“On the back of the walrus tusk, we see a different scene. A man and a woman arrive at the fly-agaric people’s camp by reindeer-drawn sled and engage in sexual contact with them. The journey itself is probably the result of mushroom consumption. The action is not directly depicted in the engraving, but the fact that it did actually take place is eloquently evidenced by the previous episode which depicted the gathering of fly-agarics in the tundra.” This is how Elena Batyanova and Mikhail Bronstein interpreted the images engraved on the tusk in their article “Fly Agaric Mushrooms in Daily Life, Beliefs, Rituals, and Art of the Peoples of the North.” The image was made by Lidia Teyutina, a Chukchi engraver from the village of Uelen, Honored Artist of the Russian Federation. As Batyanova and Bronstein write, in her youth she often heard stories about fly-agaric people, but did not dare to address this forbidden topic for more than forty years of work at the Uelen bone carving studio. And only in 2008, four years before her death, she finally decided to depict what the elderly people used to speak about on an engraved tusk.

Magadan Regional Museum of Local Lore

The researchers do not report on what exactly the old people told her, but fly-agaric people, or rather fly-agaric girls, can be found in one tale of the indigenous Kamchatka inhabitants—the Itelmens. Its protagonist (who is more of an antihero) Chelkutkh finds beautiful fly-agaric girls in the forest and stays with them, forgetting his wife Sinaneut and his son. Moreover, when the son is sent to his father to remind him of his home, he orders the fly-agaric people to drive the child away twice. And only hunger, skillfully organized by Sinaneut, makes Chelkutkh remember his family and ask the girls to bring him back. The wife greets her lost husband saying the following, “Why are you living with these fly-agaric girls? Why aren't you living with your own fly-agarics? Why have you returned here? You are doing very well! You have driven your son up the wall, so now get what you deserve!” But in the finale, having taught him a lesson, she still lets him in, while the “fly-agaric girls” dry up and die. In another fairy tale, Sinaneut finds a wife for her brother Ememkut among fly-agaric girls. In the third story , fly-agaric girls get caught in the rain and climb into the ear of Ilek—another protagonist of fairy tales—to make a fire there and dry out.

Fly-agarics played a really significant role in the life of the Chukchi, the Itelmens, and the Koryaks of the Kamchatka Peninsula. When writing about the use of fly-agarics as an intoxicating and hallucinogenic agent, Batyanova and Bronstein refer to the descriptions given by the participants of the Great Northern Expedition of the mid-18th century Stepan Krasheninnikov, Georg Steller, and Jacob Lindenau, as well as to the books and articles by the ethnographer and writer Vladimir Bogoraz, who studied the life of Koryaks, Itelmens, and Eskimos at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, and to their own experience of ethnographic expeditions held in the 1980s–1990s.

In these descriptions, several stages of fly agaric intoxication are singled out with the third seemingly the most interesting —the stage where contact with anthropomorphic fly- agarics occurs. Here is how Bogoraz describes it: “Intoxicating fly-agarics, for example, represent ‘a special tribe.’ They are very strong, and when they grow, they are capable of breaking through the dense roots of trees with their strong caps cutting them into two. They grow through stones and crush them into small pieces. When fly-agarics make themselves seen to drunk people, they take strange humanoid forms. Once the fly-agaric, for example, took the form of a one-armed and one-legged person, in another incident, the mushroom looked like a stump. And those are not ghosts, these are fly-agarics, as such. Their number corresponds to the number of mushrooms a person eats. If a person ate one fly-agaric, only one mushroom would make itself seen then, if two or three were eaten, then two or three would be seen, accordingly. Taken by the hand by fly-agarics, people are accompanied to the other world, where they are shown everything—also the most incredible things are done with them. The paths fly agarics take are winding. They visit a country where the dead live."

Bogoraz also describes a drawing that illustrates a path that a person carried away by fly-agarics takes: “Such a person thinks he is a deer, then he ‘immerses’ and then returns again, overwhelmed by the same idea. In the picture, his path connects all the people and animals that he saw during his drunken sleep.”

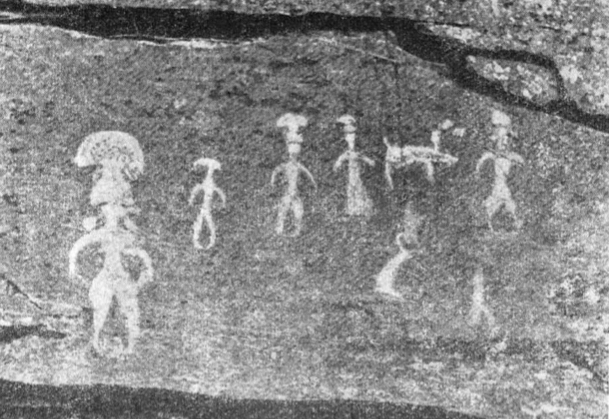

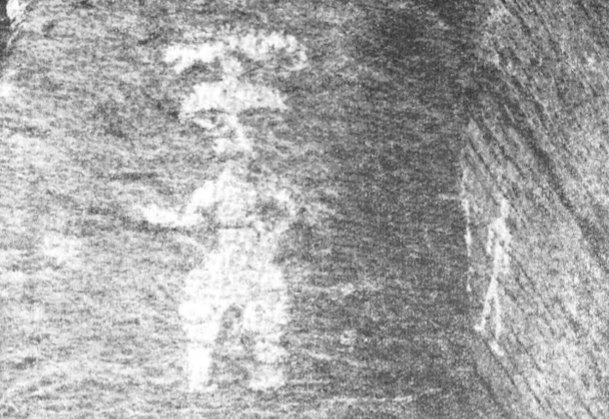

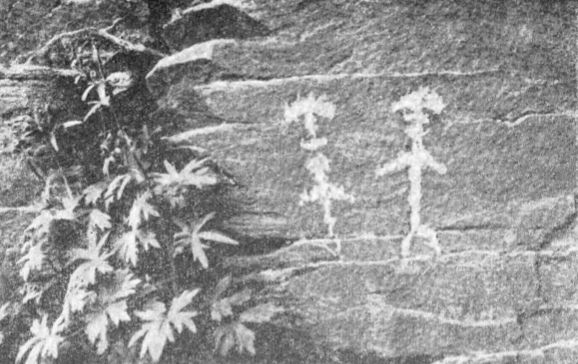

Another source of information about the fly-agaric people is the Pegtymel petroglyphs discovered in Chukotka in 1965. Their estimated age is between the 1st millennium BC to the 1st millennium AD, and the attention is drawn to scenes involving anthropomorphic figures with mushrooms on their heads (or replacing the heads). These figures, defined by researchers as representing fly-agaric people, are mostly female, as in the Itelmens’ tales.

Translated from Russian by Olga Bubich

Images from Nikolai Dikov's book Cave mysteries of ancient Chukotka. Petroglyphs of Pegtymel («Наскальные загадки древней Чукотки. Петроглифы Пегтымеля»), 1971