Pedro Paulo Palazzo / flickr.com/arqpalazzo

Ibraaz is one of the leading publications on visual culture in North Africa and the Western Asia. In 2013, it featured an essay by Walter Mignolo in which the famous researcher described what they see as the possibilities for the decolonization of the Western museums using institutions in Qatar and Singapore as examples. We decided to republish and translate this important text as part of our new issue, which explores the various meanings of access and accessibility and is focused on collaboration with various organizations in the MENA region and beyond.

I

“The Danger of a Single Story” is a celebrated speech by Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, in which Adichie talks about stories and how they matter. Adichie's main point is that a single story, once released into the public domain, becomes a hegemonic one. The power of a single story is that it can make us believe that the world is as the story tells it, without questioning the authors who are constructing the narrative. It is the kind of story that transcends the status of “fictional narrative” and becomes ontology—or “reality” in common parlance. I am starting with this reference to Adichie in an essay focusing on the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Asian Civilizations Museum in Singapore, because I will be looking at the museum as a story and as a space of narrativespace of narrativeMy argument here is a continuation of the article published for Ibraaz Platform 005 on the occasion of Sharjah Biennial 11 (2013) and a response to Ibraaz Platform 006..

Here, it is important to consider the single story of the museum as a Western construct and to note how both modernity and tradition are concepts of European narratives. The idea and the concept of “modernity” is one example of a single story that has long held the power of maligning and disavowing anything deemed “un-modern” according to the actors and institutions defining what modernity is or should be. At the same time, we must also bear in mind that European narratives of modernity were built in contrast to tradition. “Tradition” is not an ontological moment in human history. When thinking about various museums in the Western world, such as the British Museum, one could argue that there is either a European “tradition” (Greek Antiquity and the Latin Middle Ages, for instance) or many “traditions” that come from non-European societies, which are often seen—and described—from European perspectives.

Indeed, Western “representation” in their own museums of cultures other than their own, has long been a contentious issue when thinking about the institution. But in the later twentieth century and the emerging twenty-first century, the economic boom in East Asia and the Middle East has brought about confidence and urban exuberance. Visiting Shanghai or Doha, it becomes clear that according to European narratives of modernity, modernity itself is no longer in Europe. From Hong Kong, Shanghai and Singapore to Paris, London or Berlin, it is evident that Europe has become the “tradition” of its own concept of modernity—Doha and Kuala Lumpur today are what Manchester was in the second half of the nineteenth century.

In this light, this essay will seek to explore the rise of a multi-polar world order and unravel the many stories from the period of Westernization, imperialism, colonization, and “Eastern hegemony to the era of de-Westernization and de-coloniality. I will look at how the Western museum model is being appropriated and used for the resurgence and reemergence of civilizational stories that have been disavowed and arrogated by the very museum model being usedbeing usedAs above.. Reading through the Museum of Islamic Art and of Asian Civilizations Museum, I will be following in Adichie's footsteps: in this case, attempting to decolonize the single story of Western museums by showing how de-Westernization workshow de-Westernization worksWalter Mignolo, “How De-westernization Works,” Walter Mignolo website, 20 July 2013.

. That is, my own argument will be the de-colonial story of Western museums through the appropriation of the museum model in the Global South and the Global East.

Pedro Paulo Palazzo / flickr.com/arqpalazzo; Kuang Chen / flickr.com/kuangc; Thomas Galvez / flickr.com/togawanderings

II

The Greek word museion means “place of study” and was translated into Latin as museum—that is, a library or a place of study. The word comes from the Greek word “muse,” used to describe the seven daughters (the seven muses) of Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory. This kind of reverence towards the museum space, as a place of learning, was instrumental in building the profile and identity of Western civilization as we know it today. Museums were the places where the Western archive was enacted, organized, and exposed—houses of knowledge. Western museums were also the place to collect and organize artifacts of the non-European world—collected artifacts, but not the memories of the people from where the artifacts were removed (either by looting or purchase). Thus, museums as they evolved in the modernizing, Western world, enacted the archive of Western civilization but could not enact the archives of the rest of the world. In this sense, the museum could only collect artifacts representative of “other” memories, but not enact the memories contained in those removed artifacts, displaced from their cultural environment, their owners, and authors.

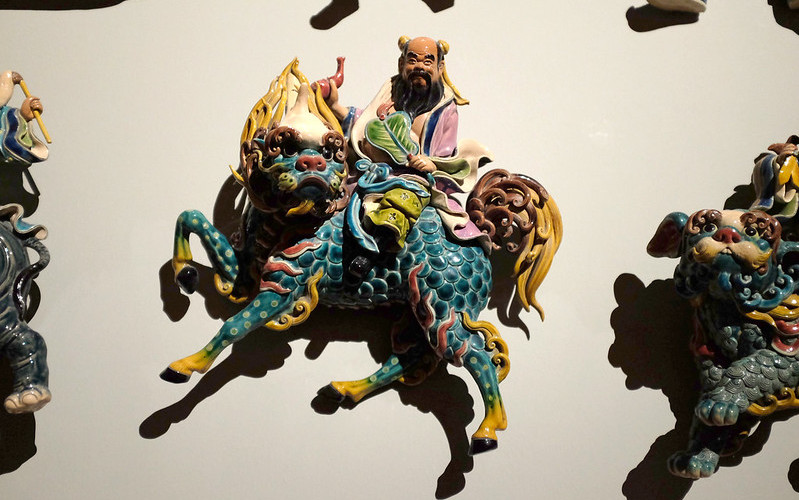

The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha's magnificent building is identified from a distance by its fortress-like walls, the color of which both blends with and enhances the desert sand. Its form is a series of clear and angular lines, produced by a series of cubes that create the fragmented pyramidal shape of the building. Built on a peninsula, the edifice is surrounded by water and from inside the museum, the visitor can admire from the building's immense glass windows, the eye-boggling architecture of Doha and the city's array of downtown buildings. From here, boats look like children's toys and helicopters like mosquitoes

A critical and inquisitive mind would wonder at this point how it is that a museum designed by a team led by a Chinese-American architect, I. M. PeiI. M. PeiMark Hudson, “Museum of Islamic Art in Doha: ‘It's about creating an audience for art,’” The Telegraph, 20 March 2013. and French interior designer Jean-Michel Wilmotte, might be considered an act of de-Westernizationact of de-WesternizationClicknetherfield, “Museum Display Cases at Museum of Islamic Art Doha,” online video clip, YouTube, 19 August 2010.

. Questions begin at this point: how can we consider a museum that replicates the idea of the Western museum to be a de-Westernizing project? And furthermore, how can one ignore the critique that such a project is nothing more than an exuberant showcase of Arab capitalism, appropriating Islamic art to project an enhanced image of the state? These are all legitimate questions and the answer could be this: in the same way that the museum was a crucial institution that built the idea and image of capitalist Western states and civilization, so the museum as an institution is being appropriated and implemented outside of the Western world to enact derogated archives, memories, and identities.

In many ways, one might say that the process of de-Westernization is at the point of no-return and it is building itself on an entangled inversion. However, it is not a question of binary oppositions but of entangled power differentials. While major Western museums were built by collecting artifacts from around the world, the rest of the world was being collected and “represented” in London, Berlin, or Paris. In that regard, there is no equivalent of ethnographic and ethnological museums in the non-Western world because Western Europeans and Anglo-American cultures are not an object of study for anthropologists of South East Asia or the Middle East, for example:”'knowledge” was located in “Western Civilization” and “culture” in the rest of the worldrest of the worldLooting began much before the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It began in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in the New World. For a detailed account see Michael D. Coe, Breaking the Maya Code, London: Thames and Hudson, 1999..

Yet today, there does seem to be a trend in the non-Eastern world towards collecting not Western ethnographic artifacts but rather, modern and contemporary art masterpieces and “minds.” Most of the time, these minds are the people who are put to work so as to implement a certain design for global intervention—Western architects and interior designers for example, employed to design grand museum projects according to local visions (for example, the hiring of Pei and Wilmotte to build Doha's Museum of Islamic Art, or curators from abroad invited to assist in what is essentially a trade in knowledge from one culture to another, such as Yuko Hasegawa curating the 11th Sharjah Biennial). In every case, however, these “cultural minds” are employed and paid to do what has been requested.

Gilbert Sopakuwa / flickr.com/g-rtm; Bradjward / flickr.com/bradjward; Ciphers / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

Of course, the Museum of Islamic Art is a powerful statement, questionable for some and celebrated by others, but it is a statement without a doubt. Questions around the museum come, however, from very questionable assumptions. You do not have to be a defender of the project or a Sherlock Holmes disciple to realize the shaky grounds of such critical assumptions. One such assumption is that the Museum of Islamic Art is an extravaganza made possible by the incredible amount of currency in Qatar right now. We shall keep in mind here the investments that have been made by the nation, both in terms of the development of its own state cultural institutions and in terms of the investments Qatar has made internationally, from the sponsorship of a major Damien Hirst retrospective at Tate Modern, which was later shown at the Qatar Museums Authority in 2013, to the purchasing of major works of Western art at auction.

In the case of Qatar, financial investments in contemporary art look like an extravaganza to (jealous?) Western eyes, it is not as extravagant or as ostentatious as it may seem if we are to put this into perspective. Perhaps we should remember the extravaganza that went on in the seventeenth century, when the 70,000 pieces collected by Sir Hans Sloane provided the foundations for the British MuseumBritish Museum“Sir Hans Sloane,” The British Museum website., not to mention the hereditary monarchies that built The LouvreThe Louvre“History of the Louvre: From Château to Museum,” The Louvre website.

in Paris. To fill up the British Museum and The Louvre in their respective times was a prerogative of monarchs. Thus, in thinking about how the British and French monarchies built their own image of power, wealth, and taste through their art collections and their museums, what is so wrong with the monarchies of Qatar or the Emirates today building museums for the same reasons?

But of course, it is impossible to ignore the rate with which cultural museums and collections have been growing outside of the West in the twenty-first century. Compare the budgets of the Museum of Modern Art in New York at $32 million a year to the Metropolitan Museum's budget at $30 million a year, with the budget of the Islamic Museum of Art in Doha, which is $1 billion a year. That fancy amount allowed Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani to dispense of $250 million for Cezanne's Card Players (1890-1895), about six times the budget of each of the two New York Museums just mentioned combined in 20122012Alexandra Peers, “Qatar Purchases Cézanne's The Card Players for More Than $250 Million, Highest Price Ever for a Work of Art,” Vanity Fair, 2 February 2012. . Sheikha Al-Mayassa, sister of the recently appointed Emir of Qatar, chairs the Qatar Museums Authority (QMA), which oversees the running of the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA), Mathaf: the Arab Museum of Modern Art, and the under-construction National Museum of Qatar (NMoQ). She enjoys the handsome acquisition budget of $1 billion a year$1 billion a yearRobin Progrebin, “Qatar Redrawing the Art Scene,” Gulf News, 27 July 2013: “With an annual acquisition budget of $1 billion a year, Shaikha Al Mayassa is creating a first class contemporary collection.”

. Why that budget? Well, firstly because the fortune of the emirate of Qatar allows a small percentage of annual revenues to fund Qatar's museums and arts. But why is that money not used to end poverty or to social justice? It is a good question, which might then lead us to ask why the USA has the largest military budget in the world, with an obscene amount, recently revealed, dedicated to cyber espionage.

Why indeed that budget for art in Qatar, as the European Union and the United States cut their museums, art, and education budgets in favor of “efficient” education that prepares youngsters to “compete” in the competitive world of the future? No time for art, of course. But this is not the point. The point is that Europe and the USA do not need to spend extravagant amounts of money to build their own civilizational identities because they already did so. Europe started in the Renaissance; the USA, since the early twentieth century.

Ben / flickr.com/gumber

As such, Qatar is responding to the needs of the time. Whether we like it or not, it is a vision and it is a necessary vision. Sheika Al Mayassa once said in a Ted Talk in 2010 that: “We are revising ourselves through our cultural institutions and cultural developmentcultural developmentI won't hesitate to say that her TED talk brilliantly articulated what de-Westernization in the sphere of art and museums means: “Sheikha Al Mayassa: Globalizing the local, localizing the global," TED website, February 2012..” She added that art becomes a very important part of national identity. In an interview with The New York Times, she also noted how establishing an art institution could also challenge Western preconceptions of Muslim societiesMuslim societiesRobin Pogrebin, “Qatari Riches Are Buying Art World Influence,” The New York Times, 22 July 2013.

. The point here, whether you agree with it or not, is that these cultural-ideological shifts happening in the non-Western world are taking place parallel to the confidence provided by growing economies in East and West Asia (also called the Middle East in Western orientalist vocabulary). Furthermore, these shifts are part of a larger and complex de-Westernizing move.

Take the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and its envious budget to acquire artworks as well as to invest in and promote art in the region. The investment here is, in many respects, a way to regain a sense of pride in an identity. Yet, a critique could be made that, given the increasing global imbalance between wealth and poverty, such budgets devoted to art acquisition, as seen in Qatar for instance, makes the disparity between the rich and poor more visible. Nevertheless, if we are to compare the QMA's acquisition budget with that of the USA's military expenses, with its yearly budget of $662 billion a year, we might gain a different perspective. To further this, consider that China is in second place when it comes to military expenditure, at $162 billion a year contributing to the grand total of $314.9 billion a year for Asia; Saudi Arabia is in seventh place, at $57.6 billion a year, contributing to the $166 billion a year for Middle East and North AfricaMiddle East and North AfricaLaicie Heely, “U.S. Defense Spending vs. Global Defense Spending,” The Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation website, 24 April 2013..

Now, if you are a Muslim, you might feel angry by the fact that “Islamic art” is being exhibited in The Louvre. Conversely, you might feel proud if, instead of The Louvre, you were to view Islamic art in the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha. But if you are of a critical mind, Muslim or not, you might denounce what lies behind the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha: the money of global capitalism in a small and non-democratic state ruled by a dynastic family. Yet, in the case of Qatar, the wealth that has fed into the construction and development of the Museum of Islamic Art comes from the same place as the the “antiquities” that can be found in three major Western museums—the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, the British Museum, and The Louvre—that is, the non-European world. Of course, the only difference is that in these three institutional cases it was not only the old European monarchies that contributed to the establishment of such institutions of cultural memory. Much of the accumulated wealth and capital in the last three centuries, which saw the birth and evolution of these institutions, came also from the secular and democratic bourgeoisie, who extended the tentacles of imperial Europe all over the world, mainly via Britain and French colonialism and particularly since 1875 and 1878, when archaeological and anthropological investigations in North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia ran parallel to economic and political European expansionEuropean expansion“History of the Louvre: From Château to Museum,” The Louvre website..

For example, The Louvre as we know it today was inaugurated in August of 1793, one year after the establishment of France's First Republic in 1792—a symbol of a burgeoning French nation-state. Yet, it would later house Egyptian, Near Eastern, and Islamic treasures that were “imported” and exhibited. The building itself has a long history, but what comprises its current form is due to Francois I, who began a project of transforming the Tuileries palace in accordance to Renaissance architectural and design trends in 1546. Under the reign of Henri II, the Hall of The Caryatids and the Pavillon du Roi (King's Pavillion) were constructed and included the king's private quartersking's private quartersIbid.. The complex was again radically transformed after the French Revolution of 1789 and became a place to gather monuments of the sciences and arts—that is, a place of memory and learning: a museum. It was clear, however, in the mind of any European of the time, that the sciences and arts were a trademark of Europe and of Western civilization.

Thus it should not be surprising that today the economic wealth in Western Asia has aided a trend for cultural re-emergencescultural re-emergences“Cultural resurgence” is also a key word behind the epistemic, ethic, and political self-affirmation of First Nations in Canada, Native Americans in the USA and Pueblos Originarios in South and Central America. Resurgence is being enacted by elites of wealthy states as well as by people without a state. outside of the Western world. In the case of the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha (and in general, the QMA), I find a healthy mutation in relation to Western imperial management of world cultures. It points toward a multipolar approach to economy and international relations and a move to a pluriversal world perspective that is emerging in the sphere of art and ideas. Museums of arts and of civilizations of this magnitude have been made possible by exuberant and autonomous economic growth in the postcolonial regions that has taken place since the end of Western imperial rule, and within the context of newly-established sovereign monarchic states. It is growth that, for many, was not supposed to happen, especially without the help of Western institutions. What is more, what is happening is not merely an imitation of Westernization, but an enactment of de-Westernization in that Western cultural standards are being appropriated and adapted to local or regional sensibilities, needs, and visions. In the sphere of civilizations and museums, this is a significant departure.

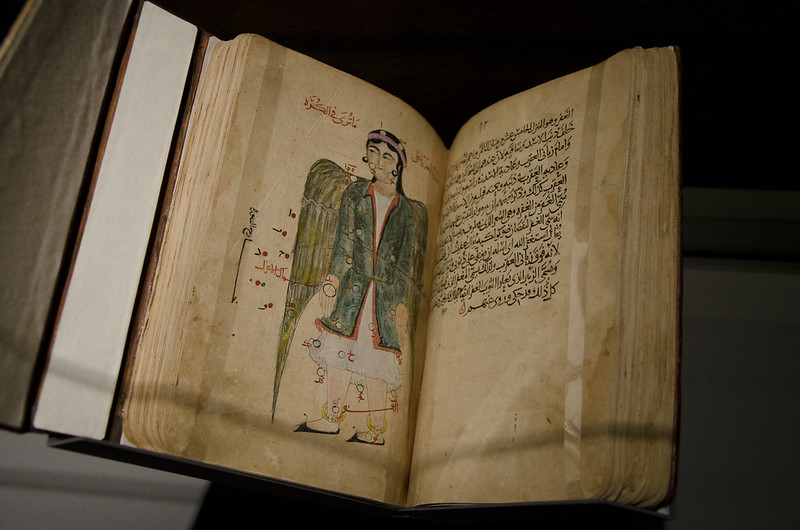

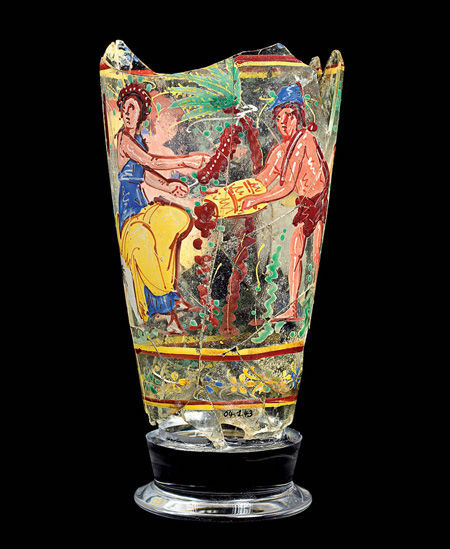

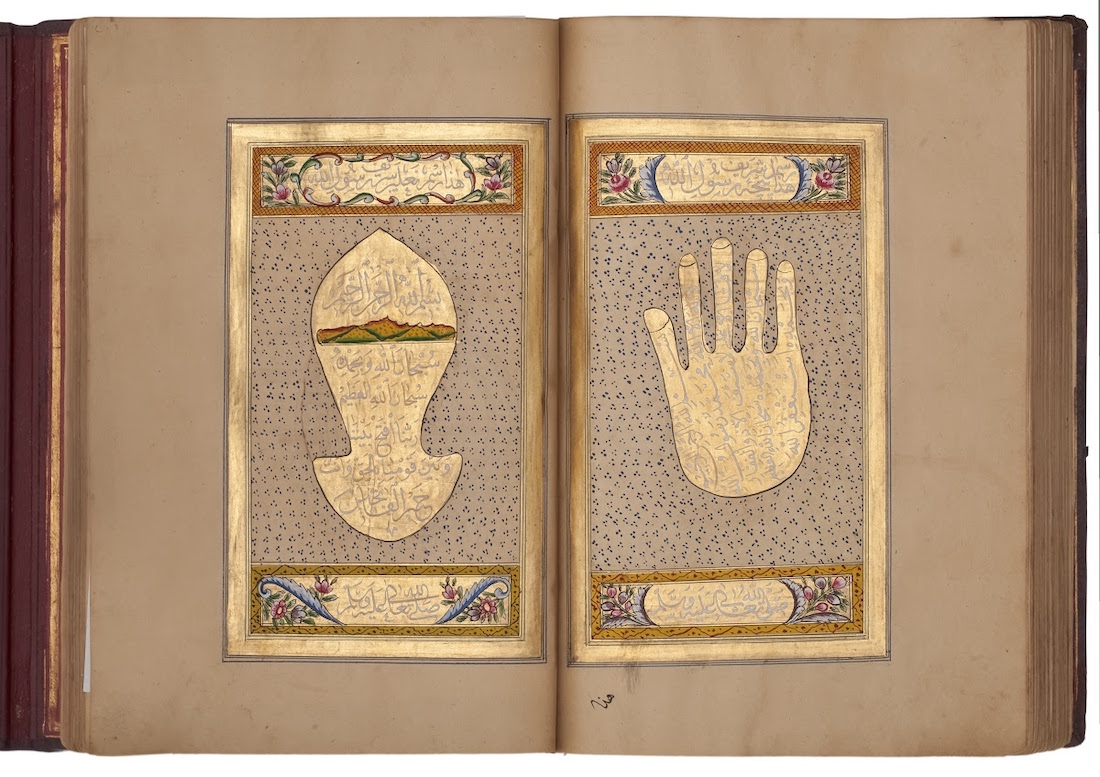

MS.399.2007 / The Museum of Islamic Art, Doha

III

Let us pause to consider how the history of Western museums has been built on two premises. The first was to lay out the foundations for Western civilization's identity and to consolidate, since the nineteenth century, the national culture of the three main European nation-states to come out of the Enlightenment period: England, France, and Germany. The second premise was to lay out the imperial identity of these three countries through the following museums: the British Museum, the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, and The Louvre in Paris.

Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753) was a British collector. During the span of his life he was reported as having collected about 70,000 artifacts—mainly books, manuscripts, and antiquities (basically Greek and Roman). The British Museum was inaugurated in June of 1753, thanks to Sir Hans Sloane's collection. Known as a museum of human history and culture, its foundation and growth coincided with the greatest period of British imperialism, with the museum aiming to house the memory and cultures of the world.

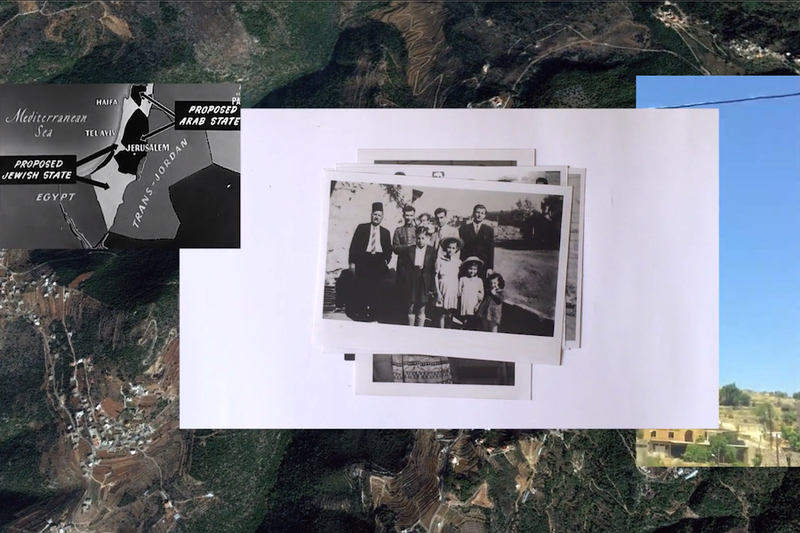

But in thinking about the Greek origins of the word “museum” and the fixation the Western world has had on its own roots in classical Greek culture, the story of the museum itself shall not remain limited to the legacies of Greek memories today. After all, memories are multiple and plural, and not every memory emanates from Greek—or Western—fountains. In this light, what projects like the Museum of Islamic Art and Asian Civilizations Museums are doing is institutionalizing the memories of their own civilizations after having endured the loss of their cultural memories and legacies through the loss of their artifacts. In this scenario, it is only a question of time until actors and institutions whose identities and memories have been stolen (“stolen memories” is how a Kichwa speaker from Ecuador described “coloniality” in his own language, which was then translated into Spanish as memoria robada) would expand, continuing a long journey of recovery.

The Asian Civilizations Museum was built under the same premises of building on stolen memoriesstolen memories“About Us,” Asian Civilisations Museum website.. While every Asiatic person may be proud or angered to have their memories exhibited in the Berlin Ethnological Museum or in the British Museum, it would be another story if the pillars and the traces of Asian civilizations were being collected, recovered, and rebuilt in Asia instead of Europe. If you are of a critical mind, you can also argue that Singapore is a capitalist country and its democracy is suspect. If that is your argument, I would also invite you to think about the suspect democracies of the nation-states that each built the noted museums discussed above in London, Berlin, and Paris, not only by accumulating and celebrating their own past, but also by buying or looting the memories of non-European civilizations.

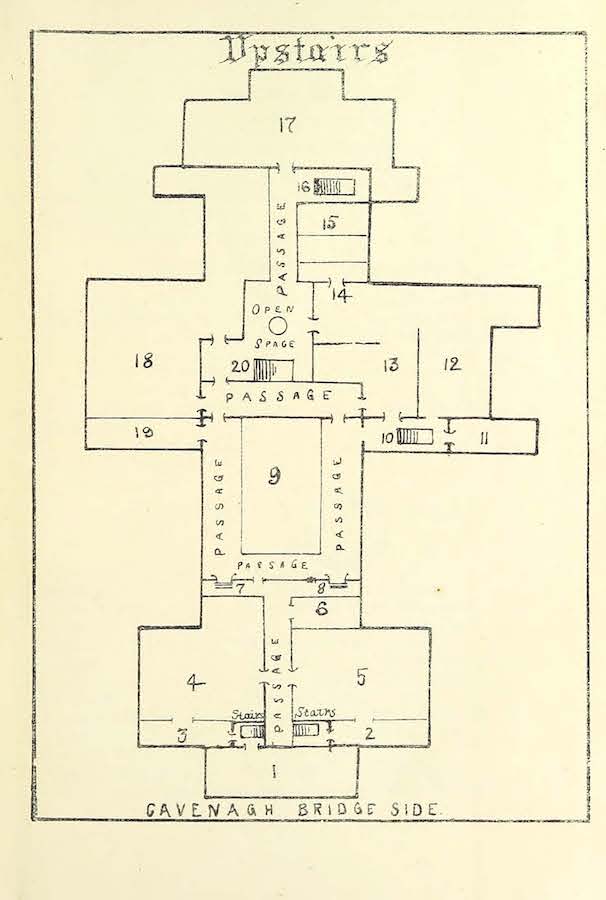

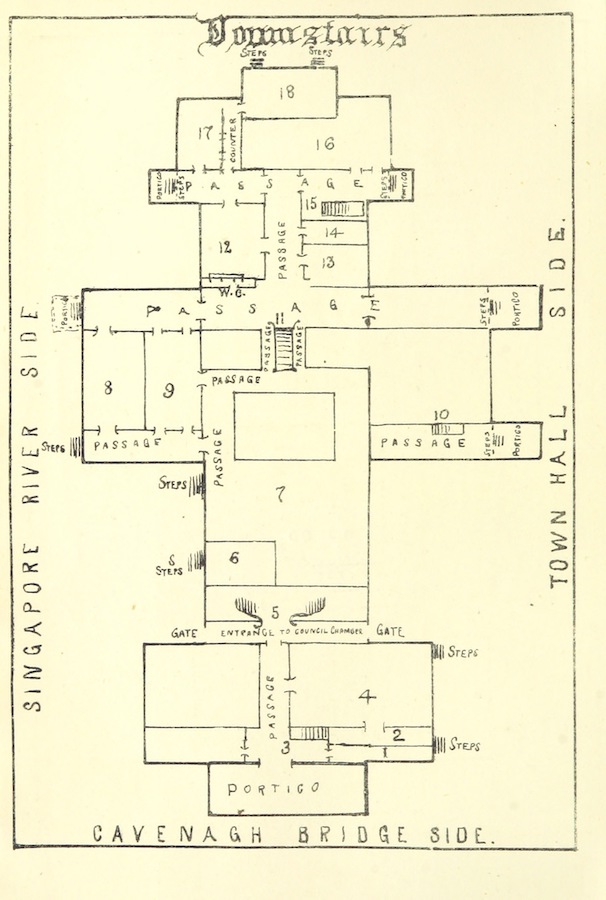

Bottom: Government Offices in Singapore blueprints, 1890

Jacklee / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0

British Library

In a reversal or recuperation of such a legacy, the Asian Civilizations Museums in Singapore is building and enacting the archive of Western civilization: the part about the accumulation of meaning and the accumulation of money, two complementary dimensions of European imperial expansion. As a physical reflection of this, the state of Singapore did not hire architects located in the West to build their museum, but instead occupied the original building of the British administration located at the newly-restored Empress Place BuildingEmpress Place Building“Image of the Asian Civilisations Museum building,” Wikimedia.—Government offices during the colonial era. What this means is that the museum, in the context of its location, assumes and surmounts British colonial legaciesBritish colonial legaciesHengcc, “Asian civilisations museum of Singapore—Art of lacquer from China,” online video clip, YouTube, 17 June 2013.

. Because the state of Singapore has appropriated a building that carries the memory of the British Empire and has translated it into the memories of Asian civilizations, it also acknowledges and reflects on the colonial memories that also feed into Singapore's cultural memories. But this is not “stolen memories” in reverse, if you compare it with what European museums did. Rather, it is a recovery of precisely those stolen memories into the historical narrative of Asia: rather than “being told” the single and all-encompassing narrative of Western civilizations caged in Western museums, the Asian Civilizations Museum opted to tell the story themselves. Thus, while in European museums we often face stolen memories, in the case of the Asian Civilizations Museum, we see through the museum's appropriation of a former colonial building in Singapore, a nation enacting its own archive.

Take, for instance, a statement on the webpage of the Asian Civilizations Museum, which explains that the museum's aim is:

To explore and present the cultures and civilizations of Asia, so as to promote awareness and appreciation of the ancestral cultures of Singaporeans and their links to Southeast Asia and the world.

It is highlighted as the first museum of pan-Asian civilization in the region. The museum draws attention to both the national-state image and the forefathers' pan-Asian visionpan-Asian visionSven Saaler and Christopher W. Szpilman, eds., Pan Asianism: A Documentary History, Volume 1: 1850-1920 (New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2011).. It is underlined in the historical documents, artifacts, and literature from the past 200 years, when Singapore's forefathers came to settle in Singapore from many parts of Asia. The cultures brought to Singapore by these different people are intricate, complex, and ancient, and it is ultimately this aspect of Singapore's history that is the focus of the Asian Civilizations Museum. Its collection therefore centers on the material cultures of the different groups originating from China, Southeast Asia, South Asia and West Asia.

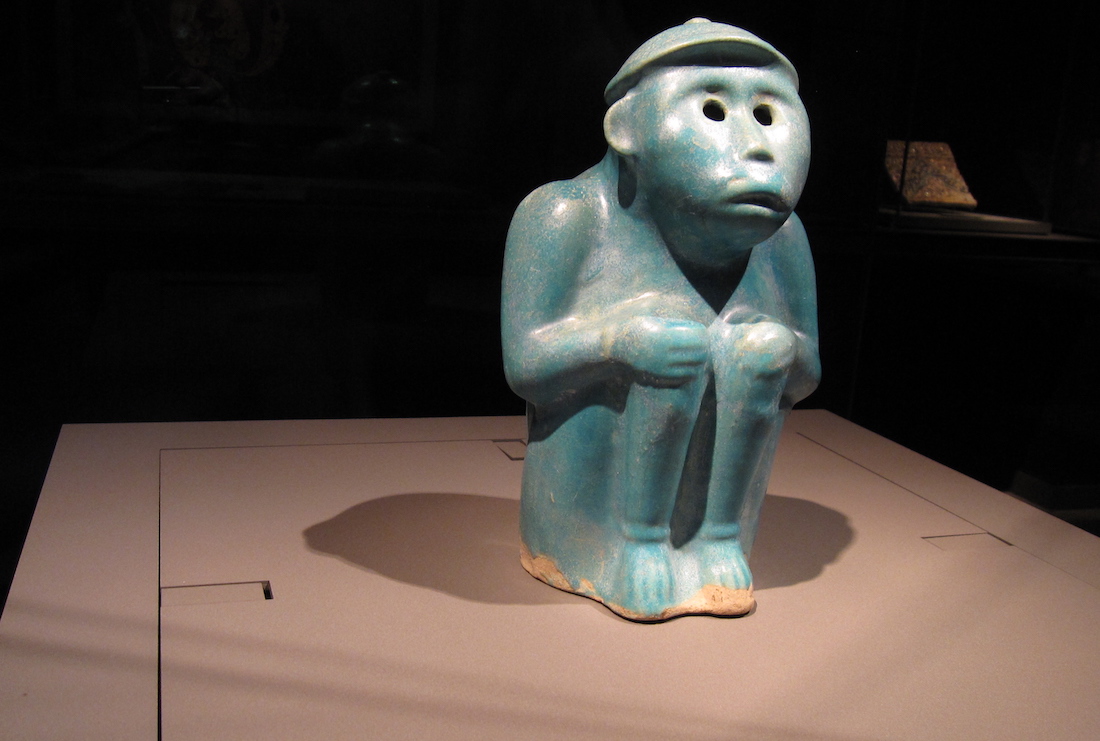

Indeed, the curators of the Asian Civilizations Museum's permanent exhibition are neither oblivious to the British past in Singapore's history (the British settled on the island in 1819), nor to the Japanese invasion during World War II. The permanent collection includes Chinese fine Dehua porcelain figures, calligraphy, and a decorative sanctuary from Buddhism and Taoism. The exhibition also includes Chola bronze sculptures of Uma—Shiva's and Somaskand's consorts—from South Asia. From Southeast Asia, the permanent collection deploys a wide spectrum of technological material, such as Javanese temples, Peranakan gold and textiles, Khmer sculptures, and so on. There are also spaces for temporary exhibits that complement and enlarge the permanent collection enacting the archive of Asian civilizations here.

But of course, the Asian Civilizations Museum is not a “national” museum; it is a civilizations museumcivilizations museumIt shall be mentioned in this context also the Doha and Sharjah Museums of Islamic Civilizations. Both are contributing to shifting the politics of cultural geographies in a multipolar world connected by a common type of economy, capitalism.. It could be taken as such and, consequently, it could be lined up with several “third-world” museums that were built to honor national memories, such as the Museo Nacional de Antropología located in Mexico City. This museum has been highly praised for its monumentality and the celebration of Aztec civilization. But it has also been harshly criticized for appropriating a civilization to which none of the state actors who built the museum belonged —none of them of Aztec descent but rather Spanish descent (mainly, and mestizos). Thus, the creole and mestizo, as elite of European descent in Mexico, “stole” the memories of Aztec civilization and framed it in the narrative of their nation while continuing to marginalize indigenous peoples of Aztec descent. On the contrary, in Singapore, builders of the Asian Civilizations Museum were indigenous (not of European descent, like in Mexico) just as the builders of the British Museum and The Louvre were indigenous peoples of England and France.

But I do not intend to play Singapore against Mexico here. Simply, I note significant differences between the Asian Civilization Museum and the Museo Nacional de Antropología, only to understand how, in different local histories, re-inscribing the past in the present is a question of dignity and cultural survival. In the end, the celebration of Singaporean and Asian heritages in the Asian Civilizations Museum is a necessary correction to the Western historical disavowal of “other” civilizations.

flickr.com/surveying

IV

I have been suggesting that both the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore are two projects, and no doubt we will see more in the near future, with very clear intentions. One direction points to the rebuilding of civilizations affected by 500 years of epistemic, religious, and aesthetic hegemony located in the periphery of the Greco-Roman tradition of Western civilization. The other aims to delink from the tyranny of the historical Western accumulation of meaning through the theft of memories contained in the form of archival artifacts. When making this claim, I have been confronted with criticism, some already mentioned. Another criticism is that both the museums I discuss here—the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Asian Civilization Museum in Singapore are nothing more than state propaganda. I agree. They are propaganda inasmuch as the British Museum, The Louvre, and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin are also instruments of propaganda. All these museums have double goals and visions. The difference is that only Western museums have fractured the memories of non-Western civilizations by depriving them of their cultural and historical heritage.

Looking at the stories and the histories of collecting by the three Western museums I have mentioned in this essay, The Louvre, the Ethnological Museum in Berlin and the British Museum, you will understand that what is exhibited there reached Europe through travellers and officers of the empire, who took advantage of their privileged positions in the colonies. Stories abound. One example is a piece stolen from Afghanistan and exhibited in the British MuseumBritish Museum“‘Beautiful and priceless’ ancient treasures stolen from Afghanistan on show at British Museum,” The Daily Mail, 2 March 2011. and the second example, from another museum, is the entire Niño Korin collection in the Museum of World Culture in Göteborg, Sweden, which ended up in the Göteborg Museum of Ethnography (now Museum of World Cultures) following a visit by its then Director, Henry Wassén to La Paz in 1970 for the International Americanist Congress in Lima. After participating in the congress in Peru he went to Bolivia, and there he saw an interesting collection at the Archaeological Museum in La Paz. It is assumed that he paid $1,000 for the collection. In 2009, I participated in writing a report at the moment in which the Bolivian government was requesting the repatriation of the collectionrepatriation of the collectionW.D. Mignolo, The Power of Labeling, ed. Adriana Muñoz, Report for the Museum of World Culture (Göteborg: Museum of World Culture, 2009).

. This conflict does not appear to be a problem for the Asian Civilization Museum or for the Museum of Islamic Art, suggesting an almost liberating kind of autonomy when it comes to the freedom with which these two institutions are building, or rebuilding their own cultural heritage and their historical memory in the process.

04.1.48, 04.40.50, 04.1.43, 04.40.109 / National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul

The Asian Civilizations Museum in Singapore and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha practice a different politics towards “stealing” Western memories. They steal the mind of a Western architect (Doha) or they take advantage of the building that has been left by the British colonizer in Singapore. The power differential established through 500 years of dominance by Western civilization was at the same time the triumph of a master narrative that created the fiction of “modernity” and presented it as a universal history, with Europe at the center of that unfolding.

The task ahead is to undo that fiction and to reduce Western civilization to size: the most recent civilization in the history of humankind, and the only one that was able to integrate and devalue all other civilizations on the globe. That era is ending. De-Westernization is one road to the future. The Museum of Islamic Art in Doha and the Asian Civilizations Museum in Singapore are two initiatives in this direction. They were both built on the globalization of capitalism, in the same way that European museums were built on the rise of European capitalism and imperial expansion.

But one final note of caution: given the vibrant artistic responses from all over the Maghreb to North Africa to the Middle East and beyond, both museums discussed in this essay could easily be dismissed as state projects founded on economic wealth; the antithesis of any kind of popular reclamation of cultural autonomy. Certainly, none of the two museums I have discussed are emerging from grassroots vibrancy. Yet, civilizational museum building takes place parallel to the struggles for economic and political autonomy (auto-nomos). The de-colonial venues outlined in this essay run in parallel with, and are akin to, the grassroots work currently being carried out through art practices and artistic management not only in Maghreb, North Africa, and Eastern Asia; but also among “Black Europe's artists and curatorsBlack Europe's artists and curatorsAlanna Lockward, “Black Europe Body Politics: Towards an Afropean Decolonial Aesthetics,” Social Text: Periscope, 15 July 2013..” These venues work on de-colonial trajectories and, in simple terms: civilization museums can and do work on de-Westernizing trajectories.

Yet, this is not a “clash of civilizations.” Certainly both the Museum of Islamic Art and The Asian Civilizations Museum are both state projects. But, and I repeat, so are the British Museum, the Louvre, and the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. None of them are museums of the people, by the people, for the people. All of them are state museums that function on two levels: the first is the mediation of inter-state cultural politics and the second is the education, according to state vision, of nationals as well as for foreigners and tourists, of a country's established historical and cultural narrative. If one fails to understand de-Westernization because de-Westernization is not enacting the archives in the way they should, one may end up glorifying the Asian collections in the British Museum or celebrating the Islamic art collection in The Louvre while condemning the Asia Civilizations Museum in Singapore and the Museum of Islamic Art in DohaMuseum of Islamic Art in DohaInformation about unacceptable labor conditions in Qatar for workers building the infrastructure of World Cup 2022 abound. Similarly, it is not difficult to find political and economic critics of Singapore. We shall not ignore these realities behind the splendours of the museums. Nor shall we forget how the museums of the past were built in France and England. For the British Museum see: Graham MacPhee, “British Colonial Archives Finally Released,” Counterpunch, 20-22 April 2012.. The dispute for the control and management of the cultural sphere shall not distract us from the fact that economic coloniality was behind the building of Western civilization museums as much as it is behind the building of museums of, say, Asian or Islamic civilizations.

At the same time, this should not confuse us into thinking that everything is driven by capitalism (economic capitalism), nor that the dispute for the control of the cultural sphere is irrelevant. De-Westernization (state-supported projects disputing the control of economy, politics, and culture) matters even if coloniality is still in place. Yet, the power of single stories hides from view the darker sides to such stories. On the one hand, museums are becoming multipolar in that they are paralleling the multi-polar economic and political global order. Meanwhile, non-Western civilizations are building their own museums and telling their own stories, thus delinking from their captivity in the contexts and collections of the British Museum and The Louvre. On the other hand, while museums in the past have been built on the shoulders of European imperial expansion, today, museums like the Asian Civilizations Museum and the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha are being built on the shoulders of the de-Westernizing political sovereignty of capital.

This text was originally published in Ibraaz in November of 2013