The heritage of Muslim cameleers in Australia is one of the lesser-known chapters of colonial history. Brought by the British, they worked hard to establish a network of tracks, telegraph lines, and railroad connections across the continent. Artist Elyas Alavi shares the beautiful discoveries he made during his research for a commission at the Biennale of Sydney.

Poetic Beginnings

I was born in a small village in the central part of Afghanistan, in the Daikundi province. It's beyond Bamiyan, which is known for the big Buddhas that were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The central part of Afghanistan also known as “Hazarajat,” which means the land of Hazaras. I am myself of Hazara background, and throughout history, there has been a lot of discrimination against our people, including genocide.

Many of our people had to leave the country, mostly going to neighboring countries of Iran and Pakistan. We left in 1989 due to the civil war caused by the Soviet Union invasion. We went to Iran, where I lived with most of my family for a long time. Then I moved to Australia in late 2007.

I always wanted to do art, but for me, it started with poetry. Poetry was the most accessible way to express myself. I published my first book in Iran in 2007, then a few years later I published a book in Afghanistan, and a third one was published again in Iran around 2015. My books are now banned in Iran.

I work in different mediums, mainly painting and installation, as well as performance featuring my poetry, often in collaboration with experimental musicians. I also do a bit of video, but it really depends on the project and what medium fits best.

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Photo: Andrew Curtis

Photo: Cassandra Hannagan

Photo: Cassandra Hannagan

Photo: Jacquie Manning

Photo: Cassandra Hannagan

Cameleers

The work I showed at the Sydney Biennale was made specifically for the project, but I had been researching the topic since about 2021 when I started studying the history of cameleers in Australia, known as Afghan Cameleers. These cameleers were brought to Australia as cheap labor through the inter-colonial networks of British India between 1860-1920. The origins of the majority of these Cameleers include communities from contemporary Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and K,ashmir.

I traveled to outback towns including Port Augusta, Oodnadatta, Coober Pedy, and Marree in South Australia and Broken Hill in New South Wales state. In Marree, there's the biggest cemetery of cameleers, and there’s still a big group of their descendants living there.

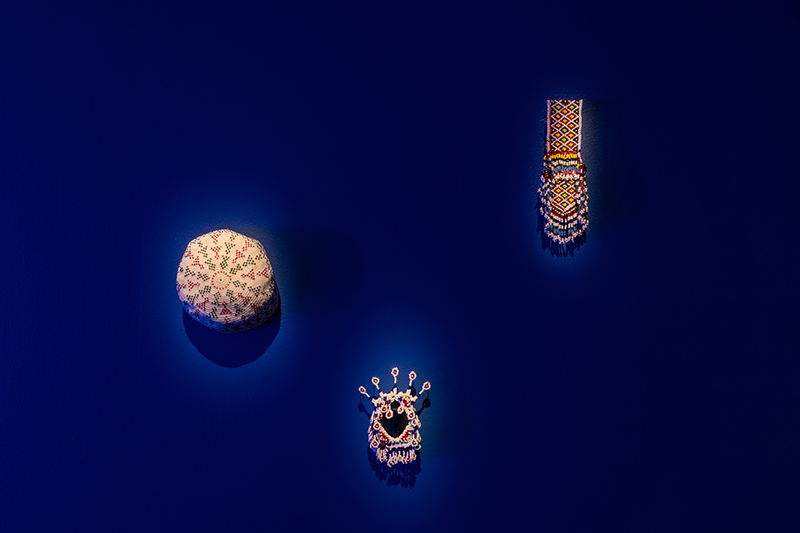

In the Broken Hill mosque, I came across a musical instrument. This mosque was built by the cameleers in 1887, in the far regional west. One of the descendants kept some artifacts, books, and materials from his father and asked other descendants to provide the items they had. He turned half of the mosque into a small museum, very simple and humble. I feel it's like the treasure of this history because there you see the books they were reading, the notebooks they were writing, their shoes, hats, clothes, beads, camel saddles, and other equipment.

Among these items, I saw a musical instrument called the rubab. It was mistakenly labeled as a santoor. Seeing that rubab, almost totally broken but still recognizable in shape, was a beautiful discovery. It made me think there were also musicians who had come from the areas of today’s Afghanistan or Pakistan.

Right: Image of the Rubab instrument on display at Broken Hill mosque

Photos by Elyas Alavi

Music

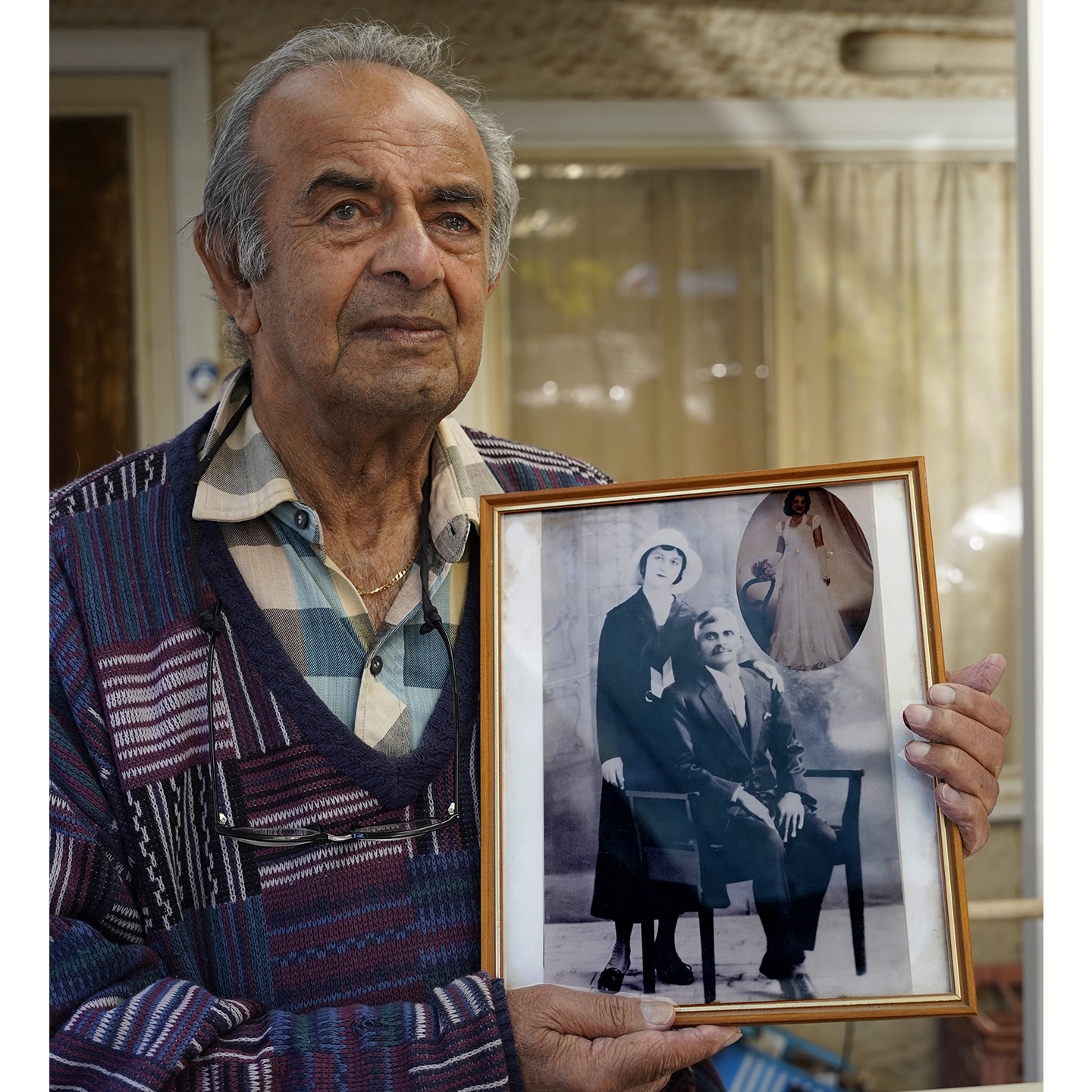

Thus, the music element was my starting point for the Sydney Biennale. I researched and looked around, and luckily, I found a person who had donated the rubab. It was given by the son of a man called Kie Shirdell. I was able to meet his son, John Shirdel, who is 85 years old now. He only has vague memories of his father, as he was only nine years old when his father died, but he remembers his father having this musical instrument and playing it.

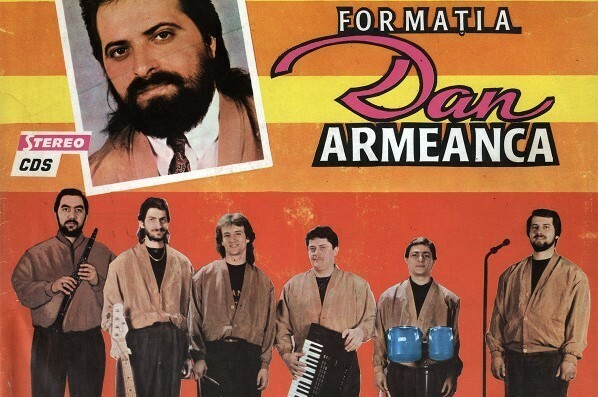

I searched other archives and found another image where cameleers were more likely in an end-of-Ramadan celebration. This picture was taken by a journalist from Western Australia. In it, we see two musical instruments: one is a drum that we call dhol, and another one resembles a harmonium. The photograph is very old and small, without much detail, but the hand gesture of the man may suggest there might be a ney, which is the simplest instrument, close to a flute but with a much simpler form.

I didn’t find much evidence, but I did find one other photo showing a descendant holding another traditional musical instrument which we call the ghaychak. The ghaychak is a double-chambered bowl lute with four or more metal strings and a short fretless neck. It’s mostly played amongst the Balochi people living in contemporary Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Tajikistan.

Neon on Rubabs

The rubab I found was the perfect witness to the history of cameleers.

Through my research, I met a man in Melbourne who had migrated from Herat, Afghanistan thirty years ago and who was a rubab player and maker. We had lots of conversations, and I asked him to fabricate four rubabs for me, which he did.

I made a series of neon inscriptions, trying to find ways to use them on these rubabs. I wanted each rubab to be in a different stage of production. One is in a very raw stage, just the wood itself coming out of the Australian trees, unpainted, no strings attached to it. The next one is more detailed. The third one has strings. The fourth one is complete. I wanted to show the beauty of different sizes and conditions of this instrument.

I wanted to have the sounds of the rubab as well, so in the video we can hear the instrument being played by Nasim Khoshnavaz, a well-known rubab player. He is coming from a family of musicians over generations and his father Rahim Khoshnaz, possibly the best-known living rubab player until he passed away a decade ago. There's also a female singer, Naira Noor, singing to the music.

Memories

For me, this project was about exploring what happens when you migrate or become a refugee. You leave behind many things and loved ones; all that stays are memories and songs. You don’t even use your language much, as you quickly need to learn a new one.

These cameleers came to Australia as cheap labor. They were needed to take camels into the Australian Outback to transport resources, including gold and cotton that was sent farther on to London. They helped build the railway from South Australia to North Australia, now known as the Ghan, a reference to “Afghan.” They also contributed to the telegraph line, delivering water and equipment for at least 60 years, connecting towns that grew bigger because of them—while they themselves stayed disconnected from their own families.

It was hard for them to travel back with temporary visas. They couldn’t bring their wives or daughters, they were only sometimes allowed to bring their strong sons. In most cases they weren't allowed to marry legally, with some exceptions. Many married First Nations women, but these marriages were often weren’t recognized by the government. The government said, “You're Asiatic, and this person is First Nation indigenous. Your children simply won’t be as white.” This was part of the White Australia Policy from the early 1900s, which made life very difficult for them.

From the 1920s and 1930s, after railways were built, the government said, “We don’t need you anymore, you should go back to your country,” and ordered them to kill their camels and leave. But many of them had lived here for 40 years, they wouldn’t be able to go back to Afghanistan or Pakistan because they didn’t know it anymore. The order was to put down their camels but they didn't—they let their camels go into the outback, which is why to this day there is a large population of feral camels in Australia.

I wanted to show how the discrimination they faced mirrors the current situation. These people worked hard for little money to survive, and now, people from the same region, including Middle-Eastern and South Asian communities, face similar prejudices. With Afghanistan's collapse and Australia’s involvement in its politics, we are geographically far but also very close.

Encounters

I also wanted to celebrate the joy and legacy the cameleers had left behind and the proud descendants of cameleers and First Nations. This history connects our communities with the First Nations people who have more than 65,000 years of history.

In my previous work, I focused on the friendship and knowledge shared between cameleers and the First Nations people, imagining their first encounters around a water spring. For that work, I made a circle with book holders, with a word in neon on top of each. Together, the neon words make a full line of a poem by Rumi, which says:

“جان من از جان تو چیزی شنود

چون دلم از چشمه تو آب خورد

My soul heard something from yours

Since my heart drank from your spring

There are beautiful stories about this love, some individual stories which, luckily, I was able to hear from the grandchildren of the cameleers

This work connects to early childhood memories from my village. I come from a mountainous area and visiting small desert towns now, I see a connection in the simplicity and honesty in the eyes of villagers everywhere. There’s a magical welcoming in their eyes, which I gain a lot from mentally and spiritually.

I found friends who invited me to their homes and private gatherings of cameleer descendants in Marree, which has the largest cameleer cemetery. They remember their ancestors by cooking together, playing music, and sitting around a big fire. This simplicity draws me in, and I feel fortunate to have found these connections.

Each connection led to the next. Sadly, some have passed away, taking their stories with them. I wrote poems inspired by stories told by the descendants. For example I met a descendant ,Frank, whose grandparents, a First Nation woman and a cameleer, had to escape from the government to marry. They faced a seven-year long court case and were exiled to a small town. This man was still healthy when I met him, but he had a heart attack early this year and passed away. With each person passing, we lose so many stories and knowledge.

I'm not a First Nations or a cameleer descendant myself. I acknowledge I still don’t know much about their common history, and these projects are my way of learning and sharing. The cameleer descendants have been welcoming to me. At the Sydney Biennale, I worked with two of them who presented their paintings and stories.

As new migrants, we gain a lot from this history. It shows that our presence in Australia has been longer and more beautiful than we thought.