In his four part series for EastEast, the artist and filmmaker Rouzbeh Akhbari is posting brief dispatches from his three-month research trip in Oman. Akhbari’s interest in the region stems from his work on two related projects: research focused on how the International North-South Transit Corridor (INSTC) translates into local contexts near Iran’s maritime and terrestrial border zones, and an experimental documentary titled Point Rendezvou that follows the informal livestock trade between the Caspian and Persian Gulf littorals.

It was originally my conversation with Jeff (the logistics enthusiast with whom I crossed paths next to Sultan Qaboos Port in Muscat) that convinced me to expedite plans to visit Khasab. I expected to move to Musandam, the exclave governorate of Oman next to the strait of Hormuz in the beginning of February, but without getting into details he urged me to go earlier as “the winds of big change are blowing there right now!” I booked a flight for the next day and arrived at Khasab under half-moon conditions right after sunset.

“Winds of change” was but an understatement! From the moment our plane landed, it was obvious that something out of the ordinary was taking place. Besides our aircraft, there was no sign of any commercial activity in the airport. As we disembarked, I noticed a military refueling truck approach the plane. Four attack helicopters were stationed next to the runway and dozens of armed soldiers roamed between the passenger halls. The situation outside the airport was not less tense either. I counted five columns of heavily armored vehicles and personnel patrolling the streets in the distance of three kilometers from the airport to the town’s central roundabout. It was only after greeting my old friends in the city’s notorious Pakistani restaurant and getting deeper into conversation that I realized the reason behind such intense militarization. The relatively new ruler of Oman, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq, was visiting Khasab the next day for the first time since ascending to power.

The following day, we woke up at 5 am to rush to the shoreline and observe the Sultan’s royal yacht. Despite the early arrival, we were already at the end of a large crowd who seemed to have waited at the port all night. The Sultan’s vessel was escorted into harbor by an entourage of merchant and fishing dhowsdhowsTrading vessels primarily used to carry heavy items. , tugs and coastguard gunboats with their crewmen cheering and singing national songs. Although the Sultan only remained in Khasab for 5-6 hours, the unofficial news began leaking only an hour into his visit about the huge amount of investment his central government pledged for the region’s development. As the crowds cheered themselves to exhaustion and the general celebratory ambiance of the city dissipated into the night, the official accounts of the visit appeared on social media. The government announced four major infrastructure projects, all of whom were geared at capitalizing on Khasab's strategic geography and unique ecology:

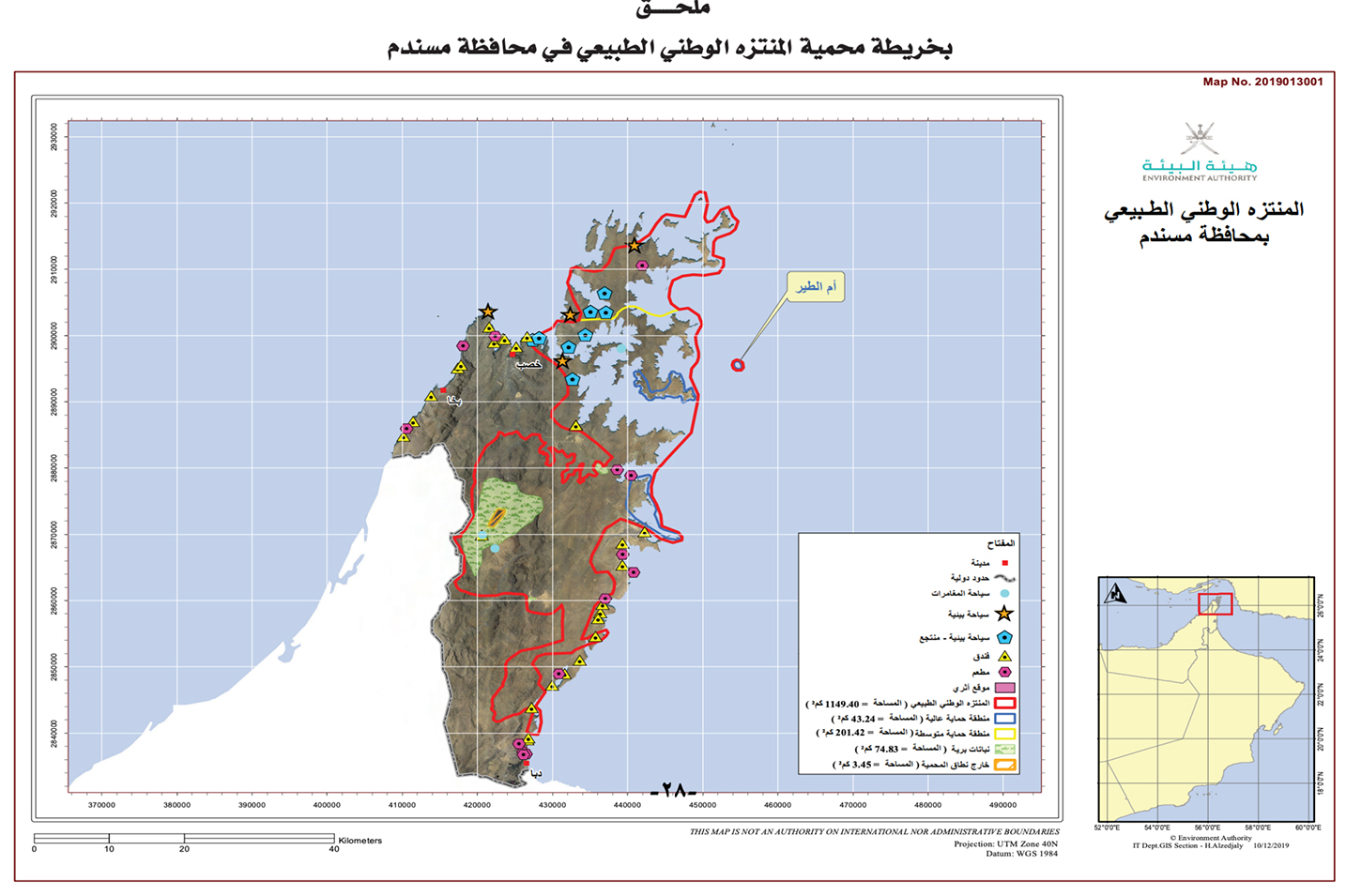

Firstly, the plans to build a brand new airport on the city’s adjacent mountain top, mainly to tackle the operational challenges of the current airfield that is positioned in the middle of a valley. Secondly, the building of a free trade zone and industrial area next to the city’s recently dredged port. Third, the designation of a vast geographical area (nearly two thirds of the entire governorate) into a national park for ecotourism purposes. Lastly and most importantly, the building of a new highway system that acts as a critical corridor between the exclave of Musandam and Oman proper. This road is particularly significant as a political project and an expression of sovereignty that helps bring the governorate closer to the centers of power in Muscat, especially after an increasing number of residents have voiced dissent about the economic disparities between the citizens of Musandam and those surrounding them in the UAE.

Over the next two days, the extraordinary fanfare gave way to an eerie silence. The military equipment was loaded onto cargo planes and ferries destined for bases in mainland Oman, the soldiers returned to their barracks, and local businesses and fishermen resumed their quotidian activities. Despite the general population’s excitement and happiness about the royal visit, one group could not conceal their discontent. Anyone whose occupation directly or indirectly involved international trade—including longshoremen, truck drivers, restaurant owners, and warehouse operators—was rendered temporarily jobless, as the state shut down the international sector of the port for security and aesthetic reasons. The security aspect was readily comprehensible to me, but I later learned that the aesthetic justification had to do with the fact that the main trade at Khasab’s port is conducted informally with Iran and primarily includes livestock, which can smell and appear rather “unroyal.”

After a ten day hiatus, the port opened to incoming watercrafts, replacing Khasab’s ghostly ambiance with the sound of revving speedboats and innumerous trucks that transported sheep between the harbor and the barns on the other end of the city. “The pumping heart of the city,” as the governor refers to the port, had come back to life. On the first day, as hundreds of speedboats delivered the smuggled livestocks that were clogging the supply chains on the Iranian side of the strait of Hormuz, a gigantic luxury cruise liner also appeared on the horizon to flood the city with thousands of European tourists for a few hours

In the first few days of my stay in Khasab, I realized that the story of development in Musandam is nonlinear. The trajectory of “progress” here is in fact a calculated balance of mobility vs blockades. Khasab, not unlike many geographies that undergo rapid neoliberal development, is where excessive militarization and trade meet, where geoeconomic and geopolitical calculations play equal parts in transforming the lives and livelihoods that depend on ancient trade networks.

Over the next two months, I frequented various sites of leisure and commerce (cafes, restaurants, malls, parks, and most importantly, currency exchange enterprises) that play an important role in the social reproduction of the workforce that facilitates the informal trade between Iran and its southern neighbors. In the following dispatches I will get into the details of my observations, but for now, I will conclude this post by quoting a few lines from my field notes. These were recorded during a brief encounter with a sailor who had just arrived aboard a speedboat from Iran after the port had opened following the Sultan’s visit.

[Male| 25-30 | Afghan]

— Is ok with me asking questions, but requests that I do not waste his time as he is in a rush.

— On a good day (meaning no winds or dangerous waves) they make up to three crossings across the strait.

— The pay is decent compared to salaries in Iran. (Does not specify how much)

— His concerns for the dangers involved in maritime smuggling: (looks at me suspiciously) The main danger is the Iranian coastguard. Bribing them usually solves the problem, but not always. Sometimes they shoot to kill. They used to accept cash (USD and local currencies other than Iranian Riyal), but now they only accept gold coins apparently.

— Former career in the Afghan army. Fled Afghanistan to Iran after Taliban’s takeover.

— Ends our brief chat with this sentence: “We used to be Afghanistan’s ground forces. Now we are Iran’s Navy!”