In 2021, members of FLEE project and Ored Recordings conducted ethnographic recordings and interviews in Ulyap, a village in the North Caucasus where one can find an enormous number of accordion and harmonica players. Ulyap Songs: Beyond Circassian Tradition, released as a book and LP on January 19th, 2024, is the result of their attempt to document the musical history of local bards and to better understand their entanglement with popular rural heritage as well as Soviet culture during modern times. To celebrate this exciting release, EastEast is sharing an essential chapter from the publication by the scholar Lina Tsrimova.

Toward a History of the Adyghe Folklore Studies in the 19th and 20th Centuries

The taste for Caucasian folklore as an exotic Oriental phenomenon was part of the colonization of the Caucasus. Ever since their 19th century conquest, Caucasia has drawn the eyes of Russian colonizers and orientalists, often amazed by its “lack of civilization.” But the first published writings on the Caucasus did not appear until the end of the century, when enthusiasts of the Caucasian exoticism—officers and poets such as Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov—gave place to professional scientists who were advised by the first Russian-educated local intellectuals.

Unlike in the 16th century, when the daughter of a Kabardian ruler could marry the Russian Tsar Ivan the Terrible, in the 19th century, the integration of Muslims into the Russian elites was difficult. This, among other factors, contributed to the fact that integration, education, and, consequently, national and political movements in the North Caucasus and Azerbaijan were weaker than in the Christian areas of the Caucasus (such as Georgia, Armenia, and to a lesser extent Ossetia). Adyghe intellectuals, such as Pago TambievPago TambievPago Tambiev, or, in Adyghe languages, Tambi Pagua, Ismail's son (1873-1928) was an Adyghe educator, intellectual, and collector of folklore., did not believe they had the right to call themselves “intelligentsia.” At the same time, Tambi was interested in modernist projects (both Islamic reformist and socialist) in education and the development of a writing system; his collaboration with the orientalist scholar Lev Lopatinsky and his collecting of Adyghe folklore and its translation into the Russian language can be regarded as a contribution to the establishment of the Adyghe nation and writing system.

After the October Revolution in 1917, the Bolsheviks’ policies concerning non-Russian cultures were contradictory. On the one hand, the Soviet government launched a policy of korenizatsia (lit. “rooting,” meaning indigenization) to create local, non-Russian elites who could govern the Soviet republics. On the other hand, they believed popular cultures to be backward and headed toward oblivion. The folklore policy took a dramatic turn when Joseph Stalin came to power, a figure whom some historians, such as Sheila Fitzpatrick, describe as a neotraditionalist.

Tambi died in 1927, on the threshold of revolutionary changes that brought on enforced collectivization, industrialization, terror, and political repression. The first collection of “Kabardian folklore”“Kabardian folklore”Broydo G.I., M.E. Talp, Sokolov Yu.M. Kabardian Folklore. Moscow, Leningrad: Academia, 1936. The list of authors alone shows that the role of the actual Adyghe intellectuals was minimized, obliterated. published since the October Revolution (in 1936), accused Tambi of “trying to save aristocratic folklore from extinction and at times descending to the falsification of documents.” Some of the most popular songs of the so-called “aristocratic folklore” were banned, as were the writings of Tambi. The 1936 collection did not feature a single original text, as it was written in the “language of progress,” i.e. the Russian language. It had, however, many orientalist, pseudo-Adyghe terms on its pages, such as sakli (the Russian name for the huts of Caucasian highlanders) and sharovary (men’s pants worn by Cossacks), terms that had entered the Russian language when the literary Caucasus was invented by Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov, among others, in the literary lab of Russian colonialism. The text also contained some words of Circassian origin, such as tkha (god), uork (a nobleman) and unautka (domestic servant). All of these words were listed as “archaic” in a separate dictionary at the end of the book.

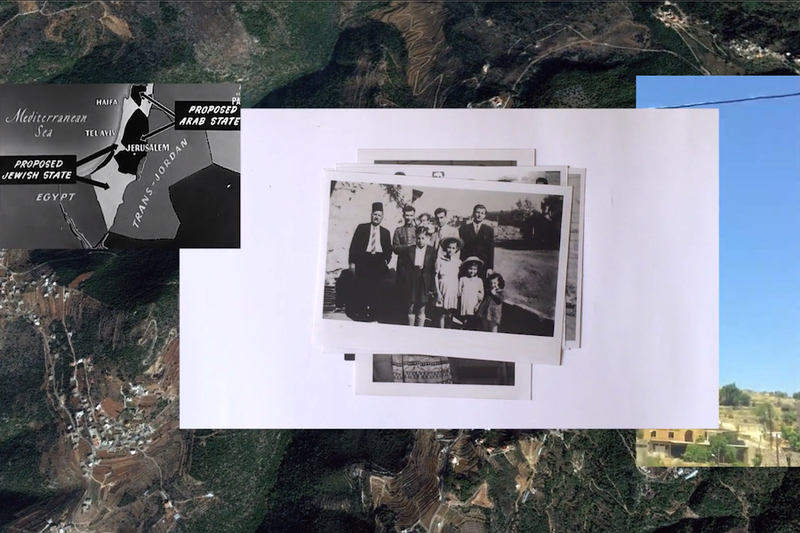

Circassian musicians. Adygea, 1920s

Private Archive

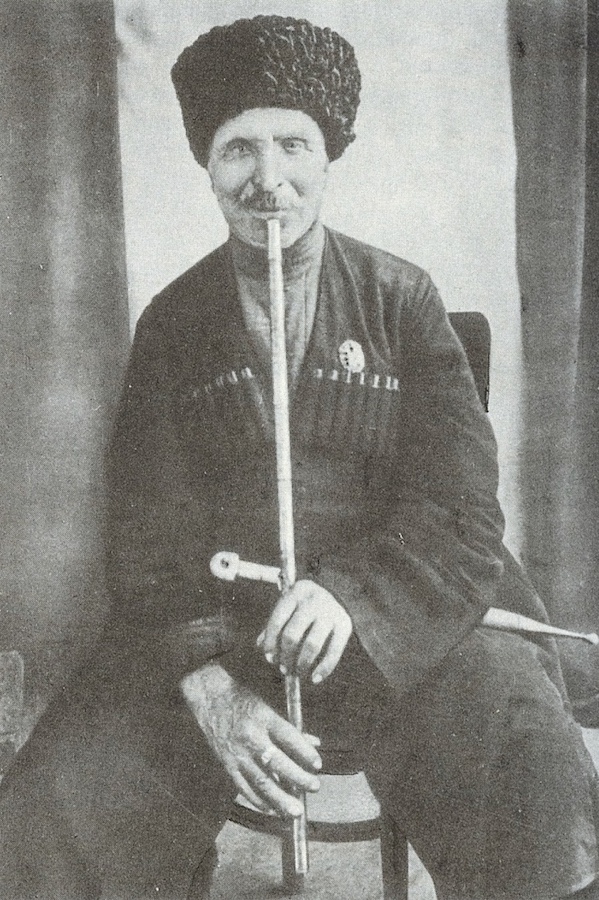

Kilchuko Sizhazhe. Zayuko village, Kabardino-Balkaria, 1930s

Private Archive

Circassian musicians during a celebration. Adygea, 1930s

Private Archive

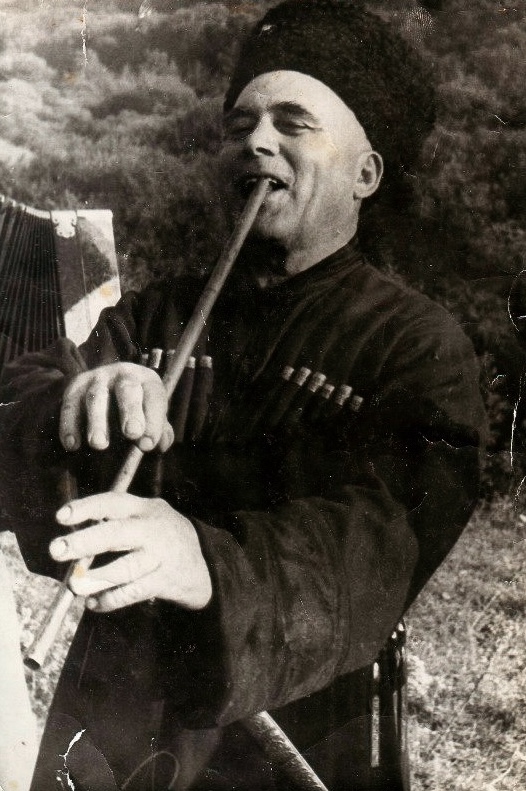

Alaudin Leinshe, kamyl player and musician. Karachay-Cherkessia, 1960s

Private Archive

The impossibility of translating these religious or class-related terms into the Russian language suggested to the reader that those elements of the Kabardian culture were unintelligible to the contemporary Soviet reader. On paper, it was a study of an ethnic culture, but in fact the book presented a Soviet interpretation that had no space for the polyphony of Adyghe voices.

Also in 1936, Kabardian became one of the first languages that transitioned from the Latin to the Cyrillic alphabet, soon followed by the Adyghe language (Western dialects of the Adyghe languages), and the Soviet Adyghe people were further separated from the diaspora in Turkey and the Middle East. The development of writing and the recording of folklore in the Cyrillic alphabet picked up after the Second World War. In the 1950s, numerous expeditions came to collect and record Adyghe folklore, and in particular, its most important cycle, the Nart sagas.

Soviet ethnographers themselves observed that the oral culture was being replaced by a written one

Due to the work of Asker Gadagatl, several collections of epic poetry were published in those years. Recordings of the bearers of the oral tradition were gathered for archives in Adygea and Kabardino-Balkaria. At the same time, the postwar years dramatically changed the cultural and linguistic situation in the region: Soviet ethnographers themselves observed that the oral culture was being replaced by a written one. In the 1960s and 70s, new generations of the Adyghe who now studied in schools for long periods of time, had better access to the writings of Soviet ethnographers than to the oral epic tradition.

The spread of folklore radio recordings by performers such as Zyramuk KardangushevZyramuk KardangushevZyramuk Kardangushev, or, in Adyghe languages, Zyramuk Kardangush, Patura’s son (1918-2008) was a Soviet Kabardian writer, poet, folklorist and singer. He took part in ethnographic expeditions to collect the Nart epic and initiated the publication of the two-volume collection "Adyghe Folklore" in the Kabardian language. had a significant effect. His rendition of Adyghe songs became “classical.” In general, the postwar years were the time of rupture for the oral epic tradition such as it had existed for centuries, as well as a period of patrimonialization. The aesthetic forms that Soviet ethnographers presented as traditional—both in music and poetry—became “authentic” and “the canon” for many Adyghe people.

After the death of Stalin, the ideological pressure in folklore studies relaxed. Along with the publication of previously unpublished texts, different interpretations of folklore in the context of Adyghe history emerged. The key figure in this movement was Zaur Naloyev. Drawing on Mikhail Bakhtin, Naloyev proposed his own interpretation of the development of the Adyghe culture from antiquity to the modern age. He argued, in particular, that peoples that developed their writing systems recently, passed three stages of cultural development: folklore (the oral tradition of working people), pre-literary forms associated with the emergence of bards or dzheguako, and finally, modern literature. Naloyev saw the dzheguako as a figure of particular importance and a figure of progress in the period from the 15th-16th century to the conquest of the Caucasus by the Russian Empire (and the arrival of Western modernity with it). Thus, folklore, according to his theory, was not a homogenous phenomenon, but developed with time until it reached Soviet modernity.

Right: Private collection at a villager’s house. Ulyap, Adygea

Below: Mountains in the region of Verkhnyaya Balkariya, Kabardino-Balkarian Republic

Photos by Olivier Duport, 2021

One of the important effects of this modernity was the creation of three Soviet national identities in the place of the unified Adyghe identity, based on the Soviet administrative organization: the Kabardians, the Circassians, and the Adyghe. One of the main performers of Adyghe epic songs, Zamudin Guchev who born in Kabardino-Balkaria, recalls that in Adygea he discovered the essential elements of his culture that had been “eradicated as part of the cultural revolution”: the guest house (khyeshch’eshch) and the traditional fiddles (shychepshyn). Unlike the previous generations of ethnographers and performers such as Kardangushev, Guchev paid great attention to the performative aspect of his singing: he used ancient instruments and performed in spaces that imitated the atmosphere of traditional guesthouses where epic songs were performed.

The aesthetic forms that Soviet ethnographers presented as traditional—both in music and poetry—became “authentic” and “the canon” for many Adyghe people

At the same time, Adyghe ethnographers ignored their contemporary popular culture: for example, the archives of the time have no recordings of songs from Ulyap. Guchev believes that these songs, just like the accordion that accompanies them,

“have come from Russian culture, together with vodka. In the ancient love songs, people did not speak about their feelings . . . the relationship between the man and the woman was not discussed. There was chivalry, and there was no sentimentality—it would belittle a man. But today, we are hardly Adyghe. We are now trying to show that we once had something, but very little of it remains today. A lot has come from other people, from alcohol . . . all these Yura-Shmura and the new masterpieces.”the new masterpieces.”From a 2022 interview with Lina Tsrimova

The fall of the Soviet Union was closely connected to the national question and the national movements that gathered momentum in the end of the 1980s. Moscow was increasingly unable to solve local conflicts and persecute the unwelcome activists. Calls to exercise the peoples’ right to self-determination proclaimed by the Soviet constitution multiplied. In most republics, the national movements were headed by local ethnographers, historians, and archeologists, who were held in higher moral esteem than the Soviet establishment.

The Adyghe republics were no exception: the head of the national movement Adyghe Hase was the abovementioned ethnographer and historian of culture Zaur Naloyev. This was a brief but exciting period in the history of the Adyghe intelligentsia, which did not succeed in separating from Russia, but succeeded in creating the Republic of Adygea within the Krasnodar Krai, and in popularizing the Adyghe culture and the Circassian language.

Photo by Olivier Duport

The Adyghe epic songs became an indispensable part of various memorial practices, including those commemorating the victims of the 19th century colonial wars and the exodus of the Adyghe people, which is one of the key narratives for the contemporary Adyghe identity.

However, the heyday of the national movement was short and took place against the backdrop of many local conflicts and the wars in Chechnya (1994-96) and Abkhazia (1992-94). Economic and industrial decline resulted in mass migration within the region from non-Russian villages to previously Russian cities—as well as a mass exodus of ethnic Russians. The previously marginal criminal chanson culture became truly ubiquitous, and the first commercial chanson projects emerged in a liberalized and commercialized economy. But, when Vladimir Putin came to power in Moscow, the Russian government started building what they called “the vertical of power,” crushing local sovereignty and independent political life in the non-ethnically-Russian republics, and in particular in the North Caucasus.

Many young and educated people who will shape the future of ethnic cultures have left the North Caucasus

Popular elections of the republics’ presidents were abolished—in fact, the very title “president” was replaced by “governor” upon suggestion from the pro-Putin head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov. Compulsory teaching of the national languages in schools stopped and the local universities that educated teachers of these languages fell into decline. Despite their different approaches to the Adyghe song culture, Zamudin Guchev and Yura Nagoyev agree about the general sense of a deep cultural crisis.

Today, like many cultures of non-Russian peoples within Russia, the Adyghe culture is in a deep crisis and under the pressure of intensifying censorship. After the start of the war in Ukraine, the local authorities have launched several persecution campaigns against intellectuals and activists. Many of them had to leave the region. Along with them, many young and educated people who will shape the future of ethnic cultures have left the North Caucasus. The war in Ukraine has put into question the existence of Ukraine, but also of Russia as an Empire (which it has essentially been over the past few centuries), and consequently, the future of non-Russian ethnic groups within Russia. The life and development of these groups and their cultures will depend on the outcomes of this war.

For more information about Ulyap Songs: Beyond Circassian Tradition, visit the FLEE Project website.

All the images provided by the authors.