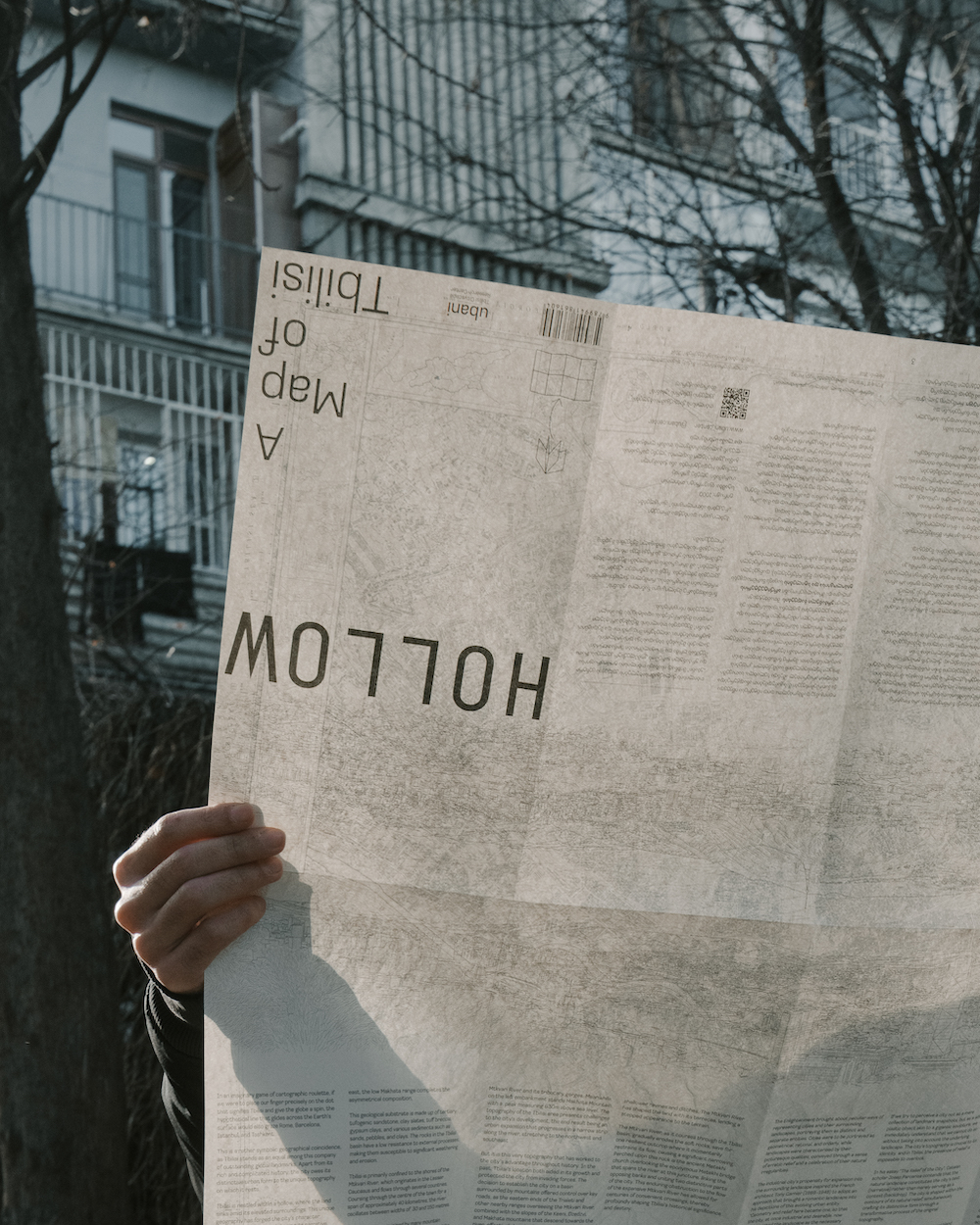

Ubani—Tbilisi Cityscape Research Centre was recently established in Tbilisi, Georgia by a collective of architects, art historians, and cultural managers. Its mission is to curate a comprehensive repository of knowledge dedicated to the cityscape of Tbilisi, delving into the intricate fabric of the city’s landscape, architecture, and urban development. The Ubani team has created and released a map of Tbilisi, portraying the city’s layout against a carefully rendered landscape. “Hollow: A Map of Tbilisi” merges two rarely combined cartographic codes: detailed topological phenomena and a concise schwarzplanschwarzplan A two-dimensional map of an urban space that shows the relationship between built and unbuilt space. Below is an exclusive online publication for EastEast: an essay from the authors at Ubani that accompanies their unique map of Tbilisi.

The Enlightenment brought about peculiar ways of representing cities and their surrounding landscapes, portraying them as distinct and separate entities. Cities were to be portrayed as geometrical, rational, and orderly, while landscapes were characterized by their picturesque qualities, conveyed through a sense of erratic relief and a celebration of their natural irregularities.

The industrial city's propensity for expansion into the surrounding landscape inspired the French architect Tony Garnier (1869–1948) to adopt an approach that brought a romantic landscape into his depictions of this evolving urban entity. “Geometry and relief here became one, so that the city, at once industrial and desirable, now incorporated the landscape as the necessary condition in the shape of its urban growth.” urban growth.” Parserisa Josep; “The Relief of the City”; Perspecta, Vol.25; 1989This marked a period when, perhaps for the first time, the significance of the landscape in urban planning was contemplated: “Garnier’s plan inverts traditional discourse. Order is no longer a condition foreign to the landform and relief becomes instrumental for composition.”

This map of Tbilisi Hollow offers a blend of two codes that are not so commonly encountered in combination: intricately depicted topological phenomena and a concise schwarzplan, the combination of which illustrates how the contours of urban form intertwine with the landscape.

If we try to perceive a city not as a mere collection of landmark snapshots, but as a whole plastic object akin to a gigantic sculpture, we immediately understand that we cannot do so without taking into account the underlying landscape. The city's topography is crucial to its identity, and in Tbilisi, the presence of relief is impossible to overlook.

In his essay "The Relief of the City", Catalan scholar Josep Parcerisa contends that the natural landscape constitutes the city’s text (narrative) rather than merely serving as a context (backdrop). The city is shaped within the contours of its natural relief, simultaneously crafting its distinctive form through a transformative process of the original topography.

Tbilisi's cityscape emerges as an alchemical blend of two key elements: its undulating relief and captivating storyline. While the interplay of relief and history shapes any city, Tbilisi stands unparalleled in this regard. The city's distinct topography and regional positioning have significantly influenced the intensity of historical events that have, in turn, defined its unique appearance.

The sculptural form of Tbilisi is threefold in its peculiarity. Firstly, the mountainous relief, etched with rivers and lakes, constitutes its character. The strategic significance of this settlement, situated in a perpetually tumultuous region, invited successive invaders who repeatedly demolished the town. It underwent multiple reconstructions, adapting to the building codes of the prevailing hegemony. Secondly, throughout history Tbilisi's city fabric has borne the imprints of various cultures—Greeks, Romans (both Western and Eastern), Persians, Arabs, Turks, Europeans, and Russians in their imperial and Soviet iterations. It stands as a captivating collage, a scattered catalogue of historical urban grids. Lastly, the city serves as a repository (albeit one that is not meticulously maintained) of diverse architectural typologies and styles, spanning from ancient churches to bold expressions of Brutalist masterpieces.

Zaal Andronikashvili, a researcher of the cultural history of Georgia, defines cosmopolis as a “place where particular becomes universal, a city that lacks any internal or eternal order. Rather, anybody, as a citizen or visitor, creates his or her order by the routes they draw in the citythe cityAndronikashvili Zaal, “Tbilisi Cosmopolis”; Archive of Transition; Niggli Verlag; Tbilisi. 2018.” Tbilisi aligns seamlessly with this description. Its scattered assembly of distinctive details and elements coalesce into a kaleidoscopic pattern that continually rearranges itself with each turn of the optical instrument.

Ubani — Tbilisi Cityscape Research Centre commits itself to investigating the complexities of Tbilisi's topography and urban structure in order to construct a comprehensive and multifaceted narrative. Utilizing diverse disciplines, approaches, and media, Ubani aims to preserve, adapt, interpret, and generate knowledge about the Tbilisi city form.

All images courtesy of Ubani, © Grigory Sokolinsky