Kohl, or al-kuhl in Arabic, is a black powder used as eye make-up in many Middle Eastern countries. This bottle contains kohl mixed with water from the Zamzam spring in the Holy Mosque in Mecca. According to the Islamic tradition, the spring was discovered by Hagar, the mother of Abraham’s son Ismail. From their Pilgrimage to Mecca, Muslims from all over the world bring Zamzam water, or products containing it, as a spiritual souvenir. I bought this bottle of kohl in the bazaar in Jiddah for a friend interested in cosmetics but she left Berlin before I had the chance to give it to her.

Stefan Maneval

This article by Alina Kokoschka was originally published in the book Muslim Matter, which underscores the complexity and heterogeneity of Muslim lifeworlds. It includes material gathered at the Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies: photographs that researchers have recorded during fieldwork, objects and artifacts that they have brought back from the field, and accompanying essays that feature multi-disciplinary perspectives on the overlooked and sometimes under-represented aspects of everyday life across various Muslim communities and societies.

Islam is Muslim daily life. It is lived religion between mosque, school, kitchen, sports club, shopping, and fieldwork. This all defines what everyday Islam is and Muslims much more than the extreme positions that make headlines to help garner media attention. How can complexity and ambiguity be appreciated despite this tendency towards simplification? Turning to the tangible can help to grasp Islam and Muslim cultures and societies in an alternate, more comprehensive way. The situations and things of Muslim daily life that are depicted in this book provide insights into a life that is largely colourful, often playful, and not infrequently of fashionable interest. That these things become visible is thanks to the (in)sight of researchers, most of whom have spent years familiarising themselves with the affiliated regions and peoples. But it is also due to the book's chosen focus on objects. This text is about things—about what we can experience from and with them.

Why things matter

Whether purchased, self-made, re-used, refashioned, reconfigured, repurposed, sanctified or discarded: Things––their materials and forms of design, the employed images and symbols––make it possible to identify differences in Muslim life realities, and to appreciate the plurality of their local forms of expression. In addition to the important yet rarely discussed intelligibility of things, four other factors call for a new way of thinking––for a shift away from the text on its own, and a move towatds material culture: Things with a connection to Islam have multiplied exponentially in recent years. Things can be experienced, they enable and shape experiences––as much for external observers as for users. Things and materials play a particular role in the source texts of Islam. Lastly, one might note a qualitative and not just a quantitative change: Things with an Islamic connotation decorte and illustrate images and photos with increasing frequency.

From Ahmedabad to Yogyakarta, the sheer amount and recurrence of things with a connection to Islam have grown significantly in the last two decades, and many of these items command our attention: plastic that shines like gold, intensely bright colours, shimmering mother-of-pearl leather. The ubiquity of this type of aesthetics––its design and sensuality––has made it nearly impossible to avoid, which means that it merits focused attention. Muslim consumer culture, and the aestethics of the commodities that emerge within it, are global phenomena––not only as parts of export and transports, globally operating businesses, or the discovery of the “Muslim” target group.

On every continent, and in countries with varied underlying religious, political, social and economic conditions, there has been a growing tendency to consume as a part of lived Islam. The role of these commodities in contemporary Islam, for Muslim praxis, and in taking about Islam will be addressed below. Before discussing these topics, however, let us first consider what things can tell us.

From hats to shoes, from bleeding device to bar of soap: Things are concrete and present. This is notable given that in some of the countries represented here maintaining secrecy is a top priority—with regards to meddlers or busybodies for the general population; and for the state in terms of statistics, election results, or repressive practices. There is thus much that “cannot be known", and questions about facts and numbers are virtually irrelevant. Things and materials, on the other hand, inform in an unfiltered way about their surroundings and the engagements with them. They frame eras, regimes, social classes, stages of life and spaces, the borders of which are marked by production conditions and import-export pathways. In this sense, until recently, the socialist element of the Syrian Ba'ath Party had been reflected in the accumulation of goods from China. As enamelled dishes (made in the Peoples' Republic of China) were replaced by plastic and polyester ones (made in China, indeed the China of transformation), their metallic sounds have also turned synthetic; imported juice presses made of plastic exist in contrast to local and handmade tools of wood that are so compact that they are hardly breakable. And even if Syrian craftsmen are able to repair what elsewhere is seen as irreparable, the reality of a material such as plastic is that it cannot be permanently re-assembled once it is broken. Fissures in material and their ways of (not) being fixed might even be able to say something about political positions: While adhesive tape is at times used to sustain life, it is elsewhere omitted: a ripped seating surface should remain usable, the obligatory portrait of Bashar al-Asad next to it can be left to decay.

This salt-box, made of plastic and inscribed with the words “Ya Hussayn” (“Oh Hussayn”), is a daily ritual object present in every Bohra household. Before commencing each meal, Bohra Muslims take a pinch of salt symbolizing the tears of Imam Hussayn, a key religious figure who was martyred in the Battle of Karbala in 680 CE in present day Iraq. I acquired this object in the Alawi Bohra quarter in Baroda, India, due to its importance in the daily life of my fieldwork.

Olly Akkerman

Does it make sense?

It takes a good grip to be able to grasp things: Does the material of Islamic garb leave one sweating or does it cool one off? Does it caress the skin or is it coarse? What does the world sound like with a headscarf over the ears? Is it a soft click that Is made by the wooden prayer beads when they slide over one's finger? Even these best-known Islamic things remain unfamiliar when they are understood as belonging to the realm of the foreign and incomprehensible—that which is untouched or untouchable who has touched, tried or even themselves worn these things? Things enable human actions: indeed, they produce actions in that they shape processes and perception, and thus also bodily movements and gestures. That is how they directly impact consciousness and recognition. As the interface between world and body, things teach and make comprehensible; they are both expression and a means of expressing. They are the needed, desired, denied, that which decorates, protects, cares for, forms, benefits and determines, touches and is touching.

Sensory perception importantly influences how the world is experienced and shapes “self-awareness”—for observers, owners or vendors. Sensory qualities do not only shape one’s understanding of pleasant and unpleasant, or attractive and unattractive; they relate to values and ideals, to preferences, histories and aspirations, and to social, economic, political or ecological conditions. And this is how the aesthetic is highly political in its impact on the constitution of people, whether individual or community. As candid as the thing also speaks about itself and its histories through the traces of the past, as well as through the traces of the way it's used and of its design and material; as gracefully as it addresses all of the senses, requiring and promoting them, it is not always precise in its mode of expression: it presents itself differently to observers who have been socialised in the secular consumer culture of Europe or North America as to consuming Muslims in a society that only recently opened itself to the global economy. And also differently to Islam-critical or Islamic governments, and it offers a different meaning to theologians as to marketing specialists. Its use and value, what it can or is not permitted to be, is in the eye of the beholder, or, more precisely, the user.

Moreover, some view contemporary Islamic consumer goods as too profane, others as too kitsch, and still others as not sufficiently authentic due to their mass production. After all, they are measured against the grandeur of historical, illuminated manuscripts or inlays as insignias of high Islamic craftsmanship This openness of things makes scientific treatment of them ambivalent. How can one do justice to tins polyvalence in the museum, in science, or in the writing of reports?

The thing in Islam

Typically included as part of the material culture of Muslim societies are mosques and their furnishings, book arts, faiences and rugs—in other words, those things that are collected and displayed as “Islamic art”. Only some of the things shown here would be seen in a typical museum. Instead, among the exhibited pieces, the viewer finds mass-produced items as are available at a department store, and individual pieces that would best be found in a shop for ethno-accessories. Is a fan scarf or classic mens shirt as “merchandise” for the follower of a religious leader astonishing? Bright, pink-coloured objects for prayer or mourning might also surprise an observer: Islam as new fashion trend? Fashionable Islam?

The last two decades have included many additions to ritual and traditional objects—also among those selected here for display: Goods that were “made for Muslims” and “made by Muslims,” which, at times, help to support religious practices or, at other times, express the owner’s religious or religio-political orientation or knowledge about Islam in a contemporary way. Magical and cautionary things that protect or invoke pious living, such as charms and wall hangings, make up most of the commodities at a bazaar, department store, or online shop. Magical practices, also a means for healing with the written word, by no means constitute peripheral or rural phenomena. They are widespread, accepted and everything but new.

Headache bowl from Islamabad, Pakistan

This bowl is inscribed with Surah Yasin, a chapter in the Koran, which is said to have healing power. If you have a headache, drinking water from this bowl is supposed to relieve the pain. I got this bowl from a friend from Pakistan, and another friend of mine from Sudan now frequently uses it. At the Swahili coast, where I come from, Islamic healers write the Koranic verses with saffron ink into a bowl. The ink dissolves in the water which the patient drinks.

Jasmin Mahazi

Grave sheet from Ahmedabad, India

Textiles like this grave sheet are among the most common votive offerings that visitors make to saints’ shrines across South Asia. This particular multi-colored and glittery fabric depicts a prominent Sufi shrine of India along with verses from the Koran. While buying this object in the bazaar of Ahmedabad, the vendor urged me to enlighten the world beyond India about Islam as a religion and civilization.

Olly Akkerman

Fakir bag from Sehwan Sharif, Pakistan

Fakir costumes and textiles are mostly a patchwork of old and discarded fabric, emphasising not only the wilful poverty of such figures but also the distinctiveness of their appearances. Such textile-items include blankets, long and loose shirts, caps, and also shoulder bags. This fakir bag was purchased from a shop in Sehwan Sharif that caters to travelling fakirs from all over the country.

Omar Kasmani

Miniature flagellation knife from Ahmedabad, India

This miniature flagellation knife was acquired in the city of Ahmedabad, India, at the holy graveyard of the Dawoodi Bohras, a small but thriving Shi’i Muslim community. The knife is used during the annual commemoration of the martyrdom of Imam Hussayn, observed by Shi’i Muslims all over the world. It is commonly attached to a thread or a cord, which is then used to lash one’s back during mourning rituals. I bought it because of its odd miniature size since flagellation knives usually come in the size of a regular knife.

Olly Akkerman

Sheikh Yassin shirt from Sanaa, Yemen

Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, co-founder and spiritual leader of the Hamas movement in Palestine, was assassinated by the Israeli army in 2004. Studying Arabic in Sanaa at the time, I witnessed a public outpouring of Arab nationalism over the circumstances of his death: The old man in his wheelchair was hit by missiles fired from a helicopter as he was leaving a mosque after early morning prayer. When I returned to Yemen one and a half years later, the shirts of the Shaheed (martyr) fashion brand memorializing Sheikh Yassin in size XL were still sold in the streets of Sanaa.

Stefan Maneval

Fan article from Yogyakarta, Indonesia

I bought this item in Yogyakarta, Java, Indonesia during a celebration of the prophet Muhammad's birthday (mawlid) with one of the most famous Habibs of Indonesia (descendants of the Prophet). People wore it around their head and neck to show that they were supporters of this particular Islamic scholar known for his beautiful religious songs and sholawat, praises to the Prophet Muhammad. I find it interesting that a popular fan culture has developed around an Indonesian Islamic scholar similar to a soccer player in other parts of the world.

Claudia Seise

Muslim children's books from China

These children's books, purchased in Northwest China, cover Islamic history and ritual practices, as well as help children to learn Arabic. The titles of the books are: Stories of Prophets in the Koran, Learning the Ablutions, Muslim Blessings, and The Arabic Alphabet.

Markus Fiebig

Islam is understood by many Muslims to be all-encompassing and a holistic guide to life—similar to other worldviews that include comprehensive philosophical, theological, spiritual or socio-political positions about wide-ranging areas of life. Holistic means that all areas of life are relevant to the "proper” way of life. Depending on its interpretation, this worldview can “materialise” differently—in toys, toiletries, style, or medical equipment. A particularity of Islam within holistic ways of life is that things and materials play an important role in its sources, which Is to say in the Koran and Sunna (the passed-on sayings and actions of the Prophet Muhammad).

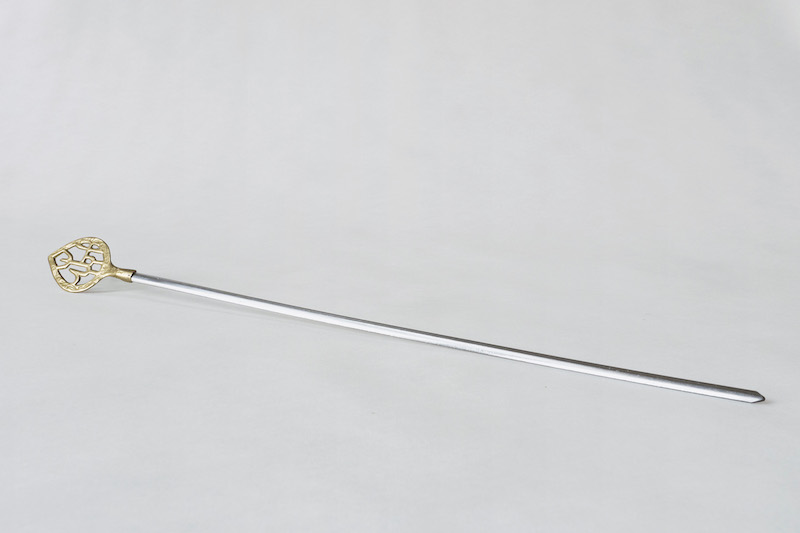

For example, concrete materials are mentioned, such as textiles or metals whose use would not be appropriate to this world, as well as those that mark the hereafter, or paradise. The extensive literature about the life teachings of the Prophet Muhammad mentions other things—optional or mandatory depending on one's belief—that can help to construct a pious life. Similarly, whether or not interpretations and modifications of those named things and materials are permissible is determined based on one's understanding of the source texts and the canon of religious literature thought to be accurate. Women's pink prayer shoes are thus a new variant on the typically black or brown’unisex" shoes for prayer. It is a materialised interpretation of this tradition that under certain circumstances, such as in winter, the feet do not have to be cleansed before prayer. Cleansing the shoes is sufficient. The bowl used to cure headaches is based on a widely shared belief that divine blessing (baraka) resides in the holy word (holy because Koranic and thus divine). Baraka has the unique ability to transfer into material, such as into poured water. The form of the bowl is dated and widespread in many regions; the production technology—industrially manufactured stainless steel, engraved by hand —is more recent. The skewer with Allah logo is particularly remarkable. Meat is subject to stringent regulations according to all schools of Islamic law. The animal must be slaughtered and pork is taboo. Nonetheless, the religious marking of a tool for the preparation of meat is rare and introduces questions, such as whether the healing power of the holy name could function here too.

In a small corner of the Konya bazaar, hidden behind stacks of shoe boxes from the last five decades, I discovered these sock-like shoes or shoe-like socks. In the midst of all the brown and black models, I was drawn to their iridescent surface and unusual color. Especially when it is cold, the prayer shoes simplify the ritual washing before prayer, because you don't need to take them off, just wipe them off. The shoemaker of this model had the idea of designing a very appealing model for women—handmade, just as his father had done before him.

Right. Skewer for köfte (meat loaves) from Istanbul, Turkey

Grilled meat loaves are essential in Turkish cooking. I discovered this skewer in the whole-sale section of the Istanbul bazaar and found it interesting because it does not have the usual floral design: the calligraphic handle reads “Allah” instead.

Alina Kokoschka

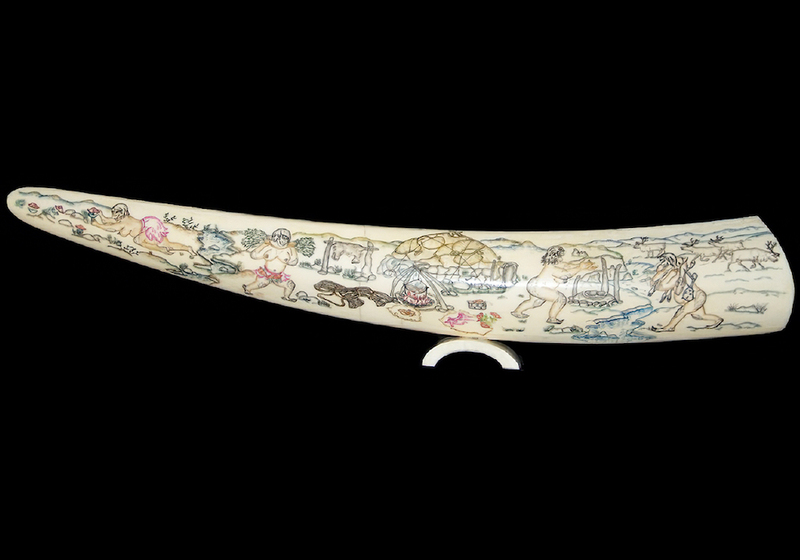

As these examples demonstrate, the borders to decorative and adorning objects are fluid. "Embellishment" offers great potential for new or seemingly new things in Islam. Connections with global trends are unmistakable at the toy market: Illustrative images play an increasingly important role, especially in the style of comics, which are already familiar to children for other reasons. The binary division of the sexes through colours with corresponding character traits is a phenomenon that extends beyond national and cultural borders. Ali's sword might also be considered an Islamic variant of the widely seen gun as the typical toy for boys.

What is happily sold in one country can be a source of irritation in others. It is nearly impossible to fully account for the diversity of uses and ascriptions of meaning in the world's varied Muslim cultures and societies, especially as Muslim consumer and popular culture have been insufficiently researched. Scientific exchange about material phenomena that extends beyond the national and temporal boundaries of nation-states, epochs and dynasties is needed as is the understanding that one analysis is rarely absolute. A comprehensive picture is often only possible with the combined perspectives of multiple scientific disciplines and regional expertise.

The Zulfiqar, literally “the one with a spine,” is said to be one of the swords of Muhammad, which was then borne by his cousin Ali in a crucial battle. With this it has become a key symbol of Shiite Islam. Today it serves as one of the most prominent symbols in product design for a Muslim target group. A plastic replica for children was a surprise to me since the zulfiqars on sale usually are decorative items. This toy adds a religious note to the wide selection of combat toys for Syrian boys.

Alina Kokoschka

A matter of context

What is certain is that a thing does not only speak for itself, that it has meaning and impact through its use and environment: the context of goods that are displayed left and right in a shop window, and of the things that are in a display case or in cardboard boxes, waiting for better times or for their disposal, but also the context of a society, its represented confessions, and the global flows of goods. If a DVD of "The Adventures of Tintin'' is on the shelf of an Islamic bookstore in Beirut, the drunken boorishness of the captain is not in the foreground. Much more decisive in the teaching of children about a moral way of life—which is its own genre in Islamic toyshops with sections like environmental protection and day-to-day courtesy—are demonstrations of courage and loyalty, or standing up for a just cause. When, as is so often the case, the two-sided sword that Prophet Muhammad gave to his cousin Ali hangs on a keychain next to the playboy bunny, it might emphasize the sword's symbolic masculinity.

The expansion of the contemporary world of Islamic things and goods is part of a general trend in which the cartography of consumption becomes more complex and differentiated. The commodities that are designed for Muslims and that take shape under these conditions mainly target “the Muslim”, not least because producers strive towards an international market and manufacture for the masses. However, local and religious differences internal to Islam are often decisive in determining whether or not something is perceived as attractive, chic, worthwhile, or pious. They are this actually for the target group “Muslims”, which is apparent in the cut and pattern of clothes, in how people are depicted, or in refraining from granting importance to ornaments or to colour and material selection.

What does it mean for the onlooker and observer of these trends? It means that only a deepened knowledge about the development of visual and material culture makes classification possible if it is possible at all. And that sometimes first-hand experience helps: to experience an Islamic garment in Iran with its “folds” of resistance that dwell in the detail of the model and its cut, and the movements that they allow; in Syria, to experience the comfort of being protected from glances, but also the discomfort of black polyester in the summer; in Germany, to experience everyday exclusion and prejudices.

The kofia is a traditional head covering worn by Swahili men as an expression of their Islamic faith. My cousin Aisha knits kofias and sells them to make ends meet. She has made this kofia (the finished one) for my husband. He hides his dreads in it to show respect when he is attending a funeral or a wedding. Before I moved to Germany, Aisha taught me how to make one myself using a porcupine spine found in the forest to make the holes and a cowrie shell from the seashore to iron the hat. Aisha asks me if I have finished the kofia whenever I visit her in Lamu. But as you see I have just begun.

Jasmin Mahazi

A flood of images

A characteristic of contemporary Islam is the enhanced presence of explicit visuality as is seen in the children’s books and in the wal hangings with visual depictions of religious leaders. In these examples, their portraits are assembled into collages with photos of sacred sites. This technique of leaving visible the process of production with digital image manipulation is popular in Pakistan and India, in Syria, in Yemen or even in Germany. We also see it in images on walls and on signs of doner-kebab stands, and in living rooms and magazines in the Middle East. Despite the religious variants and differences that are visible just when one considers the depicted "saints”, reoccurring aesthetic forms are discernable. The loose visual arrangements next to and on top of one another are by no means an indication of unfamiliarity with the digital techniques of photo editing. Illustrated here is a fundamentally different understanding of image composition that is also recognisable in the rich tradition of Islamic miniatures.

With the montage visible, the impression of depth is inhibited. It is not reworked with vanishing points or shadows. Parts and patterns are often spread out and pasted onto bodies. Similarly, historical miniatures often depict a spatial environment yet refrain from portraying it in perspective. It does not help to improve understanding by simply emphasizing this absence of depth—and the figurative meaning of depth is also often implied—or describing the works as deficient of aesthetic sensibilities. Can space only function through the presentation of distance? Is this really about the representation of space or are other relations at play? The question is what becomes visible in the two-dimensional staggering of images. Rather than the different sizes of depicted persons referring to the distance of the viewer, without depth it is possible for size variation to depict hierarchies, for example, or for an arrangement to communicate connections and influences.

Visual representations are integral to Islamic history and are thus in no way novel. On the streets, on rear windows, in window displays and in living spaces, the frequency of images of the Kaaba, the Dome of the Rock, praying girls and rose-covered martyrs has visibly increased. The nature of these representations has changed as photographs and photo-like images lead the market. That which is referenced—for example, Mecca as the holiest site—is depicted with all of the pilgrims circling the Kaaba and without the encryption that one finds in graphic abstraction. The trend towards explicit, photographic or photo-realistic depictions is particularly insightful considering the existing emphasis on the implicit and abstract in “lslamic art”. Key religious moments, faith practices or spiritual insights are increasingly represented and conveyed in new ways. Calligraphy and ornaments in Islamic crafts and architecture are not mere abstractions used to avoid the pictorial. With graphic abstraction, one can also express and experience abstract spiritual insights that are difficult to depict with concrete images. Concrete images show something else; for example, they can more directly convey emotions from a pilgrimage to Mecca.

This pendant is from the holy graveyard of the Dawoodi Bohras in Ahmedabad, India. It is worn as a talisman and contains the picture of the late Da’i, or spiritual head, of the Dawoodi Bohra, a Shi’i community I studied for my fieldwork. Since his passing away in 2014 and the subsequent nomination of a new spiritual head, new talismans no longer carry the same picture making this pendant extra special..

Olly Akkerman

Right. All-saints poster from Sehwan Sharif, Pakistan

Pictorial representations of saints and Sufis are widely popular across Pakistan especially as souvenirs that devotees bring home after their visits and pilgrimages to Sufi shrines. This poster depicts an assembly of the most prominent saints of Pakistan along with lesser known figures, living saints, and more contemporary Sufi masters. The Urdu couplet at the bottom of the poster reads: “serve the fakirs, if you seek the heart’s longing; for this jewel is not to be found in the treasures of kings.”

Omar Kasmani

The significance of images for showing religiosity has increased, which has changed what it means to recognize and understand. Therefore, the patterns of perception and the possibilities of knowing have also changed. Indeed, these all take shape differently with images than with writing or symbols. It remains that Arabic writing also and above all includes a visual potential, and that one must learn to read images and writing equally. What remains uncertain are the effects of these aesthetic shifts in contemporary Islam, and of the remarkable growth of things in Muslim cultures and societies. These discussions have only just begun.

If we want to understand what constitutes Muslim life, what causes the seeming strange to seem strange—at a time when, for example, shoes in metallic paint are also on the must-have lists of magazines outside the Muslim world—we need an overview of existing aesthetic forms, means and practices. Overall, there is still need to identify the core features of design in Muslim contexts today, or to understand the uses and handling of materials other than just retrospectively and with the distance of a showcase. Appreciating and finding words for the visual and material languages of contemporary Muslim life is one way to understand the longings, fears, values and role models of the “other”—as much as of oneself.

Translated from the German by Todd Sekuler

All photos by Marina Thies

Muslim Matter

Revolver Publishing

Berlin 2016

ISBN 978-3-95763-359-0

18 x 24 cm, 192 pages

Languages: German/English

Editors: Omar Kasmani, Stefan Maneval