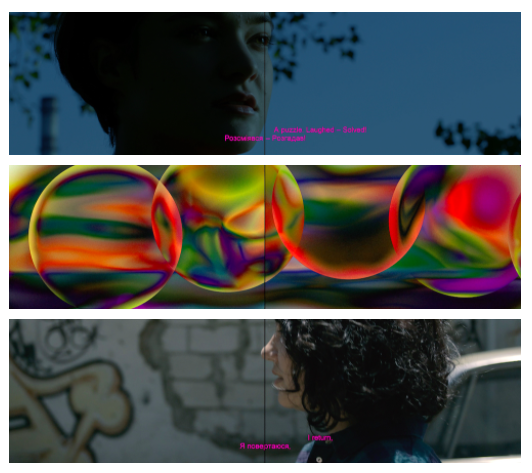

One of the main events at the upcoming Cosmoscow International contemporary art fair will be the “Turbulence” exhibition, organized by the Cultural Creative Agency in cooperation with the embassy of the State of Qatar. The exhibition will present projects chosen through an independent open call that reflect the new reality of our world as it faces the pandemic crisis.

Among these projects will be a self-organized gallery created by Ekaterina Muromtseva, who initially began the project on the balcony of her apartment in Zagreb while she was isolated there during the lockdown. This gallery will be replicated for the “Turbulence” exhibition in the center of Moscow and will exhibit Ekaterina's own works as well as those by other artists—Yevgeniya Yeremina, Varvara Grankova, Margo Ovcharenko, and Alexander Anufriev. We asked the participants of the upcoming show to talk about their projects and the unifying theme of the portrait genre.

EkATERINA MUROMTSEVA

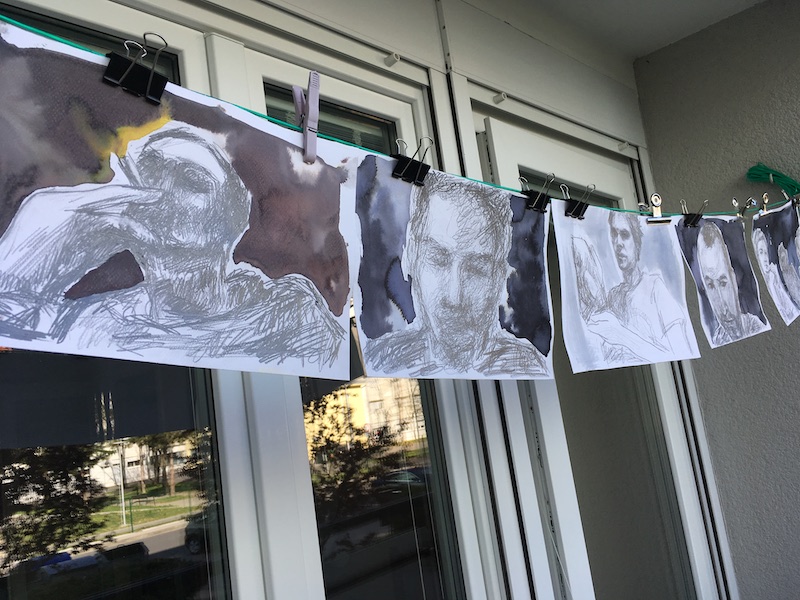

In November I found myself in Zagreb: I went there for an international artist-in-residence program created by What, How & for Whom curatorial collective members. Due to the virus, the program ended much earlier than originally planned, but one was still not allowed to leave Croatia. So, I was stuck in a rented apartment for nine months: being there was sometimes not easy because of the loneliness and the absolute uncertainty about the future, but drawing helped me. Once I had a phone talk with an Italian friend, who had already been in quarantine in Turin for pretty long, and he told me about Italian kids hanging their drawings out of windows to somehow cheer people up. This idea inspired me a lot and I thought of trying to do something similar. My flat with a balcony was the only public place I had to make exhibitions.

I started with my watercolors—the portraits of the shadows of cultural workers, whose job often remains invisible. I invited them to come to my place to be interviewed and painted at the same time. I enjoyed producing works where the visuality and the formal solution were closely connected with communication and everyday life, all of those perceived as one process. Plus, it was also a topic that I believed to be significant. In general, I can say that basically all the talks with artists and cultural workers in one way or another had to do with a discussion of ethical issues—because the employment in this area is often not regulated in any way and remains in a gray zone.

Later, I held other exhibitions at the balcony, mainly aimed at establishing communication with the outside world. With the help of portraits of dogs that were walked in my neighborhood, I was in touch with the neighbors; I also made exhibitions for birds who were frequent guests of my gallery. Then I started inviting other artists to be able to interact with them, albeit not in person. In general, this gallery initially did not have any concept or any specific rules—I have always appreciated its spontaneity and unpredictability. I came up with this idea as a response to a particular moment and now the gallery keeps evolving following the same impetus.

The balcony gallery opening and the beginning of the quarantine. Zagreb, 2020 Ekaterina Muromtseva. Exhibition for the Birds. Zagreb, 2020 Ekaterina Muromtseva. The Fly That Got in the Way of Great Philosophers Thinking. Zagreb, 2020 Ekaterina Muromtseva. Portraits After Skype. Zagreb, 2020

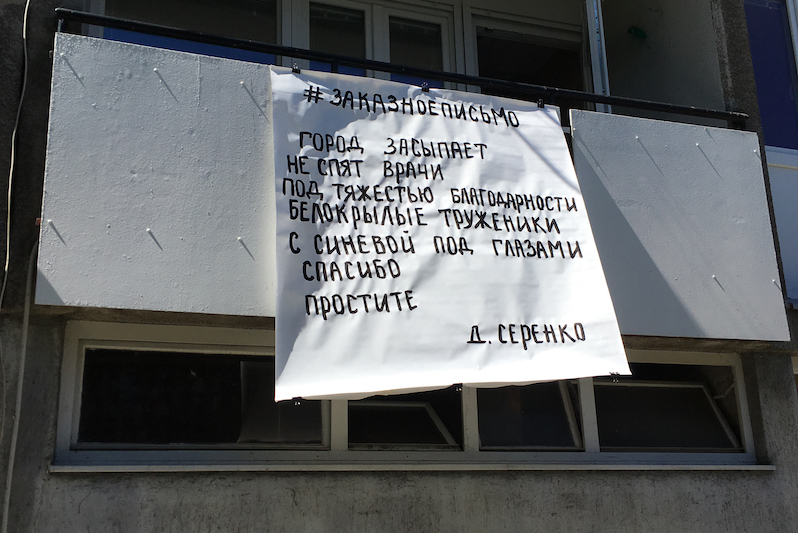

Ekaterina Muromtseva. Dogs that Walk Their Owners. Zagreb, 2020 Ekaterina Muromtseva. Bugs. Zagreb, 2020 Ekaterina Muromtseva. Quarantine Outfit, Part 2. Zagreb, 2020 Daria Serenko. Registered Letter. Zagreb, 2020

Jolanta Nowaczyk. New Normal. Zagreb, 2020

Although I wanted to turn my self-organized balcony gallery into a nomadic microinstitution, I never thought it would win in the “Turbulence” competition and be shown at Gostiny Dvor. I saw it as a good opportunity to interact with the local community and exhibit the works of various artists in the center of Moscow, such as Margo Ovcharenko and Alexander Anufriev, Varvara Grankova, and granny Zhenya (Yevgeniya Yeremina) who are also my friends. As for me, my participation there will consist of a continuation of my series about cultural workers—I think it would be especially interesting and important to do it in the context of a contemporary art fair. A large number of people will be employed there— invisible but still present—those who stand next to the booths, write texts, and so on. I see revealing this paradoxical situation as my goal. In general, everything that we are preparing for this exhibition is somehow connected with the portrait. And I really like this personified art form. Through the personal, one can reflect the time we live in, through the experience—reach the collective where we all exist side by side.

Right: Artist at the Garage Museum workshop. 2019

Since granny Zhenya is sick now and cannot give comments, I will tell you a little about her. For many years, I have been visiting nursing homes in different regions of Russia, where we use art as a way to get in touch with the elderly. I met granny Zhenya seven or eight years ago in the village of Tovarkovo, Tula region. Then she was only starting to paint, but gradually she got familiarized with the studio. She explained that she needed some kind of reference point and meaning in life and art began to play this role for her. Granny Zhenya can be called a naive artist, since she learned everything herself. All her paintings are made with strong emotions. I am amazed at her diligence: she sometimes draws for ten hours with no breaks. We made her a profile on Instagram when she was coming to Moscow for the “Bureau des Transmissions” exhibition. There one can check her works and follow her. Due to the illness, now she will not be able to make something new for “Turbulence”, so we are planning to show several female portraits that she created in 2019.

VARVARA GRANKOVА

Katya and I participated in the laboratory of “Praktika” Theater last year, I sang in a performance there. She really liked it and invited me to come up with something vocals-related for “Turbulence.” I was very much interested in this proposal, since I have been singing for many years, but I hardly use my voice as a part of my creative works and rarely perform. I am now working on a performance called “Shelter”: first I am going to lower a long plait of flowers and oakum from the balcony, like Rapunzel, and then weave myself into it like in a cocoon, at the same time using a loop station to double-track the sounds of my voice. I developed the idea specifically for this gallery, as I always try to do something new related to the environment and space where the work is going to be shown.

This project seems to be my first non-social project in a long time. After my personal exhibition “Nonviolence”, where I examined various aspects of violence in the context of both an individual and a whole state, as well as several projects dedicated to ecology and feminism, I feel tired of the social. In hard times of the global pandemic and isolation, I want to talk about the relationship between person and nature, the voluntary escapism and the desire to break free that inevitably comes from that. In general, this performance will reflect a lot of what I went through during the quarantine. For the first time in my life, I found myself staying in the village for a very long period and this taught me a lot—for example, I learnt to see the sky and observe the changes of the seasons. In Moscow I usually have no time for contemplation.

We have been friends with Katya for a long time, because we studied together. And somehow we have always been supporting and helping each other with various technical and theoretical issues. When Katya was in quarantine in Zagreb, she opened a gallery at her balcony, so as not to go crazy because of this isolation and boredom. I began to organize exhibitions there, including my own ones, where my photographs of doctors made in 2016 were shown. Now, after the victory at “Turbulence,” the gallery is going to be reconstructed at Gostiny Dvor, so we have decided to go on with this work—to take new photos related to quarantine and coronavirus. We are going to do it with Margo Ovcharenko: I will take pictures of doctors and Margo will present her photographs of hotel maids who hosted physicians during the self-isolation regime. It is important for us to show that these people are not some faceless functionaries and heroes, but ordinary Moscow citizens who are also at risk of contracting and suffering from the virus. And the portrait is the best way to show their humanness and the reality of their everyday lives.

Both Katya and I studied at the Rodchenko Art School, we met through mutual acquaintances who are also in photography. I was following her project in Zagreb, and in general I enjoy everything Katya does. Her statements sound very natural and in no way artificial or forced, her thoughts are relevant but do not necessarily reflect the current social situation. I would have been pleased to take part in her exhibitions even at that stage, but now that she has invited me to take part in “Turbulence,” I am also happy with it.

Together with Alexander Anufriev, for the upcoming exhibition we came up with a project about doctors and those who helped them deal with their household issues during the regime of self-isolation. In May, in Moscow I also took photos of city workers quite often—people for whom the coronavirus was a danger that they faced daily. I mean, not only doctors, but also, for example, taxi drivers and hotel employees. Several photographs of the maids of one of the Moscow hotels that hosted doctors who were fighting the epidemic are going to be shown at “Turbulence.” On the one hand, my interest is in taking a closer look at these twice invisible women doing low-skilled jobs and belonging to ethnic minorities that live in Russia. On the other hand, the idea is about shifting the focus of the discourse that now exists around doctors and other city defenders from heroic to humane by means of our artistic gesture. The point is to show them not as some abstract parts of a mechanism, but as people with their own fears.

The decision to make the portrait the main subject of the exhibitions was a collective one, since all of us—Katya, Sasha, and I—are not interested in a fictional character but in particular people. Actually, portrait is what I am mainly engage in—I try to break through the shell that people create in order to hide in, and to capture something intimate.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich