Photo by Salma Sherif

The music of Aly Eissa is a unique sonic force, projecting outward from all sides of Cairo's contemporary music scene. His long list of mentors from the more traditional fields of classical composition and performance, coupled with his eclectic taste and personality, result in a musical output that resists categorization. Musicologist Tucker M. Wiedenkeller reflects on his many conversations and engagements with Aly Eissa, unraveling his musical history and chronicling his "constant desire for progression."

Drifting through the ether on a boat of nacreous composition, weathering electrical storms and crystalline rain. The ship lands, you’re somnambulating through a dusky cabaret from a fictitious future. Emotions and nostalgia from a parallel dimension greet you like faceless old friends. Where you are is out of time. You settle into a chair in this atemporal carnival and embrace the suspense of reality, riveted by the unusual experience that is the music of Aly Eissa.

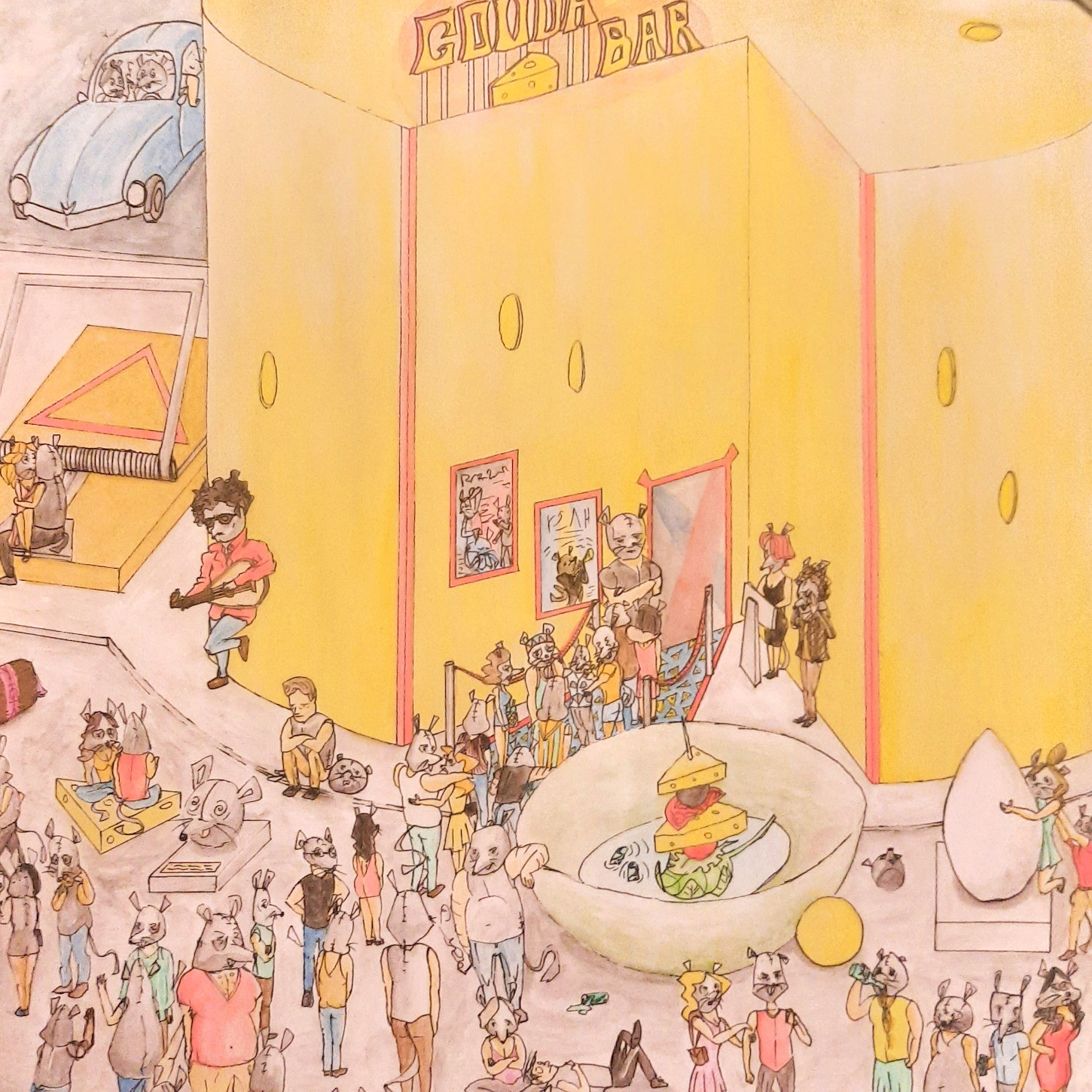

Each Aly Eissa song is an epic, voyaging through myriad emotions, evoking distinct chapters and plot twists, calling forth whimsical imagery. Emotive but not melodramatic, his music can pivot from kaleidoscopic ambiance to vehement tremor. Seeing him perform his album Gouda Bar (2023) at Cairo Jazz Club last year, the energy in the room was euphoric, the audience enraptured by the atmospheric dialog between synth and oud, breaking into full-blown, all-members-on-deck cacophony.

One of the first times I hung out with Aly Eissa, he picked me up outside the metro in his old maroon Mercedes, wearing a turtleneck and classic Ray Bans. Walking around the verdant Cairo neighborhood of Maadi where he was born and raised, we talked about Egyptian folk and popular music, of which his favorite era is the ‘30s–‘70s (for all music), and his love of old synths and organs. Though I didn’t know it at the time, I had seen Aly play in 2017 with revered violinist and composer, Abdo Dagher.

Aly Eissa (b. 1993), when not working as a dentist, is one of Cairo’s most compelling contemporary composers. Long and roaming, his subtle compositions draw from traditional Arabic music before wandering to liminal, unheard-of places. His penchant for older music and synths casts a retro hue over Aly’s music, though he gracefully dodges cliché. Primarily an oud player, Aly is largely self-taught. That said, his mentors have included Abdo Dagher, Hazem Shaheen, and Mohamed Antar—a few of the most treasured names in contemporary Egyptian music.

Where you are is out of time. You settle into a chair in this atemporal carnival and embrace the suspense of reality, riveted by the unusual experience that is the music of Aly Eissa.

Aly’s universe is as complex and full of surprises as his compositions, and his abounding quirks are made known at his leisure and discretion. Viewing Cairo through his eyes means becoming privy to little-known corners, such as weirdly located foul foul A breakfast dish, originating in Egypt, traditionally made by mashing fava beans cooked with cumin and then serving with olive oil, garlic, lemon juice and chopped fresh parsley.carts (think the corner of an empty dirt lot across from a military hospital). His most recent obsession is having bespoke pants made, regularly visiting his beloved downtown tailor ‘Am Adel to scrutinize designs.

Hailing from a family of music lovers, Aly was exposed to diverse styles in his childhood: “Music was there romantically . . . in the air of the cars and the home and everything.” While his father is passionate about the Golden Era Egyptian music of the ‘50s and ‘60s, such as Umm Kulthum, his mother is more versatile, listening to Egyptian pop from the ‘70s, Western pop, and classical. “My mother can listen to a special song and she cries.” Finally, sharing a room with his brother, Aly absorbed everything from techno, to rap, Limp Bizkit, blues, and jazz.

From the age of three, Aly was singing in Arabic. “Everyone thought I was going to be a singer, but this never happened.” At 13, his brother took him to buy his first instrument—a guitar. He attacked it with vigor. Teaching himself by ear (a theme that will persist throughout Aly’s career), he was soon playing Nirvana, Metallica, and even some jazz standards. “That was my toy in the house, my video game.” He received his first lesson from a peer in his Aikido class, a metalhead who taught him chromatic exercises. At this young age, Aly even began to compose.

Eventually, he began to play some Arabic music but was challenged to recreate the quartertones found in Arabic maqam. The first song he attempted was “El Nahr El Khaled” by Mohamed Abdel Wahab. “The third verse has an oud solo in the beginning. It is rast (a common maqam) and I couldn't play it. I played it in major (the closest Western scale). I played for my brother and my father, and they didn’t like it.” This marked the beginning of his transition to oud, at least mentally: “Instead of playing air guitar while making breakfast, I was playing air oud now.”

The conversion to oud was complete after his parents took him to see Naseer Shamma at the Cairo Opera House, a tribute event for a famous journalist. “My father was in the leftist communities.” Despite Aly having broken his eyeglasses that day playing volleyball, he was spellbound. “I'm blind—I'm legally blind. I couldn’t see Naseer Shamma but I remember everything . . . my hands were red from clapping.” His mother took him to take a photo with Shamma in the lobby, and sight-challenged Aly approached the man with the oud; it was not Shamma, but rather his assistant. “I shook hands with that guy . . . I told him, ‘I love you!’” Aly remembers, bursting into laughter.

His mind was made up. Aly hounded his parents for an oud, and after acquiring one from the famed Mohammed Aly Street, he immediately tuned it like a guitar. He played like that, teaching himself, for 7 more years. “I even did 40% of my compositions with this tuning.” Once he finally moved to the standard Arabic oud tuning, he was enchanted by the new resonance and overtones. Less enchanting was the three months it took him to relearn his own pieces.

By this time, the 20-year-old Aly would make a formative discovery—the music of Abdo Dagher: “2013 was the year of Abdo Dagher. I used to listen to him every day on loop. I've never been crazy about anything like that in my life.” In true Aly fashion, he learned all of Dagher’s material, and despite feeling very confident with his playing, decided to study with Dagher’s oudist. “At this time, I had this false pride . . . I was full of myself. Why would I meet Hazem Shaheen?” His delusions of grandeur were quickly shattered: “From the first lesson, I discovered that I didn't know anything.”

Reducing Hazem Shaheen to Abdo Dagher’s oud player is unjust. Shaheen, from Alexandria, is one of the world’s most formidable oud players, and in 2002, was deemed "The Best Oud Player in the Arab World" in the International Oud Competition in Beirut. Like many younger players in Egypt, he studied with Naseer Shamma. Though Shamma himself is Iraqi, in 1999 he set up a school in Cairo, the Arabic Oud House, disseminating his style of oud playing largely based on the floating-bridge oud. However, Hazem is not necessarily a poster child for this school of oud playing; his style digs deep into the Egyptian popular heritage of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, filtered through his own supernatural virtuosity. To many, he remains famous for his revolution-era band Eskenderella, which gained notoriety playing in 2011 Tahrir Square during sit-ins, covering the songs of turn-of-the-century revolutionary musicians Sheikh Imam and Sayed Darwish.

Aly requested that Hazem teach him Abdo Dagher’s music. “I already knew it but without good style. He’s a good keeper of Dagher’s heritage . . . he loves him so much. ” And so Hazem taught Aly with modesty and generosity, imparting his personal style and technique. The mentor’s meditative approach stuck: “He says that a single note is enough. You can get high on a single note.” Despite Aly’s initial dismissiveness, he now credits everything good in his playing to Hazem. “I even play my music better after seeing Hazem.”

“He says that a single note is enough. You can get high on a single note.”

Before he met Hazem Shaheen, Aly attended an Abdo Dagher concert at the Cairo Opera House, a sold-out double bill with pop mega-star Angham. While waiting in line, he fortuitously met another man who was also there for Dagher, a forty-something engineer and amateur singer. Impressed by Aly’s youth and musical preferences, he boasted of knowing Dagher personally.

Aware that Dagher’s home was often full of musicians, Aly began to cling to the man from the ticket cue, hoping it would lead him there. After a five-month period, “he took me there and mentioned to Dagher ‘Listen, this young guy is crazy about you.’” Finally granted an audience with his hero, Aly played Dagher’s own compositions for him.

Aly began going to his house every other week, though at that time Dagher wasn’t playing as much, hindered by the death of his wife, a new marriage, and health issues. “In the past, during the 1990s or early 2000s, he used to play daily”. Though unsure if Dagher was entertained by their meetings, Aly persisted.

By now, Aly had begun to study dentistry, the family vocation. “I remember on a Monday my phone kept ringing. I was there in my father's clinic and my brother came and told me, ‘Okay, leave what you're doing, I'm gonna replace you now because ‘Am Abdo is calling you’. I thought it was ‘Am AbdoAm AbdoReferring to Abdo Dagher, “‘Am” translating as “Uncle.” the mechanic downstairs and someone hit my car.” Dagher was calling Aly to come rehearse for a performance. Aly was surprised—“Before this. I thought he didn’t like me.”

Aly had been called to fill in for Hazem Shaheen. However, an hour after he arrived, Hazem walked in due to a mix-up. “I asked Hazem, ‘Do you want me to go on stage or not? I feel it's inappropriate, you're my mentor’.” Despite it being uncommon practice for an orchestra to have two oud players, they both performed. Aly was touched by Hazem’s graciousness and guidance, playing at low volume out of respect.

In 2016, the Arabic Music Institute in Cairo offered Dagher a position teaching a violin course, and he brought Aly on as his assistant. They would meet twice a week in that period, once to teach, and once to play at Dagher’s home. “On Tuesdays, the vibe of Abdo Dagher’s place was back again.” During that time, a shift happened in their relationship, becoming “like grandfather [and] grandchild. People would call me to reach Abdo Dagher. He would call me just to share a story about something he watched on TV.” Dagher’s death in 2020 represented a huge loss for Aly. “I was there until the day he passed away . . . in his daily life with his family, out of love.”

When I ask Aly if he ever played his compositions for Dagher, he gets bashful. Fascinated by Aly’s music, Dagher urged him to give up dentistry and pursue music full time. “He even attended my first performance at the small hall of the Cairo Opera House in 2018. He arrived 30 minutes late and we didn't start until he came.” Though his double life as a dentist continues, Dagher’s encouragement pushed Aly deeper into what is already second nature: composing.

When Aly began to play music, he would compartmentalize his time. Some sessions he designated for covering songs, whereas others were devoted to composing. “I [would] just start to improvise until I reached a good sequence or idea, but this time was dedicated to composition . . . [to] find a language of mine.”

Reflecting, Aly realizes he preferred this free, innocent period of creativity, unhindered by musical knowledge or expectations. Now, it takes him “a much longer time to reach an idea, because I have a richer background compared to what I had in 2013 . . . I hate it now, before it was so fresh and childish and everything worked.” Because Aly never had a traditional education, he composed freely in lieu of using classical song forms such as sama’i or peşrev. He doesn’t feel that Arabic classical music need be “the exclusive path or route an Arabic musician would take.” At one point, he also realized that he need not emulate the compositions of his mentors; one’s creative output “has to do with socioeconomics . . . with [your] childhood and the movies you’ve watched, the books you’ve read . . . It’s more holistic . . . it feels better not to be blindfolded into learning.”

Now, it takes him “a much longer time to reach an idea, because I have a richer background compared to what I had in 2013 . . . I hate it now, before it was so fresh and childish and everything worked.”

When he is emotionally stimulated, Aly runs to his oud. Sometimes ideas come to him while walking or showering, humming improvisations that he later translates to strings. On occasion, it’s good technique that begets a nice sequence: “Sometimes the thought comes before the technique and sometimes the technique is just to fulfill the thought.” Aly’s compositions reflect a comprehensive aesthetic world in his head that blooms out into his material reality. “Every name of a piece I have is linked to some fantasy or some trip I had in my head. I'm so loyal to these images. Sometimes it’s just geometrical patterns, colors, a chair, people or faces, or just an emotion. It’s nice to link an emotion with a musical line with a geometrical pattern. It feels like a good union.”

Listening to Gouda Bar, the oud is suspiciously absent from the forefront; that’s because Aly wrote it for his other love, synthesizer. He was first exposed to synth through Daft Punk, and felt he wanted to be “up to date with these sounds,” ironic considering the age of Daft Punk’s music at the time. “I have to be down to date,” he corrects himself with a laugh. A careful listener, Aly concluded that in most electronic music, the melodies were not complex.

Later, he would meet Jonas Cambien, a Belgian synth and piano player based in Oslo with a jazz, classical, and free improv background. This auspicious meeting would alter the sound of Aly’s music. Inspired by Jonas, he began to compose melodies that would normally be played by oud or violin, for example, and send them to Jonas to materialize on synth. He thought, “Let’s get this sexy patch of sound and play some complex structures,” something he says would never have happened without Jonas. What came out of this collaboration was the music for Gouda Bar. “He liked the idea, I liked the idea, it went there, and it was nice.”

Aly claims he named the album Gouda Bar because he considers the music somewhat cheesy. Last year, having breakfast with Aly and Jonas at Aly’s grandmother’s apartment in Maadi, I was given a different explanation. As we sat on the balcony eating Aly’s signature eggs, I asked him about the title.

He responded with a question of his own: if I had ever watched Tom and Jerry. A huge fan himself, Aly insists we watch the “Rock n’ Rodent” episode. Suddenly, the album artwork, by Aly Gaafar, made more sense. It pictures a crowd of mice mingling outside of the “Gouda Bar”. A mouse that looks suspiciously like Aly, down to red jacket and Ray Bans, leans on the wall outside with an oud.

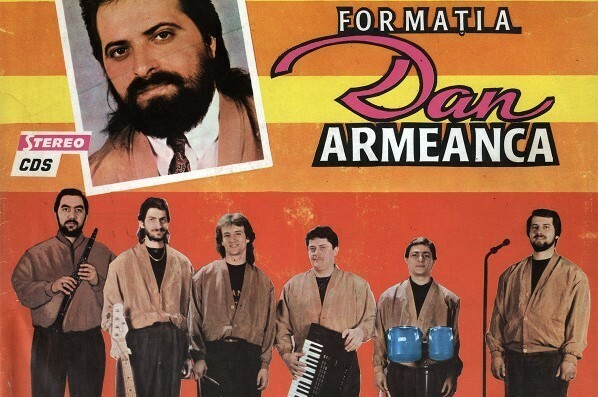

Right: The Handover: Jonas Cambien, Aly Eissa, and Ayman Asfour

Photo by Omar El Kafrawy

Cambien would join Aly on stage at the Cairo Jazz Club for the first Gouda Bar gig in 2018, years before the album was released. The ensemble started as a quartet; in addition to Aly and Jonas, percussionist Ayman Mabrouk and violinist Ayman Asfour were critical members. Over the years, the sound developed and Aly bolstered the lineup. Violinist Andrew Nasser, keyboardist Sohieb Elnaggar, and trumpeter Mohamed Sawwah would join, as well as sagat sagat small metallic cymbals used in belly dancing and similar performances.player Aref Elhalwani.

The Farfisa Farfisa An Italian electric organ popular in the 1960swould become an implemental component of the Gouda Bar sound, imbuing it with the nostalgic cabaret pop of the Egyptian past. “I had an image of the soundscape. I needed the synthesizer [to be played] by Jonas . . . but I also wanted Soheib Elnaggar to play the Farfisa like Magdy El Husseiny and Hany Mehanna from the ‘60s and ‘70s, in a heavy percussive way.” He brought in the violin and trumpet to further mimic the takht, or Arabic backing band. The trumpet especially drives home the old-school chaabi sound, reminiscent of Ahmed Adaweya’s work with trumpeter Sami El Bably.

Gouda Bar is a sort of cosmic space chaabi, evoking the sound of a retrofuturist Egyptian cabaret. It calls forth images of "ayam zamanayam zamanArabic phrase meaning “the good old days”" with a sci-fi twist. It nimbly migrates from exuberant, soaring dance music with twinges of big band jazz (“Barrel’s Dance”), to seraphic, tender nap-in-the-late-afternoon-sun ambiance (“Virgin”), a loping cadence through atmospheric emptiness into exultant carnivalesque whimsy (“Camel”), and unhurried çiftetelli taksim overcome by bouncy unified pizzicato and Arabesque violin (“Gouda Bar”). The title track is an ideal belly-dance number, capable of all the intensity, ardor, and melancholy of Arabic tarabtarabRefers to traditional forms of Arabic music which are capable of inducing a specific emotional effect.

without crossing into melodrama or schmaltz. The album was recorded almost entirely live in the studio. “I wish I could have recorded it like in the ‘60s, all in one big room with proper micing, but I met so much resistance,” he reflects.

This “resistance” that Aly mentions is part of a larger disconnect he feels with the Cairo music scene. Though he recognizes his relationships with musicians, “I don’t think I’m part of the scene, if there’s something called that. I’m doing my thing,” adding that stylistically, he’s a bit of an outlier.

That’s not to say that no one from Cairo inspires him. He mentions Maurice Louca, whom he has played with in the past, and Adham Zidan’s project, Baskot Lel Baltageyya (“cookies for thugs”). “I have no memory of a better live performance in years,” he says of a show we both saw last year preceding Baskot’s debut album, released alongside Gouda Bar on Akuphone. However, both Louca and Zidan are residing in Europe with occasional stretches spent back in Egypt. The lack of venues in Egypt—one of Aly’s main gripes—has driven many artists to seek success abroad.

Adham Zidan, a key figure in Cairo both as musician and studio engineer, helped master Gouda Bar. Zidan has lent his touch to countless Egyptian projects, particularly those on the avant-garde side like Maurice Louca, Nadah El Shazly, Nancy Mounir, Tamer Abu Ghazaleh, Youssra El Hawary, and Dwarfs of East Agouza. He is also a member of The Invisible Hands with Alan Bishop, the Lebanese-American behind The Sun City Girls and seminal record label Sublime Frequencies.

“I don’t think I’m part of the scene, if there’s something called that. I’m doing my thing,”

The musicians that inspire Aly most, his “musical soulmates,” are Jonas Cambien and Ayman Asfour, who he says share “similar fantasies” as himself. They have now moved hand in hand with Aly to his current project. At 50 minutes, The Handover explores “the common and uncommon senses of Egyptian countryside music,” vacillating between dashes of profound tarab, roguish improvisations, and Egyptian street wedding keyboard. “It is spacious and abundant and it accepts,” Aly says. Released on Sublime Frequencies in April, The Handover is Aly’s favorite project yet. Cambien says it is blessed with an “almost telepathic communication between the three musicians.”

Regardless of whether Aly considers himself part of a musical scene, he is inevitably part of a community, weaving unconventional threads into the sonic tapestry of Cairo. His music dances delightfully on the knife edge between new and old, familiar and unfamiliar. It feels like a cathartic release of something seductive brimming around us, as if Aly has tapped into a neglected vein of the Egyptian musical ethos and channeled it through his colorful inner realm. An enchantment of Aly’s music is that the line between composition and improvisation is often blurred—I am often mystified as to how the musicians around him memorize such slippery, elusive music. His theory of the “common and uncommon” accurately sums up Aly’s overarching musical sensibility: he is steeped in the music he loves, but draws from this reservoir to reach into realms unknown. While the common sense fortifies him, it is the hunt for the uncommon that drives him, the constant desire for progression.