Stylist Kamilla Akhmedova and photographer Kamila Rustambekova explore the uniquely designed doors to the traditional neighbourhoods—mahallas—of their native Tashkent. Marking the borders of local communities, the distinctive style of each door mirrors the characteristic features of these areas.

Sometimes, you might feel like a tourist in your own hometown. You wander around the city and seem to be teleported to another life. For me, it has become a kind of ritual, and now, when I want to recharge my batteries, I always go to the old bazaar or to the mahallas. Especially to the old ones.

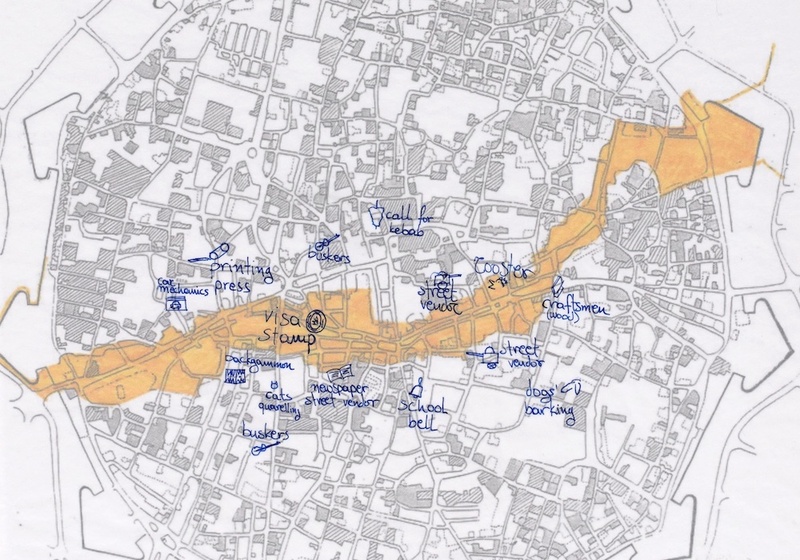

Mahalla is something like a self-governing quarter where all the residents know one another and are very close-knit. Here you can see kids flying kites, elderly men playing backgammon, and covered women watering the ground. Mahalla is a place where you will always be greeted, offered fruits from people’s private gardens, and provided help if needed because both the doors and hearts are always wide open.

I find Soviet doors to be the most beautiful. They are often painted yoghurt-like or bright colors as if to symbolize summer. You cannot confuse them with anything else. Now, such doors are not as numerous as before since construction works are carried out chaotically in Tashkent. The owners of public and private territories favor new residential areas and there is a decreasing number of people who are eager to preserve the old look of the city.

But there are also exceptions. For example, this year the Art and Culture Development Foundation under the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Uzbekistan is taking part in the Venice Biennale of Architecture with a pavilion that has chosen the phenomenon of the mahalla as its subject. So, I thought it was a good reason to make a text about it and invited the photographer Kamila Rustambekova (who completely shares my love of the mahalla) to take pictures of these very Soviet doors.

As it turned out, not so many people know the stories behind mahalla doors, so we have enthusiastically reconstructed them by collecting fragments of information. We started with the artisan stalls near the Chorsu bazaar where craftsmen shared with us the origin of the interesting word “hasham,” translated from Old Uzbek as “aesthetics.” If translated literally, it means the soul and creativity that the “usto” (the master) puts into his creation. The doors also represent the style of a particular artisan.

One could experiment with various notches,

while others come up with something unique

or rethink the round shape, which is commonly known as “kulcha” (after a popular type of flatbread)

Another craftsman, Sirojiddin Rakhmatullaev, told us that one of the patterns was actually inspired by oriental wall paintings.

The painting practice itself is now gone, but its geometric form has remained.

Otabek Karshiev, a collector from Tashkent, suggested that such doors could have been imitating the front doors from the Russian part of the city.

In “Russian” mahallas, such doors mainly belong to the pre-revolutionary period, while in the old part of the city they are sixty to seventy years old.

This style could have been brought here by Tatar masters from Ufa and Kazan.

The upper part, the transom, is not typical for Uzbek doors either,

although it does suit the local climate.

Thanks to transoms, yards are well ventilated, saving mahalla inhabitants from the heat.

As for the colors, they are usually chosen by the craftsman.

Most often, they are of turquoise, sapphire, peach, or milky white colors,

while darker ones, such as brown, are used in neighborhoods with fewer trees.

This is done in order to avoid the necessity of frequently repainting the doors: exposed to the sunlight, they might quickly lose their color.

Each door is like a mirror of its creator.

I am glad that despite the popularity of plastic, you can still come across original mahalla doors. Also, I am happy to encounter doors that were made before the revolution. Let’s hope they will be preserved for a long time.