This essay by Arjun Appadurai, a prominent anthropologist and a major theorist in globalization studies, is part of minor cosmopolitan: Thinking Art, Politics, and the Universe Together Otherwise—a book edited by multifaceted decolonial thinker Xiang Zairong and published by Diaphanes. This assemblage of texts and artworks has been the outcome of the “minor cosmopolitan weekend,” a three-day event curated by Xiang Zairong that took place at HKW Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin in December, 2018.

“minor cosmopolitan,” writes Xiang, “takes the ‘ism’ out of ‘cosmopolitanism,’ for ism, even in its pluralized version, seems to be premised on a false division between theory and practice (a trademark of eurocentrism), which in turn saturates a colonial north-south, east-west division for which we are paying a deadly price. [...] Importantly, the disproportionate power of a little suffix, like the tiny ism, teaches us that we need to use all small words, like ‘minor,’ with care and attention.”

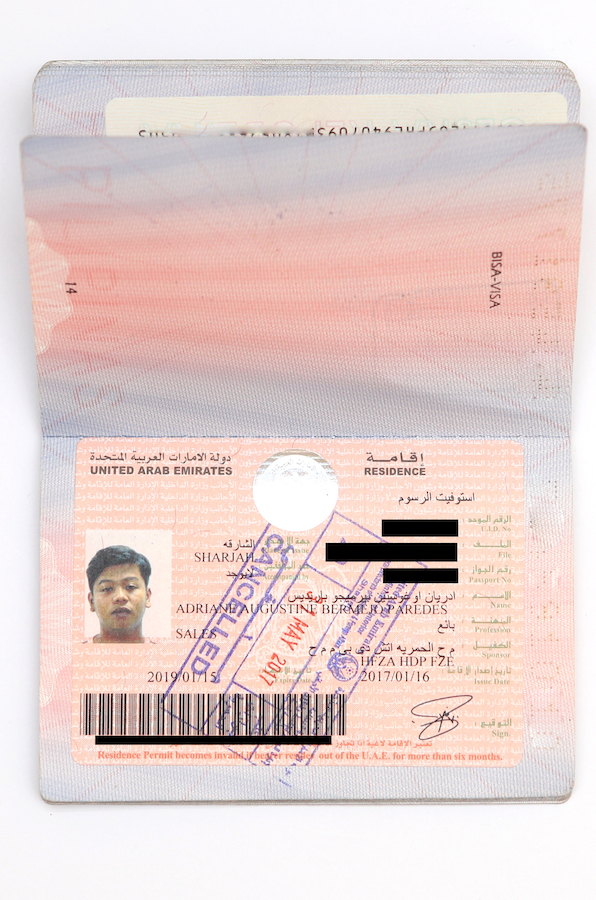

I focus here, briefly, on a small object with big capacities. Passports are not only small, they are also virtually identical in size due to the growing standardization of immigration rules, of scanning machines, and of visa needs across the world. Their small size disguises the fact that they are containers for something large, namely the nation-state of which the passport holder is a citizen. Thus, the small passport is a container and a condensation of the always bigger nation which issues it. Furthermore, the issuance of a passport makes even the smallest nation equal to the biggest and most powerful. This illusion of formal equality is the cornerstone of the international regime of the nation-state and the mutual recognition which is its most important precondition.

The small passport is a container and a condensation of the always bigger nation which issues it

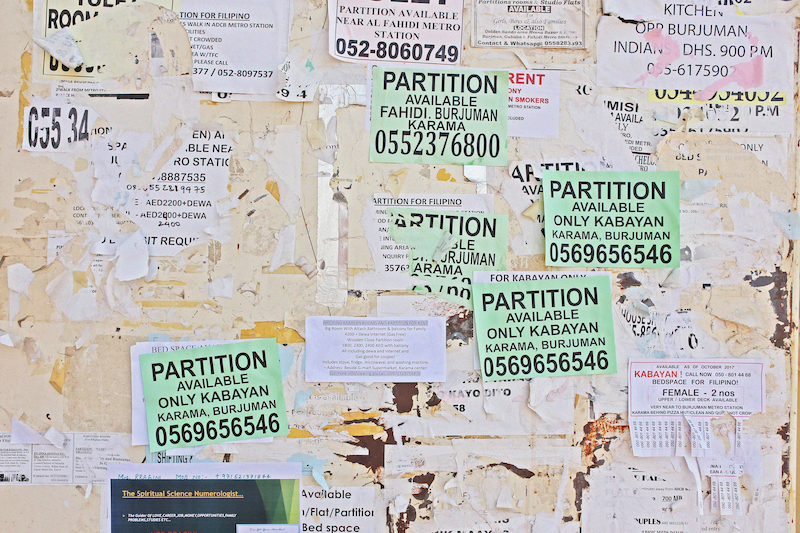

Passports signify citizenship but not all citizens have or need passports, because passports are typically used to travel (whether for students, tourists, refugees or job-seekers). But without the passport, citizens cannot usually exit their nations. So, the small passport is also something larger, a prison, or the nation seen as a prison. The passport is, in this respect, a tool of incarceration and immobilization, as it also is, for example, for guest workers in authoritarian states, such as Filipino, Indian, Pakistani and Indonesian domestic workers in the Gulf, whose employers confiscate their passports, thus turning them into slaves in the labor Market.

At the other end, the passport is a screen and a sieve, allowing some to enter and others not. In this case, the passport is tied to another small object, which is the visa, usually stamped or attached to the passport. This most powerful cousin of the passport is much harder to get for most people who want to travel from poorer places to richer ones. The visa is the secret master of the passport, although it appears to be a servant or supplement. Without the right visas, the passport means nothing. It is, in some ways, an empty object.

The passport is leaky from every point of view

The passport, from the point of view of both the nation which introduces it and the one which inspects it at the border, is also a leaky object, in spite of its smooth and closed exterior. It admits exceptions, abuses, fakes and frauds. It is always an object of suspicion. For the citizen in his own home country, the object of suspicion is both the document and the holder, both of which may be disguising some criminal intention or market. For the inspecting immigration officer, not only are the document and its owner objects of suspicion (because both one or the other could be fakes), but the issuing nation is also an object of suspicion, as a suspected home of drugs, arms, criminals or terrorists. Thus, the passport is leaky from every point of view, because it is the site or surface of that epistemology of suspicion which the system of nation-states seeks always to deny, but which is its primary weakness. Not all citizens deserve passports (in the paranoid view of the nation-state) and not all nation-states issue legitimate passports, according to those who inspect passports at borders. The passport is an effort to contain the nation and eliminate suspicion, but since the nation and its borders are always leaky, the passport is mostly an effective container of suspicion, but a leaky container of national citizenship.

So, what about the relationship of this small object to mobility? Well, the passport is as important a means of producing mobility as it is of producing immobility. In fact, visas are the tools of mobility whereas passports are mostly the tools of immobility, whether at or within the borders of the nation-state. There is one exception to this rule, and that is for rich individuals who wish to flee the tax regimes of their own countries and buy passports in countries which seek wealthy citizens for their economies and do not mind selling their passports in this market. The latest surprising member of this club is Singapore, which has promised a certain form of virtual citizenship to all those who invest in their new brand of national cryptocurrency. For these people, the purchased passport is the same as a visa for their new national domicile.

It is the currency of entry into a political form which runs against the inexorable logic of globalization

Like all objects, the legibility of the passport comes from its membership in a set. This set is a series of sacred national objects, which includes the flag, the postage stamp, coins and currency, the national anthem and national monuments. The passport is among the humbler of these objects, but it is special, insofar as it is unique for each citizen although it is given to many citizens. It is a site of national identification but not a site of national identity, and thus not sacred in quite the way the flag or the national anthem are sacred. It is leaky but it is strangely secular.

For refugees, migrants, and asylum-seekers in privileged states, like Germany, the struggle to get a passport is hard and arduous, and getting it is a big victory. Thus, this small object can mean a lot. The tragic sublime of the passport is that it is a precious object for many who seek to move to a better life, but, in fact, it materializes the leaky, suspicious, and obsolete idea of the nation-state, and thus it is the currency of entry into a political form which runs against the inexorable logic of globalization.

Long Night Stands with Lonely, Lonely Boys started as a photography project and has been simultaneously developed for over five years. What started as a documentation of encounters with different people in different places turned out to be a journey of seeking home overseas, filling voids, and understanding love and longing.

“As a Filipino migrant worker in the Gulf, my voice is as tiny as the speck of dust in the desert, yet my story is a million others’ stories. This project aims to help tell my story in ways that can shed light to other people’s stories, in the hopes that they may gain the strength to find their own voices,” writes Paredes.

This project will soon become available as a book.