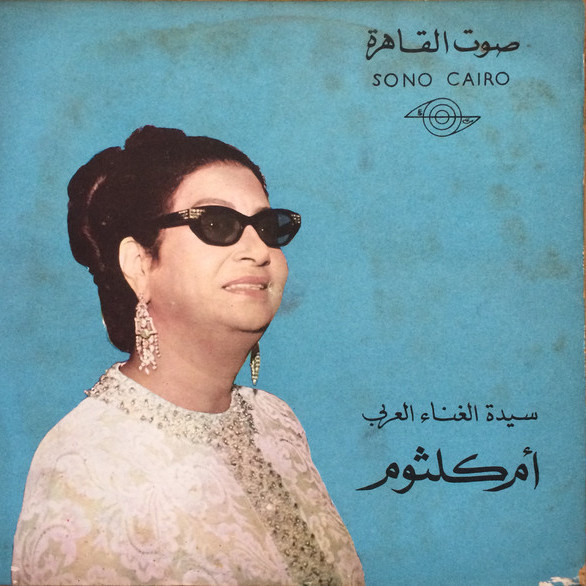

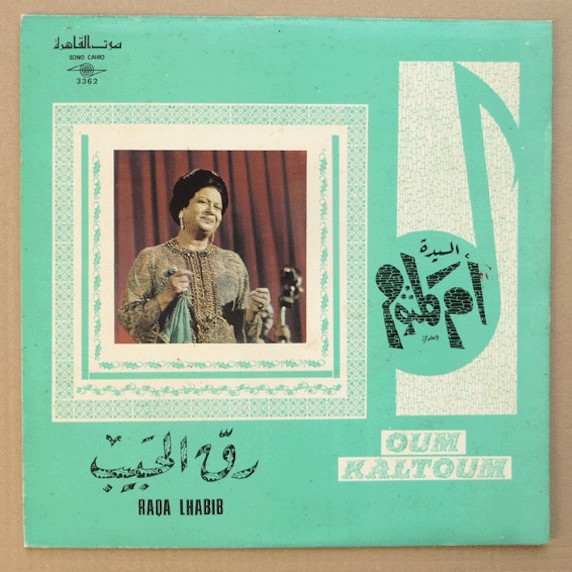

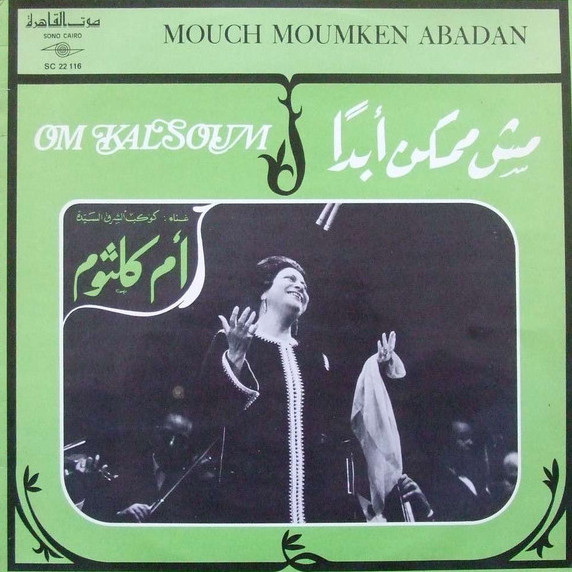

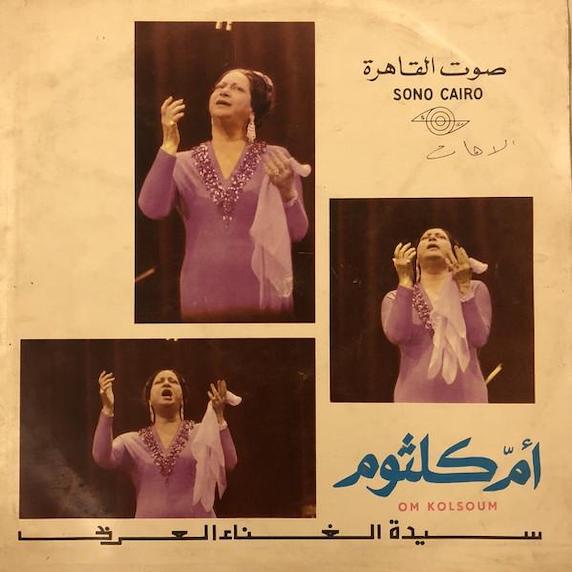

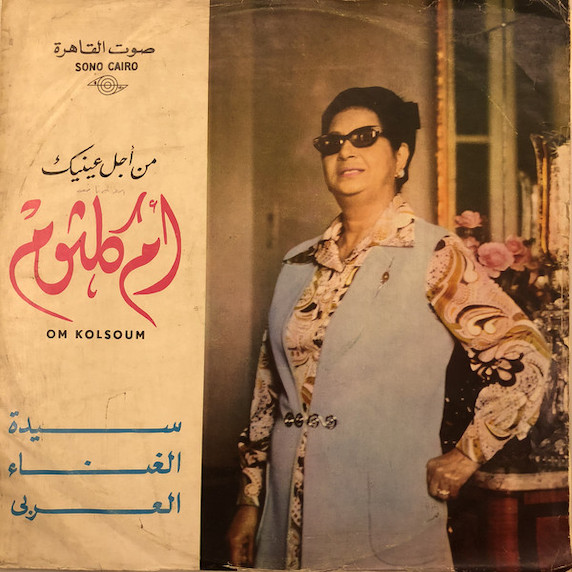

discogs.com

While the name Umm Kulthum is familiar to many, it takes more to fully appreciate the myriad of meanings and cultural resonances that her life and music represent for both Egyptians and others across the Arab world. Ethnomusicologist Lillie Gordon, who in her work focuses on the adoption and adaptation of the violin in Egyptian music, presents a more holistic picture of this iconic musician's legacy, drawing from specific performances, song lyrics, film roles, and her own discussions with Egyptian musicians who played in Kulthum's ensembles.

Collective and Individual

“Al-Atlal” is primarily a melancholic love song, as are so many classic Egyptian songs. As an individual, you empathize with the protagonist, singing amongst “The Ruins” of a past love. You listen in wonder and perhaps respond with your own voice as the singer, with extreme sensitivity and dexterity, guides you from a longing that “burns your ribs” to blissful reminiscences about walking along “moonlit paths” with your lover. And yet, in the same song, everyone’s love story becomes about more than romance. The lover pleads, “Give me my freedom, unchain my hands.” More than fifty years later, people across borders use these lines to plead with unjust governments and gather support. The meanings of the words echo through the everyday and extraordinary moments of people’s lives.

It’s rare to find an artist like this singer, Umm Kulthum. Her music stands as an example among the highest artistic achievements in Egyptian (and Arab) music history, and yet you find people humming her songs in line at the grocery store and blasting them over loudspeakers at weddings. Throughout her fifty-year career and in the decades since, she has become the most recognized voice in Egypt and perhaps across the Arab World. While her story and music are surely exceptional, they feel like everyone’s story, and recount a collective history in the process.

A Timely Collection of Aesthetics

Throughout her career, Umm Kulthum offered a unique blend of aesthetics and imagery that skillfully matched (sometimes purposefully) the desires of the changing times. She was born in a rural village in the rich agricultural Nile Delta region at the turn of the 20th century (c.1898-1904). Her father, Shaykh Ibrahim, led the local mosque, and sang at local religious holidays and family occasions. As a child, Umm Kulthum’s local school taught her to memorize, read, write, and recite the Qur’an, skills that critics later referenced when explaining her fine diction. Even as an adult, after Umm Kulthum had adopted many en vogue cosmopolitan aesthetics, her rural, working-class, and religious upbringing would appeal to fans and politicians seeking a “salt of the earth” and uniquely Egyptian cultural representative.

Initially hesitant about permitting his daughter to perform publicly out of concern for her reputation as a woman, Shaykh Ibrahim eventually began to include Umm Kulthum in the family group of singers. Supposedly, her father had her dress as a boy at first, more to mediate his own discomfort with her inclusion in the band than to fool any audience members. With the family group, Umm Kulthum performed religious repertoire all around the region, sometimes in the homes of local gentry with far-reaching connections. Her reputation as a singer grew quickly as the family traveled far and wide to perform, often by train, which in turn allowed her to increase her fee and support her family.

Encouraged by several well-connected patrons, Umm Kulthum’s family moved to Cairo in the early 1920s. At that time, a wave of urban migration in Egypt saw thousands of families relocate from rural areas to Cairo, Egypt’s industrial, commercial, and media center. There, Umm Kulthum began to perform with a small instrumental ensemble (takht) for the first time, giving her a decidedly urban sound. Her takht consisted of some of Egypt’s finest instrumentalists, including violinist Sami al-Shawwa and ‘ud player and composer Muhammad al-Qasabji. They staged (newly emergent) public concerts, with (sometimes rowdy) audiences populated by Egyptians, Europeans, and members of the Ottoman elite. Following the fashion of the time, she also began to perform secular songs, some of which clashed with her country girl persona. Ultimately shedding that image, Umm Kulthum embraced new technologies and fashions while maintaining a level of modesty not prioritized by other women performing at the time.

discogs.com

Umm Kulthum made her first audio recordings in the early 1920s, but according to biographer and ethnomusicologist Virginia Danielson,Virginia Danielson,Virginia Danielson, The Voice of Egypt: Umm Kulthūm, Arabic Song, and Egyptian Society in the Twentieth Century. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997) her 1927 recordings are what really launched her career. Songs like “In Kunt ‘Asamih” met the mood of the time by combining classical artistry, modern aesthetics, and Romantic poetry. Since moving to Cairo, Umm Kulthum had studied with famed teacher al-Shaykh Abu-l-‘Ila Muhammad. Though she was already accomplished, Shaykh Abu-l-‘Ila enhanced her knowledge of the Arabic classical repertoire of melodies and poetry, the mechanics of vocal control, and most importantly, how to marry the meaning of lyrics with her vocal executionvocal executionIbid 56-57

. At the same time, Muhammad al-Qasabji’s composition combined an emphasis on thirds and large melodic leaps, heard as European at the time, with movement typical of the Arab maqam (modal) systemthe Arab maqam (modal) system The system of melodic modes used in traditional Arabic music. Each maqam is built on a scale, and carries a tradition that defines its habitual phrases, important notes, melodic development, and modulation. The word maqam in Arabic means place, location, or position.

. Finally, Ahmed Rami’s poetry melded syntax akin to Romantic poetry with imagery common in Arabic songs. Umm Kulthum combined these elements with her vocal delivery, including the careful use of hoarseness and wide vocal vibratovibratoA musical effect consisting of a regular, pulsating change of pitch used to add expression to vocal and instrumental music.

, to create a blend that was heard as modern, classical, and grounded. Though her early repertoire has not remained her most well-known, it captured the multidimensional moment in which it emerged.

Repetition, Replication, and Reimaging

In addition to recordings, Umm Kulthum’s fame emerged as a result of her embrace of other new media, namely radio and film. After she signed on in 1934, Egyptian (national) Radio began broadcasting Umm Kulthum’s songs and eventually her live performances on the first Thursday of every month. With Thursday night marking the beginning of the weekend in majority Muslim countries like Egypt, these broadcasts took on the tone of national events. Cairenes recall that the usually raucous and noisy streets of Cairo would become unusually quiet on those Thursday evenings, as most people crowded around their radios or those that were broadcasting in public places, including Cairo’s thousands of cafés. These concerts established Umm Kulthum as a national fixture, part of everyone’s monthly routine, rhythm, and rituals.

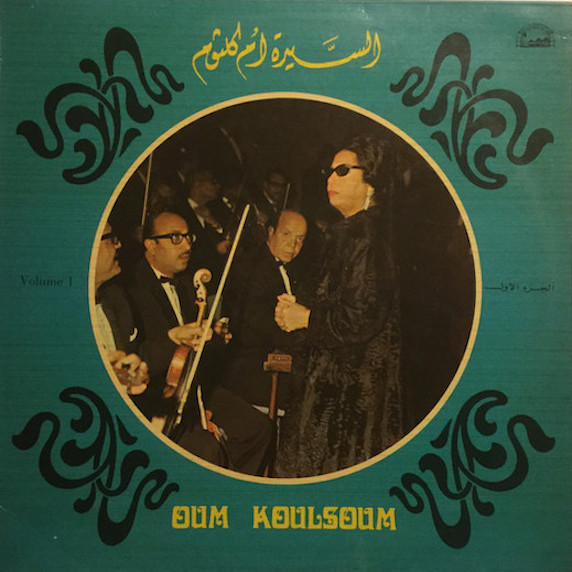

Umm Kulthum prepared at length for these events and indeed for all of her performances. One of my own violin teachers, Sa‘d Muhammad Hassan, played in her ensemble for the last years of her career. In his experience, Umm Kulthum insisted that the whole band learn all of her very long, multi-part songs by ear. He recalled sitting in rehearsals for many hours, not only learning each musical line by ear from the composer himself, but also committing the words of the song to memory. By the 1950s, many professional groups relied on sheet music to acquire repertoire quickly, but that was not the practice in Umm Kulthum’s ensemble.

discogs.com

She also embraced film, starring in six features in the 1930s and 40s. Many people characterize those years as Egypt’s golden age of cinema, and as the media center of the Arab world at the time, Egyptian films appeared on screens far beyond Egypt’s borders. Her films, like her songs, presented a combination of aesthetics considered to be modern and those heard as traditional. While half were period pieces, the others captured the class and sociocultural tensions of the present. In the film Fatma (1947), Umm Kulthum plays a nurse seduced by the brother of a wealthy patient. He marries her but then later rejects her out of distaste for the working-class neighborhood and people amongst whom she is a beloved fixture. In the end, her neighbors help her to bring a suit against the wrongdoer. The movie contrasts the virtuosity and loyalty of the working class with the lasciviousness and corrupt behavior of the wealthy, foreshadowing Egypt’s revolution that would come just five years later.

In her films, Umm Kulthum would primarily perform short songs with varied sections. These contrasted dramatically with her performances, in which she became known for elongating songs through repetitions and variations. By the 1940s, she was specializing in a long song format often called ughniyya, a multipart composition involving contrasting instrumental and vocal sections, with the original compositions’ only repeated material coming in the last few phrases of the vocal sections. “Al-Atlal,” mentioned above, is a good example of this type of piece. Umm Kulthum would also use her short film songs as the basis of these long performance versions, sometimes stretching an originally five-minute song out for an hour.

Take the song “Ghannili Shwayya, Shwayya” (“Sing to me a little bit”), which originally appeared in the film Sallama (1945). The film version is almost over before it begins, as country girl Sallama jovially enchants us before the story really gets going. Though short, there is complexity here; some of the stanzas modulate away from the original mode (maqam) and then return back again, for example. The chorus of the song is also supremely memorable and singable. Most Egyptians can still sing the chorus of this song.

In a concert version of this same song, which this Youtube member claims was recorded on December 4, 1952, the film version becomes a skeleton for Umm Kulthum’s unique artistry. Lines that took a few seconds in the film expand into chances for everything from slight phrasing variations to spontaneous modulations. The now large ensemble (firqa) and chorus can be heard repeating ostinatos ostinatos A repeating phrase or motif. in the purposefully “messy” heterophonic heterophonic The simultaneous performances of variations of a single melodic line.

texture characteristic of the music, as they wait for and sometimes inspire her next adventurous choice in the moment of performance. In this long section (4:45-8:55), she takes just a few short lines of text and works with them for more than four minutes. At first, she mimics what happens in the short version. Then, alternating with the chorus, she ventures further and further afield, eventually abandoning even the composed rhythmic pattern of this section for a few moments, before seamlessly bringing it back in again. Using ornamentationornamentationMusical flourishes such as added notes or movements that are not essential to the overall line of the melody (or harmony), but serve instead to decorate or “ornament” that line and provide added interest and variety.

, modulation, timbral variations, and the slicing and splicing of phrases, she makes the composition her own, bringing out and enhancing the meaning of the words. On my list of live concerts I regret never getting to see in person, Umm Kulthum’s are at the very top.

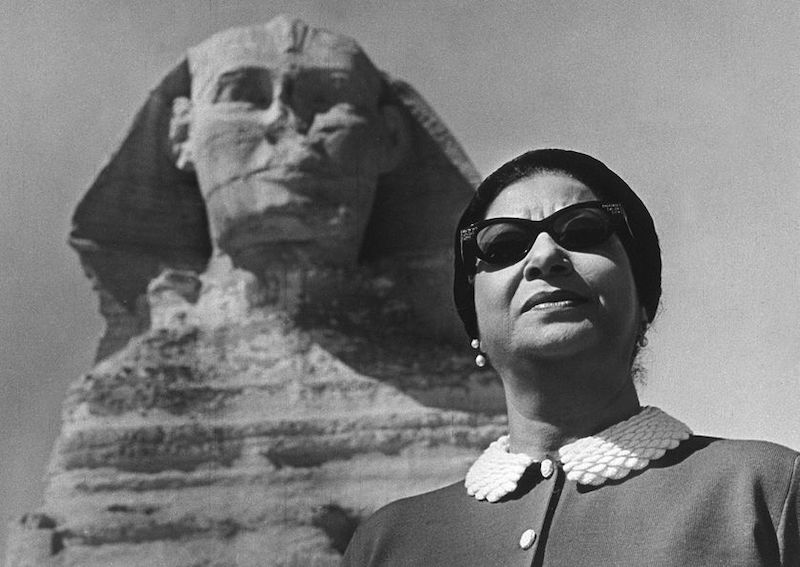

Umm Kulthum’s place as a symbol of new Egypt also relates to her connection to the changing political landscape there. She was acquainted with and decorated by King Farouk I in her early years. However, despite some backlash, President Gamal Abdel Nasser chose to harness the people’s love for the star and promoted her heavily on state radio after the 1952 revolution. Many Egyptians saw parallels between the two figures, both having emerged from rural, working class backgrounds to become emblems of modern (but grounded) Egypt.

According to scholar Laura LohmanLaura LohmanLaura Lohman, Umm Kulthūm: Artistic Agency and the Shaping of an Arab Legend, 1967-2007. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2010) , Umm Kulthum began purposefully fashioning herself as a patriot starting in the 1950s. She performed “Concerts for Egypt” throughout the Middle East and Europe following Egypt’s defeat in the 1967 war, raising money for the government itself. Now an international superstar, she promoted Nasser’s Pan-Arabist agenda and also undertook a number of humanitarian projects. Along with the abundant creativity in her performances themselves, she took specific non-musical steps to shape her public image in particular ways.

Tarab – Ecstasy

Umm Kulthum perhaps stands out most for capturing what was historically the aesthetic goal of Arab art music: tarab. Tarab is a difficult word to translate, imperfectly captured by “enchantment” or “ecstasy.” Put differently, it describes the feeling of being wrapped up in the emotional content of a work of art, most often of music. Indeed, singers are often referred to as mutrib/mutriba, a word from the same Arabic root as tarab. As is so beautifully captured and explained in Michal Goldman’s documentary, Umm Kulthum: A Voice Like Egypt (1996), Umm Kulthum brought together all of her influences, aesthetic choices, and practiced skills to usher in feelings of tarab extremely well. Attending Umm Kulthum’s performances and listening to her recordings carries audiences deeply into their feelings, opening space to relish the act of sitting in melancholy and emotional conflict.

“Ana Fi Intizarak” (“I’m Waiting for You”) beautifully captures Umm Kulthum’s virtuosity at producing tarab, something Danielson points out in her work as well. The words are arresting on their own, beginning this way:

I’m waiting for you.

With fire in my ribs,

I placed my hand on my cheek,

And counted the seconds of your absence,

And you didn’t come.

I wish, I wish, I wish . . .

I wish in my life that I’d never loved at all.

As usual, Umm Kulthum emphasizes certain words and phrases (like “you didn’t come”) by heightening the intensity of her vocal delivery through volume and attack. Most notably, she zeroes in on phrases to repeat, singing them over and over, and imbuing them with slightly different moods on each return. The next line after those above states, “I want to know if you’re angry, or if your heart is preoccupied with someone else.” Umm Kulthum works these lines for many minutes and returns to them many times (5:10-6:20, 6:39-7:13, and 8:29-10:55). Within these sections, she ornaments different syllables, elongates different words with melismatic melismatic An expressive vocal phrase or passage consisting of several notes sung to one syllable.improvisations, explores maqam-appropriate movements, and divides phrases. She settles and concentrates on different words and phrases, including “angry,” “someone,” or most strikingly, “I want to know.” A listener can meditate on this single line of text along with Umm Kulthum, ruminating on our own unrequited love stories and recognizing all the tangents she assigns those thoughts. Tarab is not just heightened emotion, but an exploration of the colors of its complexity. Her virtuosity in bringing that complexity out into the air and into our ears remains one of Umm Kulthum’s most lasting influences and achievements.

Her Legacy

More than forty years after her death in 1975, Umm Kulthum remains a central fixture in Egypt, throughout the Arab World, and beyond. Some radio stations in Egypt still broadcast one of her long songs at specific hours of the day. Those broadcasts beam into neighborhoods at some of Cairo’s ubiquitous cafés, where many people spend their evenings. Her music is performed on televised singing competitions, by religious performance groups, and by the Arab world’s top singers, including Nancy Ajram among many others. A hologram of the artist has even featured a number of times on Egyptian television. If someone in Egypt asks you, “What does ‘the lady’ say?”, you have been challenged to come up with a line from an Umm Kulthum song that fits your present situation.

Umm Kulthum’s music is many things. It’s “a school,” studied in the Arab world’s most renowned Arab music academies. Her music is a party, as her songs are intermixed with contemporary popular songs at weddings across social classes. Sometimes, her music helps make a people’s revolution. Finally, her songs are works of art: innovative, beautiful, universally known, and intimately beloved.