Teresa Yejoo Kim is one of the finalists of the Dream open call we held last fall. In her essay, she talks about the fragile hopes of people living on both sides of the inter-Korean border, especially those of North Korean defectors. We decided to publish it as a thematic bridge between the Dream issue and our upcoming (no)borders issue.

In a time when the terrain of imagination seems to be on the daily verge of collapsing into a void, we are all opting into the realities that we know in order to survive. WeWeBylines traditionally credit a single individual for written work, but anyone who has researched in the field long enough knows their work is deeply indebted to so many. Most of the written labor was produced by me, but any nascent form of knowledge found here was co-produced by my field partners who mostly asked to remain anonymous and generously engage with this work.—All the notes in this text were provided by the author. borrow from our past realities to live through our overbearing present, and what we borrow from the past also informs our creative capacity to dream for the future. Yet, as much as we hope our imagined futures will come true, our hopes more often explain the histories within us rather than the futures that lie ahead.

Hopes and dreamsHopes and dreamsIn this essay, though I have used hopes and dreams interchangeably, I am cognizant also of their varying sociolinguistic registers and how they operate differently and indicate diverse temporal senses in other languages, like Korean. Though significant arguments can be made about these social and linguistic variances, the scope of this essay will not cover them though they are discussed to greater depth in a chapter on my thesis about the temporalities that certain words like dream (kkum) or hope (huimang) entail. provide us with the vitality to move forward. It is human to create affective attachments to our ideal futures in order to live. However, liberalism also disciplines us to revere stories of hopeful resilience, romanticizing the resilience of the most dispossessed of us in uncritical ways. For many, dreams are repeatedly deferred, in conflict with a hungry reality, and even evolve into recurring nightmares. Though this pandemic may have recently revealed the fragility of past hopes and differentiated access to dreams worldwide, many in the communities that I have worked in have been living with their hopes-in-crisis for their entire lives.

North Korean defectors, in particular, have taught me what it means to live and dream through recurrent crises. My initial interests in North Korea were not so much ethnographic as they were rooted in a personal curiosity of what histories existed above the 38th parallel, home to my grandparents and imbued with both transgenerational trauma and recanted past memories. Yet in the “West,” the humanity of North Korea is understood either through bipolar politics of the Cold War or figured through the modern-day disenfranchisement of many who reside north of the 38th parallel. My interviews with North Korean defectors are intended to reach beyond our epistemological infatuation with stories of either extreme disenfranchisement or glossy resilience. Having lived on both sides of the inter-Korean border, they understand both the fissures of socialism and the fiction of democracy. This is significant because it challenges the problematic disenfranchised/resilient binary that has oftentimes been used as a reductive analytic to describe their lives. Furthermore, their lives south of the border help reveal how hopes guide them amidst crises but are also made to vacillate between absence and presenceabsence and presenceIn my graduate thesis, Hopes of the Vanishing: Phantasmagoria and the Politics of Reunification in a Divided Korea (2019), I build upon Marilyn Ivy’s (1995) work on Japanese modernity, where she uses phantasmagoria as an analytical category to understand the nostalgic practices that purposefully stunt and destabilize tradition, by extending the temporal dimensions of this category to study hopeful practices. I posit that the hopes inhabited by the material and embodied lives that I study are phantasmagoric, because while hoping for reunification is encouraged, it is also perpetually disavowed. by tactical, wartime infrastructure.

Deferred Dreams

Of the lives that I follow in Seoul, I attune my focus primarily on two of them. Eun-hye and MinEun-hye and MinAliases were used for my field partners here. were former colleagues of mine who grew to be close friends and acquaintances long before I began my research formally. At the start, we often talked wide-eyed about our dreams and aspirations for the future perhaps because we entered and inhabited our early twenties at around the same time in South Korea. We also shared a liminal, diasporic status in South Korea, them being North Korean defectors and me being a second-generation Korean-American, and this particular commonality, despite the disparities in our material experiences, somehow led us to share our dreams more unapologetically than we would have with our South Korean peers. We tiresomely negotiate and craft our narratives according to our social contexts, especially in unfamiliar ones, so I felt personally relieved to be in the company of those who had complicated relationships to their heritage in an ethnonationalist milieu like South Korea.

Eun-hye (aboveaboveAll pictures or stills from films taken by the author unless otherwise noted.) was in her early twenties when I first met her, and she shared with me over time that she had defected in the early 2000s with her mother, grandmother, and older sister, following the famine years in North Korea (konanŭi haenggun). Her father had defected a few years before them but had lost contact once he arrived in China. Like many who deal with ambiguous loss in their lives, she talked about her missing father with an uncertain kind of sensitivity and care. Understandably, she was keener to talk about her life now and her aspirations as opposed to her life prior to defection. Yet the short, rare moments in which she shared about her life in North Korea told me as much about her as her current life and the kind of life she envisioned for the future.

During the first few years I knew her, she was working towards a diplomatic post in a foreign country to work towards a career in international development. Her ultimate aspiration is to go back to her hometown in North Korea and help culturally bridge to the two Koreas, so she had spent her last few years out of college dutifully preparing (chwijikjunbi) for opportunities abroad to help develop her skills in the hopes that she could return to her hometown once reunification happened. On the day she was scheduled to leave for the post, a South Korean embassy representative met her at the airport, explaining the government had revoked her visa to leave the country. Because the country that would serve as her post for several years has also been the country of transit for North Koreans secretly defecting in the past in recent decades, the representative explained that it would be “unsafe” for her to go. Though the representative utilized the lexicon of governmental protection, everyone—her colleagues, family, and myself—present that day at the airport understood the historical and political treatment of North Korean defectors south of the 38th parallel culminating in that very moment. Eun-hye asked the representative, “Would this be happening to me if I was South Korean?” to which he responded in silence.

Though Min’s aspirations (to establish computer science programs in the North) are not met with as much direct governmental interference as Eun-hye’s, his life aspirations also necessitate reunification in order for them to be enabled. Min’s family (pictured above right ) mainly resides in the North still, and they communicate through brokers and telephone calls once every few weeks. Regular familial contact and the desire to be reunited that emerges from them reinforces North Korean defectors’ personal and career aspirations in South Korea. Nevertheless, their aspirations still remain curtailed by the elusive functions of inter-Korean bureaus and campaigns that fail to signal an outlet to a future in South Korea. In the case of Eun-hye, the South Korean governmental bureaucracy has simultaneously helped curate and repeatedly blocked opportunities for her, noting her North Korean status as the reason for possible inhibitions towards peacekeeping on the peninsula and maintaining her career aspirations and dreams from notable progression. Their freedom can only be exercised within the confines of wartime détente and deterrence. These measures make up a part of the larger, tactical wartime infrastructure of South Korea that, upon closer look, signifies the Korean War is far from over. Their dreams are continually deferred, and their hopes are met with the impasse of the impossibility of the Korean War eventilizing towards an end.

At the 38th Parallel

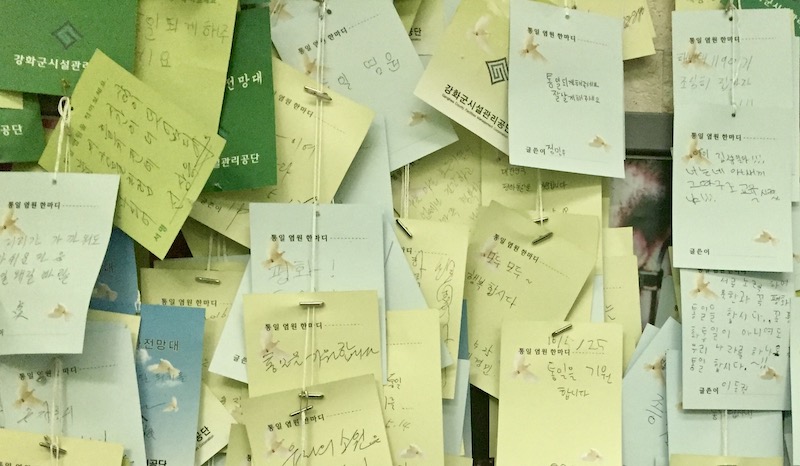

Everyday conversations reveal the structural and bureaucratic frameworks that have regimented themselves into the geography and infrastructures of the Korean peninsula. Ever since the Korean division, both sides of the 38th parallel have participated in a peculiar kind of speculative exercise, that is, “unification preparation.” Yet the peninsula’s inability to move into a post-conflict setting is effectively managed by the political management of hopes for unification. In my research, discussing hopes and speculative futures of unification with my field partners always began and ended with talk of the border. Hopes for reunification that literally hang here at the border (pictured below) occupy a threshold of presence and absence. What does the institution of unification at the dividing 38th parallel really represent then? What future does it signify?

Towards New Openings

“… freedom is precisely the idiom through which liberal empire

acts as an arbiter for all humanityfor all humanityMimi Thi Nguyen. The Gift of Freedom: War, Debt, and Other Refugee Passages, Duke University Press, 2012 (4)..”

My friends’ experiences are punctuated by both the metaphorical border of their divergent political subjectivities and the physical border that signifies their defection stories and inhibits their professional and personal dreams. However, the border and the realities of the DMZ at the 38th Parallel not only affect the dream contents of many North Korean defectors with immediate family members still in the north but those of many South Koreans as well, especially those who live on the South Korean Civilian Control Zone (minganinchuriptongjeguyeok) of the inter-Korean border where the future of agriculture and economic development of the region fluctuate in accordance with geopolitical tremors of the unending war. These experiences are products of the most enduring structural legacies of the “West” and the American military complex, that is, a legacy of family separation and artificial boundaries. These are structural legacies not only generated by ongoing foreign warfare but also domestic disorder. The inter-Korean border, and the district borders that enable voter suppression practices in the United States are products of the same logic of political management under the more palatable guise of a multicultural and democratic order. Intra-ethnic violence at the US-Mexico border and the 38th parallel reveal the price that dispossessed people pay for social mobility—complicity with the American military and policecomplicity with the American military and policeSee Simeon Man’s (2018) monograph, Soldiering through Empire: Race and the Making of the Decolonizing Pacific, on how the US empire was sustained through colonizing and race-making projects. For South Korea, military labor was sent in large numbers of soldiers to the war in Vietnam. What is clear from these entanglements is that economic prosperity and influence was bought through the promise of US military aid, offshore contracts, and the heavy price of civilian and military casualties.. These lines of geographic demarcation on paper further regimented themselves over time to unequally distribute freedom and geopolitically disrupt decolonizing processes around the world.* This is acutely true for the United States and how its “invisible empire” geographically asserts itself around the world on the 38th parallel and beyond.

However, what eases my cynicism currently are the recent, sometimes inadvertent, bases for global solidarity that have emerged against the police and US military in the wake of generations of structural violence made more visible in just the last year alone. Borders make the irony of “Pax Americana” painfully evident. Peace is wedded to violence. Dreams are deferred by an unending war. Unity lives through division. All to say, democratic sovereignty is rife with paradoxes. The public awareness of such paradoxes has only been exacerbated, I believe, in a COVID-19 era, but they have shaped the contents and deferred the hopes for many others for a very long time. I present their stories not as points of inspiration but of points of global solidarity for artistic, academic, and public interrogations of border logic. Dreams are beginning to materialize into a field of real solidarities and radical possibilities. If these are some of the byproducts of living through this extended crisis and impasse, then perhaps it is not too naïve to believe in a better, more livable world soon.

On a concluding note, I share a series of photos from a civic art program that other colleagues and I helped organize in 2018 and we invited North Korean defector adults to share their artistic interpretations of “home” and “hometown.”

One of our participants, Hyang, published a photo-journal of a series of gatesa series of gatesMany traditional homes in South Korea have locked gates at the front though many of these homes are disappearing with the construction of towering apartment buildings in most cities. (dae-mun), explaining that resettling in South Korea for her meant adjusting to the closed gates and doors that secured most homes. In her North Korean childhood, neighboring families entered each other’s homes quite freely, bringing food and convivial conversation with them. Despite the austerity of socialist measures in North Korea (strict curfews, scarcity of food, lack of basic amenities, etc.), families often shared their possessions with each other to survive, and the open doors of her neighbors’ homes paint the memories of her youth. The photos were taken on Jeju Island, where she currently lived at the time, and they reveal a progression of closed to open doors as a photographic and metaphoric expression of her feelings towards life outside of North Korea, dreaming and believing the warmth of her childhood could be revived again in a borderless future to come in our lifetime.

“It is a new society that we must create, with the help of all our brother slaves, a society rich with all the productive power of modern times, warm with all the fraternity of olden daysolden daysAimé Césaire. Discourse on Colonialism, Monthly Review Press, 1972 (52)..”

* Kuan-Hsing Chen’s Asia as Method (2010) writes lucidly about this: “The former empires have not actively thought through the history of their imperialism and hence could not respond properly to the living historical issues in the former colonies. Consequently, decolonization and deimperialization movements could not successfully advance in the third world, and they were unable to build enough momentum to drive the former imperial powers to take on the historical responsibility of self-reflection. This seems to be a hopeless, self-perpetuating loop, but we must recognize that, in contrast to the former empires, the third world has developed a tradition of large-scale decolonization movements, which can be mobilized to drive the next round of deimperialization” (200).