Right: Staircase after conservation. Frontal view from first level

Tbilisi, Georgia, May 2019. Photo by Gio Sumbadze

The conservation of traditional architecture is no easy feat; in addition to the physical task, there is a wide variety of bureaucratic, financial, material, and social hoops to jump through. Thomas Ibrahim and Francesca Crotti are two of the original members of the Kibe-Projekt, founded as part of an effort to repair an iconic wooden staircase in the Vera district of Tbilisi. They introduce the history and framework of the project, and through a series of short stories, reveal some of the unexpected twists and turns of preserving these spiral stairs.

The Kibe-Projekt was a conservation initiative focused on the futurity of the Ezo (ეზო, courtyard) House typology in Tbilisi, Georgia and the symbiosis between tangible and intangible heritage. The project was made to address the rapid loss of 19th cultural heritage in Tbilisi in response to the ongoing gentrification processes that are degrading the urban fabric of the city and undermining both the social dynamics and habits of this distinctive typology.

Tbilisi’s 19th century houses demonstrate an aesthetic assemblage of regional architectural features from periods of territorial expansion of empires bordering Georgia. The houses reflect Persian, Ottoman, and Arabic influences, coupled with European elements that were introduced in Georgia after its assimilation into the Russian Empire, at the end of the 18th century. The facades of the 19th century buildings are characteristically Art Nouveau, while the interior balconies and loggias are influenced by European carpentry. This aesthetic assemblage was further complexified with the subdivision of houses under the Soviet kommunalka laws in the 1920s, which resulted in the physical partitioning of the properties, and produced the communist social structure. Ezo Houses demonstrate nearly 150 years of morpho-political evolution in overlapping material layers. Simultaneously, they serve as an expression of the ongoing processes of appropriation and the changing building technologies and techniques adopted by the collective of residents in each house.

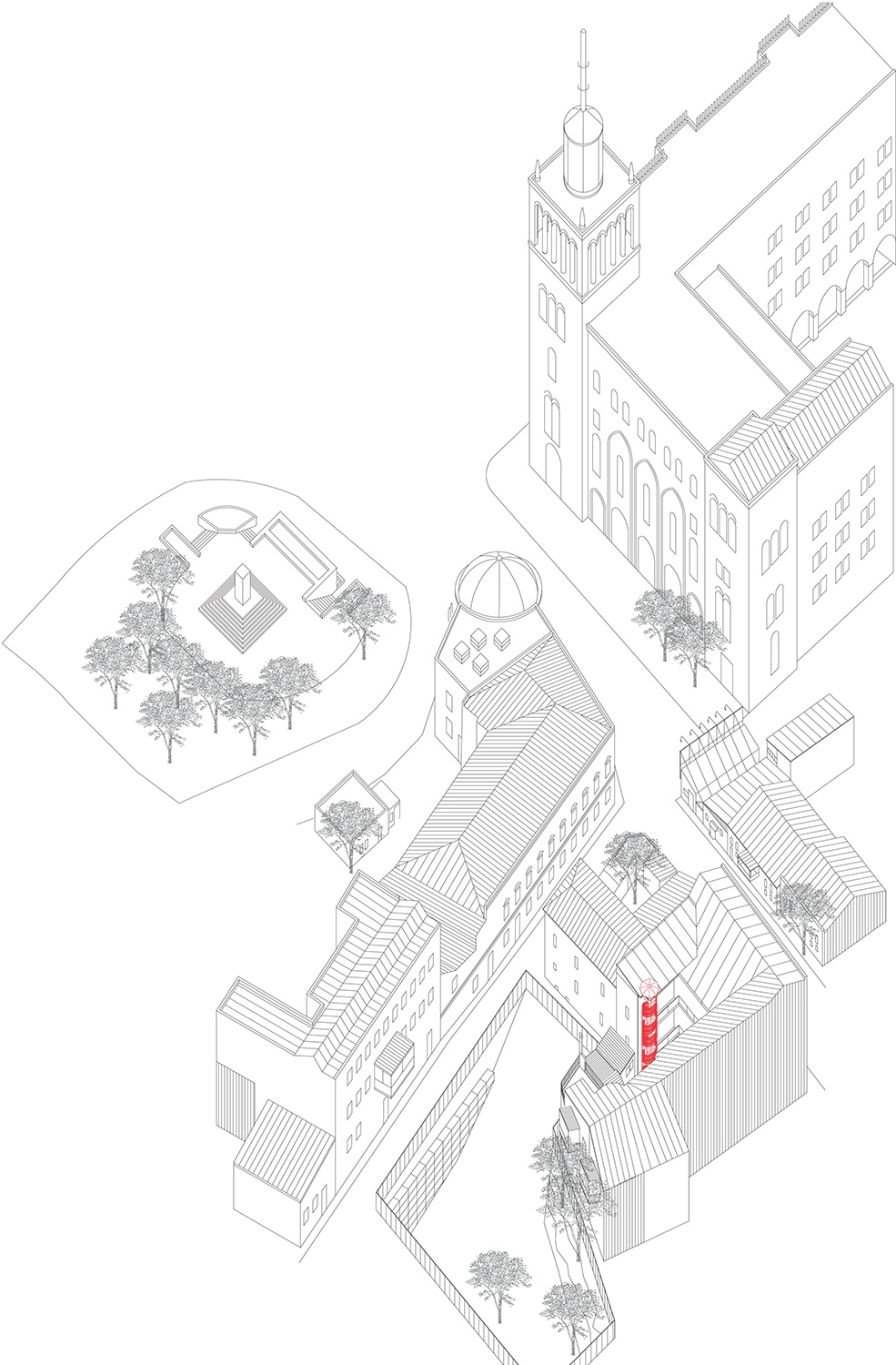

Right: Site Axonometric of staircase and 7 Dzmebi Kakabadzeebi House in urban context. Vera District of Tbilisi, 2018

Photo and digital drawing by Thomas Ibrahim

Our initiative was focused on the conservation of the kibe (კიბე, stairs) assemblage through a focal intervention, and with an emphasis on an embeddedness to the physical context, including the community. Since this strategy takes into account the residents of the house as agents who affect space, we were able to first produce a creative effect that energized both the house and community. This initiative arose from the need to oppose the post-Soviet trend of large-scale, government-subsidized conservation projects, as well as the private sector trends for rapid real estate development. These processes have led to the erasure of several historically significant buildings in Tbilisi; undermining local social dynamics unique to the city, and irreversibly altering the urban morphology.

STAIRCASE STORIES

1. How it All Started

Kibe-Projekt began with the solicitation of the conservation of the staircase to Thomas, who by chance was a resident in the particular courtyard that the staircase was located. Several neighbors brought the imminent need for the conservation to his attention, and the fact that there was little governmental support for small-scale conservation projects solicited by communities.

This is a typical condition for heritage conservation, where the resources allocated are limited, and the bureaucracy is dense.

2. Covid, Fundraising, and Assembling a Team

After a couple of years, a potential sponsor contacted Thomas while he was outside of Georgia, with the promise of finding financial support for the project. He then solicited international fellow colleagues to come to Georgia for the conservation initiative, and a team of Georgian architects and conservationists who were interested in saving the staircase.

The sponsor would eventually be ineffective with fundraising.

3. The Neighbors and the Notary

After months of setting up a platform for fundraising and working on surveys and applications, and the moment finally came to get serious about the project, the neighbors who initially asked for support in fixing the staircase, got cold feet. Some individuals decided to contact all of the would-be developers in town to see if they would buy the building and demolish it to build a skyscraper in its place and provide them all with new apartments. They now were considering that the conservation of the staircase would anchor the building for the foreseeable future, making it difficult to cash out.

In 2005, the same offer was made to their neighbors in an adjacent lot. They gave their property to real estate developers to receive apartments in a new building on the same site. That lot is currently a giant hole in the ground collecting rainwater, as well as an “improvised urban wildlife preserve.”

4. No Money, No Staircase

When the moment finally came that we had the building permits ready, after the successful completion of the municipal applications, there was 3,000 EUR in the kibe bank account, more than 10% of the project budget, but far less than was promised by the sponsor.

During the fundraising period, there was a media promise by the municipality to fund the project if 10% of the budget was raised. Neither promise was fulfilled, so the initiative team turned to the private sector for support.

Organization and preliminary analysis. October 2021

Photo by Gio Sumbadze

Router table built for clearing decayed wood in central column. March 2022

Photo by Thomas Ibrahim

Installation of first level. May 2022

Photo by Thomas Ibrahim

Handrail installation. July 2022

Photo by Thomas Ibrahim

Supra (feast) on project completion date. August 2022

Photo by Thomas Ibrahim

5. Kibe Begins

The project began in November 2021, and continued on through August 2022. The entire process was open-source, shared on the project’s website, with full documentation of the methodology and credits to participants. The project was executed pro bono with the assistance of nearly fifty volunteers, spanning across different fields of expertise from painting, sculpture, and photography. A large and diverse artistic community gathered together for the completion of the task.

As an alternative to the status quo of local conservation malpractice, we salvaged more than 50% of the original wood, making substitutions when absolutely necessary, and with materials consistent with the originals. Our team preserved the original structural and aesthetic qualities of the staircase, including the production of a natural paint with local pigments.

6. Get off my staircase!

After the project was completed, we would be greeted by some neighbors with great admiration, and many were inspired to treat other elements in the courtyard. Others saw the completion of the project as a prospect for new AirBNB ventures.

Occasionally, when we try to hold lectures in the courtyard, we are asked to get off the private property. Meanwhile, due to the war in Ukraine, real estate values have tripled, and some neighbors have taken the approach of advertising the courtyard as a vintage Tbilisi experience for international guests.

We hope they enjoy the view, and leave a nice review!

Left: Top view of balustrade and steps after conservation. August 2022

Photos by Andro Sulaberidze

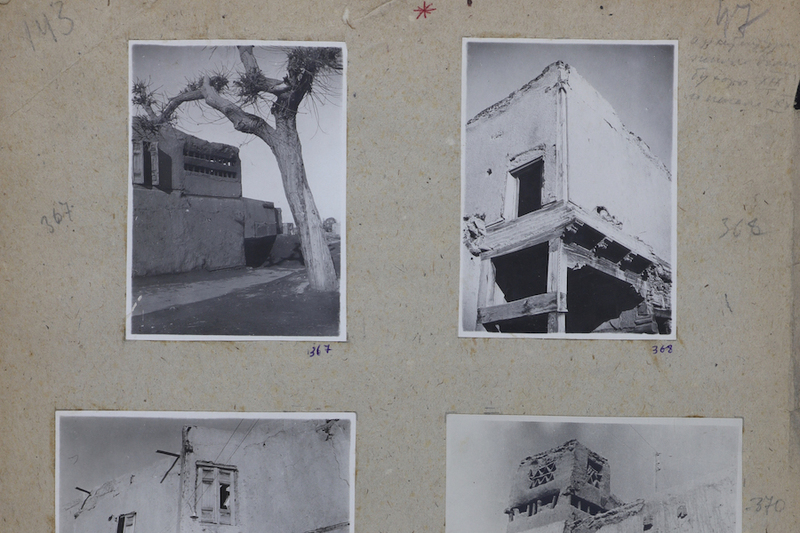

Right: Roof deconstruction. October 2021

Francesca Crotti