Canary Records is a label devoted to ethnography, collecting, and storytelling. Its owner and sole member, Ian Nagoski, researches and reissues the archival music of American immigrant diasporas. Ored Recordings founder Bulat Khalilov spoke with Ian about tradition, honesty, and immigrant influence on American culture. This article is the start of a new series of publications from Khalilov’s project Global Zomia, dedicated to DIY-ethnography and non-academic initiatives working with traditional and local music around the world.

I’m doing it because so few others are and especially that there is no one else with my particular view of the world, of being a person—that’s the shorter answer.

These records have taught me a great deal, particularly how to get rid of the element of exoticization.

The music of immigrants was profoundly influential to the music of the United States through all of the 19th and 20th centuries. Were there more popular dances from 1800 to 1950 than the polka and the waltz?

?

A true answer to your question would include a summary of the various immigration waves to the U.S. It's mostly happened behind-the-scenes. The U.S. demanded immediate assimilation from immigrants for the past 150 years, so the influences are often subtle, albeit aplenty.

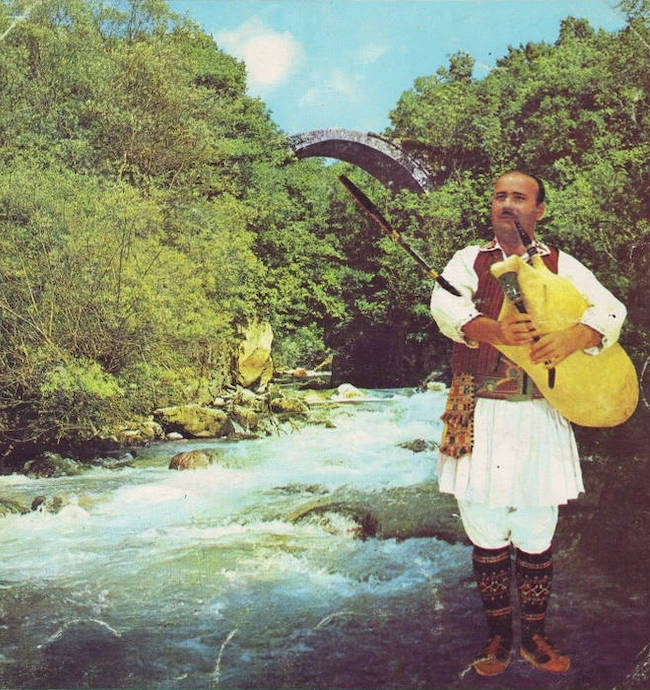

Left: To Drive Away the Vampires. Balkan Folk Musics, 1930s-80s

Right: An Unseen Cloud. Commercial American Indian Recordings of the late-40s to mid-50s

Canary Records

I don't have a particular horse in any race, ethnically speaking. Like many Americans, I am dimly cognizant of my own ethnic derivation and it means very little to me. Someone will say, “you have to hear this singer,” who may be from somewhere else. Or I will discover that a colleague listens to something I haven’t heard, and I will ask to listen, too.

About twenty years ago, I worked at a software company where half the programmers were Russian. They invited me along to a Russian bard concert. I had a memorable and pleasant time, although I did not understand a word. Similarly, I grew up in the highest-density Hindu population part of the U.S. and was lucky enough to hear some great Indian performers when I was young. Recently I was taken along to a community performance by some Pontic Greeks…

folk of the western states in the late 19th century. I know that Danish music is full of deep poetic sense, but it hasn't particularly impressed me or I don’t know it well enough. I was told that my Danish grandfather, who I’ve seen in my childhood really loved the songs of Jimmy RogersJimmy RogersA popular American singer and musician from the late 1920s who is often considered the “father of country music.”

, as I do, and was also playing guitar and singing. The other half on my mother’s side is Anglo. Protestants all around.

My father’s side is a combination of Irish and Prussian Slavs—both Catholics with spectacular musical traditions, well-documented on early 20th century U.S. recordings. So I have some connections to ethnicity and the 19th century waves of immigration to the U.S., but they aren’t especially important to my identity or daily life, and none of it was passed to me “traditionally.”

To answer your question, though, there are both benefits and barriers that result from my status as an outsider to the ethnic groups that I mainly study. People are generally kind and helpful to me. However, I know that they are often working on their own narratives of their musical/cultural/social histories, and my work is sometimes relevant and sometimes irrelevant to those projects. Sometimes I'm liked for what I’m doing and sometimes I’m seen as a pest. I've never faced any serious problems, just mild disapproval from people who think I don't know what I'm talking about—which is true in a very real way. But I'm speaking respectfully and compassionately from my own perspective, and I'm earnestly trying to educate myself.

American immigrants have always been under profound pressure to assimilate. That’s what the melting pot is, really: giving up your language and culture and becoming capital-A American as fast as possible. The melting pot is conformism

I don’t know. It’s very complicated.

American immigrants have always been under profound pressure to assimilate. That’s what the melting pot is, really: giving up your language and culture and becoming capital-A American as fast as possible. The melting pot is conformism. It generally takes a generation or two. Danish, for instance, was forbidden in the household where my grandmother grew up in the 1930s, even though both of her parents spoke it.

The cross-pollination of cultures happened largely by accident or circumstance. The velocity of global communication will be more important to the changes in American culture than, for instance, waves of Asian or African immigrants in the past fifty years. And food, because it is a more persistent and universal desire than music, will have more of an influence in cross-pollinating America than music will in the next fifty years.

America is ethnically very complicated. I haven’t even mentioned the legacy of slavery and the added layer of complexity as a result of the differentiations and inter-mixings of the cultures of black folks and white folks, which is central to the ideas of an “us” and a “them” internally in the U.S. But it would be hard to overstate the significance of that issue to a big picture of American culture and identity.

Top left: Zabelle Panosian. I Am Servant of Your Voice, March 1917 – June 1918

Top right: Hata Unacheza. Sub-Saharan Acoustic Guitar & String Music, ca. 1960s

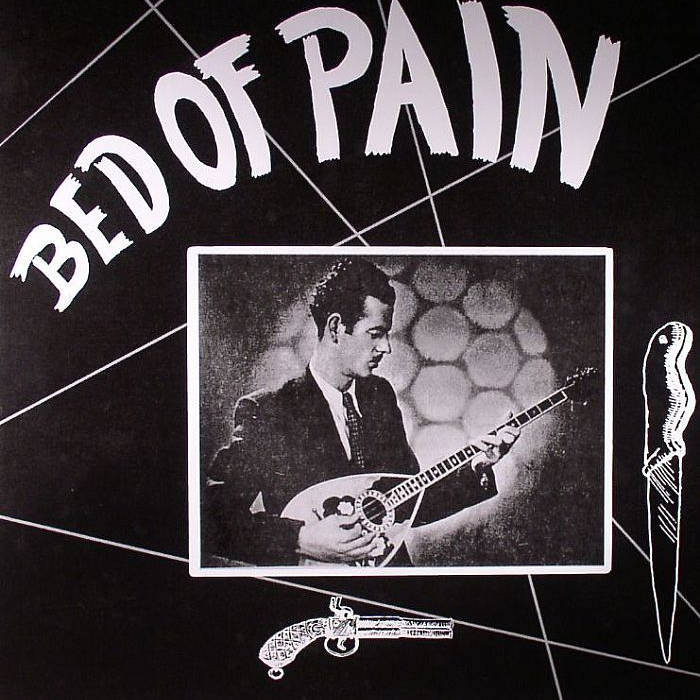

Bottom left: Bed of Pain. Rebetika, 1930-55

Bottom right: Love is a One-Way Traffic. Groovy East Asian Chicks, 1960s-70s

Canary Records

I have only been active in reissuing material for ten years and only the past five of those years have been really serious. I expect it’ll be another twenty years before my work assimilates into the public consciousness, which is why I have to do the best job I can. So that when someone really looks closely, they'll see that despite certain mistakes, the foundation of my work was built out of something real.

.

The rights owners often forget about the material. The largest U.S. record companies of the early 20th centuries don't care the slightest about some Greek immigrant singer from the 1920s. I mostly fly below the radar. The proliferation of material online has made the laws terribly old hat and irrelevant. So I don’t worry.

I have reissued songs from a record company that still exists or by an artist who is still alive, but I try to do the right thing and ask permission and send them a nominal sum of $100 or $150. I have no desire to steal anyone’s work. I try to be careful. As Bob Dylan once said: “To live outside the law, you must be honest.”

commissioned two arrangements of songs that I was the first to reissue. I’m happy about that. Anything to keep the music and the memories of the musicians alive in people’s minds.

One of my favorite singers—an Armenian immigrant named Zabelle PanosianZabelle PanosianArmenian singer, who migrated to the USA in the end of XIX century and later recorded there a series of songs in Armenian, popular in the diaspora.—wrote a song in the 1920s about her meeting with the great composer and ethnomusicologist Komitas VardapetKomitas VardapetLegendary Armenian composer, who started an extensive work of the conservation of the Armenian musical legacy. Thanks to him those traditions were not lost.

in a psych ward. She worshipped him and sang his songs, but was only given the chance to ask one question in that meeting. Her question was: “Is it okay to sing your songs that were composed for choir as solo performances?” His response was: “My child, if you know the song, you can sing it however you want.”