from Neoaramaic, pointing to certain loan words from Aramaic. These are usually very simple everyday words (such as “bayt,” “zalameh,” “mara”—house, man, woman). At least some of these etymological derivations are questionable, but such essentialist ideas are entertained even by well-known and respected Lebanese people, such as Nassim Taleb, author of “The Black Swan” and zealous proponent of Lebanese exclusivity.

To better understand the state of languages in Lebanon, it is perhaps even more important to note that in the second part of the 19th century, Protestant missionaries from the USA and Jesuits from France founded Lebanon’s two oldest and best universities, with education in these universities being conducted, up to this day, in English and French respectively. Regarding school education, Lebanon follows the French baccalauréat—an international system where the first foreign language is given considerable attention. In the Lebanese version of this system, exact and natural sciences are taught exclusively in a foreign language and the humanities (barring the foreign language itself)—exclusively in Arabic. In a country where the job market has opportunities only for people educated in technical and scientific fields, this leads to a disproportionate importance of the foreign language at the expense of the native one. This importance has led to the fact that, in educated circles, French (which has long been taught at schools at a rather high level) and English (more recently) have become, to some Lebanese people, practically native languages—those in which these people are most comfortable speaking. The divergence between the spoken and the written language lead, literally, to a poor command of Arabic and to the fact that many people end up “living” in a foreign language. Class differences play a role here, but not always and not everywhere—of course, expensive and prestigious private schools are going to be better at teaching foreign languages initially, but this is changing with time: even in remote villages there are more and more people who speak a foreign language at least decently, while having some difficulty expressing themselves in literary Arabic. The Western languages have practically become the Lebanese person’s own.

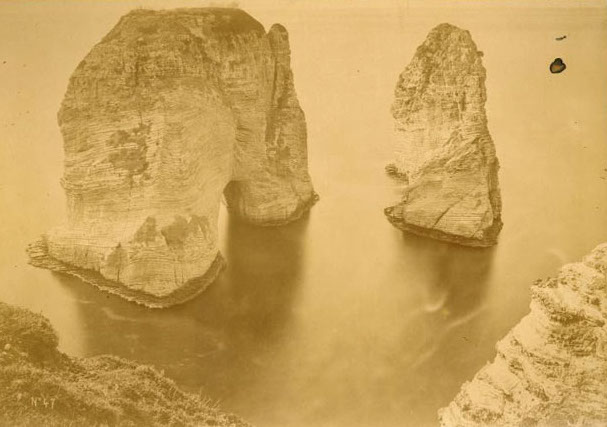

Right: Unknown author. The Pigeons' Rock in Beirut. Lebanon, 19th century

1/182, 1/190 / The E.W. Blatchford Collection / American University of Beirut

Non-existing Phoenicians, Nobody’s Emirate

From the elements of Lebanese life examined in this text, from their West-ness and East-ness, perhaps only one thing follows: Lebanese identities are very fluid and manifold, both due to the initial coexistence of many identities in a small territory and for geopolitical reasons. To clarify this further, it would be good to give more concrete examples. The Pan-Arab state towards which some political groups claim to strive should, for some of them, be secular and socialist (or national-socialist) and for some others—an Islamic Ummah or Caliphate. A more “individual” example would be immigration—due to the giant size of the Lebanese diaspora, the members of which come back to Lebanon temporarily or for good from time to time, Lebanon has many individuals with a complex identity that is “switched on” in different moments. Among people I know, there are many Lebanese people whose families have often lived abroad and returned to Lebanon, but also Palestinians and Armenians who have grown up in Lebanon, but also lived in the USA or in Europe for many years. Various elements of these people’s identities are performed by them at different times—they can be anti-Zionism activists or be spreading awareness about the Armenian genocide, they can genuinely support civil society in Lebanon because they feel Lebanon is their home, genuinely doubt and even deny that Lebanon is their home (perhaps for being othered by their Lebanese countrymen), have a certain look or hobby (put on a specific kind of dress, practice traditional crafts or perhaps “Western hobbies” such as rugby or flamenco.

People who have certain cultural connections to various cultures around the world and communities within Lebanon (and people like these are numerous) also have, each one of them, several positions from which they evaluate events around them. They view things simultaneously—or not quite: as a daughter of refugees, loyal to the Palestinian cause and as a talented literature scholar, forced to study Arabic literature in the West, not always sure how to combine the customs of “home” with Western life. They can be an Armenian who loves Lebanon but tries to emigrate to Armenia, because Lebanon is still somehow foreign, despite all their attempts to help build a civil society in a country that is not quite theirs. They can be a chemist who studied and worked in the US, nevertheless believing in a Pan-Arab state and condemning US foreign policy.

Furthermore, the second and third generation of immigrants from the Lebanese diaspora end up growing up in the West, although many of them strive to marry Lebanese people and raise “Lebanese” children—but the results are not as equivocal: if young people from these “new generations” end up in Lebanon, they experience, ultimately, a considerable gap between their life choices and their environment, which they then later come to influence. To give a more concrete example: if you visit private Lebanese universities, you are likely to feel the influence of feminist and LGBT activism. There are activist lectures, discussions, protests. The influence of “Western” stances on gender is felt as something clearly attributable to its Western origins, but not necessarily as something foreign, as people who bring these stances to Lebanese discussion spaces most loudly are themselves Lebanese. Thus the involvement of many Lebanese people in the complicated nets of “East” and “West” complicates the use of these categories, blurring the lines between them and depriving them of that dubious usefulness which they had initially. But despite all of the above, Lebanon always remains “Eastern” in the eyes of the “West,” and all those complex Western and West-leaning aspirations, legacies, and dependencies become, in the best case scenario, the source of a rich, special identity, and in the worst—an illusion leading to discrimination and arrogance for being utterly exceptional.